Frank O'Connor (actor, born 1897)

Frank O'Connor | |

|---|---|

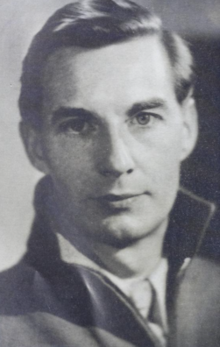

O'Connor in the late 1920s, photographed by Melbourne Spurr[1] | |

| Born | Charles Francis O'Connor September 22, 1897 Lorain, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 9, 1979 (aged 82) New York City, U.S. |

| Burial place | Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | |

Charles Francis "Frank" O'Connor (September 22, 1897 – November 7, 1979) was an American actor, painter, and rancher and the husband of novelist Ayn Rand. Frank O'Connor performed in several films, typically as an extra, during the silent and early sound eras. While working on the set of the 1927 film The King of Kings, O'Connor met Rand, and they eventually dated each other steadily. They married in 1929. When O'Connor and Rand moved to California so Rand could work on the movie adaptation of her novel The Fountainhead, O'Connor purchased and managed a ranch in the San Fernando Valley for several years. In addition to raising numerous flora and fauna on the ranch, he there developed the Lipstick and Halloween hybrids of Delphinium and Gladiolus.

After the couple moved to New York City in 1951, he took up painting and became a member of the Art Students League of New York. He provided the cover art for some of Rand's published work after this time. Rand attributed to O'Connor inspiration for some of the themes and characters in her writing, and he provided the title for her novel Atlas Shrugged.

In 1954, Rand pressured O'Connor into assenting to her having a sexual affair with Nathaniel Branden. The affair deeply troubled O'Connor and lasted until 1968. Late in his life, O'Connor struggled with excessive alcohol consumption. He died in 1979 and was buried in Kensico Cemetery. After Rand died in 1982, she was buried alongside him.

According to cognitive psychologist Robert L. Campbell, O'Connor "eludes" Rand's biographers.[2] Rand said that O'Connor was an inspiration for her writing and the model for her idealized male protagonists, like Howard Roark and John Galt. Other associates of Rand and O'Connor have objected and said that Rand's claims about O'Connor's personality were inaccurate and that their marriage struggled because he was more soft-spoken and gentle than she preferred.

Biography

Early life

Charles Francis "Frank" O'Connor was born September 22, 1897, in Lorain, Ohio to steelworker Dennis O'Connor and homemaker Mary Agnes O'Connor, the third of their seven children.[3][4] Although raised Catholic, Frank O'Connor dropped out of his Catholic school when he was fourteen years old, and he was atheist thereafter.[5] When he was fifteen, his mother died, and O'Connor and three brothers left Ohio to live on their own; the four of them moved to New York, where O'Connor began an acting career. O'Connor moved to Hollywood, where most American film studios were by then, sometime around 1926.[6]

Acting

In Hollywood, O'Connor worked part-time in acting, primarily as a film extra.[7] His first Hollywood role was as a Roman legionnaire in Cecil B. DeMille's The King of Kings, and he first met Rand on the film's set.[8] As an adult, O'Connor was "mesmerizingly handsome", according to cultural analyst Lisa Duggan,[9] and Rand was smitten with O'Connor virtually at first sight. To get his attention, Rand intentionally tripped O'Connor, whereupon he apologized for stepping on her, and they shared their names with each other.[10]

O'Connor ran into Rand again at a public library in Hollywood, and this time they kept in touch and began courting, going to movies and having dinner with each other and with O'Connor's brothers Joe and Harry. O'Connor was most likely Rand's first kiss.[11]

Perhaps partly in order to help her obtain legal residence before her temporary visa expired, O'Connor married Rand on April 15, 1929, in the Los Angeles City Hall of Justice.[12] After marrying, O'Connor eked out a modest life with Rand, and they both worked odd jobs.[13] Rand was, in the words of historian Jennifer Burns, "the breadwinner from the start".[14] Soon, however, O'Connor's acting career improved, and for a few years he had regular employment in small roles for early talkies.[15] With his income, O'Connor also provided for Rand, including by buying her a writing desk and a typewriter. O'Connor also took the lead in decorating their apartment.[15]

O'Connor performed in several films released in 1933 and 1934, though he continued landing relatively small roles, sometimes as humorous characters; this dismayed Rand, who believed he deserved to play a romantic lead.[16] O'Connor featured in a speaking role as Jake Canon for both the film and stage versions of As Husbands Go.[17][a] The Austin Daily Texan complimented the film's entire cast in its review, stating that "the stars and the supporting cast are discerningly chosen, fit their roles exactly, and enact them to the uttermost nuance of perfection."[18]

When Rand received a producer's offer to take her play Night of January 16th to Broadway, she convinced O'Connor to move with her to New York City; they departed in November and arrived in December.[19] In New York, O'Connor's career idled, and he joked that he was "Mr. Ayn Rand" as she was the breadwinner while he took care of paying bills, doing household chores, and decorating their apartments.[20]

O'Connor landed roles for summer stock theater in Connecticut in 1936 and 1937. In August 1936, he temporarily moved to Connecticut to perform in Night of January 16th as Guts Regan.[21] O'Connor returned to Connecticut in July 1937, this time accompanied by Rand, and they stayed in Stony Creek where he performed for several plays, including reprising his role as Guts Regan for Night of January 16th.[22]

Although O'Connor was not particularly intellectual the way Rand was, he was socially adept. At social gatherings, he secretly passed Rand notes with suggestions about what to talk about, and she found his sense of humor hilarious.[23] With each other, they could be silly; O'Connor nicknamed Rand "Fluffy", and she called him "Cubbyhole".[24]

After overhearing a phone conversation between Rand and Isabel Paterson during the summer of 1943 in which Rand mentioned that "all the creative minds in the world [going] on strike… would make a good novel", O'Connor affirmed to her "That would make a good novel." This idea eventually became Atlas Shrugged.[25]

Ranching

When Rand sold the film rights to her novel The Fountainhead and was called on to write the script for a movie adaptation, O'Connor moved with Rand back to California in December 1943.[26] While they started out in a small apartment in Hollywood, O'Connor researched purchasing land in the San Fernando Valley. O'Connor picked out a Richard Neutra house with thirteen acres of land in an area that later became Chatsworth, and O'Connor and Rand bought it and moved into it in 1943.[27] "Reinventing himself as a gentleman farmer," in historian Jennifer Burns's words, O'Connor "thrived in California".[28] He tended the San Fernando property's acres, gardens, and orchards as a working ranch.[29] He raised peacocks, chickens, and rabbits on the property and tended flowers, fruit trees, and gardens.[30] O'Connor developed a skill for horticulture and raised alfalfa, bamboo, blackberries, chestnuts, pomegranate trees, and gladioli; he earned some money selling alfalfa and extra produce, and after learning flower arranging he sold gladiolas to hotels in Los Angeles.[31] By breeding delphiniums and gladiolas in a greenhouse, he created two new hybrids: Lipstick and Halloween.[32] O'Connor once joked to a friend that his activity was "Not the sort of thing Howard Roark would do!"[33] He tended the property with great satisfaction and happiness.[34]

The August 1949 edition of House and Garden featured the San Fernando Valley ranch, along with O'Connor and Rand, calling it "a steel house with a suave finish".[35] House and Garden complimented the property's "[m]assed evergreens" which gave "depth and shade" to the house's porte-cochère, the "arresting pattern" of philodendron above the living room fireplace, and the "enrich[ing]" effect of colorful gladiolus.[36] O'Connor managed the ranch from 1944 to 1951.[37]

In 1950, O'Connor and Rand became acquainted with Nathaniel Blumenthal (later Branden) and Barbara Weidman, whom the O'Connors took to calling "the children".[38] When Branden and Weidman moved to New York City for graduate university studies, Rand, missing Branden who had become an important intellectual disciple and emotional connection, pressed O'Connor to join her in moving back to New York to be near Branden and Weidman, despite how happy the ranching life made him.[39] O'Connor made the cross-country trip with Rand to New York City in 1951.[40] According to friend Ruth Hill, Rand told O'Connor that the New York move would be temporary and they would return to the ranch (O'Connor even asked the Hills to take care of his flowers until he was back[41]) but that Rand never actually planned on doing so. They never returned to California, and eventually sold the Chatsworth property in 1962.[42]

Painting

In New York City, O'Connor obtained part-time work as a florist, making flower arrangements for hotels.[43] He also took up visual art with what archivist Jeff Britting calls "serious interest", drawing sketches and painting people, urban landscapes and floral still lifes. Some observers thought O'Connor was a talented artist, albeit unrefined and untrained.[44] He became a member of the Art Students League of New York, and Ilona Royce Smithkin mentored him.[45] His "most important artwork", according to cognitive psychologist Robert L. Campbell, was a portrait of Ayn Rand he painted in 1961.[46] When O'Connor had his own painting studio in the 1960s, Rand sometimes liked to visit his studio to watch him paint; he generally appreciated her attention, though a guest observed that "the only time I ever saw him [O'Connor] lose his temper" was on an occasion when Rand pressed with a criticism and O'Connor insisted she "leave [him] alone".[47]

Branden and Weidman married in 1953, and O'Connor attended the wedding as Branden's best man.[48] As a wedding gift, O'Connor filled the Brandens' new studio apartment with flowers of his arrangement.[49]

In September 1954,[50] Rand and Nathaniel Branden told O'Connor and Barbara Branden that they had fallen in love with each other.[51] Rand and Branden asked that their respective spouses give the two of them time with each other for a romantic but nonsexual relationship; during the conversation, Barbara Branden and O'Connor briefly objected, both raising their voices and saying, "I won't be part of this", but Rand eventually secured their agreement, Barbara Branden recalling that Rand could "spin out a deductive chain from which you just couldn't escape".[52] In November, Rand and Branden invoked Rand's value theory of sexuality to insist that their spouses also give them permission to escalate the affair to a sexual relationship.[53] O'Connor assented, and he vacated the apartment twice a week for Rand and Branden, often going to a bar.[54] There is no known written record by O'Connor of his thoughts on Rand's relationship with Branden, and he only ever discussed it with Rand and the Brandens.[55] Historian Jennifer Burns concludes that of all those involved in the affair, O'Connor may have been "the hardest hit" emotionally.[56]

In 1956, while Rand was writing a novel she up to that point tentatively titled The Strike, O'Connor suggested that she rename it Atlas Shrugged, a phrase which had up to then only been the title of a chapter in the book. Rand adopted Atlas Shrugged as the novel's title.[57] She later averred, "When I couldn't think of a title for one of my novels, he did. He told the whole story in two words".[58] When a circle of Rand's associates threw a party to celebrate Atlas Shrugged's publication, O'Connor put together flower arrangements for the event.[59]

O'Connor oil painted Man Also Rises, which Rand reported was his depiction of a sunset they saw in San Francisco.[60][61] A reproduction of Man Also Rises was used as the cover art for the 1968 twenty-fifth anniversary edition of The Fountainhead; Rand dubbed it "the proper climax of the book's history".[60][62]

O'Connor increased his time and attention spent on painting in the 1960s.[63] The Art Students League was a rare respite in his life, and he wanted to be known there as himself rather than only as Ayn Rand's husband. He eventually won a seat on the league's Board of Control.[64]

Later life

As O'Connor aged, his health declined. A surgery temporarily staved off painful contractions in his hands' tendons in the late 1960s, but the difficulty recurred in 1968, and he withdrew from the Art Students League and resigned from its Board of Control.[65] The Brandens reported often finding him drinking alcohol as Rand pulled him into her increasingly contentious social world, including by having O'Connor be present for difficult conversations between Rand and Nathaniel Branden during the waning period of their affair,[66] before she broke it off in 1968 after learning that Branden was having another affair with a different, younger woman.[67]

O'Connor continued accompanying Rand. He gave her a ring with forty rubies to celebrate their fortieth wedding anniversary in 1969.[68] In 1974, he was a guest, with Rand, to the swearing in of Alan Greenspan (one of Rand's former acolytes in Objectivism) to the Council of Economic Advisers.[69]

In the late 1970s, O'Connor's health worsened further. He mentally declined, fell victim to alcoholism, and eventually became homebound. Sometimes, he could not recognize people; sometimes he refused to eat and was "terribly frightened" when Rand tried to force him. He still retained his habit of standing when a woman entered the room.[70]

O'Connor died on November 7, 1979, at New York Hospital.[58] He was buried in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.[71] When Rand died a few years later, in 1982,[72] she was buried in Kensico next to O'Connor.[71]

Personality

Campbell observes that "on the personal side, it is Frank O’Connor who still eludes every biographer" of Rand.[2] Rand called O'Connor her "top value", and she said he was the model for her fictional protagonists and "as near to" being Fountainhead protagonist Howard Roark as "anyone I know".[73] Others who knew O'Connor aver that Rand mischaracterized O'Connor and that in reality while he was witty, kind, and chivalrous, he was emotionally restrained and very passive.[74] Literary scholar Mimi Gladstein summarizes, "there is not much public evidence to corroborate Rand's" claims about O'Connor.[75] Robert Sheaffer concludes that O'Connor "was a very generous and decent man" but "was no John Galt".[76] Unlike Rand, O'Connor had little interest in books or the ideas she enjoyed thinking about, and he was kind and insisted on politeness.[77] An acquaintance later reported that during their time in the San Fernando Valley, Rand actually considered divorcing him out of frustration with his lack of intellectuality and sexual drive.[78] Despite this tension between them and despite his melancholy, O'Connor consistently supported Rand and never left her.[79]

Legacy

The Passion of Ayn Rand, a 1999 biopic directed by Christopher Menaul and based on the 1986 biography of the same name by Barbara Branden, depicts O'Connor as an unintellectual, gentle man whom Rand becomes frustrated with for not fulfilling her erotic ideal of an aggressive, dominant partner. Peter Fonda performs in the role of O'Connor.[80] Writing for Variety, reviewer David Kronke observed that Fonda lends "an air of Quaalude dependency" to his depiction of O'Connor through acting with a "droopy and curious turn".[81] New York Times reviewer Ron Wertheimer criticized the film as "pretty muddled" but praised Fonda's performance, writing that "only Peter Fonda, as Rand's pathetic husband, Frank O'Connor, is really worth watching" and that "Fonda can't save" the movie but does "make it more interesting".[82] For his performance as O'Connor, Fonda received the 2000 Golden Globe Award for best supporting actor in a series, miniseries, or film made for television.[83][84]

A 2016 Atlas Society article observed that although there were several people with the name Frank O'Connor who were documented in biographical Wikipedia articles, at the time O'Connor was not among them.[4] According to Campbell in a 2013 review essay, "Ayn Rand too often spoke for" O'Connor when they were alive, and since their deaths, followers of Rand's teachings have been "keen on reducing him to a cipher" for their own purposes; O'Connor is "poorly known" despite "his character" and "the support he provided to Rand".[85]

Filmography

Much of O'Connor's acting work was as a film extra, sometimes with unnamed or uncredited roles. This list may be nonexhaustive because whether or not O'Connor appeared in later films is unclear due to the emergence of another actor named Frank O'Connor.[86]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | Orphans of the Storm | [86][b] | ||

| 1927 | The King of Kings | [88] | ||

| 1930 | Shadow of the Law | [15] | ||

| 1931 | Cimarron | [37][58] | ||

| Ladies' Man | News clerk | [89] | ||

| Arrowsmith | [15] | |||

| 1932 | Three on a Match | [37] | ||

| Handle with Care | Police lieutenant | [15] | ||

| 1933 | Goodbye Love | False Department of Justice agent | [86] | |

| Son of Kong | First process server | [86] | ||

| After Tonight | Officer on train | [86] | ||

| Tillie and Gus | [86] | |||

| As Husbands Go | Jake Canon | [37][a] | ||

| 1941 | Caught in the Act | Policeman | [91] |

See also

Notes

Citations

- ^ Britting (2004, pp. 38–39, 132)

- ^ a b Campbell (2013, p. 60).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 65, 93); Burns (2009, p. 23).

- ^ a b Grossman, Jennifer A. (November 9, 2016). "5 Things To Know About Frank O'Connor, Ayn Rand's Husband". The Atlas Society. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022.

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 65–66).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 20, 23) writes that "Frank followed the studios west, arriving in Hollywood around the same time as Rand" and that "Rand arrived in 1926".

- ^ Duggan (2019, pp. 6, 38).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 65–66).

- ^ Duggan (2019, p. 34).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 66).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 67).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 26); Heller (2009, p. 71).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 72).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 26).

- ^ a b c d e Heller (2009, p. 75).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 78). For another view, see Burns (2009, p. 30), who concludes that O'Connor's "acting career had sputtered to an effective end".

- ^ Britting (2004, p. 39); Milgram (2016, p. 25).

- ^ "Reviewed Today". Austin Daily Texan. May 8, 1934. p. 3.

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 30); Heller (2009, pp. 78–82).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 99); Burns (2009, p. 46).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 101).

- ^ Britting (2004, pp. 53–54); Heller (2009, p. 102).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 30–31).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 101); Burns (2009, p. 31). O'Connor and Rand continued using these nicknames with each other for decades; see Britting (2004, p. 96).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 165), italicization in original.

- ^ Britting (2004, p. 68); Heller (2009, p. 161); Duggan (2019, p. 39).

- ^ Britting (2004, pp. 69–70); Heller (2009, pp. 165–166).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 107–108).

- ^ House & Garden (1949, p. 57).

- ^ Gladstein (2010, p. 16); Heller (2009, p. 165).

- ^ Britting (2004, p. 70); Burns (2009, p. 108); Heller (2009, p. 166).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 108).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 224).

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 14).

- ^ House & Garden (1949, p. 54); Burns (2009, pp. 108, 314n20).

- ^ House & Garden (1949, pp. 55–57).

- ^ a b c d Milgram (2016, p. 25).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 225); Burns (2009, p. 136).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 138); Heller (2009, pp. 234–237).

- ^ Britting (2004, p. 79); Burns (2009, p. 138).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 138).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 237).

- ^ Brown (2016, p. 34).

- ^ Britting (2004, p. 109); Heller (2009, p. 238).

- ^ Gladstein (1999, pp. 9–10); Heller (2009, p. 338).

- ^ Campbell (2013, p. 61).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 339).

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 15).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 243).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 254–256).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 155–156).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 256–257).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 257).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 156–157).

- ^ Campbell (2008, p. 151).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 157).

- ^ Gladstein (2000, p. 85).

- ^ a b c "Charles Francis O'Connor, Artist, Husband of the Writer Ayn Rand". The New York Times (obituary). November 12, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Brooks (2003, p. 101).

- ^ a b Long, Roderick T. "Audiovisual Companion to My Spring 2021 Seminar on Nietzsche and Modern Literature". praxeology.net. Archived from the original on January 1, 2023.

- ^ Britting, Jeff (February 14, 2018). "Romantic Love". Impact Today. The Ayn Rand Institute. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023.

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 12); Heller (2009, p. 364).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 339).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 357).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 357, 360).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 360–361).

- ^ Burns (2009, pp. 241–244).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 389).

- ^ Duggan (2019, p. 87).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 402–405); Duggan (2019, p. 110).

- ^ a b Gorry, Mary (April 10, 2012). "Tombstone Tuesday: Ayn Rand, Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, NY". Heritage & Vino. Archived from the original on January 1, 2023.

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 19); Burns (2009, p. 278).

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 9); Heller (2009, p. 184).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 99).

- ^ Gladstein (1999, p. 9).

- ^ Sheaffer (1999, p. 302).

- ^ Heller (2009, pp. 66, 184).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 184).

- ^ Burns (2009, p. 276).

- ^ Downing (2020, pp. 110, 123–125).

- ^ Kronke, David (May 25, 1999). "The Passion of Ayn Rand". Variety (review). Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ Wertheimer, Ron (May 28, 1999). "The Ayn Rand Cliffs Notes: Philosophy as Foreplay". TV Weekend. The New York Times (review). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Fonda, Peter 1939(?)–". Contemporary Theatre, Film and Television. Cengage. May 29, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Johnson (2000, p. 62).

- ^ Campbell (2013, p. 61).

- ^ a b c d e f Hayes, David P. (1998). "Film Credits of Frank O'Connor". Movies of Interest to Objectivists. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022. Heller (2009, p. 446) accepts Hayes's list.

- ^ "Orphans of the Storm (1921)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years, 1893–1993. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Milgram (2016, p. 24).

- ^ Heller (2009, p. 75); Kear & Rossman (2016, pp. 53, 254).

- ^ "As Husbands Go (1933)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years, 1893–1993. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2023. To see the credits, click either the "Full page view" toggle or the "Credits" tab.

- ^ Kear & Rossman (2016, pp. 176, 254).

References

- "A Steel House with a Suave Finish". House and Garden. August 1949. pp. 54–57.

- Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195324877.

- Britting, Jeff (2004). Ayn Rand. Overlook Illustrated Lives. Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 1-58567-406-0.

- Brooks, Dean (Fall 2003). "Rebuttal Witnesses". Journal of Ayn Rand Studies (review). 5 (1): 97–103. ISSN 1526-1018. JSTOR 41560238 – via JSTOR.

- Brown, Susan Love (2016). "Nathaniel Branden's Oedipus Complex". Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 16 (1): 25–40. doi:10.5325/jaynrandstud.16.1-2.0025. ISSN 2169-7132. S2CID 171132344.

- Campbell, Robert L. (July 2013). "An End to Over and Against". Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 13 (1): 46–68. doi:10.5325/jaynrandstud.13.1.0046. ISSN 1526-1018. JSTOR 10.5325/jaynrandstud.13.1.0046.

- Campbell, Robert L. (Fall 2008). "The Peikovian Doctrine of the Arbitrary Assertion". Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 10 (1): 85–170. doi:10.2307/41560376. ISSN 1526-1018. JSTOR 41560376.

- Downing, Lisa (2020). "Selfish Cinema: Sex, Heroism, and Control in Adaptations of Ayn Rand for the Screen". In Cocks, Neil (ed.). Questioning Ayn Rand: Subjectivity, Political Economy, and the Arts. Palgrave Studies in Literature, Culture and Economics. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–129. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53073-0_6. ISBN 978-3-030-53072-3. S2CID 235912743.

- Duggan, Lisa (2019). Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed. American Studies Now: Critical Histories of the Present. Vol. 8. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520294776.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (2000). Atlas Shrugged: Manifesto of the Mind. Twayne's Masterwork Studies. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-1638-6. OL 6780673M.

- Gladstein, Mimi R. (2010). Ayn Rand. Major Conservative and Libertarian Thinkers. Vol. 10. Continuum. doi:10.5040/9781501301339. ISBN 978-0-8264-4513-1.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (1999). The New Ayn Rand Companion (Rev. and expanded ed.). Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30321-5.

- Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. Nan A. Talese/Doubleday. ISBN 9780385529464.

- Johnson, D. Barton (Fall 2000). "Strange Bedfellows: Ayn Rand and Vladimir Nabokov". Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 2 (1): 47–67. ISSN 1526-1018. JSTOR 41560131.

- Kear, Lynn; Rossman, John (2016). The Complete Kay Francis Career Record: All Film, Stage, Radio and Television Appearances. McFarland. ISBN 9781476602875.

- Milgram, Shoshana (2016). "The Life of Ayn Rand: Writing, Reading, and Related Life Events". In Gotthelf, Allan; Salmieri, Gregory (eds.). A Companion to Ayn Rand. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 22–45. doi:10.1002/9781118324950.ch2. ISBN 978-1-4051-8684-1.

- Sheaffer, Robert (1999). "Rereading Rand on Gender in the Light of Paglia". In Gladstein, Mimi Reisel; Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (eds.). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Re-reading the Canon. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 299–318. ISBN 0-271-01831-3.