Gadabuursi

| Gadabuursi جادابورسي سمرون | |

|---|---|

| Dir Somali Clan | |

The Tomb of Sheikh Samaroon | |

| Ethnicity | Somali |

| Location | |

| Descended from | Gadabuursi |

| Parent tribe | Dir |

| Branches |

|

| Language | Somali Arabic |

| Religion | Islam (Sunni, Sufism) |

The Gadabuursi (Somali: Gadabuursi, Arabic: جادابورسي), also known as Samaroon (Arabic: قبيلة سَمَرُون), is a northern Somali clan, a sub-division of the Dir clan family.[1][2][3]

The Gadabuursi are geographically spread out across three countries: Ethiopia, Somaliland and Djibouti. Among all of the Gadabuursi inhabited regions of the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is the country where the majority of the clan reside. In Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi are mainly found in the Somali Region, but they also inhabit the Harar, Dire Dawa and Oromia regions.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

In Somaliland, the Gadabuursi are the predominant clan of the Awdal Region.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21] They are mainly found in cities and towns such as Borama, Baki, Lughaya, Zeila, Dilla, Jarahorato, Amud, Abasa, Fiqi Aadan, Quljeed, Boon and Harirad.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] In Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi are the predominant clan of the Awbare district in the Fafan Zone, the Dembel district in the Sitti Zone and the Harrawa Valley.[31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38] They are mainly found in cities and towns such as Awbare, Awbube, Sheder, Lefe Isa, Derwernache, Gogti, Jaare, Heregel, Arabi and Dembel.[31][39][33][40][41][42]

The etymology of the name Gadabuursi, as described by writer Ferrand in Ethnographic Survey of Africa refers to Gada meaning people and Bur meaning mountain, hence the etymology of the name Gadabuursi means people of the mountains.[43][44]

Overview

As a Dir sub-clan, the Gadabuursi have immediate lineal ties with the Issa, the Surre (Abdalle and Qubeys), the Biimaal (who the Gaadsen also belong to), the Bajimal, the Bursuk, the Madigan Dir, the Gurgura, the Garre (the Quranyow sub-clan to be precise as they claim descent from Dir), Gurre, Gariire, other Dir sub-clans and they have lineal ties with the Hawiye (Irir), Hawadle, Ajuran, Degoodi, Gaalje'el clan groups, who share the same ancestor Samaale.[45][46][47][2][48][49][50]

I. M. Lewis gives an invaluable reference to an Arabic manuscript on the history of the Gadabuursi Somali. 'This Chronicle opens', Lewis tells us, 'with an account of the wars of Imam 'Ali Si'id (d. 1392) from whom the Gadabuursi today trace their descent, and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the western flank in the armies of Se'ad ad-Din, ruler of Zeila:[51]

I. M. Lewis (1959) states:

"Further light on the Dir advance and Galla withdrawal seems to be afforded by an Arabic manuscript describing the history of the Gadabursi clan. This chronicle opens with an account of the wars of Imam 'Ali Si'id (d. 1392), from whom the Gadabursi today trace their descent and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the Western flank in the armies of Sa'd ad-Din (d. 1415), ruler of Zeila."[52]

The Gadabuursi are divided into two main divisions, the Habar Makadur and Habar 'Affan.[53][54] Most Gadabuursi members are descendants of Sheikh Samaroon. However, Samaroon does not necessarily mean Gadabuursi, but rather represents only a sub-clan of the Gadabuursi clan family.

The Gadabuursi in particular, is one of the clans with a longstanding institution of Sultan. The Gadabuursi use the title Ughaz or Ugaas which means sultan and/or king.[55][56]

Based on research done by the Eritrean author 'Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad' in his book 'The Saho of Eritrea, the Saho people (Gadafur) is said to have Somali origins from the Gadabuursi.[57]

Distribution

The Gadabuursi are mainly found in northwestern Somaliland and are the predominant clan of the Awdal Region.[58][14][15][16][59][18][19][60][21]

Federico Battera (2005) states about the Awdal Region:

"Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans."[61]

A UN Report published by Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (1999), states concerning Awdal:

"The Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs."[62]

Roland Marchal (1997) states that numerically, the Gadabuursi are the predominant inhabitants of the Awdal Region:

"The Gadabuursi's numerical predominance in Awdal virtually ensures that Gadabuursi interests drive the politics of the region."[63]

Marleen Renders and Ulf Terlinden (2010) both state that the Gadabuursi almost exclusively inhabit the Awdal Region:

"Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security."[64]

The Gadabuursi also partially inhabit the neighboring region of Maroodi Jeex, and reside in many cities within that province.[65][66] The Gadabuursi are the second largest clan by population in Somaliland after the Isaaq.[67][68][69] Within Somalia, they are known to be the 5th largest clan.[70]

The Gadabuursi are also found in Djibouti, where they are the second largest Somali clan.[71] Within Djibouti they have historically lived in 2 of the 7 major neighborhoods in Djibouti (Quarter 4 and 5).[72]

However the majority of the Gadabuursi inhabit Ethiopia.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81]

Federico Battera (2005) states:

"But most of the Gadabuursi inhabit the Somali Region of Ethiopia (the so-called region five) where their paramount chief (the Ugaas) resides...[82] In present day Awdal, most of the prominent elders have their main venues in the capital city of the region, Booroma. However, the paramount chief of the Gadabuursi local community, the Ugaas, has his main venue in Ethiopia."[83]

In Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi exclusively inhabit the Awbare district in the Fafan Zone, the Dembel district in the Sitti Zone and the Harrawa Valley.[84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91]

The Department of Sociology and Social Administration, Addis Ababa University, Vol. 1 (1994), describes the Awbare district as being predominantly Gadabuursi. The journal states:

"Different aid groups were also set up to help communities cope in the predominantly Gadabursi district of Aw Bare."[32]

Filipo Ambrosio (1994) describes the Awbare district as being predominantly Gadabuursi whilst highlighting the neutral role that they played in mediating peace between the Geri and Jarso:

"The Gadabursi, who dominate the adjacent Awbare district north of Jijiga and bordering with the Awdal Region of Somaliland, have opened the already existing camps of Derwanache and Teferi Ber to these two communities."[33]

Filipo Ambrosio (1994) highlights how the Geri and Jarso both sought refuge on adjacent Gadabuursi clan territory after a series of conflicts broke out between the two communities in the early 1990s:

"Jarso and Geri then sought refuge on 'neutral' adjacent Gadabursi territory in Heregel, Jarre and Lefeisa."[40]

The Research-inspired Policy and Practice Learning in Ethiopia and the Nile region (2010) states that the Dembel district is predominantly Gadabuursi:

"Mainly Somali Gurgura, Gadabursi and Hawiye groups, who inhabit Erer, Dambal and Meiso districts respectively."[34]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabuursi country, as within sight of Harar:

"In front, backed by the dark hills of Harar, lay the Harawwah valley."[92]

Captain H.G.C Swayne R.E. (1895) describes the Harrawa Valley as traditional Gadabuursi territory:

"On 5th September we descended into the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabursi country, and back on to the high ban again at Sarír, four days later. We then marched along the base of the Harar Highlands, reaching Sala Asseleh on 13th September. We had experienced heavy thunder-storms with deluges of rain daily, and had found the whole country deserted."[36]

Captain H.G.C Swayne R.E. (1895) describes the Harrawa Valley as occupying an important strategic position in the Gadabuursi country:

"The position of the Samawé ruins would favour a supposition that some power holding Harar, and having its northern boundary along the hills which wall in the southern side of the Harrawa valley, had built the fort to command the Gáwa Pass, which is one of the great routes from the Gadabursi country up on to the Marar Prairie."[37]

Richard Francis Burton describes the Gadabuursi as extending to within sight of Harar:

"Though almost in sight of Harar, our advance was impeded by the African traveller's bane. The Gudabursi tribe was at enmity with the Girhi, and, in such cases, the custom is for your friends to detain you and for their enemies to bar your progress. Shermarkay had given me a letter to the Gerad Adan, chief of the Girhi; a family feud between him and his brother-in-law, our Gudabursi protector, rendered the latter chary of commiting himself."[93]

The Gadabuursi, along with the Geri, Issa and Karanle Hawiye represent the most native and indigenous Somali tribes in Harar.[4][94][95][96]

The Gadabuursi inhabit the Gursum woreda where they are the majority and the Jijiga woreda where they make up a large part of the Fafan Zone. They partially inhabit Ayesha, Shinile, Erer and Afdem woreda's.[97][98][99]

The Gadabuursi also reside along the northeastern fringe of the chartered city-state of Dire Dawa, which borders the Dembel district, but also in the city itself.[100][9] The Gadabuursi are the second largest sub-clan within the borders of the Somali Region of Ethiopia based on the Ethiopian population census.[101] The 2014 Summary and Statistical report of the Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia has shown that Awbare is the most populated district in the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[101]

The Gadabuursi of Ethiopia have also expressed a desire to combine the clan's traditional territories to form a new region-state called Harawo Zone.[102]

Saho people

The Saho are an ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa.[103] They are principally concentrated in Eritrea, with some also living in adjacent parts of Ethiopia. They speak Saho, a Cushitic language which is related to Somali.[104]

Among the Saho there is a sub-clan called the Gadafur. The Gadafur are an independent sub-clan affiliated with the Minifere tribes and are believed to be originally from the tribe of Gadabuursi.[57]

History

Medieval Age

I. M. Lewis gives an invaluable reference to an Arabic manuscript on the history of the Gadabuursi Somali. 'This Chronicle opens', Lewis tells us, 'with an account of the wars of Imam 'Ali Si'id (d. 1392) from whom the Gadabuursi today trace their descent, and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the western flank in the armies of Se'ad ad-Din, ruler of Zeila.[51]

I. M. Lewis (1959) states:

"Further light on the Dir advance and Galla withdrawal seems to be afforded by an Arabic manuscript describing the history of the Gadabursi clan. This chronicle opens with an account of the wars of Imam 'Ali Si'id (d. 1392), from whom the Gadabursi today trace their descent and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the Western flank in the armies of Sa'd ad-Din (d. 1415), ruler of Zeila."[52]

I. M. Lewis (1959) also highlights that the Gadabuursi were in conflict with the Galla, during and after the campaigns against the Christian Abyssinians:

"These campaigns were clearly against the Christian Abyssinians, but it appears from the chronicle that the Gadabursi were also fighting the Galla. A later leader of the clan, Ugas 'Ali Makahil, who was born in 1575 at Dobo, north of the present town of Borama in the west of the British Protectorate, is recorded as having inflicted a heavy defeat on Galla forces at Nabadid, a village in the Protectorate."[105]

Sa'ad ad-Din II was the joint founder of the Kingdom of Adal along with his brother Haqq ad-Din II.[51] Not only did the Gadabuursi clan contribute to the Adal Wars and the Conquest of Abyssinia, but their predecessors were also fighting wars well before the establishment of the Adal Sultanate.[106] His descendants praise and sing his hymns and make their pilgrimages to his local shrine at Tukali to commemorate their ancestor. The largest portion of the Gadabuursi reside in Ethiopia.[107] According to traditional Gadabuursi history, a great battle took place between the Gadabuursi and the Galla in the 14th century at Waraf, a location near Hardo Galle in Ethiopia.[108] According to Max Planck, one branch of the Reer Ughaz family (Reer Ugaas) in Ethiopia rose to the rank of Dejazmach (Amharic: ደጃዝማች) or Commander of the Gate.[109] This was a military title meaning commander of the central body of a traditional Ethiopian armed force composed of a vanguard, main body, left and right wings and a rear body.[4]

Shihab al-Din Ahmad mentions the Habar Makadur by name in his famous book Futuh al Habasha. He states:

"Among the Somali tribes there was another called Habr Maqdi, from which the imam had demanded the alms tax. They refused to pay it, resorting to banditry on the roads, and acting evilly towards the country."[110]

Richard Pankhurst (2003) states that the Habr Maqdi are the Habar Makadur of the Gadabuursi.[111]

19th Century

All the trade routes linking Harar to the Somali coast passed through the Somali and Oromo territories where the Gadabuursi held a significant monopoly on the trade routes to the coast.

Wehib M. Ahmed (2015) mentions that the Gadabuursi dominated sections of the trade routes connecting Harar to Zeila in the History of Harar and the Hararis:

"In the 19th century the jurisdiction of the Amirs was limited to Harar and its close environs, while the whole trade routes to the coast passed through Oromo and the Somali territories. There were only two practicable routes: one was the Jaldeissa, through Somali Issa and Nole Oromo territories, the other of Darmy through the Gadaboursi. The Somali, who held a monopoly as transporters, took full advantage of the prevailing conditions and the merchants were the victim of all forms of abuse and extortion... Under the supervision of these agents the caravan would be entrusted to abbans (caravan protector), who usually belonged to the Issa or Gadaboursi when destined to the coast and to Jarso when destined for the interior."[112]

Elisée Reclus (1886) describes one of the ancient routes from Harar to Zeila ascending the Darmi Pass which crosses the heartland of the Gadabuursi country:

"Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on the point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep, and affords safe shelter to large craft."[27]

Philipp Paulitschke (1888) describes the perilous nature of the roads surrounding Zeila, frequently under pressure from Gadabuursi and Danakil raiders:

"The road via Tokosha, Hambôs and Abusuên was completely waterless at this time and therefore unusable. There was a general fear, rightly so, of the Danâkil, so much that the escort of a caravan couldn't have been persuaded to take this path. Danger also existed for the route we chose via Wárabot and Henssa, made unsafe by the Gadaburssi raiders, but is the one relatively more frequently committed."[113]

Philipp Paulitschke (1888) describes how the Wadi Aschat, a valley on the outskirts of Zeila, served as the headquarters of the Gadabuursi raiders:

"Starting immediately on the right bank of Wâdi Ashât, accompanying the narrow path through the Salsola bush 20-30 metre high hills at a distance of 5-6 km. The country shaft offers the appearance of a wavy, artificially created terrain covered with tall grass. Individuals come against the caravan path; others are lined up in groups and close due to the location. Here and there small cauldrons form which will soon come against the caravan route, heading west or east. They have been lurking in this area since ancient times, the Somâl terrain so suitable for raids, armed with lances, shield and knife, mostly on horseback, rarely on foot, and weaker caravans have to fight their way through force by force. The plunderers who have their headquarters here belong to the Gadaburssi tribe. There are also robbers from all the neighbouring areas. The attacks on the caravans are carried out on horseback, and the natives, on their nimble steeds, take such an excellent cover that they bring honour to every European rider."[114]

He also described the Wadi Aschat as having a legendary and nefarious reputation:

"We crossed, in the slowly rising terrain, the Wâdi Aschât, approximately 20m wide, a fairly deep cut trickle, which approached us in terrible sunshine from a southwesterly direction through the Salsola bushes adorned with a small hilly landscape. We already in Zeila were warned about this infamous site, from legend it is said, is soaked with the blood of the caravans."[115]

Eliakim Littel (1894) describes the remains of an Egyptian fortress built near Harar to protect the trade routes linking Harar to Zeila from the Gadabuursi:

On the east bank of the Dega-hardani are the remains of a fortress built by the Egyptians during their occupation of this country, of which I shall have more to say. The object of this wayside fort was to protect their trade from the plundering Gadabursi tribe, whose country at this place approaches the road.[116]

French Somaliland (Côte Française des Somalis)

The Gadabuursi were the pioneers of the name Côte Française des Somalis or the French Coast of the Somalis. Haji Dideh, the Sultan of Zeila, and prosperous merchant coined the name to the French. He also built the first mosque in Djibouti.[117][118][119] Before the French aligned with the Issa, the Gadabuursi held the position of the first Senator of the country and the first Somali head of state to lead French Somaliland, the territory compromising Djibouti today. Djama Ali Moussa, a former sailor, pursued his political aspirations and managed to become the first Somali democratically elected head of state in French Somaliland.[120][121] Prior to 1963, which coincided with the death of Djama Ali Moussa, political life in Djibouti was dominated by the Gadabuursi and Arab communities who were political allies and made up the majority of the inhabitants of the city of Djibouti.[122] After his death, the Afar and Issa rose to power.[122][123]

The Ambassadorial Brothers

The Ambassadorial Brothers were three brothers from a prominent family in the Horn of Africa.[124][125][126]

They were:

- Ismail Sheikh Hassan, served as Ethiopia's Ambassador to Libya.

- Aden Sheikh Hassan, served as Djibouti's Ambassador to Oman and Saudi Arabia.

- Mohamed Sheikh Hassan, served as Somalia's Ambassador to the United Arab Republic, Canada and Nigeria.

They were all sons of Sheikh Hassan Nuriye and from the Reer Ughaz (Reer Ugaas) subclan of the Makayl-Dheere section of the Gadabuursi.

Sheikh Hassan Nuriye in turn was a descendant of Ughaz Roble I. He was a famous sheikh and merchant in Somaliland, Ethiopia and Djibouti. He was based mainly in Ethiopia around Harar and Dire Dawa.

Eventually Sheikh Hassan Nuriye returned to his hometown of Teferi Ber (Awbare) and died there. He is buried in the town of Awbare next to Sheikh Awbare. His sons came to be known as The Ambassadorial Brothers. They were the first prominent family to have three individuals who are directly related to each other as brothers serving as ambassadors for three different neighboring countries.[124][125][126]

| Sheikh Hassan Nuriye | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohamed | Ismail | Aden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Three Somali brothers were citizens of three different countries, working in sensitive posts for three different governments.

Early Folk Music

The famous Austrian explorer and geographer, P. V. Paulitschke, mentioned that in 1886, the British General and Assistant Political Resident at Zeila, J. S. King, recorded a famous Somali folk song native to Zeila and titled: "To my Beloved", which was written by a Gadabuursi man to a girl of the same tribe. The song became hugely popular throughout Zeila despite it being incomprehensible to the other Somalis.

Philipp Paulitschke (1893) mentions about the song:

"To my Beloved: Ancient song of the Zeilans (Ahl Zeila), a mixture of Arabs, Somâli, Abyssinians and Negroes, which Major J. S. King dictated to a hundred-year-old man in 1886. The song was incomprehensible to the Somâl. It is undoubtedly written by a Gadaburssi and addressed to a girl of the same tribe."[127]

Lyrics of the song in Somali translated to English:

Inád dor santahâj wahân kagarân difta ku gutalah. |

Noticing your offbeat rhythm, likely from your heavy steps. |

| —To My Beloved[128] |

Balwo and Heello: Modern Somali Music

Modern Somali music began with the Balwo style, pioneered by Abdi Sinimo, who rose to fame in the early 1940s.[129][130][131] Abdi's innovation and passion for music revolutionized Somali music forever.[132] Its lyrical contents often deal with love, affection and passion. The Balwo genre was a forerunner to the Heello genre. Abdi Sinimo hailed from the North Western Regions of Somaliland and Djibouti, more precisely the Reer Nuur section of the Gadabuursi.[133][134][135] Modern sung Somali Poetry was introduced in the Heello genre which is a form of Somali sung poetry. The Balwo name changed to Heello because of religious reasons. The earliest composers began their songs with Balwooy, Balwooy hoy Balwooy... however because of the negative connotation connected to the Balwo and the word meaning calamity in Arabic, the Balwo was changed to Heello and thus the first bars of songs began with Heelloy, heellelloy.[136]

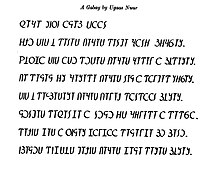

Below is a sample of a poem written Abdi Sinimo.[137]

Balwooy! Hoy balwooy |

Balwoy! O Balwoy |

| —Abdi Sinimo[138] |

Early Somali Cinema

Hassan Sheikh Mumin is considered among the greatest modern songwriters and playwrights in Greater Somalia and hailed from the Jibriil Yoonis subclan of the Gadabuursi.[139] He was born in 1931, in the port town of Zeila, in what was then British Somaliland. Because his father was a great sheikh, he received a classical Quranic and Arabic education. He also attended a government elementary school. He became a well-known collector and reciter of traditional oral literature, and composed his own texts, of which his most important work is Shabeelnaagood (1965), a piece that touches on the social position of women, urbanization, changing traditional practices, and the importance of education during the early pre-independence period. Although the issues it describes were later to some degree redressed, the work remains a mainstay of Somali literature.[140] Shabeelnaagood was translated into English in 1974 under the title Leopard Among the Women by the Somali Studies pioneer Bogumił W. Andrzejewski, who also wrote the introduction. Mumin composed both the play itself and the music used in it.[141] The piece is regularly featured in various school curricula, including Oxford University, which first published the English translation under its press house.

During one decisive passage in the play, the heroine, Shallaayo, laments that she has been tricked into a false marriage by the Leopard in the title:

"Women have no share in the encampments of this world

And it is men who made these laws, to their own advantage.

By God, by God, men are our enemies, though we ourselves nurtured them

We suckled them at our breasts, and they maimed us:

We do not share peace with them."[142]

Roble Afdeb (Rooble Afdeeb)

Roble Afdeb was a famous Somali warrior and poet from the North Western regions of Somaliland and Djibouti. Known to have pillaged and raided many Issa settlements. The poet and warrior is a legend in Somali history and was highly renowned for his bravery and gained fame not only through anti-colonialism and Islamic devotion but also clan rivalries.

Ali Bu'ul (Cali Bucul)

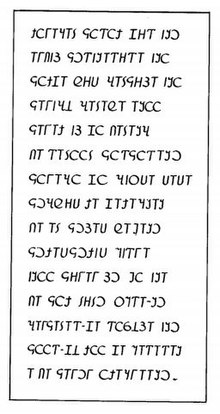

Ali Bu'ul was a famous Somali military leader and poet from the Western Somali regions, today within the borders of the Somali region of Ethiopia, known for his short lined poems (geeraar), compared to the long lines of gabay. Geeraar is traditionally recited on horseback during times of battle and war. Many of his most well known poems are still known today. He is also known to have battled the Somali religious leader named Mahamed Abdullah Hassan in poetry and coined the word Guulwade. Some of his famous works are Gammaan waa magac guud (Horse is a general term), Guulside (Victory-Bearer) and Amaan Faras (In Praise of My Horse). His poems were also written in the Gadabuursi Script. An extract of a geeraar, Amaan Faras, featured in the image below illustrates the work written in the script.[143][144][145][146]

The image above translates as:[147]

"From the seaside of Bulahar, to the corner of the Almis mountain, and Harawe of the pools, Hargeisa of the Gob trees, My horse reaches all that in one afternoon, Is it not like a scuddling cloud? From its pen, a huge roar is heard, Is it not like a lion leading a pride? In the open plains It makes the camels kneel down, Is it not like an expert camel-rustler? Its mane and tail has white tufts on the top, Is it not as beautiful as a galool tree abloom?"

— Ali Bu'ul (Cali Bucul), In Praise of My Horse

Geography

Alfred Pease (1897), who in the late 19th century visited the Gadabuursi country, describes it as the most beautiful tract of country he had visited in Somaliland:

"And we continued our journey northwards along the northern edge of the Bur'Maado and Simodi ranges to Aliman. We found all this country thickly inhabited by the Gadabursi, and here alone, in Northern Somaliland, we had the companionship for days together of a running stream. No part of Somaliland that I have visited is more beautiful than this tract of country, watered by an almost perennial stream, now lined with great trees festooned with the armo creeper, now with the high green elephant grass or luxuriant jungles, and guarded by woody and rocky mountains on the left hand and on the right. Between the Tug or Wady and these hills the, country had a park-like appearance, with its open glades and grassy plains. But the new and varied vegetation of Africa was not the only object delightful to the eye: countless varieties of birds, hawks, buzzards, Batteleur and larger eagles, vultures, dobie birds, golden orioles, parrots, paroquets, the exquisite Somali starlings, doves of all sorts and sizes, small and great honey-birds, hoopoes, jays, green pigeons, great flocks of Guinea fowl, partridges, sand grouse, were ever to be seen on every hand, and, while the bush teemed with Waller's gazelle and dik-diks, the plains with Scemmerring's antelope, with a sprinkling of oryx, our road up the Tug was constantly crossed by the tracks of lions, elephants, leopards, the ubiquitous hyaena, and other wild beasts."[148]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes the flora and fauna of the Harrawa Valley in his book First Footsteps in East Africa:

"For six hours we rode the breadth of the Harawwah Valley: it was covered with wild vegetation, and surface-drains, that carry off the surplus of the hills enclosing it. In some places the torrent beds had cut twenty feet into the soil. The banks were fringed with milk-bush and Asclepias, the Armo-creeper, a variety of thorns, and especially the yellow-berried Jujube: here numberless birds followed bright-winged butterflies, and the "Shaykhs of the Blind," as the people call the black fly, settled in swarms upon our hands and faces as we rode by. The higher ground was overgrown with a kind of cactus, which here becomes a tree, forming shady avenues. Its quadrangular fleshy branches of emerald green, sometimes forty feet high, support upon their summits large round bunches of a bright crimson berry: when the plantation is close, domes of extreme beauty appear scattered over the surface of the country... At Zayla I had been informed that elephants are "thick as sand" in Harawwah: even the Gudabirsi, when at a distance, declared that they fed there like sheep, and, after our failure, swore that they killed thirty but last year."[149]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes what he feels is the end of his journey when he witnesses the blue hills of Harar, which is the iconic backdrop of the Harrawa Valley in his book First Footsteps in East Africa:

"Beyond it stretched the Wady Harawwah, a long gloomy hollow in the general level. The background was a bold sweep of blue hill, the second gradient of the Harar line, and on its summit closing the western horizon lay a golden streak—the Marar Prairie. Already I felt at the end of my journey."[150]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes the Abasa Valley in the Gadabuursi country as amongst the most beautiful spots he has seen:

"At half past three reloading we followed the course of the Abbaso Valley, the most beautiful spot we had yet seen. The presence of mankind, however, was denoted by the cut branches of thorn encumbering the bed: we remarked too, the tracks of lions pursued by hunters, and the frequent streaks of serpents, sometimes five inches in diameter."[151]

In 1885, Frank Linsly James describes Captain Stewart King's visit to the famous Eilo Mountain in the Gadabuursi country in the Lughaya District where the Gadabuursi natives informed him of the remains of ancient cities:

"The natives had told him that in the hill called Ailo about three days' march south-east from Zeila, there were remains of ancient cities, and substantially built houses... He hoped to be able to visit them. The whole country south-east of Zeila, inhabited by the Gadabursi tribe, had never yet been explored by a European. There was also in the hill Ailo a celebrated cave, which had been described to him as having a small entrance about three feet from the ground in the face of the limestone cliff. He had spoken to two or three men who had been inside it. They stated that they climbed up and entered with difficulty through the small opening; they then went down some steps and found themselves in an immense cave with a stream of water running through it, but pitch dark. A story was told of a Somali who once went into the cave and lost his way. In order to guide him out the people lighted fires outside, and he came out and told most extraordinary tales, stating that he found a race of men there who never left the cave, but had flocks and herds."[152]

In 1886 the British General and Assistant Political Resident at Zeila, J. S. King, travelling by the coastal strip near Khor Kulangarit, near Laan Cawaale in the Lughaya District, passed by the famous tomb of 'Sharmarke of the White Shield', a famous Gadabuursi leader, poet, elder and grandfather of the current Sultan of the Bahabar Musa, Abshir Du'ale who was inaugurated in 2011 in the town of Lughaya:

"Shortly after passing the bed of the large river, called Barregid we halted for half an hour at a place where there were several large hollows like dried-up lakes, but I was informed that the rain-water does not remain in them any time. Close by, on a piece of rising ground, was a small cemetery enclosed by a circular fence of cut bushes. Most conspicuous among the graves was that of Sharmãrké, Gãshân 'Ada (Sharmãrké of the White Shield), a celebrated elder of the Bah Habr Músa section of the Gadabúrsi, who died about 20 years ago. The grave was surrounded by slabs of beautiful lithographic limestone brought from Eilo, and covered with sea shells brought from the coast, distant at least 10 miles."[153]

In 1887, French poet and traveller, Arthur Rimbaud, visited the coastal plains of British Somaliland where he described the region between Zeila and Bulhar as part of the Gadabuursi country, with the clan centred around Sabawanaag in present day Lughaya District:

“Zeila, Berbera, and Bulhar remain in English hands, as well as the Bay of Samawanak, along the Gadiboursi coast, between Zeila and Bulhar, the place where the last French consular agent in Zeila, M. Henry, had planted the tricolor, the Gadiboursi tribe themselves having requested our protection, which is always enjoyed. All these stories of annexation or protection have been stirring up the minds along this coast these last two years.”[154]

Gadabuursi Ughazate (Ugaasyada ama Boqortooyada Gadabuursi)

The royal family of the Gadabuursi, the Ughazate, evolved from and is a successor kingdom to the Adal Sultanate and Sultanate of Harar.[155] The first Ughaz (Ugaas) of this successor kingdom, Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere) was the son of Makail Dera, the progenitor of the Makayl-Dheere.[156] During the late 19th century, as the region became subject to colonial rule, the Ughaz assumed a more traditional and ceremonial leadership of the clan.[156]

The Gadabuursi give their King the title of Ughaz.[157] It's an authentic Somali term for King or Sultan. The Gadabuursi in particular are one of the clans with a long tradition of the institution of Sultan.[55]

History

The first Ughaz of the Gadabuursi was Ughaz Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere), who is the progenitor of the Reer Ughaz (Reer Ugaas) subclan to which the royal lineage belongs.

Ughaz Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere) who was born in 1575 in Dobo, an area north of the present town of Borama in north-western Somaliland, is recorded as having inflicted a heavy defeat on Galla forces at Nabadid.[105]

I. M. Lewis (1959) highlights that the Gadabuursi were in conflict with the Galla during the reign of Ughaz Ali Makail Dera, during and after the campaigns against the Christian Abyssinians:

"These campaigns were clearly against the Christian Abyssinians, but it appears from the chronicle that the Gadabursi were also fighting the Galla. A later leader of the clan, Ugas 'Ali Makahil, who was born in 1575 at Dobo, north of the present town of Borama in the west of the British Protectorate, is recorded as having inflicted a heavy defeat on Galla forces at Nabadid, a village in the Protectorate."[105]

Ughaz Nur I, who was crowned in 1698, married Faaya Aale Boore who was the daughter of a famous Oromo King and Chief, Aale Boore.[156] Ughaz Nur I and Faaya Aale Boore gave birth to Ughaz Hiraab and Ughaz Shirdoon, who later became the 6th and 7th Ughaz respectively.[156] Aale Boore was a famous Oromo King, the victory of the former over the latter marked a historical turning point in concluding the Oromo predominance in the Eastern Hararghe region.[156]

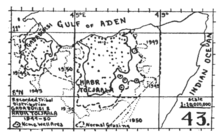

The Gadabuursi managed to defeat and kill the next Oromo King after Aale Boore during the reign of Ughaz Roble I who was crowned in 1817. It is said that during his reign the Gadabuursi tribe reached great influence and tremendous height in the region, having managed to defeat the reigning Galla/Oromo King at that time whose name was Nuuno which struck a blow to the Galla's morale, due to their much loved King being killed. He was defeated by Geedi Bahdoon, also known as Geedi Malable. He struck a spear right through the King while he was in front of a tree, the spear pierced inside the tree making it not able for the King to escape or remove the spear. After he died he was buried in an area that's now called Qabri Nuuno near Sheedheer. In the picture already shared titled 'An old map featuring the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabuursi country, north of Harar' one can read Gabri Nono, which is the anglicized version of the Somali Qabri Nuuno.[156][1]

Ughaz Roble I died in 1848 and was buried in an area called Dhehror (Dhexroor) in the Harrawa Valley. It has become the custom for Somalis after Ughaz Roble I that whenever an Ughaz gets inaugurated and it rains, he should be named Ughaz Roble, which translates to 'the one with rain' or 'rainmaker'.

Ughaz Nur II was born in Zeila in the year 1835 and crowned in Bagi in 1848. In his youth, he loved riding, hunting and the traditional arts and memorized a great number of proverbs, stories and poems.[158]

Eventually, Ughaz Nur II created his own store of sayings, poems and stories that are quoted to this day. He knew by heart the Gadabuursi heer (customary law) and amended or added new heer during his reign. He was known for fair dealing to friend and stranger alike. It is said that he was the first Gadabuursi Ughaz to introduce guards and askaris armed with arrows and bows.[159]

During the rule of Ughaz Nur II both Egypt and Ethiopia were contending for power and supremacy in the Horn of Africa. The European colonial powers were also competing for strategic territories and ports in the Horn of Africa.[159]

In the year 1876, Egypt using Islam as a bargaining chip signed a treaty with Ughaz Nur II and came to occupy the Northern Somali coast which included Zeila.[159] But the Egyptians also occupied the town of Harar and the Harar-Zeila-Berbera caravan route.

On 25 March 1885, the French government claimed that they signed a treaty with Ughaz Nur II of the Gadabuursi placing much of the coast and interior of the Gadabuursi country under the protectorate of France. The treaty titled in French, Traitè de Protectorat sur les Territoires du pays des Gada-Boursis, was signed by both J. Henry, the Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harar-Zeila, and Nur Robleh, Ughaz of the Gadabuursi, at Zeila on 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885). The treaty states as follows (translated from French):

"Between the undersigned J. Henry, Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harrar-Zeilah, and Nour Roblé, Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, independent sovereign of the whole country of the Gada-boursis, and to safeguard the interests of the latter who is asking for the protectorate of France,

It was agreed as follows:

Art. 1st – The territories belonging to Ougasse Nour-Roblé of the Gada-boursis from "Arawa" to "Hélo" from "Hélô" to Lebah-lé", from "Lebah-lé" to "Coulongarèta" extreme limit by Zeilah, are placed directly under the protection of France.

Art. 2 – The French government will have the option of opening one or more commercial ports on the coast belonging to the territory of the Gada-boursis.

Art. 3 The French government will have the option of establishing customs in the posts open to trade, and on the points of the borders of the territory of the Gada-boursis where it deems it necessary. Customs tariffs will be set by the French government, and the revenues will be applied to public services.

Art. 4 – Regulations for the administration of the country will be elaborated later by the French government. In agreement with the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis they will always be revisable at the will of the French government, a French resident may be established on the territory of the Gada-boursis to sanction by his presence the protectorate of France.

Art. 5 – The troops and the police of the country will be raised among the natives, and will be placed under the superior command of an officer designated by the French government. Arms and ammunition for the native troops may be provided by the French government and their balance taken from the public revenues, but, in case of insufficiency, the French government may provide for them.

Art. 6 – The Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, to recognize the good practices of France towards it, undertakes to protect the caravan routes and mainly to protect French trade, throughout the extent of its territory.

Art. 7 – The Ougasse of the Gada-boursis undertakes not to make any treaty with any other power, without the assistance and consent of the French government.

Art. 8 – A monthly allowance will be paid to the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis by the French government, this allowance will be fixed later, by a special convention, after the ratification of this treaty by the French government.

Art. 9 – This treaty was made voluntarily and signed by the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, which undertakes to execute it faithfully and to adopt the French flag as its flag.

In witness whereof the undersigned have affixed their stamps and signatures.

J.Henry

Signature of Ougasse

Done at Zeilah on 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885)."

— Traité de protectorat de la France sur les territoires du pays des Gada-boursis, 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885), Zeilah.[160]

The French claimed that the treaty with the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi gave them jurisdiction over the entirety of the Zeila coast and the Gadabuursi country.[161]

However, the British attempted to deny this agreement between the French and the Gadabuursi citing that that Ughaz had a representative at Zeila when the Gadabuursi signed their treaty with the British in December 1884. The British suspected that this treaty was designed by the Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harrar-Zeila to circumvent British jurisdiction over the Gadabuursi country and allow France to lay claim to sections of the Somali coast. There was also suspicion that Ughaz Nur II had attempted to cause a diplomatic row between the British and French governments in order to consolidate his own power in the region.[161]

According to I. M. Lewis, this treaty clearly influenced the demarcation of the boundaries between the two protectorates, establishing the coastal town of Djibouti as the future official capital of the French colony:

"By the end of 1885 Britain was preparing to resist an expected French landing at Zeila. Instead, however, of a decision by force, both sides now agreed to negotiate. The result was an Anglo-French agreement of 1888 which defined the boundaries of the two protectorates as between Zeila and Jibuti: four years later the latter port became the official capital of the French colony."[162]

Fall of Harar in 1887

Ughaz Nur II went to Egypt and met Isma'il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt, who honored him with medals and expensive gifts. The Ughaz there signed a treaty accepting Egyptian protection of Muslims in Somaliland and Ethiopia.[163] According to I. M. Lewis, he was also gifted with firearms amongst other weapons.[164] In 1884, two years after Britain took over Egypt, Britain also occupied Egyptian territories, especially the northern Somali coast. However Ughaz Nur II had little to do with the British, as long as they did not interfere with his rule, the customs of his people, and their trade routes.[163] Ughaz Nur II had established strong relations with the Emir of Harar, Abdallah II ibn Ali. In 1887, when Harar was occupied by Menelik II of Ethiopia, Ughaz Nur II sent Gadabuursi askaris to support Abdallah II ibn Ali[159] and in another historical account, he himself participated in the battle.[158] Harar officially fell to Menelik in 1887.[165]

Ughaz Nur II recited lines of poetry lamenting the fall of Harar to Menelik in 1887:

Tolkayow xalay taah ma ladin toosna maan qabine |

My people, last night my moans did not leave me yet no ailment plagued me. |

| —Ughaz Nur II (Ugaas Nuur) Tolkayow[158] |

Ughaz Nur II was at first in a distinct and advantageous position, for not only did the caravan route to Harar run through Gadabuursi clan territory, but the Gadabuursi at the time were partly cultivating and so easier to control and tax. Yet for this very reason, after the 1897 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, Ughaz Nur II, a far-sighted man, did everything in his power to prevent his people cultivating, for he realised that it would bring them under the control of the Amharic authority established at Harar.[166] Colonel Stace (1893) mentioned that the Abyssinians were encroaching further into the Gadabuursi homeland near Harar:

"The Abyssinians from Harar are encroaching more and more upon the Gadabursi country, as I anticipated would be the result of their unopposed occupation of Biyo Kaboba. I fear that they will make a permanent settlement in the Harrawa Valley from whence the encroachments and exactions will extend further into the Protectorate."[167]

Ras Makonnen sent a letter to Colonel E. V. Stace complaining that the Gadabuursi have begun attacking all caravans coming into Harar and denied any plans to militarily attack the Gadabuursi:

"From - RAS MAKUNAN, Amir of Harrar and its Dependencies,

To COLONEL E. V. STACE, Political Agent and Consul, Somali Coast...

As for the Gadabursi, they are always molesting and looting the travellers who come to Harrar. This we do not hide from you. The doings of this tribe are much injurious and troublesome to all the people as they loot the travellers without cause. As regards what you wrote appertaining to an intended attack by some of our soldiers against them (Gadabursi), we are not aware of it because we were absent. Before taking such steps, we would consult you."[168]

Ras Makonnen, the newly appointed Ethiopian governor of Harar, offered the Gadabuursi protection in exchange for collaboration. Ughaz Nur II refused and fought Ethiopian expansion until he died in 1898. Ughaz Nur II is buried in Dirri.[159]

His work was and is still taught in Somali Poetry classes (Suugaan: Fasalka Koobaad) among other Somali poets. His poems were also written in the Gadabuursi Script.[169][158]

For more about Ughaz Nur II, visit the following:

The image above translates as:[170]

"Oh God! How often have I made a man hostile to me sleep in the front part of the house. How often have I allowed a man against whom my flesh turned to continue speaking. I am not hasty in dispute, how often have I shown forbearance. How often have I given a second helping of honey to the man who only waited to hurt me. When I turn the sewing machine and scatter the seeds of treachery (or trickery). The trap which I have prepared for him (my enemy) when he sets his chest on top of it. How often have I caught him unawares."

— Ughaz Nur II (Ugaas Nuur), Dissimulation

Translation of another variation of the poem by B. W. Andrzejewski (1993):[171]

"If any man intended aught of villainy against me, by God, how snug I made my forecourt for his bed-mat, none the less! And if, with aggression in his thoughts, He pastured his horses to get them battle-fit, How in spite of this I made him griddle-cakes of maize to eat! Amiably I conversed with him for whom my body felt revulsion. I did not hurry, I was patient in dealing with his tricks. I showed a relaxed and easy mien, My looks gave no grounds for suspicion in his mind. Lips open, words betraying nothing of deceit, smiles, Laughter on the surface, not rising from the gullet's depth. In our game of shax I would make this move and that, And say, "This seems to be the one that's more to my advantage." I offered banter and engaged in well-turned talk, All the while setting a trap for him, Ready for the day when he would show his real intentions. I would flood him with deceit, while I arranged my plan of action. Then, when he was all unknowing and unwarned, O how I struck him down!"

— Ughaz Nur II (Ugaas Nuur), Dissimulation

Philipp Paulitschke (1893) mentioned a poem which became extremely popular in the Gadabuursi country called Imminent loss of the Prince. This poem became very popular when the Gadabuursi heard that the British intended to supplant the traditional line of Ughaz Nur II towards the end of his life and appoint a more favourable Ughaz, 'Elmi Warfa:

Ninkî donî-rarestaj, |

A man in charge of ships, |

| —Imminent loss of the Prince[172] |

Philipp Paulitschke (1893) comments on the above poem:

"This poem is an example of the improvisational art of the Somâl, Somâl girls were singing in the interior of the Gadaburssi country when it became known that Ugâs Nûr Roble, the old prince of the land, was imprisoned in Zeila and a great statesman of the tribe, Elmi Worfa appointed Ugâs of the Gadaburssi-Somâl by the British government."[173]

Major R. G. Edwards Leckie writes about his meeting with Ughaz Nur II in his A Visit to the Gadabuursi:

"We were warned that he did not love the Feringi (white man), and therefore thought it better to send a messenger ahead to His Majesty and return with a confidential report on the situation."[174]

Major R. G. Edwards Leckie also writes about his appearance:

"This old man was Ugaz Nur, King or Sultan of the Gadabursi. He had several other names which I do not remember now... Ugaz Nur was about seventy five years old. Although stiffened by age, he was tall, straight and well built. Even the weight of his many years could not alter the chief's graceful figure... His dress was simple and lacked the usual Oriental splendour. Many of his subjects were attired much more gaily, but none looked more distinguished. He wore a crinkly white tobe, with the end of which he covered his head, forming a hood. Over this he wore a cloak of black cloth lined with crimson silk, probably a present from the Emperor of Abyssinia. In his hand he carried a simple staff instead of the regulation shield and spear. His fighting days were over, and he now relied upon his stalwart sons to protect him on his journeys. As he shook hands with us he smiled pleasantly. His manner was composed and dignified, evidently inherited from his ancestors, who were rulers in the country for many generations."[175]

Ughaz Roble II was the 12th in line of the Gadabuursi Ughazate. Based mainly in Harar, he was crowned the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi after his father's (Ughaz Nur II) death.[158] His position as Ughaz proved to be quite controversial amongst the Gadabuursi due to his close relationship with the Ethiopian ruling dynasty.[176] He would go on to receive payments, gifts and weapons from the British, the French and the Abyssinians who were all vying for the region.[158] He eventually fell out of favor with the British and became close allies with Menelik II who officially recognized him as the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi.[159]

When Lij Iyasu came to power in Abyssinia he cemented a close relationship with Ughaz Roble II and gave him a close female relative from the Ethiopian royal household in marriage.[177][178][158]

The Arab Bureau, which was a collection of British intelligence officers headquartered in Cairo and charged with the task of coordinating imperial intelligence activities, recorded this event in the Arab Bureau Summaries Volumes 1–114 (1986), where it also mentioned that the British deposed Ughaz Roble II from power due to his alliance with the Ethiopian establishment:

"Lij Yasu has, however, given a female relative of his in marriage to the late Agaz of the Gadabursi, who was recently deposed by us for his intrigues and misgovernment."[177]

Andrew Caplan (1971) records Lij Iyasu wanting to enter into an alliance with the Gadabuursi, in his book British policy towards Ethiopia 1909–1919:

"The Prince (Lij Iyasu) was also negotiating for an alliance with the Gadabursi Somali... He had given one of his relatives to its Ex-Ughaz Robleh Nur."[178]

After the deposition of his ally Lij Iyasu by Empress Zewditu, Ughaz Roble II witnessed the October 1916 massacre of the inhabitants of Harar by Abyssinian soldiers and was given immunity along with some of the other prominent leaders in the region. This event marked a turning point in the relations between the Somalis and the ruling Abyssinians in the region. Ughaz Roble II was given special immunity because of his high profile and personal relations with those in the Ethiopian royal family to whom he was also related by virtue of marriage.[176][158] Ughaz Roble II was considered a very controversial figure and was the first Gadabuursi Ughaz to have been deposed by his own people.[158][159] The deposition from position of Ughaz caused a huge stir amongst the Gadabuursi.[159] Ughaz Roble II was known to love hunting, archery, horse riding and he inherited a rifle that was given as a gift to his father Ughaz Nur II by the Khedive of Egypt, Isma'il Pasha.[158] He died in 1938 and was buried in Awbare, which became the seat of the Ughazate of the Gadabuursi in the early 20th century.[158]

Ughaz 'Elmi Warfa was the 13th in line of the Gadabuursi Ughazate. His other names were 'Ilmi-Dheere ('Elmi the Tall) and Kun 'Iil (A Thousand Sorrows).[159]

In the late 1890s, the British appointed 'Elmi Warfa Ughaz of all the Gadabuursi in the British Protectorate. Ughaz 'Elmi thus supplanted the traditional line of Ughaz Nur II and his successor, Ughaz Roble II, who had fallen out of favor with the British.[159] Ughaz 'Elmi's authority was recognized in an installation ceremony in 1917 in Zeila. However the traditional successor of Ughaz Nur II, Ughaz Robleh II, remained the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi in Ethiopia.[159] Ughaz 'Elmi was a member of the delegation that had accompanied Ughaz Nur II to Egypt in the late 1870s and also was one of the Gadabuursi elders who signed the treaty with the British at Zeila in 1884.[159]

Ughaz 'Elmi's usurpation of the traditional Gadabuursi line of succession provoked other sub-clans and caused a lot of controversy. Many sub-clans, especially the rer Yunus or the Yunus branch felt it was their turn to vie for the Ughaz-ship. This sparked a conflict which was also conducted in poetic duels. These poems were rich imagery and symbolism. Two of the best are "Dhega Taag" (A Battle-Cry) by 'Elmi the Tall or 'Elmi Dheire' and the other called "Aabudle" (A Declaration of Faith) by Farid Dabi-Hay,[159] who was one of Ughaz 'Elmi's rivals.

For more about Ughaz 'Elmi Warfaa, visit the following:

Ughaz Dodi (Daudi) Ughaz Roble II, was crowned Ughaz of the Gadabuursi in Ethiopia in the late 1940s. Before he became Ughaz, he was appointed Dejazmach (Commander of the Gate) by the Ethiopian authorities.[109] He was a source of constant problems for the British Protectorate and was accused of conspiring with Italian forces during World War II.[158] After the war, British soldiers were sent to arrest him and he was eventually taken into custody whilst in Jijiga by the British and forcibly exiled to the Karaman Island in Yemen where he was imprisoned for 7 years.[179][158] He was accompanied by his family in his forced exile. Ultimately he was released and when he returned to the British Protectorate he was immediately detained again on Saad-ud-Din Island, within the British governor's jurisdiction.[179] The Gadabuursi recognized him as their Ughaz in a grand meeting of Gadabuursi notables in Ethiopia. After his return from forced exile, the Ethiopian government sent him a delegation informing him that Haile Selassie recognizes him as the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi in Ethiopia.[158] Despite this, during the end of his life Ughaz Dodi refused to recognize Ethiopian rule and returned the Ethiopian delegation that was sent to him. In 1948, Ughaz Dodi along with Sultan Hassan of the Jidwaq, signed a document called 'Petition for Amalgamation from the Jigjiga area, with the other Somali territories.' This document was primarily signed in order to petition the Four Power Commission of Investigation for the Former Italian Colonies (1948) to end Ethiopian occupation of Somali territories, return all Somali territories held by the Ethiopians and unify the territories under a United Somaliland.[180] It was soon after this that he died in 1949.[158]

Administration

The Gadabuursi Kingdom was established more than 600 years ago and consisted of a King (Ugaas) and many elders.

Hundreds of elders used to work in four sections consisting of 25 elders each:

- Social committee

- Defense – policing authorities consisting of horsemen (referred to as fardoolay), foot soldiers and spear-men, but also askaris or soldiers equipped with poison arrows.[181]

- Economy and collection of taxes

- Justice committee

The chairmen of the four sections were called Afarta Dhadhaar, and were selected according to talent and personal abilities.

A constitution, Xeer Gadabuursi, had been developed, which divided every case as to whether it was new or had precedents (ugub or curad).

The Gadabuursi King and the elders opposed the arrival of the British at the turn of the 20th century, but they ended up signing an agreement with them. Later, as disagreements between the two parties arose and intensified, the British installed a friendly Ugaas against the recognized traditional Ugaas in hopes of overthrowing him. This would eventually bring about the collapse of the kingdom.[159]

Customary Law (Xeer)

The Law of the King and the 100 Men (Xeerka Boqorka iyo Boqolka Nin)

When a new Ughaz (Ugaas) was appointed amongst the Gadabuursi, a hundred elders, representatives of all the lineages of the clan, assembled to form a parliament to promulgate new Xeer agreements, and to decide which legislation they wished to retain from the reign of the previous Ugaas. The compensation rates for delicts committed within the clan were revised if necessary, and a corpus of Gadabuursi law, as it were, was placed on the statutes for the duration of the new Ugaas's rule.

This was called 'The Law of the King and the 100 men' (Xeerka Boqorka iyo Boqolka Nin).[182]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes the Gadabuursi Ugaas as hosting equestrian games for 100 men in the Harrawa Valley, also known as the Harar Valley or Wady Harawwah, a long running valley situated in the Gadabuursi country, north of Harar, Ethiopia. He states:

"Here, probably to commemorate the westward progress of the tribe, the Gudabirsi Ugaz or chief has the white canvass turban bound about his brows, and hence rides forth to witness the equestrian games in the Harawwah Valley."[183]

Traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony

Here is a summary of a very full account of the traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony mentioned by I. M. Lewis (1999) in A Pastoral Democracy:

"The pastoral Somali have few large ceremonies and little ritual. For its interest, therefore I reproduce here a summary of a very full account of the traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony given me by Sheikh 'Abdarahmaan Sheikh Nuur, the present Government Kadi of Borama. Clansmen gather for the ceremony in a well-wooded and watered place. There is singing and dancing, then stock are slaughtered for feasting and sacrifice. The stars are carefully watched to determine a propitious time, and then future Ugaas is chosen by divination. Candidates must be sons or brothers of the former Ugaas and the issue of a woman who has been only married once. She should not be a woman who has been divorced or a widow. Early on a Monday morning a man of the Reer Nuur (the laandeer of the Gadabuursi) plucks a flower or leaf and throws it upon the Ugaas. Everyone else then follows his example. The man who starts the `aleemasaar acclamation must be a man rich in livestock, with four wives, and many sons. Men of the Mahad Muuse lineage then brings four vessels of milk. One contains camels' milk, one cows' milk, one sheeps' milk, and the last goats' milk. These are offered to the Ugaas who selects one and drinks a little from it. If he drinks the camels' milk, camels will be blessed and prosper, if he drinks, the goats' milk, goats will prosper, and so on. After this, a large four-year-old ram is slaughtered in front of him. His hair is cut by a man of the Gadabuursi and he casts off his old clothes and dons new clothes as Ugaas. A man of Reer Yuunis puts a white turban round his head, and his old clothes are carried off by men of the Jibra'iin... The Ugaas then mounts his best horse and rides to a well called Bugay, near Geris, towards the coast. The well contains deliciously fresh water. Above the well are white pebbles and on these he sits. He is washed by a brother or other close kinsman as he sits on top of the stones. Then he returns to the assembled people and is again acclaimed and crowned with leaves. Dancing and feasting recommence. The Ugaas makes a speech in which he blesses his people and asks God to grant peace, abundant milk, and rain—all symbols of peace and prosperity (nabad iyo 'aano). If rain falls after this, people will know that his reign will be prosperous. That the ceremony is customarily performed during the karan rainy season makes this all the more likely. The Ugaas is given a new house with entirely new effects and furnishings and a bride is sought for him. She must be of good family, and the child of a woman who has had only one husband. Her bride-wealth is paid by all the Gadabuursi collectively, as they thus ensure for themselves successors to the title. Rifles or other fire-arms are not included in the bride-wealth. Everything connected with the accession must be peaceful and propitious."[184]

Leaders

| Name | Reign

From |

Reign

Till |

Born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ughaz Ali Makail Dera | 1607 | 1639 | 1575[185] |

| 2 | Ughaz Abdi I Ughaz Ali Makail Dera | 1639 | 1664 | |

| 3 | Ughaz Husein Ughaz Abdi Ughaz Ali | 1664 | 1665 | |

| 4 | Ughaz Abdillah Ughaz Abdi I Ughaz Ali | 1665 | 1698 | |

| 5 | Ughaz Nur I Ughaz Abdi I Ughaz Ali | 1698 | 1733 | |

| 6 | Ughaz Hirab Ughaz Nur I Ughaz Abdi I | 1733 | 1750 | |

| 7 | Ughaz Shirdon Ughaz Nur I Ughaz Abdi I | 1750 | 1772 | |

| 8 | Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon Ughaz Nur I | 1772 | 1812 | |

| 9 | Ughaz Guleid Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon | 1812 | 1817 | |

| 10 | Ughaz Roble I Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon | 1817 | 1848 | |

| 11 | Ughaz Nur II Ughaz Roble I Ughaz Samatar | 1848 | 1898 | 1835 |

| 12 | Ughaz Roble II Ughaz Nur II Ughaz Roble I | 1898 | 1938 | |

| 13 | Ughaz Elmi Warfa Ughaz Roble I | 1917 | 1935 | 1835[186] or 1853[158] |

| 14 | Ughaz Abdi II Ughaz Roble Ughaz Nur II | 1938 | 1941 | |

| 15 | Ughaz Dodi Ughaz Roble Ughaz Nur | 1948 | 1949 | |

| 16 | Ughaz Roble III Ughaz Dodi Ughaz Roble | 1952 | 1977 | |

| 17 | Ughaz Jama Muhumed Ughaz'Elmi-Warfa | 1960 | 1985 | |

| 18 | Ughaz Abdirashid Ughaz Roble III Ughaz Dodi | 1985 | -[187] |

Currently Abdirashid Ughaz Roble III Ughaz Dodi is the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi.[158]

Y-DNA

DNA analysis of Dir clan members inhabiting Djibouti found that all of the individuals belonged to the Y-DNA Haplogroup T-M184.[188] The Gadabuursi belong to the T-M184 paternal haplogroup and the TMRCA is estimated to be 2100–2200 years or 150 BCE.[189][190][191] A notable member of the T-M184 is the third US president, Thomas Jefferson.[192]

Clan tree

The Gadabuursi are divided into two main divisions, the Habar Makadur and Habar 'Affan.[53][54]

The Habar Makadur and Habar 'Affan, both historically united under a common Sultan or Ughaz.[45][193][194]

- Gadabuursi

- Habar Makadur

- Mahad 'Ase

- Bahabar Abokor

- Bahabar Muse

- Habr Musa

- Bahabar Aden

- Bababar 'Eli

- Reer Mohamed

- Abrahim (Abrayn)

- Makahil

- 'Eli

- 'Iye

- 'Abdalle (Bahabar 'Abdalle)

- Hassan (Bahabar Hassan)

- Muse

- Makail Dera (Makayl-Dheere)

- Afgudud (Gibril Muse)

- Bah Sanayo

- Younis (Reer Yoonis)

- 'Ali Younis

- Jibril Younis (Jibriil Yoonis)

- Adan Younis (Aadan Yoonis)

- Nur Younis (Reer Nuur)

- Mahad 'Ase

- Habar 'Affan

- Jibrain

- Ali Ganun

- Gobe

- Habar Yusif

- Reer Issa

- Hebjire

- Reer Zuber

- Dhega Wayne

- Makayl

- Musa

- Musafin

- Hassan Sá'ad

- Farole

- Reer Hamud

- Musa

- Habar Makadur

The following listing is taken from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001.[195][196]

- Dir

Notable figures

- Aden Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Djibouti, one of the three Ambassadorial Brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Mohamed Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Somalia, one of the three Ambassadorial Brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Ismail Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Ethiopia, one of the three Ambassadorial Brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Ali Bu'ul, famous Somali poet from the 19th century, known for his geeraar's (short styled Somali poems recited during battles and wars).

- Roble Afdeb, famous legendary Somali warrior and poet, remembered for his bravery and clan-rivalry.

- Mohamed Farah Abdullahi (Hansharo), leader of Somali Democratic Alliance (f. 1989).

- Aden Isaq Ahmed, Minister and Politician of the Somali Republic.

- Col. Muse Rabile Ghod, a Somali military leader and statesman of the Somali Democratic Republic.

- Yuusuf Talan, General of the Somali National Army.

- Abdi Buuni, Minister under the British Somaliland Protectorate and First Deputy Prime Minister of the Somali Republic.

- Djama Ali Moussa, First Senator of Djibouti or French Somaliland.

- Hon. Ato Hussein Ismail, Ethiopian long-serving Statesman and first Somali to become a member of the Ethiopian Parliament.

- Hon. Ato Kemal Hashi Mohamoud, Ethiopian politician serving as Member of the House of Peoples' Representatives of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and Member of the House's Advisory Committee.[197]

- Saharla Abdulahi Bahdon, Ethiopian politician serving as Member of the House of People's Representatives of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and first Somali to ever represent Addis Ababa as a Member of the House of People's Representatives.[198]

- Abdirahman Aw Ali Farrah, first Somaliland Vice President, 1993–1997.[199]

- Mawlid Hayir, former vice-president and minister of education and former governor of the Fafan Zone in the Somali region of Ethiopia.[200][201]

- Haji Ibrahim Nur, minister, merchant and politician of former British Somaliland Protectorate.

- Hibo Nuura, Somali singer.

- Abdi Hassan Buni, politician, minister of British Somaliland and first deputy prime minister of the Somali Republic.

- Abdi Ismail Samatar, Somali scholar, writer and professor.

- Ahmed Ismail Samatar, Somali writer, professor and former dean of the Institute for Global Citizenship at Macalester College. Editor of Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies.

- Abdirahman Beyle, former Foreign Affairs Minister of Somalia an economist.[202]

- Abdisalam Omer, Foreign Affairs Minister of Somalia and former Governor of the Central Bank of Somalia.[203]

- Sheikh 'Abdurahman Sh. Nur, religious leader, qādi and the inventor of the Borama script.[204]

- Dahir Rayale Kahin, third President of Somaliland.

- Ahmed Gerri of the Habar Makadur of the Conquest of Abyssinia.[53][54]

- Sultan Dideh, sultan of Zeila, prosperous merchant and built first mosque in Djibouti. He also proposed the name "Cote francaise des Somalis" to the French.[71][205]

- Yussur Abrar, former governor of the Central Bank of Somalia.[206]

- Ughaz Nur II, 11th Malak (King) of the Gadabuursi.[207]

- Ughaz 'Elmi Warfa, 13th Malak (King) of the Gadabuursi.

- Hon. Ato Shemsedin Ahmed, Somali Ethiopian Politician, previous Ethiopian ambassador to Djibouti, Kenya, Deputy Minister of Mining and Energy and first Vice Chairman and one of the founders of ESDL.[208][209]

- Ayanle Souleiman, Djiboutian athlete.

- Hassan Mead, American distance runner and 2016 Olympic Men's 5000m finalist.

- Abdirahman Sayli'i, current vice-president of Somaliland.[210]

- Ahmed Mumin Seed, Somaliland politician.

- Abdi Sinimo, a Somali singer and songwriter, noted for having established the balwo genre of Somali music.

- Hassan Sheikh Mumin, author of Shabeel Naagood or (Leopard among the Women) and composed the song Samo ku waar, which became the national anthem of the Republic of Somaliland.[211]

- Khadija Qalanjo, a popular Somali singer.

- Suleiman Ahmed Guleid, President of Amoud University.

- Omar Osman Rabe, Somali scholar, writer, professor, politician and pan-Somalist.

- Barkhad Awale Adan, Somali journalist and director of Radio Hurma.

References

- ^ a b I. M. Lewis (1959) "The Galla in Northern Somaliland" (PDF).

- ^ a b Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 9781135751753.

- ^ Verdier, Isabelle (31 May 1997). Ethiopia: the top 100 people. Indigo Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9782905760128.

- ^ a b Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

and thence strikes south-westwards among the Gudabirsi and Girhi Somal, who extend within sight of Harar.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (2000). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society (PDF). The Red Sea Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781569021033.

Including the land round Harar and Dire Dawa inhabited by the Somalis of the 'Iise and Gadabuursi clans.

- ^ Negatu, Workneh; Research, Addis Ababa University Institute of Development; Center, University of Wisconsin—Madison Land Tenure; Foundation, Ford (1 January 2004). Proceedings of the Workshop on Some Aspects of Rural Land Tenure in Ethiopia: Access, Use, and Transfer. IDR/AAU. p. 43.

Page:43 : Somali Settlers, Gadabursi, Issa

- ^ Gebre, Ayalew (2004). "When Pastoral Commons are privatised: Resource Deprivation and Changes in Land Tenure Systems among the Karrayu in the Upper Awash Valley Region of Ethiopia" (PDF).

- ^ Morin, Didier (1995). Des paroles douces comme la soie: introduction aux contes dans l'aire couchitique (Bedja, Afar, Saho, Somali) (in French). Peeters Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 9789068316780.

The Gadabursi reside in Funyan Bira with the Oromo.

- ^ a b Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 100. ISBN 9781569021033.

- ^ Dostal, Walter; Kraus, Wolfgang (22 April 2005). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 9780857716774.

- ^ "Somalia: The Myth of Clan-Based Statehood". Somalia Watch. 7 December 2002. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ Ambroso, G (2002). Pastoral society and transnational refugees:population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 (PDF). p. 5.

Main sub-clan(s) Habr Awal, Region(s): Waqooyi Galbeed, Main districts: Gabiley, Hargeisa, Berbera. Main sub-clan(s) Gadabursi, Region(s): Awdal, Main districts: Borama, Baki, part. Gabiley, Zeila, Lughaya.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link). - ^ a b Samatar, Abdi I. (4 November 2008). "Somali Reconstruction and Local Initiative: Amoud University". Bildhaan. 1 (1): 132.

Samaroon or Gadabursi is the clan name for the majority of people of Awdal origin.

- ^ a b Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans. The Gadaabursi are concentrated in Awdal.

- ^ a b UN (1999) Somaliland: Update to SML26165.E of 14 February 1997 on the situation in Zeila, including who is controlling it, whether there is fighting in the area, and whether refugees are returning. "Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs." p. 5.

- ^ Renders, Marleen; Terlinden, Ulf. "Chapter 9: Negotiating Statehood in a Hybrid Political Order: The Case of Somaliland". In Tobias Hagmann; Didier Péclard (eds.). Negotiating Statehood: Dynamics of Power and Domination in Africa (PDF). p. 191. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security.

- ^ a b Jörg, J (8 March 2024). What are Somalia's Development Perspectives?. Verlag Hans Schiler. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-86093-230-8.

Awdal region , populated by Dir clans : the Gadabursi and ` Cisa , is credited as being the most stable region in Somaliland . This is mainly due to peacekeeping efforts on the part of the Gadabursi clan who dominate this region.

- ^ a b Countries That Aren't Really Countries. p. 22.

The Isaaq are concentrated primarily in the regions of Maroodi Jeex, Sanaag, Gabiley, Togdheer and Saaxil. The Gadabuursi inhabit the west, pre-dominantly in Awdal, the Zeila district of Salal and parts of Gabiley.

- ^ Bruchhaus, E. M, Sommer, M. M. (8 March 2024). Hot Spot Horn of Africa Revisited (2008). p. 54. ISBN 978-3-8258-1314-7.

Next to the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi, a small minority of Ciisse inhabits Awdal.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Deutsches Institut für Afrika-Forschung (8 March 2024). Afrika Spectrum Volume 43. p. 77.

Gadabursi being the major descent group in the Awdal region.

- ^ Ciabarri, Luca. Dopo lo Stato. Storia e antropologia della ricomposizione sociale nella Somalia settentrionale: Storia e antropologia della ricomposizione sociale nella Somalia settentrionale (in Italian). FrancoAngeli. p. 258.

Baki region, the traditional region of the Gadabursi

- ^ Ambroso, Guido (August 2002). Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia. UNHCR Brussels.

Chart showing the Gadabursi exclusively inhabiting the Baki district

- ^ "An Ecological Assessment of the Coastal Plains of North Western Somalia (Somaliland)" (PDF). 2000. p. 11.

In the centre of the study area are the Gadabursi, who extend from the coastal plains around Lughaye, through the Baki and Borama districts into the Ethiopian highlands west of Jijiga.

- ^ "RUIN AND RENEWAL: THE STORY OF SOMALILAND". 2004.

So too is the boundary of Lughaya district whose predominant (if not exclusive) inhabitants are today Gadabursi.

- ^ Glawion, Tim (30 January 2020). The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65983-3.

Three distinct circles can be distinguished based on the way the security arena is composed in and around Zeila: first, Zeila town, the administrative centre, which is home to many government institutions and where the mostly ethnic Gadabuursi/Samaron inhabitants engage in trading or government service activities; second, Tokhoshi, an artisanal salt mining area eight kilometres west of Zeila, where a mixture of clan and state institutions provide security and two large ethnic groups (Ciise and Gadabuursi/Samaron) live alongside one another; third the southern rural areas, which are almost universally inhabited by the Ciise clan, with its long, rigid culture of self-rule.

- ^ a b Reclus, Elisée (1886). The Earth and its Inhabitants The Universal Geography Vol. X. North-east Africa (PDF). J.S. Virtue & Co, Limited, 294 City Road.

Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on a point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep, and affords safe shelter to large craft.

- ^ Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

The major town of the Rer Mohamoud Nur, Dila.

- ^ Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

The Gadabuursi Reer Mahammad Nuur, for example, are said to have begun cultivating in 1911 at Jara Horoto to the east of the present town of Borama.

- ^ Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- ^ a b Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

- ^ a b "Sociology Ethnology Bulletin of Addis Ababa University". 1994.

Different aid groups were also set up to help communities cope in the predominantly Gadabursi district of Aw Bare.

- ^ a b c "Theoretical and Practical Conflict Rehabilitation in the Somali Region of Ethiopia" (PDF). 2018–2019. p. 8.