18th-century French literature

|

French |

| Authors • Lit categories |

|

French literary history Medieval |

|

Literature by country |

|

Portals |

18th-century French literature is French literature written between 1715, the year of the death of King Louis XIV of France, and 1798, the year of the coup d'État of Bonaparte which brought the Consulate to power, concluded the French Revolution, and began the modern era of French history. This century of enormous economic, social, intellectual and political transformation produced two important literary and philosophical movements: during what became known as the Age of Enlightenment, the Philosophes questioned all existing institutions, including the church and state, and applied rationalism and scientific analysis to society; and a very different movement, which emerged in reaction to the first movement; the beginnings of Romanticism, which exalted the role of emotion in art and life.

In common with a similar movement in England at the same time, the writers of 18th century France were critical, skeptical and innovative. Their lasting contributions were the ideas of liberty, toleration, humanitarianism, equality, and progress, which became the ideals of modern western democracy.

Context

The 18th century saw the gradual weakening of the absolute monarchy constructed by Louis XIV. Its power slipped away during the Regency of Philippe d'Orléans, (1715–1723) and the long regime of King Louis XV, when France lost the Seven Years' War with England, and lost much of its empire in Canada and India. France was forced to recognize the growing power of England and Prussia. The Monarchy finally ended with King Louis XVI, who was unable to understand or control the forces of the French Revolution. The end of the century saw the birth of the United States, with the help of French ideas and military forces; the declaration of the French Republic in 1792, and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, setting the stage for the history of modern France

The 18th century also brought enormous social changes to France; an enormous growth in population; and, even more important, the growth of the wealthy class, thanks to new technologies (the steam engine, metallurgy), and trade with France's colonies in the New World and India. French society was hierarchal with the Clergy (First Estate) and Nobility (Second Estate) at the top and The Third Estate who included everyone else. Members of the Third Estate, especially the more wealthy and influential, began to challenge the cultural and social monopoly of the aristocracy; French cities began to have their own theaters, coffee houses and salons, independent of the aristocracy. The Rise of the Third Estate was influential in the overthrow of the monarchy in the French Revolution in 1789.

French thinking also evolved greatly, thanks to major discoveries in science by Newton, Watt, Volta, Leibniz, Buffon, Lavoisier, and Monge, among others, and their rapid diffusion throughout Europe through newspapers, journals, scientific societies, and theaters.

Faith in science and progress was the driving force behind the first French Encyclopedia of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. The authority of the Catholic Church was weakened, partly by the conflicts between high and low clergy, partly by the conflict between the State and Jesuits, who were finally expelled from the Kingdom in 1764. The Protestants achieved legal status in France in 1787. The church hierarchy was in continual battle with the Lumieres, having many of their works banned, and causing French courts to sentence a Protestant, Jean Calas, to death in 1762 for blasphemy, an act which was strongly condemned by Voltaire.

The explorations of the New World and the first encounters with American Indians also brought a new theme into French and European Literature; exoticism, and the idea of the Noble Savage, which inspired such works as Paul et Virginie by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre. The exchange of ideas with other countries also increased. British ideas were particularly important, particularly such ideas as constitutional monarchy and romanticism, which greatly influenced French writers, particularly in the following century.

The visual arts of the 18th century were highly decorative and oriented toward giving pleasure, as exemplified by the Regency style and Louis XV style, and the paintings of François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Watteau and Chardin, and portrait painters Quentin de La Tour, Nattier and Van Loo. Toward the end of the century, a more sober style appeared, aimed at illustrating scenery, work, and moral values exemplified by Greuze, Hubert Robert and Claude Joseph Vernet. The leading figures in French music were François Couperin and Jean-Philippe Rameau, but they were overshadowed by other European composers of the century, notably Vivaldi, Mozart Haendel, Bach, and Haydn.

For art and architecture in the 18th century, see French Rococo and Neoclassicism

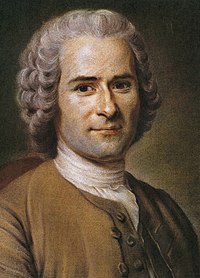

The Philosophes and the literature of ideas

Continuing the work of the so-called "Libertines" of the 17th century, and the critical spirit of such writers as Bayle and Fontenelle, (1657–1757), the writers who were called the lumières denounced, in the name of reason and moral values, the social and political oppressions of their time. They challenged the idea of absolute monarchy and demanded a social contract as the new basis of political authority, and demanded a more democratic organization of central power in a constitutional monarchy, with a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government (Montesquieu, Diderot, and Rousseau.)[1] Voltaire fought against the abuses of power by the government, such as censorship and letters of cachet, which allowed imprisonment without trial, against the collusion of the church and monarchy, and for an "enlightened despotism" where kings would be advised by philosophers.[2]

These writers, and others such as the Abbé Sieyès, one of the main authors of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, became known as the philosophes. They came from the wealthy upper class or Third Estate, sought a society founded upon talent and merit, rather than a society based on heredity or caste. Their ideas were strongly influenced by those of John Locke in England. They introduced the values of liberty and equality which became the ideals of the French Republic founded at the end of the century.[3] They defended the freedom of conscience and challenged the role of religious institutions in society. For them, tolerance was a fundamental value of society. When the Convention placed the ashes of Voltaire in the Pantheon in Paris, they honored him as the man who "taught us to live as free men."

While the philosophes had widely different approaches, they all had as a common objective, both for humanity and for individuals, the ideal of happiness (bonheur). Some, like Rousseau, dreamed of the happiness of the noble savage, rapidly disappearing; others, like Voltaire, sought happiness in a life of the worldly pursuit of refinement. The philosophes were optimists, and they saw their mission clearly; they did not simply observe, but agitated ceaselessly for the achievement of their goals.

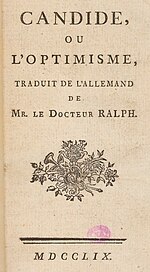

The important works of the philosophes belonged to a variety of different genres, such as the tale illustrating a particular philosophical point;(Zadig (1747) or Candide (1759), both by Voltaire in 1759); or satire on French life disguised as letters from an exotic country (Lettres persanes by Montesquieu in 1721); or essays (The Spirit of the Laws by Montesquieu in 1748, An Essay on Tolerance by Voltaire in 1763; The Social Contract by Rousseau in 1762; The Supplement to a voyage of Bougainville by Diderot, or The History of the Two Indias by the Abbé Guillaume-Thomas Raynal).

The comedies of Marivaux and of Beaumarchais also played a part in this debate about and diffusion of great ideas. The monumental work of the philosophes was the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, the famous encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert, published in thirty-five volumes, with texts and illustration, from 1750 until 1772, accompanied by a large variety of essays, speeches, dialogues and interviews on all aspects of knowledge.[4]

French theater in the 18th century

The great French playwrights of the 17th century, Molière, Racine and Corneille, continued to exert a great influence on the Comédie-Française, but new life was brought into French theater by the tragedies of Voltaire, which introduced modern themes while keeping the classical forms of the alexandrine, as in the play Zaïre in 1732, and The Fanaticism of Mohamet in 1741, both of which enjoyed great success. Nonetheless, royal censorship was still active in the theater under King Louis XV and Louis XVI, and, despite his popularity, Beaumarchais had great difficulty getting his play The Marriage of Figaro staged in Paris, because of its political message.[5]

The relaxing of morals under the French Regency brought the return in 1716 of the Comédie-Italienne, which had been driven out of Paris under Louis XIV. It also saw a period of great theatrical spectacles; crowds went to the theater to see famous actors and to laugh at the characters introduced by the Italian commedia dell'arte, such as Harlequin, Columbine and Pantalone. This was the genre used by Marivaux (1688–1763), with comedies which combined a perceptive analysis of the sentiments of love, subtle verbal play, and an analysis of the problems of society, all done through a clever use of the relationship between the master and his valet. His major works include Les Fausses Confidences (1737), le Jeu de l'amour et du hasard (1730), and l'Île des esclaves (1725).[6]

Jean-François Regnard and Alain-René Lesage (1668–1747) also had great success with comedies of manners, such as Regnard's Le Légataire universel, and Lesage's Turcaret in 1709. But the greatest author of French comedies in the 18th century was Beaumarchais (1732–1799), who displayed a mastery of dialogue and intrigue combined with social and political satire through the character of Figaro, a valet who challenges the power of his master, who is featured in two major works; le Barbier de Séville (1775) and le Mariage de Figaro (1784).

The theater of the 18th century also introduced two new genres, now considered minor, which both strongly influenced the French theater in the following century; the "Comedy of Tears" (comédie larmoyante) and the bourgeois drama (drame bourgeois) which told stories full of pathos in a realistic setting, and which concerned the lives of bourgeois families, rather than aristocrats. Some popular examples of these genres were the Le Fils naturel (The Natural Son) by Diderot in 1757; Le Père de famille (The Father of the Family) by Diderot in 1758; Le Philosophe sans le savoir (The Philosopher who did not know he was a Philosopher) by Michel-Jean Sedaine, (1765); La Brouette du vinaigrier (The Vinegar Cart) by Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1775); and La Mère Coupable (The Guilty Mother) by Beaumarchais, (1792).

The 18th century also saw the development of new forms of musical theater, such as the vaudeville theater, and the opéra comique, as well as a new genre of literary writing about theater, such as Diderot's Paradoxe sur le comédien; the writings of Voltaire defending theater actors against the condemnation of the church; and Rousseau's condemnation of immorality in the theater.

The French novel in the 18th century

The novel in the 18th century saw innovations in form and content which opened the way for the modern novel, a work of fiction in prose recounting the adventures or the evolution of one or several characters. In the 18th century the genre of the novel enjoyed a great increase in readership, and was marked by the effort to convey feelings realistically, through such literary devices as first-person narration, exchanges of letters, and dialogues, all trying to show, in the spirit of the lumieres, a society which was evolving. The French novel was strongly influenced by the English novel, through the translation of the works of Samuel Richardson, Jonathan Swift, and Daniel Defoe.[7]

The novel of the 18th century explored all the potential devices of a novel - different points of view, surprise twists of the plot, engaging the reader, careful psychological analysis, realistic descriptions of the setting, imagination, and attention to form. The texts of the period are difficult to neatly divide into categories, but they can loosely be divided into several subgenres.

The philosophical tale

This category includes the contes philosophiques of Voltaire, Zadig (1747) and Candide (1759), and also the later novella, l'Ingénu, (1768) in which Voltaire moved away from fantasy and introduced a large part of social and psychological realism.

The realistic novel

This subgenre combined social realism with stories about men and women looking for love. Examples include la Vie de Marianne (1741), and Le Paysan parvenu (1735) by Marivaux; Manon Lescaut (1731) by the abbé Antoine François Prévost (1731) and Le Paysan perverti (The Perverse Peasant) (1775), a novel in the form of letters by Nicolas-Edme Rétif (1734–1806). Within this subgenre is a sub-subgenre of realistic novels about love influenced by Spanish literature; novels full of satire, a variety of different social milieux, and young men learning their way in the new world. The classic example is Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane by Alain-René Lesage (1715).

The novel of the imagination

The novel of the imagination pictured life centuries in the future; L'An 2440, rêve s'il en fut jamais (The year 2440 - dream of all dreams) by Mercier (1771); or stories of fantasy le Diable amoureux (The Devil in Love) of Jacques Cazotte (1772).

The libertine, or erotic novel

The libertine, or erotic novel, featured eroticism, seduction, manipulation, and social intrigue. Classic examples are Les Liaisons dangereuses (Dangerous Liaisons) by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos (1782); Justine ou les Malheurs de la vertu (Justine or the misfortunes of virtue) by Donatien Alphonse François de Sade (the Marquis de Sade) (1797); Le Sopha- conte moral (The Sopha - a moral tale) by Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon (1745), and les Bijoux indiscrets (The indiscreet jewels) (1748) and La Religieuse (The Nun) by Diderot (1760).

The novel of feelings

The novel of feelings appeared in the second half of the 18th century, with the publication of Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (Julie, or the New Heloise), in a novel in the form of letters, written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1761). It was modelled after the English novel Pamela by Samuel Richardson, which was the best-selling novel of the century, drawing readers by its pre-romantic depiction of nature and romantic love. Another popular example was Paul et Virginie by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1787).

The novel broken apart

The romans éclatés, roughly translated "Novels broken apart", such as Jacques le fataliste et son maître (Eng: Jacques the Fatalist and His Master) (1773) and le Neveu de Rameau (Eng: The Nephew of Rameau) (1762) by Diderot are almost impossible to classify, but resemble the modernist novels that would come a century or more later.

The birth of the autobiography in the 18th century

Literary stories of people's lives were popular throughout the 18th century, with such popular books as la Vie de mon père (Eng: The Life of My Father) (1779) and Monsieur Nicolas (1794) by Nicolas-Edme Rétif, but the success of the century was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who founded the genre of the modern autobiography with les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire (The dreams of a solitary walker) in 1776, and Les Confessions in 1782, which became the models for all novels of self-discovery.

French poetry of the 18th century

Voltaire used verse with great skill in his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (Poem on the Lisbon Disaster) and in le Mondain (The Man About Town), but his poetry was in the classical school of the 17th century. Only a few French poets of the 18th century have an enduring reputation; they include Jacques Delille (1738–1813), for les Jardins (The Gardens), in 1782; and Évariste de Parny (1753–1814) for Élégies in 1784, who both contributed to the birth of romanticism and to the poetry of nature and nostalgia.

The poet of the 18th century best-known today is André Chénier (1762–1794), who created an expressive style in his famous la Jeune Tarentine (The Young Tarentine) and la Jeune Captive (The Young Captive), both published only in 1819, long after his death during the Terror of the French Revolution.

Fabre d'Églantine was known both for his songs, such as Il pleut, il pleut, bergère) (It's raining, shepherdess) and for his participation in the writing of the new French Republican Calendar created during the French Revolution.

Other genres of 18th century French literature

- The genre of modern art criticism was launched by Diderot in Salons, in which he analyzed the way emotions could be created by works of art, using the example of the feelings inspired by the poetic ruins painted by Hubert Robert.

- Georges-Louis Leclerc, Count of Buffon, popularized the scientific discoveries of his century with the massive Histoire naturelle (Natural History), published with great success between 1749 and 1789.

- During the French Revolution, political speeches became a popular genre of literature with the publication of the speeches of such talented orators as Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, Georges Danton and Maximilien Robespierre.

Conclusions

French literature in the 18th century offered a rich collection of works in all genres, and brought together, rather than opposed, the philosophical and analytical views of the Philosophes and Lumieres with the more subjective and personal views of the emerging romantic movement. Many of the works of the 18th century are forgotten, but the century also produced a number of writers who were great both for the originality and importance of their ideas and for their literary talent; writers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Diderot and Beaumarchais, whose ideas are still quoted today. They used their novels and plays as weapons which profoundly changed their society, while expressing their own personalities and feelings. Thanks largely to these writers, in the 18th century French became the language of culture, political and social reform all across Europe, and as far away as America and Russia.[8]

References

- ^ Rousseau wrote "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains", in the Social Contract (1762). The idea was adapted by Thomas Jefferson 14 years later in the American Declaration of Independence.

- ^ Voltaire wrote, "It is better to risk saving a guilty person than to condemn an innocent one." (Zadig, 1747, ch.6.)

- ^ It was Montesquieu who composed the classical definition of liberty: "Liberty consists of being able to do what you want to do, and not being forced to do what you do not want to do." (Of the Spirit of the Laws) In the same work he added, "Liberty is the right to do all that the laws allow."

- ^ "Nothing is more indisputable than the existence of our senses", Jean Le Rond d'Alembert wrote in the preliminary discourse of Volume One of the Encyclopedia, setting the tone for the systematic examination of all knowledge that followed.

- ^ In 1784, a performance of The Marriage of Figaro was forbidden at Versailles, so it was performed instead at a private theater. One reason for the ban was a monologue by Figaro to his master, saying, "Because you are a great lord, you believe that you are a great genius! Nobility, fortune, rank, places, all that makes you so proud! But what have you done for so many advantages? You took the pain of being born, that's all - as for the rest, you are a rather ordinary man." Quoted in Marco Ferro, Histoire de France pg. 201.

- ^ "In this world", Merivaux wrote, "you must be a bit too kind in order to be kind enough." (Le Jeu de l'Amour et du Hasard, 1730. act 1, scene 2.)

- ^ "There exists one book", Rousseau wrote, "which, to my taste, furnishes the happiest treatise of natural education. What then is this marvelous book? Is it Aristotle? Pliny? Is it Buffon? No - it is Robinson Crusoe.' (Emile, ou De l'education (1762).

- ^ The works of Montesquieu and Rousseau were sources for Thomas Jefferson and the other founders of the United States, while Voltaire's ideas were first welcomed and then violently rejected by Russian Empress Catherine the Great. See Orlando Figes, Natasha's Dance - A Cultural History of Russia, Metropolitan Books, 2002.

Bibliography

- Robert Mauzi, Sylvaine Menant, Michel Delon, Précis de Littérature Française du XVIIIe Siècle, Presses Universaires de France, 1990

- Marc Ferro, Histoire de France, Éditions Odile Jacob, Paris, 2001

- Michel Delon, Pierre Malandain, Littérature française du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1996.

- Béatrice Didier, Histoire de la littérature française du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Nathan, 1992.

- Jean-Marie Goulemot, Didier Masseau, Jean-Jacques Tatin-Gourier, Vocabulaire de la littérature du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Minerve, 1996.

- Michel Kerautret, La Littérature française du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1983.

- Michel Launay, Georges Mailhos, Introduction à la vie littéraire du XVIIIe siècle, avec la collaboration de Claude Cristin et Jean Sgard, Paris, Bordas, 1984.

- Nicole Masson, Histoire de la littérature française du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, H. Champion, 2003.

- François Moureau, Georges Grente, Dictionnaire des lettres françaises. Le XVIIIe siècle, Paris, Fayard, 1995.

- Complete Works of Voltaire Archived 2010-10-13 at the Wayback Machine (Œuvres complètes de Voltaire), Oxford, Voltaire Foundation, 1968- .