False door

A false door, or recessed niche,[1] is an artistic representation of a door which does not function like a real door. They can be carved in a wall or painted on it. They are a common architectural element in the tombs of ancient Egypt, but appeared possibly earlier in some Pre-Nuragic Sardinian tombs known as Domus de Janas. Later they also occur in Etruscan tombs and in the time of ancient Rome they were used in the interiors of both houses and tombs.

Mesopotamian origin

Egyptian architecture was influenced by Mesopotamian precedents, as it adopted elements of Mesopotamian Temple and civic architecture.[3] These exchanges were part of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations since the 4th millennium BCE.[3]

Recessed niches were characteristic of Mesopotamian Temple architecture, and were adopted in Egyptian architecture, especially for the design of Mastaba tombs, during the First Dynasty and the Second Dynasty, from the time of the Naqada III period (circa 3000 BCE).[3][4] It is unknown if the transfer of this design was the result of Mesopotamian workmen in Egypt, or if temple designs appearing on imported Mesopotamian seals may have been a sufficient source of inspiration for Egyptian architects.[3]

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians believed that the false door was a threshold between the worlds of the living and the dead and through which a deity or the spirit of the deceased could enter and exit.[5]

The false door was usually the focus of a tomb's offering chapel, where family members could place offerings for the deceased on a special offering slab placed in front of the door.[6]

Most false doors are found on the west wall of a funerary chapel or offering chamber because the Ancient Egyptians associated the west with the land of the dead. In many mastabas, both husband and wife buried within have their own false door.

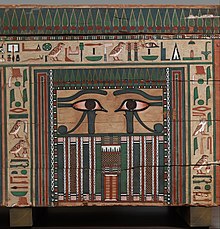

Structure

A false door usually is carved from a single block of stone or plank of wood, and it was not meant to function as a normal door. Located in the center of the door is a flat panel, or niche, around which several pairs of door jambs are arranged—some convey the illusion of depth and a series of frames, a foyer, or a passageway. A semi-cylindrical drum, carved directly above the central panel, was used in imitation of the reed-mat that was used to close real doors.

The door is framed with a series of moldings and lintels as well, and an offering scene depicting the deceased in front of a table of offerings usually is carved above the center of the door.[5] Sometimes, the owners of the tomb had statues carved in their image placed into the central niche of the false door.

Historical development

The configuration of the false door, with its nested series of doorjambs, is derived from the niched palace façade and its related slab stela, which became a common architectural motif in the early Dynastic period. The false door was used first in the mastabas of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (c. 27th century BCE) and its use became nearly universal in tombs of the fourth through sixth dynasties.[7] Rarely, the Old Kingdom false door was combined with statues, demonstrating the common ancestry of the false door and naos in similar early ancient Egyptian architectural features.[8] During the nearly one hundred and fifty years spanning the reigns of the sixth Dynasty pharaohs Pepi I, Merenre, and Pepi II, the false door motif went through a sequential series of changes affecting the layout of the panels, allowing historians to date tombs based on which style of false door was used.[9][10]: 808 The same dating approach is used also for the First Intermediate Period.[11]

After the First Intermediate Period, the popularity of the false doors diminished, being replaced by stelae as the primary surfaces for writing funerary inscriptions.[10]: 808

Representations of false doors also appeared on Middle Kingdom coffins such as the Coffin of Nakhtkhnum (MET 15.2.2a, b) dating to late Dynasty 12 (c. 1850–1750 BCE).[12] Here, the false door is represented by two wooden doors that are secured with door bolts, bracketed on both sides by architectural niching – recalling earlier niched temple and palace façades such as the enclosure wall that surrounds the mortuary complex of king Djoser of the Third Dynasty. In a similar manner to the Old Kingdom false doors, representations of false doors on Middle Kingdom coffins facilitated the movement of the deceased's spirit between the afterlife and the world of the living.[13]

Inscriptions

The side panels usually are covered in inscriptions naming the deceased along with their titles, and a series of standardized offering formulas. These texts extol the virtues of the deceased and express positive wishes for the afterlife.

For example, the false door of Ankhires reads:[14]

The scribe of the house of the god's documents, the stolist of Anubis, follower of the great one, follower of Tjentet, Ankhires.

The lintel reads:

His eldest son it was, the lector priest Medunefer, who made this for him.

The left and right outer jambs read:

An offering which the king and which Anubis,

who dwells in the divine tent-shrine, give for burial in the west,

having grown old most perfectly.

His eldest son it was, the lector priest Medunefer,

who acted on his behalf when he was buried in the necropolis.

The scribe of the house of the god's documents, Ankhires.

Prehistoric Sardinia

Carved or painted Pre-Nuragic false doors appear in about 20 tombs mostly located in northwestern Sardinia,[16]: 137–139 an example being some of the Domus de Janas of the necropolis of Anghelu Ruju, which are variously datable from the Ozieri to the Bonnanaro cultures of Pre-Nuragic Sardinia (c. 3200 – c. 1600 BCE).[17]

These false doors, apparently resulting from a strong Eastern influence,[17]: 11 usually appear on the back wall of the main chamber, and are represented by horizontal and vertical frames and a projecting lintel.[16]: 137–139 Sometimes the door is topped with painted or carved U-shaped bull horns, inscribed inside each other in a variable number.[16]: 144 [15]

Unlike the Egyptian ones, the meaning of pre-Nuragic false doors is less clear. It has been argued that these represents the passageway to the afterlife that definitively separate the deceased from the living loved ones, also preventing a possible return.[16]: 137–139 Alternatively, it is possible that these false doors are simply clues of the plan of the corresponding former house of the deceased.[18]: 44

Etruria

In Etruscan tombs the false door has a Doric design and is always depicted closed. Most often it is painted, but on some occasions it is carved in relief, like in the Tomb of the Charontes at Tarquinia. Unlike the false door in ancient Egyptian tombs, the Etruscan false door has given rise to a diversity of interpretations. It might have been the door to the underworld, similar to its use of the ancient Egypt. It could have been used to mark the place where a new doorway and chamber would be carved for future expansion of the tomb. Another possibility is that it is the door of the tomb itself, as seen from outside. In the Tomb of the Augurs at Tarquinia two men are painted to the left and right of a false door. Their gestures of lamentation indicate that the deceased were considered to be behind the door.[19]

Ancient Rome

Painted doors were used frequently in the decoration of both First- and Second style interiors of Roman villas.

An example is the villa of Julius Polybius in Pompeii, where a false door is painted on a wall opposite a real door to achieve symmetry. Apart from creating architectural balance, they could serve to make the villa seem larger than it really was.[20]

See also

References

- ^ "The term false door (also ka-door, false- door stela, fausse-porte, Scheintiir) denotes an architectural element that is found mostly in private tomb structures of the Old Kingdom (mastabas and rock-cut tombs): a recessed niche, either in the western wall of the offering chamber, or in the eastern tomb facade. It imitates the most important parts of an Egyptian door, but the niche offers no real entrance to any interior space. Such fictitious doors are also attested in other architectural contexts" in Redford, Donald B. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt: A-F. Oxford University Press. p. 498. ISBN 978-0195138214.

- ^ Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0292752429.

- ^ a b c d Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 71. ISBN 978-1444342345.

Nancy H. Demand is Professor Emerita in the Department of History, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. - ^ Silberman, Neil Asher (2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0199735785.

- ^ a b Bard, KA (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. NY, NY: Routledge.

- ^ Allen, JP (2000). Middle Egyptian. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 95.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (2010). "Mortuary Architecture and Decorative Systems". In Lloyd, Alan (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 808. doi:10.1002/9781444320053.ch36. ISBN 978-1405155984.

Private tombs of the Third Dynasty [c. 2686 BC–2613 BC] broadly followed the pattern of those of the Second, in being brick mastabas. However, there were significant developments in the form of the offering place at the southern end of the eastern facade, which was in some cases lined with stone and projected into the heart of the mastaba. These linings could be decorated, while a niche at the northern end of the tomb might be dedicated to the cult of the wife of the tomb owner. The southern niche and its slab-stela evolved during the Third Dynasty into what by the following dynasty had become the classic false door.

- ^ Odler, Martin; Peterková Hlouchová, Marie; Dulíková, Veronika (2021). "A unique piece of Old Kingdom art: the Funerary Stela of Sekhemka and Henutsen from Abusir South". Ägypten und Levante (in German). 31: 403–424. doi:10.1553/AEundL31s403. ISSN 1015-5104. S2CID 245576259.

- ^ Strudwick, Nigel (1986). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom. Kegan Paul.

- ^ a b Dodson, Aidan (2010). "Mortuary Architecture and Decorative Systems". In Lloyd, Alan (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405155984.

- ^ Pitkin, Melanie (2023). Egypt in the First Intermediate Period: The History and Chronology of its False Doors and Stelae (1 ed.). London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 9781906137816.

- ^ "Coffin of Khnumnakht". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2015). Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kei (eds.). Coffin of Khnumnahkt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 232–233, no. 169.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Brill. p. 239.

- ^ a b Monte Siseri o S'Incantu – Putifigari. neroargento.com

- ^ a b c d Contu, Ercole (2006). La Sardegna preistorica e nuragica. Volume 1: la Sardegna prima dei nuraghi [Prehistoric and Nuragic Sardinia. Volume 1: Sardinia before the nuraghi] (in Italian). Carlo Delfino editore. ISBN 8871384210.

- ^ a b Demartis, Giovanni Maria (1986). La Necròpoli di Anghelu Ruju. Sardegna Archeologica 2. Carlo Delfino editore.

- ^ Tanda, Giuseppa (1985). L'Arte delle domus de janas nelle immagini di Jngeborg Mangold: Palazzo della provincia, 26 aprile-25 maggio 1985 (in Italian). Sassari, Amministrazione provinciale.

- ^ Jannot, Jean-René (2005). Religion In Ancient Etruria. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0299208448.

- ^ Clarke, John R. (1991). The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-0520084292.

Further reading

- Owen, Maurice (24 February 2010). "False – Doors". The False-Door : dissolution and becoming in Roman wall-painting. Southampton Solent University. Retrieved 28 July 2013.