g-force

The g-force or gravitational force equivalent is a mass-specific force (force per unit mass), expressed in units of standard gravity (symbol g or g0, not to be confused with "g", the symbol for grams). It is used for sustained accelerations, that cause a perception of weight. For example, an object at rest on Earth's surface is subject to 1 g, equaling the conventional value of gravitational acceleration on Earth, about 9.8 m/s2.[1] More transient acceleration, accompanied with significant jerk, is called shock.[citation needed]

When the g-force is produced by the surface of one object being pushed by the surface of another object, the reaction force to this push produces an equal and opposite force for every unit of each object's mass. The types of forces involved are transmitted through objects by interior mechanical stresses. Gravitational acceleration is one cause of an object's acceleration in relation to free fall.[2][3]

The g-force experienced by an object is due to the vector sum of all gravitational and non-gravitational forces acting on an object's freedom to move. In practice, as noted, these are surface-contact forces between objects. Such forces cause stresses and strains on objects, since they must be transmitted from an object surface. Because of these strains, large g-forces may be destructive.

For example, a force of 1 g on an object sitting on the Earth's surface is caused by the mechanical force exerted in the upward direction by the ground, keeping the object from going into free fall. The upward contact force from the ground ensures that an object at rest on the Earth's surface is accelerating relative to the free-fall condition. (Free fall is the path that the object would follow when falling freely toward the Earth's center). Stress inside the object is ensured from the fact that the ground contact forces are transmitted only from the point of contact with the ground.

Objects allowed to free-fall in an inertial trajectory, under the influence of gravitation only, feel no g-force – a condition known as weightlessness. Being in free fall in an inertial trajectory is colloquially called "zero-g", which is short for "zero g-force". Zero g-force conditions would occur inside an elevator falling freely toward the Earth's center (in vacuum), or (to good approximation) inside a spacecraft in Earth orbit. These are examples of coordinate acceleration (a change in velocity) without a sensation of weight.

In the absence of gravitational fields, or in directions at right angles to them, proper and coordinate accelerations are the same, and any coordinate acceleration must be produced by a corresponding g-force acceleration. An example of this is a rocket in free space: when the engines produce simple changes in velocity, those changes cause g-forces on the rocket and the passengers.

Unit and measurement

The unit of measure of acceleration in the International System of Units (SI) is m/s2.[4] However, to distinguish acceleration relative to free fall from simple acceleration (rate of change of velocity), the unit g is often used. One g is the force per unit mass due to gravity at the Earth's surface and is the standard gravity (symbol: gn), defined as 9.80665 metres per second squared,[5] or equivalently 9.80665 newtons of force per kilogram of mass. The unit definition does not vary with location—the g-force when standing on the Moon is almost exactly 1⁄6 that on Earth. The unit g is not one of the SI units, which uses "g" for gram. Also, "g" should not be confused with "G", which is the standard symbol for the gravitational constant.[6] This notation is commonly used in aviation, especially in aerobatic or combat military aviation, to describe the increased forces that must be overcome by pilots in order to remain conscious and not g-LOC (g-induced loss of consciousness).[7]

Measurement of g-force is typically achieved using an accelerometer (see discussion below in section #Measurement using an accelerometer). In certain cases, g-forces may be measured using suitably calibrated scales.

Acceleration and forces

The term g-"force" is technically incorrect as it is a measure of acceleration, not force. While acceleration is a vector quantity, g-force accelerations ("g-forces" for short) are often expressed as a scalar, based on the vector magnitude, with positive g-forces pointing downward (indicating upward acceleration), and negative g-forces pointing upward. Thus, a g-force is a vector of acceleration. It is an acceleration that must be produced by a mechanical force, and cannot be produced by simple gravitation. Objects acted upon only by gravitation experience (or "feel") no g-force, and are weightless. g-forces, when multiplied by a mass upon which they act, are associated with a certain type of mechanical force in the correct sense of the term "force", and this force produces compressive stress and tensile stress. Such forces result in the operational sensation of weight, but the equation carries a sign change due to the definition of positive weight in the direction downward, so the direction of weight-force is opposite to the direction of g-force acceleration:

- Weight = mass × −g-force

The reason for the minus sign is that the actual force (i.e., measured weight) on an object produced by a g-force is in the opposite direction to the sign of the g-force, since in physics, weight is not the force that produces the acceleration, but rather the equal-and-opposite reaction force to it. If the direction upward is taken as positive (the normal cartesian convention) then positive g-force (an acceleration vector that points upward) produces a force/weight on any mass, that acts downward (an example is positive-g acceleration of a rocket launch, producing downward weight). In the same way, a negative-g force is an acceleration vector downward (the negative direction on the y axis), and this acceleration downward produces a weight-force in a direction upward (thus pulling a pilot upward out of the seat, and forcing blood toward the head of a normally oriented pilot).

If a g-force (acceleration) is vertically upward and is applied by the ground (which is accelerating through space-time) or applied by the floor of an elevator to a standing person, most of the body experiences compressive stress which at any height, if multiplied by the area, is the related mechanical force, which is the product of the g-force and the supported mass (the mass above the level of support, including arms hanging down from above that level). At the same time, the arms themselves experience a tensile stress, which at any height, if multiplied by the area, is again the related mechanical force, which is the product of the g-force and the mass hanging below the point of mechanical support. The mechanical resistive force spreads from points of contact with the floor or supporting structure, and gradually decreases toward zero at the unsupported ends (the top in the case of support from below, such as a seat or the floor, the bottom for a hanging part of the body or object). With compressive force counted as negative tensile force, the rate of change of the tensile force in the direction of the g-force, per unit mass (the change between parts of the object such that the slice of the object between them has unit mass), is equal to the g-force plus the non-gravitational external forces on the slice, if any (counted positive in the direction opposite to the g-force).

For a given g-force the stresses are the same, regardless of whether this g-force is caused by mechanical resistance to gravity, or by a coordinate-acceleration (change in velocity) caused by a mechanical force, or by a combination of these. Hence, for people all mechanical forces feels exactly the same whether they cause coordinate acceleration or not. For objects likewise, the question of whether they can withstand the mechanical g-force without damage is the same for any type of g-force. For example, upward acceleration (e.g., increase of speed when going up or decrease of speed when going down) on Earth feels the same as being stationary on a celestial body with a higher surface gravity. Gravitation acting alone does not produce any g-force; g-force is only produced from mechanical pushes and pulls. For a free body (one that is free to move in space) such g-forces only arise as the "inertial" path that is the natural effect of gravitation, or the natural effect of the inertia of mass, is modified. Such modification may only arise from influences other than gravitation.

Examples of important situations involving g-forces include:

- The g-force acting on a stationary object resting on the Earth's surface is 1 g (upwards) and results from the resisting reaction of the Earth's surface bearing upwards equal to an acceleration of 1 g, and is equal and opposite to gravity. The number 1 is approximate, depending on location.

- The g-force acting on an object in any weightless environment such as free-fall in a vacuum is 0 g.

- The g-force acting on an object under acceleration can be much greater than 1 g, for example, the dragster pictured at top right can exert a horizontal g-force of 5.3 when accelerating.

- The g-force acting on an object under acceleration may be downwards, for example when cresting a sharp hill on a roller coaster.

- If there are no other external forces than gravity, the g-force in a rocket is the thrust per unit mass. Its magnitude is equal to the thrust-to-weight ratio times g, and to the consumption of delta-v per unit time.

- In the case of a shock, e.g., a collision, the g-force can be very large during a short time.

A classic example of negative g-force is in a fully inverted roller coaster which is accelerating (changing velocity) toward the ground. In this case, the roller coaster riders are accelerated toward the ground faster than gravity would accelerate them, and are thus pinned upside down in their seats. In this case, the mechanical force exerted by the seat causes the g-force by altering the path of the passenger downward in a way that differs from gravitational acceleration. The difference in downward motion, now faster than gravity would provide, is caused by the push of the seat, and it results in a g-force toward the ground.

All "coordinate accelerations" (or lack of them), are described by Newton's laws of motion as follows:

The Second Law of Motion, the law of acceleration, states that F = ma, meaning that a force F acting on a body is equal to the mass m of the body times its acceleration a.

The Third Law of Motion, the law of reciprocal actions, states that all forces occur in pairs, and these two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Newton's third law of motion means that not only does gravity behave as a force acting downwards on, say, a rock held in your hand but also that the rock exerts a force on the Earth, equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

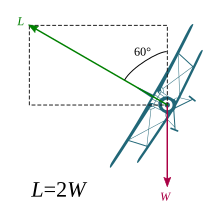

In an airplane, the pilot's seat can be thought of as the hand holding the rock, the pilot as the rock. When flying straight and level at 1 g, the pilot is acted upon by the force of gravity. His weight (a downward force) is 725 newtons (163 lbf). In accordance with Newton's third law, the plane and the seat underneath the pilot provides an equal and opposite force pushing upwards with a force of 725 N. This mechanical force provides the 1.0 g upward proper acceleration on the pilot, even though this velocity in the upward direction does not change (this is similar to the situation of a person standing on the ground, where the ground provides this force and this g-force).

If the pilot were suddenly to pull back on the stick and make his plane accelerate upwards at 9.8 m/s2, the total g‑force on his body is 2 g, half of which comes from the seat pushing the pilot to resist gravity, and half from the seat pushing the pilot to cause his upward acceleration—a change in velocity which also is a proper acceleration because it also differs from a free fall trajectory. Considered in the frame of reference of the plane his body is now generating a force of 1,450 N (330 lbf) downwards into his seat and the seat is simultaneously pushing upwards with an equal force of 1450 N.

Unopposed acceleration due to mechanical forces, and consequentially g-force, is experienced whenever anyone rides in a vehicle because it always causes a proper acceleration, and (in the absence of gravity) also always a coordinate acceleration (where velocity changes). Whenever the vehicle changes either direction or speed, the occupants feel lateral (side to side) or longitudinal (forward and backwards) forces produced by the mechanical push of their seats.

The expression "1 g = 9.80665 m/s2" means that for every second that elapses, velocity changes 9.80665 metres per second (35.30394 km/h). This rate of change in velocity can also be denoted as 9.80665 (metres per second) per second, or 9.80665 m/s2. For example: An acceleration of 1 g equates to a rate of change in velocity of approximately 35 km/h (22 mph) for each second that elapses. Therefore, if an automobile is capable of braking at 1 g and is traveling at 35 km/h, it can brake to a standstill in one second and the driver will experience a deceleration of 1 g. The automobile traveling at three times this speed, 105 km/h (65 mph), can brake to a standstill in three seconds.

In the case of an increase in speed from 0 to v with constant acceleration within a distance of s this acceleration is v2/(2s).

Preparing an object for g-tolerance (not getting damaged when subjected to a high g-force) is called g-hardening.[citation needed] This may apply to, e.g., instruments in a projectile shot by a gun.

Human tolerance

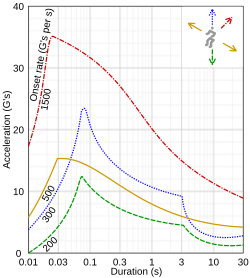

Human tolerances depend on the magnitude of the gravitational force, the length of time it is applied, the direction it acts, the location of application, and the posture of the body.[9][10]: 350

The human body is flexible and deformable, particularly the softer tissues. A hard slap on the face may briefly impose hundreds of g locally but not produce any real damage; a constant 16 g for a minute, however, may be deadly. When vibration is experienced, relatively low peak g-force levels can be severely damaging if they are at the resonant frequency of organs or connective tissues.[citation needed]

To some degree, g-tolerance can be trainable, and there is also considerable variation in innate ability between individuals. In addition, some illnesses, particularly cardiovascular problems, reduce g-tolerance.

Vertical

Aircraft pilots (in particular) sustain g-forces along the axis aligned with the spine. This causes significant variation in blood pressure along the length of the subject's body, which limits the maximum g-forces that can be tolerated.

Positive, or "upward" g-force, drives blood downward to the feet of a seated or standing person (more naturally, the feet and body may be seen as being driven by the upward force of the floor and seat, upward around the blood). Resistance to positive g-force varies. A typical person can handle about 5 g0 (49 m/s2) (meaning some people might pass out when riding a higher-g roller coaster, which in some cases exceeds this point) before losing consciousness, but through the combination of special g-suits and efforts to strain muscles—both of which act to force blood back into the brain—modern pilots can typically handle a sustained 9 g0 (88 m/s2) (see High-G training).

In aircraft particularly, vertical g-forces are often positive (force blood towards the feet and away from the head); this causes problems with the eyes and brain in particular. As positive vertical g-force is progressively increased (such as in a centrifuge) the following symptoms may be experienced:[citation needed]

- Grey-out, where the vision loses hue, easily reversible on levelling out

- Tunnel vision, where peripheral vision is progressively lost

- Blackout, a loss of vision while consciousness is maintained, caused by a lack of blood flow to the head

- G-LOC, a g-force induced loss of consciousness[11]

- Death, if g-forces are not quickly reduced

Resistance to "negative" or "downward" g, which drives blood to the head, is much lower. This limit is typically in the −2 to −3 g0 (−20 to −29 m/s2) range. This condition is sometimes referred to as red out where vision is literally reddened[12] due to the blood-laden lower eyelid being pulled into the field of vision.[13] Negative g-force is generally unpleasant and can cause damage. Blood vessels in the eyes or brain may swell or burst under the increased blood pressure, resulting in degraded sight or even blindness.

Horizontal

The human body is better at surviving g-forces that are perpendicular to the spine. In general when the acceleration is forwards (subject essentially lying on their back, colloquially known as "eyeballs in"),[14] a much higher tolerance is shown than when the acceleration is backwards (lying on their front, "eyeballs out") since blood vessels in the retina appear more sensitive in the latter direction.[citation needed]

Early experiments showed that untrained humans were able to tolerate a range of accelerations depending on the time of exposure. This ranged from as much as 20 g0 for less than 10 seconds, to 10 g0 for 1 minute, and 6 g0 for 10 minutes for both eyeballs in and out.[15] These forces were endured with cognitive facilities intact, as subjects were able to perform simple physical and communication tasks. The tests were determined not to cause long- or short-term harm although tolerance was quite subjective, with only the most motivated non-pilots capable of completing tests.[16] The record for peak experimental horizontal g-force tolerance is held by acceleration pioneer John Stapp, in a series of rocket sled deceleration experiments culminating in a late 1954 test in which he was clocked in a little over a second from a land speed of Mach 0.9. He survived a peak "eyeballs-out" acceleration of 46.2 times the acceleration of gravity, and more than 25 g0 for 1.1 seconds, proving that the human body is capable of this. Stapp lived another 45 years to age 89[17] without any ill effects.[18]

The highest recorded g-force experienced by a human who survived was during the 2003 IndyCar Series finale at Texas Motor Speedway on 12 October 2003, in the 2003 Chevy 500 when the car driven by Kenny Bräck made wheel-to-wheel contact with Tomas Scheckter's car. This immediately resulted in Bräck's car impacting the catch fence that would record a peak of 214 g0.[19][20]

Short duration shock, impact, and jerk

Impact and mechanical shock are usually used to describe a high-kinetic-energy, short-term excitation. A shock pulse is often measured by its peak acceleration in ɡ0·s and the pulse duration. Vibration is a periodic oscillation which can also be measured in ɡ0·s as well as frequency. The dynamics of these phenomena are what distinguish them from the g-forces caused by a relatively longer-term accelerations.[citation needed]

After a free fall from a height followed by deceleration over a distance during an impact, the shock on an object is · ɡ0. For example, a stiff and compact object dropped from 1 m that impacts over a distance of 1 mm is subjected to a 1000 ɡ0 deceleration.[citation needed]

Jerk is the rate of change of acceleration. In SI units, jerk is expressed as m/s3; it can also be expressed in standard gravity per second (ɡ0/s; 1 ɡ0/s ≈ 9.81 m/s3).[citation needed]

Other biological responses

Recent research carried out on extremophiles in Japan involved a variety of bacteria (including E. coli as a non-extremophile control) being subject to conditions of extreme gravity. The bacteria were cultivated while being rotated in an ultracentrifuge at high speeds corresponding to 403,627 g. Paracoccus denitrificans was one of the bacteria that displayed not only survival but also robust cellular growth under these conditions of hyperacceleration, which are usually only to be found in cosmic environments, such as on very massive stars or in the shock waves of supernovas. Analysis showed that the small size of prokaryotic cells is essential for successful growth under hypergravity. Notably, two multicellular species, the nematodes Panagrolaimus superbus[21] and Caenorhabditis elegans were shown to be able to tolerate 400,000 × g for 1 hour.[22] The research has implications on the feasibility of panspermia.[23][24]

Typical examples

| Example | g-force[a] |

|---|---|

| The gyro rotors in Gravity Probe B and the free-floating proof masses in the TRIAD I navigation satellite[25] | 0 g |

| A ride in the Vomit Comet (parabolic flight) | ≈ 0 g |

| Standing on Mimas, the smallest and least massive known body rounded by its own gravity | 0.006 g |

| Standing on Ceres, the smallest and least massive known body currently in hydrostatic equilibrium | 0.029 g |

| Standing on Pluto at average ground level | 0.063 g |

| Standing on Eris at average ground level | 0.084 g |

| Standing on Titan at average ground level | 0.138 g |

| Standing on Ganymede at average surface level | 0.146 g |

| Standing on the Moon at surface level | 0.1657 g |

| 2000 Toyota Sienna from 0 to 100 km/h in 9.2 s[26] | 0.3075–0.314 g |

| Standing on Mercury | 0.377 g |

| Standing on Mars at its equator at mean ground level | 0.378 g |

| Standing on Venus at average ground level | 0.905 g |

| Standing on Earth at sea level–standard | 1 g |

| Saturn V Moon rocket just after launch and the gravity of Neptune where atmospheric pressure is about Earth's | 1.14 g |

| Bugatti Veyron from 0 to 100 km/h in 2.4 s | 1.55 g[b] |

| Gravitron amusement ride | 2.5–3 g |

| Gravity of Jupiter at its mid-latitudes and where atmospheric pressure is about Earth's | 2.528 g |

| Uninhibited sneeze after sniffing ground pepper[27] | 2.9 g |

| Space Shuttle, maximum during launch and reentry | 3 g |

| High-g roller coasters[10]: 340 | 3.5–12 g |

| Hearty greeting slap on upper back[27] | 4.1 g |

| Top Fuel drag racing world record of 4.4 s over 1/4 mile | 4.2 g |

| First world war aircraft (ex:Sopwith Camel, Fokker Dr.1, SPAD S.XIII, Nieuport 17, Albatros D.III) in dogfight maneuvering. | 4.5–7 g |

| Luge, maximum expected at the Whistler Sliding Centre | 5.2 g |

| Formula One car, maximum under heavy braking[28] | 6.3 g |

| Tower Of Terror, highest g-force steel rollercoaster | 6.3 g |

| Formula One car, peak lateral in turns[29] | 6–6.5 g |

| Standard, full aerobatics certified glider | +7/−5 g |

| Apollo 16 on reentry[30] | 7.19 g |

| Maximum permitted g-force in Sukhoi Su-27 plane | 9 g |

| Maximum permitted g-force in Mikoyan MiG-35 plane and maximum permitted g-force turn in Red Bull Air Race planes | 10 g |

| Flip Flap Railway, highest g-force wooden rollercoaster | 12 g |

| Jet Fighter pilot during ejection seat activation | 15–25 g |

| Gravitational acceleration at the surface of the Sun | 28 g |

| Maximum g-force in Tor missile system[31] | 30 g |

| Maximum for human on a rocket sled | 46.2 g |

| Formula One 2021 British Grand Prix Max Verstappen Crash with Lewis Hamilton | 51 g |

| Formula One 2020 Bahrain Grand Prix Romain Grosjean Crash[32] | 67 g |

| Sprint missile | 100 g |

| Brief human exposure survived in crash[33] | > 100 g |

| IndyCar 2003 Texas Kenny Bräck Crash | 214 g |

| Formula One 2014 Japanese Grand Prix Jules Bianchi Crash | 254 g |

| Formula One 1994 Monaco Grand Prix Karl Wendlinger[34] Crash | ≈360 g |

| Coronal mass ejection (Sun)[35] | 480 g |

| Formula One 1994 San Marino Grand Prix Roland Ratzenberger Qualifying Crash | 500 g |

| Space gun with a barrel length of 1 km and a muzzle velocity of 6 km/s, as proposed by Quicklaunch (assuming constant acceleration) | 1,800 g |

| Shock capability of mechanical wrist watches[36] | > 5,000 g |

| V8 Formula One engine, maximum piston acceleration[37] | 8,600 g |

| Mantis Shrimp, acceleration of claw during predatory strike[38] | 10,400 g |

| Rating of electronics built into military artillery shells[39] | 15,500 g |

| Analytical ultracentrifuge spinning at 60,000 rpm, at the bottom of the analysis cell (7.2 cm)[40] | 300,000 g |

| Calculated acceleration of the mandibles of the ant species Mystrium camillae[41] | 607,805 g |

| Acceleration of a nematocyst: the fastest recorded acceleration from any biological entity.[42] | 5,410,000 g |

| Mean acceleration of a proton in the Large Hadron Collider[43] | 190,000,000 g |

| Gravitational acceleration at the surface of a typical neutron star[44] | 2.0×1011 g |

| Acceleration from a wakefield plasma accelerator[45] | 8.9×1020 g |

Measurement using an accelerometer

An accelerometer, in its simplest form, is a damped mass on the end of a spring, with some way of measuring how far the mass has moved on the spring in a particular direction, called an 'axis'.

Accelerometers are often calibrated to measure g-force along one or more axes. If a stationary, single-axis accelerometer is oriented so that its measuring axis is horizontal, its output will be 0 g, and it will continue to be 0 g if mounted in an automobile traveling at a constant velocity on a level road. When the driver presses on the brake or gas pedal, the accelerometer will register positive or negative acceleration.

If the accelerometer is rotated by 90° so that it is vertical, it will read +1 g upwards even though stationary. In that situation, the accelerometer is subject to two forces: the gravitational force and the ground reaction force of the surface it is resting on. Only the latter force can be measured by the accelerometer, due to mechanical interaction between the accelerometer and the ground. The reading is the acceleration the instrument would have if it were exclusively subject to that force.

A three-axis accelerometer will output zero‑g on all three axes if it is dropped or otherwise put into a ballistic trajectory (also known as an inertial trajectory), so that it experiences "free fall", as do astronauts in orbit (astronauts experience small tidal accelerations called microgravity, which are neglected for the sake of discussion here). Some amusement park rides can provide several seconds at near-zero g. Riding NASA's "Vomit Comet" provides near-zero g-force for about 25 seconds at a time.

See also

- Artificial gravity

- Earth's gravity

- Gravitational acceleration

- Gravitational interaction

- Hypergravity

- Load factor (aeronautics)

- Peak ground acceleration – g-force of earthquakes

- Prone pilot

- Relation between g-force and apparent weight

- Shock and vibration data logger

- Shock detector

- Supine cockpit

Notes and references

- ^ Deziel, Chris. "How to Convert Newtons to G-Force". sciencing.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ G Force Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Newton.dep.anl.gov. Retrieved on 14 October 2011.

- ^ Sircar, Sabyasachi (12 December 2007). Principles of Medical Physiology. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-58890-572-7. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "SI Units – Length". NIST. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ BIPM: Declaration on the unit of mass and on the definition of weight; conventional value of gn Archived 16 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Symbol g: ESA: GOCE, Basic Measurement Units Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, NASA: Multiple G Archived December 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Astronautix: Stapp Archived March 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Honeywell: Accelerometers Archived February 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Sensr LLC: GP1 Programmable Accelerometer Archived February 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Farnell: accelometers[permanent dead link], Delphi: Accident Data Recorder 3 (ADR3) MS0148 Archived December 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, NASA: Constants and Equations for Calculations Archived January 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Jet Propulsion Laboratory: A Discussion of Various Measures of Altitude Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Recording Automotive Crash Event Data Archived April 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

Symbol G: Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center: ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS: BIOMEDICAL RESULTS OF APOLLO, Section II, Chapter 5 Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Honywell: Model JTF, General Purpose Accelerometer - ^ "Pulling G's". Go Flight Medicine. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Robert V. Brulle (2008). Engineering the Space Age: A Rocket Scientist Remembers (PDF). Air University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-58566-184-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Balldin, Ulf I. (2002). "Chapter 33: Acceleration effects on fighter pilots.". In Lounsbury, Dave E. (ed.). Medical conditions of Harsh Environments. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: Office of The Surgeon General, Department of the Army, United States of America. ISBN 9780160510717. OCLC 49322507. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ a b George Bibel. Beyond the Black Box: the Forensics of Airplane Crashes. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8018-8631-7.

- ^ Burton RR (1988). "G-induced loss of consciousness: definition, history, current status". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 59 (1): 2–5. PMID 3281645.

- ^ Brown, Robert G (1999). On the edge: Personal flying experiences during the Second World War. GeneralStore PublishingHouse. ISBN 978-1-896182-87-2.

- ^ DeHart, Roy L. (2002). Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine: 3rd Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ "NASA Physiological Acceleration Systems". 20 May 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ NASA Technical note D-337, Centrifuge Study of Pilot Tolerance to Acceleration and the Effects of Acceleration on Pilot Performance Archived 17 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, by Brent Y. Creer, Captain Harald A. Smedal, USN (MC), and Rodney C. Wingrove, figure 10

- ^ NASA Technical note D-337, Centrifuge Study of Pilot Tolerance to Acceleration and the Effects of Acceleration on Pilot Performance Archived 17 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, by Brent Y. Creer, Captain Harald A. Smedal, USN (MC), and Rodney C. Vtlfngrove

- ^ Fastest Man on Earth – John Paul Stapp Archived 15 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Ejection Site. Retrieved on 14 October 2011.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (16 November 1999). "John Paul Stapp, 89, Is Dead; 'The Fastest Man on Earth'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "New details from horror crash". News.com.au. 16 October 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Q&A: Kenny Brack". Crash.net. 13 October 2004. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ de Souza, T.A.J.; et al. (2017). "Survival potential of the anhydrobiotic nematode Panagrolaimus superbus submitted to extreme abiotic stresses. ISJ-Invertebrate Survival Journal". Invertebrate Survival Journal. 14 (1): 85–93. doi:10.25431/1824-307X/isj.v14i1.85-93.

- ^ de Souza, T.A.J.; et al. (2018). "Caenorhabditis elegans Tolerates Hyperaccelerations up to 400,000 x g. Astrobiology". Astrobiology. 18 (7): 825–833. doi:10.1089/ast.2017.1802. PMID 29746159. S2CID 13679378.

- ^ Than, Ker (25 April 2011). "Bacteria Grow Under 400,000 Times Earth's Gravity". National Geographic- Daily News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Deguchi, Shigeru; Hirokazu Shimoshige; Mikiko Tsudome; Sada-atsu Mukai; Robert W. Corkery; Susumu Ito; Koki Horikoshi (2011). "Microbial growth at hyperaccelerations up to 403,627 × g". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (19): 7997–8002. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.7997D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018027108. PMC 3093466. PMID 21518884.

- ^ Stanford University: Gravity Probe B, Payload & Spacecraft Archived October 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, and NASA: Investigation of Drag-Free Control Technology for Earth Science Constellation Missions. The TRIAD 1 satellite was a later, more advanced navigation satellite that was part of the U.S. Navy's Transit, or NAVSAT system.

- ^ "Toyota Sienna 0–60 Times and Quarter Mile". autofiles.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ a b Allen M.E.; Weir-Jones I; et al. (1994). "Acceleration perturbations of daily living. A comparison to 'whiplash'". Spine. 19 (11): 1285–1290. doi:10.1097/00007632-199405310-00017. PMID 8073323. S2CID 41569450.

- ^ FORMULA 1 (31 March 2017). "F1 2017 v 2016: G-Force Comparison". YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ 6 g has been recorded in the 130R turn at Suzuka circuit, Japan. "Formula 1™ – the Official F1™ Website". Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012. Many turns have 5 g peak values, like turn 8 at Istanbul or Eau Rouge at Spa

- ^ NASA: Table 2: Apollo Manned Space Flight Reentry G Levels Lsda.jsc.nasa.gov

- ^ "Russia trains Greek Tor-M1 crews". RIA Novosti. 27 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ "FIA CONCLUDES INVESTIGATION INTO ROMAIN GROSJEAN'S ACCIDENT AT 2020 BAHRAIN FORMULA 1 GRAND PRIX AND RELEASES 2021 CIRCUIT RACING SAFETY INITIATIVES". www.fia.com. 5 March 2021. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Several Indy car drivers have withstood impacts in excess of 100 G without serious injuries." Dennis F. Shanahan, M.D., M.P.H.: Human Tolerance and Crash Survivability Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, citing Society of Automotive Engineers. Indy racecar crash analysis. Automotive Engineering International, June 1999, 87–90. And National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Recording Automotive Crash Event Data Archived 5 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellor, Andrew. "Formula One Accident Investigations." SAE Technical Paper 2000-01-3552 (2000). https://doi.org/10.4271/2000-01-3552.

- ^ Fang Shen, S. T. Wu, Xueshang Feng, Chin-Chun Wu (2012). "Acceleration and deceleration of coronal mass ejections during propagation and interaction". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 117 (A11). Bibcode:2012JGRA..11711101S. doi:10.1029/2012JA017776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "OMEGA Watches: FAQ". 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "F1: Stunning data about the Cosworth V-8 Formula 1 engine – Auto123.com". Auto123.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ S. N. Patek, W. L. Korff & R. L. Caldwell (2004). "Deadly strike mechanism of a mantis shrimp" (PDF). Nature. 428 (6985): 819–820. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..819P. doi:10.1038/428819a. PMID 15103366. S2CID 4324997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "L3 IEC". Iechome.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ (rpm·π/30)2·0.072/g

- ^ Bittel, Jason. "Dracula ant's killer bite makes it the fastest animal on Earth". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Nüchter Timm; Benoit Martin; Engel Ulrike; Özbek Suat; Holstein Thomas W (2006). "Nanosecond-scale kinetics of nematocyst discharge". Current Biology. 16 (9): R316 – R318. Bibcode:2006CBio...16.R316N. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.089. PMID 16682335.

- ^ (7 TeV/(20 minutes·c))/proton mass

- ^ Green, Simon F.; Jones, Mark H.; Burnell, S. Jocelyn (2004). An Introduction to the Sun and Stars (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-521-54622-5. Extract of page 322 note: 2.00×1012 ms−2 = 2.04×1011 g

- ^ (42 geV/85 cm)/electron mass

Further reading

- Faller, James E. (November–December 2005). "The Measurement of Little g: A Fertile Ground for Precision Measurement Science". Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 110 (6): 559–581. doi:10.6028/jres.110.082. PMC 4846227. PMID 27308179.

External links

- "How Many Gs Can a Flyer Take?", October 1944, Popular Science—one of the first detailed public articles explaining this subject

- Enduring a human centrifuge at the NASA Ames Research Center at Wired

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]

- [4]

- HUMAN CAPABILITIES IN THE PRONE AND SUPINE POSITIONS. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY