Faridkot State

| Faridkot State | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princely State of British India | |||||||||

| 1763–1948 | |||||||||

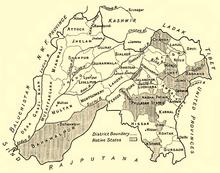

Detail of Faridkot State from a map of British and native states in the Cis-Sutlej Division between 1847–51, by Abdos Sobhan, 1858 | |||||||||

| Capital | Faridkot | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• 1892 | 1,652 km2 (638 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1892 | 97,034 | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||

• Established | 1763 | ||||||||

| 20 August | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Faridkot State was a self-governing princely state of Punjab ruled by Brar Jats[1] outside British India during the British Raj period in the Indian sub-continent until Indian independence. The state was located in the south of the erstwhile Ferozepore district during the British period.[2] The former state had an area of around 1649.82 square kilometres (637 sq mi).[2] It population in 1941 was around 199,000 thousand.[2] The state's rulers had cordial relations with the British.[3]

History

Origin

The formation of a state of Faridkot took many years in the making, with various rulers governing the area with no single authority.[4] It is said that Raja Mokalsi was the founder of the locality of Faridkot and he constructed a fort in Mohalkar in the 12th century.[4] He was succeeded by various rulers of the same dynasty but at some point the dynasty ceased to govern the Faridkot region.[4]

Faridkot State was established in 1763 by Hamir Singh (died 1782[5]), with Faridkot as its capital.[2][5] Faridkot State was founded by Brar Jats.[1] The ruling family of Faridkot State claimed descent from Jaisal.[4] Kotkapura used to be the capital but Hamir Singh shifted the capital to Faridkot.[4] The successive rulers of Faridkot would come from Hamir Singh's lineage.[4]

Colonial period

The Sikh Empire of Ranjit Singh occupied Faridkot State in 1807, whom was eager to conquer the Malwa states.[2][6] The Sikh Empire's annexation over Faridkot State made the other Malwa states anxious as they were threatened by the encroaching Sikh Empire.[6] However, the Malwa states were sandwiched between the Sikh Empire and also the advancing British East India Company, whom had annexed the Marathas and were closing in on the remaining frontier of the last remaining independent states in Punjab and Sindh.[6] The Malwa states decided to side with the British over the Sikh Empire as they believed it would take a long time for the British to overcome them while they were threatened by immediate annexation from the Sikh Empire.[6] Due to the rise of Napoleon back in Europe, the British temporarily ceased their territorial advancements in India.[6] In 1808, the British began to take an interest in Punjab affairs again as their fears of a Franco-Russian attack via the subcontinent went away.[6] The British sided with the Malwa states over the Lahore State.[6]

Control over Faridkot was restored to chief Gulab Singh on 3 April 1809 due to the signing of a treaty between the Lahore Darbar and the British East India Company.[2][6] The Sikh Empire forfeited its claims over the Malwa states south of the Sutlej river, including its claim over Faridkot State.[6] Therefore, the survival of Faridkot State against the advancing Sikh Empire was thanks to intervention by the British.[6] However, the British after this point lost interest in the Faridkot region as it was not a good source of revenue for them.[6]

Faridkot was one of the Cis-Sutlej states, which came under British influence in 1809. It was bounded on the west and northeast by the British district of Ferozepore, and on the south by Nabha State. Gulab Singh died in 1826, being succeeded by his only son Attar Singh.[2][7][4] However, the young Attar Singh would die shortly after in 1827.[2][7][4] The successor to Attar Singh could have been either Attar Singh's uncle, Pahar Singh, or prince Sahib Singh.[4] However, Pahar Singh was the one who succeeded Attar Singh, rather than Sahib Singh.[7][4]

Under Pahar Singh

Pahar Singh is noted for paying particular attention to the common-folk of his dominion, ensuring their welfare.[4] Pahar Singh kept advisors around him to look-after the needs of the civilians in the state and to provide him valuable advice.[4] Some of the useful advisors that Pahar Singh employed were sardars Meenha Singh, Ghamand Singh, and Koma Singh.[4] Furthermore, Pahar Singh awarded his brothers, Sahib Singh and Mehtab Singh, a jagir grant consisting of villages for them to rule-over.[4] Under Pahar Singh, the jungles that surrounded Faridkot were deforested to clear the land for development.[4] A canal branch linking to the Sutlej was constructed, which provided valuable irrigation to the state.[4] However, this initially built canal eventually dried-up and there was an inadequate amount of funds in the state's treasury for the construction of a new one.[4] Therefore, Pahar Singh assisted the local zamindars (landlords) with the construction of a well instead.[4]

The relations between Faridkot State and Lahore State were cold.[4] Diwan Mohkam Chand of the Lahore Darbar and the diwan of Lahore, coveted the state and wished to absorb it.[4] Pahar Singh developed friendly ties with the British in-light of this.[4] During the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1845 the chief, Raja Pahar Singh, was allied with the British, and was rewarded with an increase of territory.[2][6] Pahar Singh had provided the British valuable assistance during the Battle of Mudki.[4] During the Battle of Ferozeshah, the British were accepting their defeat and stepped-back, but the Sikh forces under Lal Singh and Tej Singh had also done the same, leaving valuable weaponry behind such as cannons and other resources at the battleground.[4] After witnessing this, Pahar Singh reported to the British general Bradford about the situation.[4] Due to the request of Pahar Singh, they were able to take possessions of the cannons and other items left behind at the abandoned battlefield.[4] Pahar Singh was bestowed with the raja title by the British in 1846 as a reward for the helped he provided them.[5][6][4]

Pahar Singh married Chand Kaur, who was the daughter of Samand Singh of Deena Wale.[4] Chand Kaur gave birth to a son, Wazir Son.[4] Pahar Singh would marry another woman who was from a Muddki royal lineage.[4] His second-wife would give birth to princes Deep Singh and Anokh Singh.[4] Pahar Singh died at the age of 50.[4] Both Deep Singh and Anokh Singh had died in childhood, leaving Wazir Singh behind as the rightful heir to the Faridkot throne.[4]

Under Wazir Singh

Pahar Singh's successor, Wazir Singh, continued the pro-British policies and relations.[6] Wazir Singh involved himself in statecraft even at a young age, which helped improve his ability to rule later-on.[4] Wazir Singh inherited the throne during a period of peace in the Punjab, allowing him to divert most of his focus on internal politics and projects.[4] Wazir Singh established an administrative division system in the state, where he divided the polity into Faridkot, Deep Singh Wala, Kotakpura, and Bhagta, into separate administrative entities.[4] Faridkot and Kotkapura divisions had tehsils established within them, with a tehsildar being appointed for each tehsil.[4] He also established a policing system, with each division having its own police station with their own inspectors.[4] Wazir Singh also initiated a system of recording land statistics, which had not been done before.[4] This led to the land of the polity being measured, with the Nambardars (village headmen) being consulted for calculating the total hectare amounts.[4] This land surveying project was called Moti Ram Bandobast and documentation related to Sajra, Khushrah, Khatoni, and Khevad were created.[4] He also made reforms to the taxation system, where as before payment was done in food grains, now payments must be done in legal tender (money).[4] The taxation rate was 2 rupees per acre for barren land and 8 rupees per acre for irrigated land.[4] Reforms to the financial system were also conducted by Wazir Singh, whom assumed direct control over it.[4] But Wazir Singh taking control over the finances of the state, it had previously been the responsibility of the dewan, but there was mismanagement going-on under that scheme.[4] Also, Wazir Singh established courts in the state, where the people could have their disputes solved through them.[4] In-regards to business developments, Wazir Singh opened up the first bazaar market in the state in 1861, inviting businessmen from distant places to come there.[4]

In the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Wazir Singh's forces guarded the Sutlej ferries, and destroyed a rebel stronghold.[8][4] He also sent an army of troops to meet the Deputy Commissioner of Ferozepore.[4] Revolutionaries arrested by the Faridkot forces were handed-over to the British.[4] Due to his actions during the war, the British awarded Wazir Singh with the title of Brar Vansh Raja Bahadur.[4] The British also upgraded the amount of honourary cannons for Faridkot from seven to eleven.[4] These rewards were declared by Queen Victoria in a special assembly meeting on 21 April 1863.[4] In the aftermath of the 1857 rebellion, the British stopped their expansionist policies and the surviving princely states were assured of their protection under certain conditions.[6] The British appointed a resident at the court of the larger princely states, enacting indirect control over them.[6] However, Faridkot State was a small state, and thus no British resident was appointed for its court.[6] Rather, Faridkot formed part of the provincial circle under a British representative.[6]

Wazir Singh also paid attention to religious affairs, as he was a believer of the Guru Ghar ("house of the Guru").[4] Wazir Singh gave service to Gurdwara Lohgarh in Dina (present-day Moga district).[4] This location has a special meaning to the Brar community as it is here where Guru Gobind Singh declared the Brar tribe as one of his very own communities as he had wrote and dispatched the Zafarnama epistle from Dina.[4] In his later years, Wazir Singh took his congregation (sangat) along with him to visit religious sites in Haridwar, Calcutta, Allahabad, and Patna.[4] He constructed a Sikh shrine called Gurdwara Sangat Sahib at one of these locations.[4]

Wazir Singh died in 1874, he was succeeded by his son, Bikram Singh (r. 1874–98).[6][4]

Under Bikram Singh

After Bikram Singh rose to the throne in 1874, officials and rulers from other states, such as maharaja Mahendra Singh of Patiala State, came to visit him.[4] Bikram Singh married twice (with the wedding of his second-marriage happening in Patiala), with no children being born from his first-marriage but through his second-marriage, a son named Balbir Singh was born.[4] Some of the projects that were carried-out during the reign of Bikram Singh include the construction of dormitories, gardens (including orchids), bungalows, roads, and market places, and also social welfare efforts.[4] Bikram Singh constructed mandis, which attracted businessmen to the area.[4] He also built fortresses and constructed a palace within the confines of a fort.[4] Before the time of Bikram Singh, the city of Faridkot was confined within the walls of Faridkort Fort, it was through the construction of market-places outside the fort's walls that people began to settle outside of the walls.[4] Bikrom Singh imposed a law called the Aabkar Act, which regulated alcohol in the state.[4] The revenue of the state improved through Bikram Singh's efforts.[4] A quirk about Bikram Singh is he had a habit of collecting money, with him saving up to 1 crore rupees (10,000,000 rupees) in his life.[4] Bikram Singh wished to have all of the polity's land documented, so he hired the British officer Lala Daulat Rai to carry-out the work in 1886.[4] However, in 1891, Lala Daulat Rai died so three other officers were hired to finish the land documentation work.[4] Bikram Singh also carried-out judicial reforms, with him establishing both civil and criminal courts, with him appointing retired British officials.[4] It was during Bikram Singh's reign in 1884 that the Indian railway was extended to connect with Faridkot, linking the city with Lahore, Kotkapura, Sarsa, Hisar, Revari, and Mumbai by rail.[4]

Bikram Singh was one of the founders of the Amritsar Singh Sabha organization in 1873.[4] Bikram Singh took an interest in educational pursuits, with him sponsoring the construction of schools.[4] In 1875, he was one of the founders of Mohindra College in Patiala, he had assisted the construction efforts of the college.[4] Whilst Bikram Singh's father, Wazir Singh, had divided the dominion into four administrative divisions, Bikram Singh reformed this to only be two divisions.[4] Deep Singh Wala division was absorbed into Faridkot division whilst Bhagta division was combined into Kotkapura division.[4] Chunkis were established in the former Deep Singh Wala and Bhagta divisions instead of police stations.[4]

Bikram Singh was the sponsor of the Faridkot Tika, a full commentary of the Guru Granth Sahib.[note 1][9] The idea of compiling an authoritative commentary (teeka) of the entire Guru Granth Sahib arose in-response to the insulting partial translation of the Sikh scripture by Ernest Trumpp in 1877.[9] In the same year, Bikram Singh commissioned Giani Badan Singh Sekhvan to carry-out the work of creating the commentary.[9] However, the work took a longer time than initially anticipated due to the arduous nature of the task but three volumes of the Faridkot Tika was published between 1905 and 1906, being the first published commentary of the Guru Granth Sahib.[9] Later-on, a fourth and fifth volume of the Faridkot Tika was published.[9] However, the Faridkot Tika was soon overshadowed by later Sikh exegetical works on the primary scripture, never gaining pre-eminence.[9]

In 1878, Bikram Singh assisted the British during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, with him sending troops.[4] Due to this, the British awarded Bikram Singh with the Farzandeshaadat Nishan Hazrat-e-Kesar-e-Hind title.[4] The Illustrated Weekly of India, page no. 12 reported that when Duleep Singh departed from England en route for India on 31 March 1886, he was stopped at a port in Aden and the British did not allow him to continue on-wards to India.[4] In-response, Duleep Singh dispatched secret letters to the rulers of Awadh, Gwalior, Kashmir, and other local rulers.[4] Bikram Singh of Faridkot and Hira Singh of Nabha pledged their full-support for Duleep Singh in-response.[4]

Bikram Singh died in 1898 after over 24 years on the throne.[4] He was succeeded by his son Balbir Singh.[4]

Under Balbir Singh

Raja Balbir Singh (r. 1898–1906) was the successor of Bikram Singh.[6][4] Balbir Singh had been born in 1869 and was given a high-quality upbringing by his father.[4] In 1879, his education was expanded to include the learning of Persian and English.[4] Balbir Singh befriended Babu Amarnath, who helped him with learning English.[4] Balbir carried-out his higher-level studies at Mayo College in Ajmer.[4] In 1885, while still a student at the college, Balbir got married, which was an expensive ceremony.[4] Balbir Singh married the daughter of Raja Bhagwan Singh of Manimajra State.[4] The wedding took place in Ambala district.[4]

After graduating from college, Balbir Singh delved into statecraft within the polity, developing his future ruling capabilities.[4] Balbir Singh asceded to the Faridkot throne in 1898.[4] Before his passing, Balbir's father Bikram Singh had given his younger son Dhaane in Hisar district.[4] Balbir Singh was fond of his younger brother, who was named Rajinder Singh, but Rajinder would die at the young age of 21 in 1900.[4] A while after his ascension, Balbir decided to tour his state to personally find out the problems of the local inhabitants of his dominion so he could come-up with solutions to their problems.[4]

In a book written by Balbir Singh after his tour of his kingdom, he stated the following in the introductory section:[4]

"Whenever a king takes a tour of his kingdom, his aim should be the welfare of the nation as well as that of the population."

— Balbir Singh of Faridkot State

As per the traditions of the state, during the Dussehra celebrations, a durbar (court) would be held at Faridkot.[4] In the 3 October 1900 event of the Dussehra court session at Faridkot, which was Balbir Singh's first session, two addresses had been given by the state officials and the subjects to the state government and the answers Balbir offered in-response are as follows:[4]

"… you should have by the short duration of my rule that according to my principles, no innocent person would be criminalized. I believe in trusting a suspicious person to the point until he is able not to prove himself as an innocent man. In reward for good services, I believe in promoting the person to the next level. You should believe that the service of a worker is acceptable to the point when he is able to offer his services along with believing in the Waheguru and having no other ill thoughts." ... "you have mentioned my ancestors. And this is even more commendable. The wise men say that a good ruler is one who accepts his responsibility. There is no ambiguity in this fact that those ancestors would understand their responsibilities clearly and only then could make efforts to fulfill them. They truly were in love with humanity. They were a mine of gold and every person participates according to his destiny. He feels sad in the sadness of the community and finds himself happier in the happiness of the people."

— Balbir Singh of Faridkot State, official address at the 3 October 1900 Dussehra court session at Faridkot

Furthermore, Balbir Singh discussed animals during his speech and made an announcement that additional mandis would be established.[4]

Balbir Singh was a Europhile and had a strong interest in architecture, with him constructing three gothic-style structures in the state before 1902.[6][4] Some of the buildings constructed under his watch include the Raj Mahal, Victoria Memorial, Ghanta Ghar, and the Anglo Vernacular Middle School in Faridkot.[4] One of the buildings constructed, the Raj Mahal, became the new residence for the royal family.[10] Prior to the construction of the Raj Mahal, the Faridkot royal family resided in the Faridkot Fort.[10] There exists an oil painting of Balbir Singh, whom is dressed completely in European dress in it.[6] Balbir Singh was an avid reader and writer, he founded a printing press for the state, called the Balbir Press.[10][4] Some of the books published by his printing press include the travelogue of the Maharaja of Kapurthala State and the diary of the Maharani of Kapurthala State.[4] In December 1902, the court history of the state, the Aina-i Brar Bans, was published.[6] Balbir Singh also opened a public library that contained 2,000 books from fictional and factual genres (including works on subjects like law, history, science, and religion).[10]

Balbir Singh died in February 1906 at the age of 37.[4] Balbir Singh had no issue so the throne passed onto the late Rajinder Singh's son, Brij Indar Singh.[4][6]

Under Brij Indar Singh

Balbir Singh was followed by Raja Brij Indar Singh (r. 1906–18).[note 2][6][4]

Brij Indar Singh was only 10-years-old when he came to the throne, thus state affairs were controlled by a council of regency between 1906 and 1916 during the childhood rule of Brij Indar Singh.[6][4] The council of regency was headed by Sardar Bahadur Rasaldar Partap Singh until 1909, thereafter the council was headed by Dayal Singh Maan until 1914.[4] During the rule of the council, many forward-thinking changes were implemented within the polity, such as new schemes, the construction of buildings (such as schools, hospitals, and police stations).[4] Queen Suraj Kaur Hospital for women was constructed during the rule of the council, as was the Barjindra High School.[4] During Dayal Singh Maan's tenure as head of the council, a documentation project of the state was carried-out again.[4] A new piece of legislation, called the Panchayat Act, was enacted at the time.[4]

After 1914, the council was abolished and a superintendent was appointed in its place.[4] The late ruler Balbir Singh had ensured that Brij Indar Singh was given a good education, with his English studies being under the purview of E. S. Atkinson whilst his religious instruction was taught by sardar Inder Singh of Amritsar.[4] Brij Indar Singh's higher education was done at Aitchison College in Lahore, where he earned a diploma degree in 1914.[4] Eventually, full control and power was given to Brij Indar Singh in November 1916 when he came of age.[4] Brij Indar Singh was married to the daughter of a rich man named Jeevan Singh, who came from a well-regarded and well-to-do Punjabi family that claimed a familial association with a famous Sikh martyr, Baba Deep Singh.[4] The wedding occurred at Shahzadpur.[4] This marriage produced a son named Harinder Singh.[4] Brij Indar Singh was a devout Sikh.[4] During World War I, he provided monetary assistance, supplies (such as high-quality horses and camels), and troops to the British cause on different occasions over a period of three years.[4] Up to 1 lakh rupees was given to the British for the war cause by Faridkot State.[4] Many of the soldiers who fought on the side of the British forces during the war were young men who came from Faridkot State.[4] Some of these Faridkot-origin soldiers in the war gained high-distinction, such as the case of 21 jawaans of the dominion whom were given state honours.[4] As a reward for Brij Indar Singh's efforts during the First World War, the British awarded him with the maharaja title.[4]

Brij Indar Singh had a short reign after he was given full control, dying on 22 October 1918.[4] He was succeeded by his son, Harinder Singh.[4]

Under Harinder Singh

Raja Harinder Singh (r. 1918–48) was the successor of Raja Brij Indar Singh.[note 3][6][4] He would be the last ruler of Faridkot State.[4]

Harinder Singh was born on 29 January 1915.[4] Similar to Brij Indar Singh, Harinder Singh was also a child when they ascended to the throne, thus state affairs were controlled by the council of administration between 1918 and 1934 during the childhood rule of Harinder Singh.[6][4] At the age of eight, Harinder Singh had to travel abroad for treatment due to a medical complication.[4] Harinder Singh return to Faridkot from abroad in February 1924.[4] Harinder Singh completed his higher-education at Chief's College, where he achieved high-grades on examinations.[4] Due to his good test scores, Harinder was awarded Watson-Albel Singh Medal and the Gardley Medal.[4]

Harinder Singh married the daughter of sardar Bhagwant Singh of Bhareli Estate (jagir) in the Ambala district in 1933.[4] The couple would later have one son and three daughters, with their names being Harmohinder Singh, Amrit Kaur, Deepinder Kaur, and Maheepinder Kaur.[4] Harinder took full-control over Faridkot from the council of administrative in November 1834 when he reached adulthood.[4] Much like his predecessors before him, Harinder Singh understood the value of education and therefore also opened new schools and colleges within the state, doing-so on an annual basis.[4] At the time of Harinder Singh's ascension to the throne, there was only one high-school, five middle-schools, and 47 primary-schools within the state.[4] Some of the places and programmes of education established under the purview of Harinder Singh includes Science College, B. T. Training Centre, agricultural classes, Bikram College of Commerce, J. V. Training College, and twelve high-schools and several primary-schools.[4] Under Harinder Singh, a veterinary hospital and dispensaries were opened in Faridkot city.[4] Additionally, Harinder Singh invested into roadbuilding, so the local people could travel to the mandis more easily.[4] Wells were also constructed during his reign.[4] In 1934, Harinder Singh established a secretariat that made all the offices of the state come under the courts, with a high-court being established.[4] Furthermore, a judicial committee was founded that consisted of appointed judges.[4] These reforms improved the law-and-order situation of the state.[4] There were 344 soldiers and 224 police officers in the state during the reign of Harinder Singh.[4]

Some of the titles rewarded to Harinder Singh by the British or that he had adopted by himself include: His Highness Farzande, Siyaasat Nishan Hazrat-e-Kesar-e-Hind, Brar Vansh Raja, Harinder Singh Sahib, Bahadur Ruler Faridkot, amid others.[4]

During the Indian independence movement led by the Congress, Akali Dal, and Ghadar parties, the movement was attaining a following within Faridkot State.[4] A Praja Mandal movement was launched against the Patiala State rulers, with a Mandal Committee being organized after that held regular meetings on important matters.[4] Proponents of the independence movement were tortured by the police of Faridkot State.[4] Also, the local farmers of Faridkot State were banned from selling their produce at other mandis.[4] The landlord class was heavily exploited by the state despite the state's rich treasury.[4] Also, the cost for attending educational institutions within the state was high.[4] Due to these factors, a Praja Mandal struggle took-place in Faridkot State as well.[4]

Post-independence

Faridkot State was merged into P.E.P.S.U. (Patiala and East Punjab States Union) on 20 August 1948.[5][4] Five princely states of Punjab, namely Faridkot, Patiala, Jind, Nabha, and Kapurthala states, were combined into PEPSU at this time and were disintegrated as independent dominions.[4] Then-ruling Harinder Singh was allowed to retain control over some of his assets, including hundreds of acres of land, forts, buildings, aircraft, vintage cars, and bank money, with these assets being dispersed in Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, and Delhi.[3] Harinder Singh contributed to the development of the region by constructing railways and hospitals.[3]

After the dissolution of Faridkot State, the royal family moved to Shimla for several years.[4] Harinder Singh died on 16 October 1989.[4]

Harinder Singh had four children, consisting of one son and three daughters.[3] Harinder had a falling-out with his eldest daughter Amrit Kaur due to her marrying against his wishes.[3] Two of Harinder's children, Harmohinder Singh and Maheepinder Kaur, died without leaving an heir.[3] Harmohinder Singh had died in 1981 in a car accident.[3][11] Harinder Singh later reconciled with his daughter Amrit Kaur before his death.[3]

After the death of the last ruler of Faridkot State, Harinder Singh, in 1989, his will was disputed by his surviving daughter Amrit Kaur, leading to a long court case.[3] The court ruled that a will claimed to be of Harinder Singh had been a fabrication.[3] Maheepinder Kaur died in 2001.[11]

In 2010, an 1885 oil painting of Balbir Singh kept in the Lal Kothi was stolen.[12] The stolen painting was allegedly sold in London for Rs. 35 lakh.[12]

Demographics

| Religious group |

1881[13][14][15] | 1891[16] | 1901[17] | 1911[18][19] | 1921[20] | 1931[21] | 1941[22] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Sikhism |

40,187 | 41.42% | 47,164 | 41% | 52,721 | 42.21% | 55,397 | 42.52% | 66,658 | 44.24% | 92,880 | 56.51% | 115,070 | 57.74% |

| Islam |

29,035 | 29.92% | 34,376 | 29.88% | 35,996 | 28.82% | 37,105 | 28.48% | 44,813 | 29.74% | 49,912 | 30.37% | 61,352 | 30.79% |

| Hinduism |

27,463 | 28.3% | 33,079 | 28.75% | 35,778 | 28.64% | 37,377 | 28.69% | 38,610 | 25.63% | 20,855 | 12.69% | 21,814 | 10.95% |

| Jainism |

349 | 0.36% | 408 | 0.35% | 406 | 0.33% | 409 | 0.31% | 473 | 0.31% | 550 | 0.33% | 800 | 0.4% |

| Christianity |

0 | 0% | 13 | 0.01% | 11 | 0.01% | 6 | 0% | 107 | 0.07% | 167 | 0.1% | 247 | 0.12% |

| Zoroastrianism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Buddhism |

0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Judaism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Total population | 97,034 | 100% | 115,040 | 100% | 124,912 | 100% | 130,294 | 100% | 150,661 | 100% | 164,364 | 100% | 199,283 | 100% |

| Note: British Punjab province era district borders are not an exact match in the present-day due to various bifurcations to district borders — which since created new districts — throughout the historic Punjab Province region during the post-independence era that have taken into account population increases. | ||||||||||||||

Transportation

In 1884, the metre-gauge North-Western Railway line connected the towns of Faridkot and Kot-Kapura with Lahore and with Delhi via Bathinda, Sirsa, Hissar, and Rewari.[6]

Economy

The annual state income of Faridkot was small.[6] The main sources of revenue for the state was sourced from agriculture.[6] Agriculture within the state relied upon rain water, as the region was arid.[6] However, in 1885, the British constructed a branch of the Sirhind Canal, sourcing its water from the Sutlej river, to provide irrigation to the farms of Faridkot State, which helped improved the advancement of agriculture in the state.[6] Trade in the state was boosted in 1884 with the connection of a railway line to Faridkot and Kot-Kapura with other regions of India.[6]

Architecture

With the improvement of the state's funds due to the advancements made in agriculture and trade, the rulers were able to dedicate funds to the construction of architectural projects.[6] The rulers of Faridkot State constructed many gothic-style buildings in their erstwhile state, due to the influence of the British and the gothic revival.[6] Gothic architecture reached Faridkot through the railway, commencing in 1884.[6] The gothic style incorporated indigenous elements.[6] Balbir Singh constructed three gothic-styled buildings: the Raj Mahal, the Victoria Clock Tower, and Kothi Darbarganj, with all of them being built before 1902.[6][10] The gothic-style clock tower was erected in 1901 in-memory of Queen Victoria who had died on 22 January the same year.[23] The gothic-style fell into decline due to the introduction of new building materials and techniques.[10] Architectural activity in the erstwhile state continued all the way up until its accession in 1948.[6]

List of rulers

| No. | Name

(Birth–Death) |

Portrait | Reign | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sardars[note 4] | ||||

| 1 | Hamir Singh

(1731–1782) |

1763 – 1782 | [2][5] | |

| 2 | Mohar Singh | 1782 – 1798 | [5] | |

| 3 | Charat Singh | 1798 – 1804 | [5] | |

| 4 | Dal Singh | 1804 | [5] | |

| 5 | Gulab Singh | 1804 – 1826[note 5] | [5][2][4][7] | |

| 6 | Attar Singh | 1826 – 1827 | [5][2][7] | |

| 7 | Pahar Singh |

|

1827 – 1846 | [5][7] |

| Rajas[note 6] | ||||

| 7 | Pahar Singh

(1799 – April 1849) |

|

1846 – 1849 | [5][4][7] |

| 8 | Wazir Singh |

|

1849 – 1874 | [5] |

| 9 | Bikram Singh

(1843–1898) |

|

1874 – 1898 | [5] |

| 10 | Balbir Singh

(died 1906) |

|

1898 – 1906 | [5] |

| 11 | Brij Indar Singh |

|

11 November 1906 – 1918 | [5] |

| 12 | Harinder Singh | 1918 – 1948 | [5] | |

| Faridkot State was merged into P.E.P.S.U. on 20 August 1948[5] | ||||

Gallery

- Fresco of Guru Nanak, Bhai Mardana, and Bhai Bala located in the Sheesh Mahal of Faridkot Fort

- Sanad document of investiture of Raja Pahar Singh of Faridkot State from the British East India Company

- Seal of Bikram Singh of Faridkot State, 1878

- Photograph of a group of state officials of Faridkot State

- Photograph of the Raj Mahal palace of Faridkot State

- Photograph of the Mubarak Mahal palace of Faridkot State

- Photograph of an avenue in the Darbar Ganj Gardens of Faridkot State

See also

Notes

- ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

- ^ 'Tika' is alternatively spelt as 'Teeka'.

- ^ Brij Indar Singh's personal name is alternatively spelt as 'Brijinder' or 'Barjinder'.

- ^ Harinder Singh's personal name is alternatively spelt as 'Harindar'.

- ^ Chiefs

- ^ Interlude between 1807–1809 due to the occupation of Faridkot by the Lahore State.

- ^ Pahar Singh was bestowed with the title of raja in 1846.

References

- ^ a b Arora, A. C. (1982). British Policy Towards the Punjab States, 1858–1905. Export India Publications. p. 349. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Singh, Gursharan (1991). History of Pepsu: Patiala and East Punjab States Union, 1948-1956. Konark Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 9788122002447.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chhabra, Arvind (30 September 2022). "Faridkot: An Indian maharaja and a 'mystery' will". BBC. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec ed ee ef eg eh ei ej ek el em en eo ep eq er es et eu ev ew ex ey ez fa fb fc fd fe ff fg fh Singh, Sukhpreet; Bhullar, Sukhjeet Kaur (2019). "Contributions of Different Kings in the Faridkot State". Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 10 (1): 248–252. doi:10.5958/2321-5828.2019.00045.7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Truhart, Peter (2017). Regents of Nations: Asia, Australia-Oceania, Part 2 (Reprint ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 1395. ISBN 9783111616254.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Parihar, Subhas (11 February 2012). "The Sikh Kingdom of Faridkot". sikhchic. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Singh, Fauja; Rabra, R. C. (1976). The City of Faridkot: Past and Present. Punjabi University. pp. 24–26.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Faridkot". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f Fenech, Louis E.; McLeod, W. H. (11 June 2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 112. ISBN 9781442236011.

- ^ a b c d e f Parihar, Subhas (12 February 2012). "The Gothic Palaces of Faridkot". sikhchic. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b Kamal, Neel (1 October 2023). "Year after SC order, royal property split in limbo". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Missing 1885 painting of Faridkot Sikh ruler ends up in auction in UK". Sikh Sangat News. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. I." 1881. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057656. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. II". 1881. p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057657. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. III". 1881. p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057658. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "The Punjab and its feudatories, part II--Imperial Tables and Supplementary Returns for the British Territory". 1891. p. 14. JSTOR saoa.crl.25318669. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. [Vol. 17A]. Imperial tables, I–VIII, X–XV, XVII and XVIII for the Punjab, with the native states under the political control of the Punjab Government, and for the North-west Frontier Province". 1901. p. 34. JSTOR saoa.crl.25363739. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 14, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. p. 27. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393788. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Kaul, Harikishan (1911). "Census Of India 1911 Punjab Vol XIV Part II". p. 27. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 15, Punjab and Delhi. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. p. 29. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430165. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1931. Vol. 17, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1931. p. 277. JSTOR saoa.crl.25793242. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ India Census Commissioner (1941). "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 6, Punjab". p. 42. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215541. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Parihar, Subhash. "Gothic Revival at Faridkot". Academy of the Punjab in North America. Retrieved 7 August 2024.