Emathia

Ἠμαθία Emathia | |

|---|---|

| Native language | ancient Macedonian |

| Type | Absolute monarchy |

Emathia (Greek: Ἠμαθία) in ancient times was a geopolitical toponym, although no doubt based on a type of terrain prevalent in the region at the time. The toponym comprised different territories at different times, expanding from a base in the lower Axios River valley to include all of what was renamed to Macedonia.

Emathia initially was the region of the Macedonian capital, Pella, also of the capital of the Macedonian League, Beroia. In portraying these poleis moderns often based and still base their conclusions upon the modern map. Core samples and radiocarbon dating confirm that 19th and early 20th century literary analyses often had not taken into consideration changes in the terrain and the latest available archaeological data. Pella was not a late classical or Hellenistic settlement, although rendered into a legitimate polis by Philip II. Mycenaean surface sherds support at least a Bronze-age provenience, or close to it.

Moreover, Pella until quite late in the classical period had been a port city of the Thermaic Gulf. Subsequently, its estuary became a lake until it was dispensed with by agriculturalists of the 20th century, with the Loudias River as a remnant. Consequently, the courses of modern rivers there, as well as the alluvial area, now called "the Central Macedonian Plain," are modern and cannot be used to elucidate the details presented by the literary sources.

Today most of the C. Macedonian Plain is occupied by the Axios Delta National Park, mainly a collection of wetlands. Modern Imathia, etymologically from the same ancient word, is a new creation of modern Greece, as is modern Macedonia.

Localization

History of the terrain

Subsidence and aggradation in the region

The Aegean Sea Plate undergoing subsidence because of back-arc extension behind the Hellenic arc, the Aegean Sea is a classic example of drowned terrain: islands fronted by steep cliffs formed from mountain-tops, submergent coastlines with long estuaries formed by flooding from the sea. Acting contrary to the submergence is aggradation. Drowned rivers dump their sediment into their new estuaries creating river deltas. The deltas eventually combine to form alluvuial shelves and valleys, which, in the Aegean, typically became agricultural areas.

Over any period, an aggraded shoreline is the result of an equilibrium between subsidence and aggradation. Subsidence pushed the coastline inland; aggradation brings it out. The equilibrium may be cyclical, or it may trend in one direction.

Core studies in the C. Macedonian Plain compared with core studies from the whole Mediterranean have established that throughout the Aegean the rate of subsidence is on the average a little less than a metre per thousand years, which expresses itself as a rise in sea level to an observer at the surface.[1][a] Bintliff calls this a "eustatic rise."[b]

The shoreline at any isochrone; that is a line on the basin wall every part of which has the same date, obviously depends on the configuration of the surface between the location of the foot of the core and the concurrent shoreline. The more core samples that are available, the better the geologist can detail the surface. All models retain an element of speculation. In the case of the C. Macedonian Plain, Bintliff combines geological data with historical sources to develop a brief history of shorelines there.

On the map, the Plain is the green area at the mouth of the Axios River. Stretching across the Axios, it extends E-W from Thessaloniki to Naoussa, a distance of about 73.42 km (45.62 mi), and N-S from Giannitsa to Vergina, about 34.53 km (21.46 mi). This is approximately the location of modern Imathia. The latter country, however, is distinguished from the ancient by not having been there. In its place was either a shallow estuary of the Thermaic Gulf, or a lake in a marsh, from prehistoric times to nearly the present. Ancient Emathia can only have been further north, but of course at the time when the name was changed, Emathia was all of Macedonia.

The white clay marker layer

Geologists of the 19th and 20th centuries formulated a number of geologic models of the central Macedonian plain, but few were as useful those based on the excavation of Nea Nikomedeia (NN), 1961, 1963–64, under the direction of Rodden and Grahame Clark.[2] NN is a Neolithic site at 40°36′15″N 22°15′54″E / 40.604156°N 22.264982°E, within the borders of Veria (Beroia), ancient capital of the Macedonian League, at the SW edge of the Plain.[c]

The mound of NN rose to a height of 3.5 m (11 ft) over an undisturbed subsoil layer of "white carbonate silt," with a disturbed layer over the undisturbed layer of 0.5 m (1.6 ft).[3] The silt was classified by the excavators as lacustrine.[4] It was pollen-free.[5] Although it had accumulated under a lake, it was high and dry at least at that location when the first Neolithic settlers built their village upon it.[6]

This same layer was found at the bottom of an excavated drainage ditch 100 m to the SW, the layer's top surface being at 6 m above current sea level (asl).[3] NN seems to have been constructed on a mound of it. The layer in the ditch, however, represents ground level.

In 1965 a core, subsequently named GIANNITB, taken by Sytze Bottema from the central area of the alluvium 7.5 km (4.7 mi) to the NW along a line to Gianitsa,[d] revealed a physically similar white clay layer, believed to be of the same surface. This white layer occupied the 13th meter of the core, with a nominal depth of 12.52 m, a top surface of 12.39 m, and a bottom surface of 12.65 m, which was the very last of the core. It is described as consisting of "light-grey, marly clay."[7] A meter of the core should not be confused with a meter of sea level. In this case the core began at 1 m asl, so its 13th m of the core was 12 m bsl (below sea level).[5][e]

Subsequently, the white layer began to turn up in other cores and at other locations around the Macedonian Plain. It was clear that at some geologic time prior to the Neolithic the white layer had been deposited at the bottom of a lake and that it was continuous. Subsequently, subsidence dropped the greater part of the bottom, which then alluviated. The edges, such as NN, having been found at the surface, can be presumed not to have dropped.[8][f] The difference in altitude between the exposed settlement layer at NN and the bottom of the core is calculated at 7.5 m asl + 12 m bsl = 19.5 m (64 ft).

The marker layer can be used to determine dates and depths as well as the general type of terrain. Typically the data is presented in a graph of sea level depth in m on the y-axis and numbers of millennia on the x-axis. Thus the slope at any point is a rate, m/mill., called the rate of aggradation. It is also the rate of subsidence, as aggradation cannot occur without subsidence. The meters do not distinguish between the two. A high slope is a rapid rate; a low slope is a low rate.

The calibration problem

All measurement devices must undergo a finalization procedure in their manufacture called calibration. The device is designed to generate a number that is quantitatively proportional to a value of the natural variable being measured. However, due to accidental factors not understood the readings may differ from the true values by logically consistent amounts. The application of consistent corrections is the calibration. To determine the amount of the correction the calibrator arbitrarily adjusts the readings to conform to test points known to be true. Of course, the more test points in calibration, the more confidence one can have that the readings are accurate.

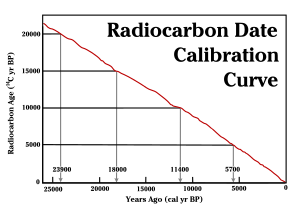

In archaeology a suitable biomass (such as wood) can be dated by radiocarbon dating, or C-14 dating. It is based on the fact that the atmosphere contains a certain proportion of the radioactive isotope of C, Carbon-14, which it passes on to living biomasses through regular chemical interchange and reaction, which ceases on the death of the biomass. Due to regular radioactive decay the amount of the now isolated isotope depends on the time since the cessation of interchange. Laboratories that do C-14 dates first determine the amount of the isotope left in the sample, expressed as a percentage of atoms, then look up the date on a chart such as that shown in the figure. The purity of the sample is of the greatest concern.

The first C-14 dates were welcomed enthusiastically. The inventor received a Nobel Prize for his work. Subsequently, more careful comparison of C-14 dates with known historical events turned up some major discrepancies. A conflict ensued over the validity of C-14 dates, especially where the dates of some of the better known historical artifacts were concerned. It was time to move on, but fortunately the discovery that the discrepancies were mainly a matter of calibration restored confidence in C-14 dating. It was possible in many cases to offset the raw, or uncalibrated dates, in such a way as to produce accurate calibrated dates. A favored method of calibration of wood samples is to compare a run of C-14 dates with dates from tree rings. The calibration curve soon made its appearance. It is a plot of uncalibrated dates on the y-axis with calibrated dates on the x-axis.[g]

The controversial calibration of GIANNITB

The worldwide graph of sea level versus millennia bp shows a slope approximating a straight line at a steep angle until about 8000 bp, when it breaks, becomes shallow, and at about 6000 bp ceases to show subsidence, except for a dampened sinusoidal curve excursing cyclically above and below sea level. This fluctuation explains why the white layer appears above sea level. Currently there is no subsidence, explaining why aggradation has the upper hand. The flood basins are all full of silt, extending the shorelines outward.[9]

There is dating available on NN.[h] The earliest settlement there, termed "the Early Neolithic" (EN), is dated 5500-5300 BC based on C-14 dates,[10] which, allowing 1950 for the AD time, would be 7450-7250 BP, the 8th millennium BP. A subsequent layer of detritus suggests an abandonment followed by a "Late Neolithic" reoccupation during which the ditch was dug.[10] The EN, being directly on the white layer, places the layer at settlement in the 8th millennium BP.

There is a problem with applying the general rate of subsidence to specific instances of subsidence, such as the white floor of the plain of Emathia. According to the general rate of 1, the whole layer should be dated to the 13 millennium BP. At NN, it is dated to the 8th. Obviously, the standard rate cannot apply to the core if the layer at both places really is the same. Further, the total displacement of 19.5 m would seem to require a time of 19.5 millennia, not 13. Obviously, no standard rates can apply.

In radiocarbon calibration curves a large number of points are usually available, often enabling the application of techniques such as curve fitting. In cores and other columns of sedimentaty layers points of known date are few and far between. The core only gives a sequence of layers associated with depths. The rates of sedimentation and the times of the layers remain to be determined. Radiocarbon dating of suitable materials in the core is still the common method of determining test points of the core. These are expensive, and must therefore be carefully selected.

Having perceived the contradiction, and realizing the need to calibrate the plot of core meters[i] versus BP dates; that is, to associate points within the plot with known data, Bottema acquired two carbon dates from material in the core, one from 6.525 m, and one from 9.950 m.[11] Very likely, both were done in the same year, 1965.

The 6.525 m date was 6590 ± 110 BP, which falls into the 6th millennium within the layer 6.58-6.8 m, described as "blue-grey clay," with an average depth of 6.69 m. The 9.950 m date was 7.27 ± 70 BP, which falls into the 8th millennium within the layer 9.74-10.91, described as "grey or blue-grey clay + shell fragments," with an average depth of 10.325 m.

Geologic history of the terrain over the white layer

Bintliff's reconstruction of the early Plain of Central Macedonia is as follows. It was not originally a plain. The orogenesis of the NW-SE trending ridges of the Hellenic Orogeny created geosynclines that became river valleys. They led from the high country of the Balkans down into a region of sub-ridges next to the Thermaic Gulf that were beginning to subside along with the rest of the floor of the Aegean. They became notches from which alluvium was eroded to be deposited into the valleys between the smaller ridges until a smooth surface covered both valleys and sub-ridges. Bintliff uses such language as "the Almopias Furrow" and "the Axios Trench."[12]

In short the plain serves as a sink for the drainage of the surrounding highlands.[13] Fortuitously it is roughly wheel-shaped with the rivers as spokes. The human settlements are where the spokes join the hub. They are some of the first settlements in Greece, dating from the Early Neolithic. A brief review follows, starting from the SW of the wheel, moving CW, and ending on the SE, with the Thermaic Gulf as the exit notch.[14]

On the SW the upper Haliacmon River drains the east slopes of Mount Pindus on the southern border of Macedonia. At points closer to the plain it flows to the north side of the Pierian Mountains, where it is dammed in a few places to impound reservoirs. The last, Haliakmon Dam, creates an artificial lake. From there it crosses the plain to the NE, being joined by its tributary, the Moglenitsas, which ends there. The Haliakmon flows from there to the gulf at Delta Aliakmona.

On the west of the plain the Vermio Mountains form a wall of hills trending NNE. They extend from the W bank of the Haliakmon northward into Almopia, being paralleled the entire distance by the Moglenitsas River. Various smaller streams drain the Vermio Mountains from west to east, becoming tributaries of the Moglenitsas.

The region derives ultimately from a calcic lake in a subsiding region during the Pliocene (5.33-2.58 Mya). The white, calcareous layer crystallized out of solution and was deposited over the bottom in a layer about 1 m thick. The phase lasted through the mid-Pleistocene (1.25-0.7 Myr).

In the Late Pleistocene (129,000-11700 ya) through the Early Holocene (11650-8200 bp), the lake dried up, exposing the white layer, from which weathering removed the pollen. This is the time when the white layer was probably continuous and simultaneous, with no detritus over it, at NN.

The prototype of the northern Thermaic Gulf

Two m of alluvium at the core, however, indicate a contemporaneous slope of the layer between NN and there. The sea level was 6–9 m bp. At the C-14 date of 7270 bp the plain would have appeared as a dry, bright surface with a mound at the future NN. There were none yet to settle it.

History of the Iron-Age wetlands

Lake Loudias

Demography

Original settlement of Macedonia proper

The Neolithic is by definition a time of agricultural settlement. Such a settlement built permanent villages in which persons lived who tilled fields they considered theirs on a permanent basis, whether privately or collectively. They also reared farm animals. The fact that they were able to grind stone tools is only incidental. They could perform a large variety of domestic arts, such as weaving, and pottery-making, that required fixed facilities. Stone, mud, wood, and thatch were the first durable materials employed.

Before the Neolithic but few sources are willing to consider any country as being settled.

The appearance of Macdonia proper in history

By the time Emathia appears in history, it is already gone. In its place stands kato Makedonia, "Lower Macedonia," as it was when it was about to be attacked by Sitalces, Thracian king of the late 5th century BC. Perdiccas II of Macedon of the Temenid Dynasty was the Macedonian king. Alexander I of Macedon, his father, "and his forefathers" had conquered Emathia earlier and had renamed it to Macedonia. These are the events described by Thucydides (Book II.99), considered their most credible narrator, because his account corresponds to that of Herodotus, their first author. Thucydides describes also Upper Macedonia (epanothen) as Macedonian also, but the original Macedon, he says, was the lower.

According to Thucydides, The Temenid Dynasty of Argos formed a new "country by the sea" by defeating tribal states arranged in a near-circle around the shores of what was then the Thermaic Gulf. It was not only near the sea, it was around it, on a strip of shoreline between the sea and the mountains. They were apparently independent as no one came to their aid, and they fell piecemeal.

The Macedonians began by attacking the Pierians of Pieria in the Pierian Mountains between the Haliakmon and Mount Olympus. They escaped by founding Piereis beyond the Strymon to the east, leaving Pieria to become the first district of Lower Macedonia. Next in order was Bottiaea. The Macedonians could not, as some modern authors suggest they might have done, follow any modern routes across the plain. There was no plain, only the Thermaic Gulf, to which access was impeded by swampland. This was a natural set-up for a victory, as only one tribal state at a time appeared before them, and there was no place where a group of them could concentrate. The Bottiaeans also were driven out. They formed the new state of Bottike on Chalcidice.

Inevitably the Macedonians reached the Paeonians, an ancient Balkan state on the Axios. All they managed to take from them was a strip of land on the right bank of the Axios, and the north shore of the gulf, including Pella. Thucydides says the purloined land extended "from the interior to Pella and the seas," which is used now to demonstrate Pella was on the gulf. On the opposite bank of the Axios was Mygdonia east to the Strymon. It was held by the Edonians. They obliged the Macedonians by escaping across the river and founding Edonis on the other side. Thus Thrace became Macedonian.

There are more tribes displaced over the Axios leaving their former districts to the Macedonians: Eordaeans, Almopians, Anthemians, Crestonians, Bisaltians, and others. Thucydides, however, raises as many questions as he answers. Hammond says, "The extraordinary thing about this account is that Thucydides does not tell us where the Macedones started from on their career of conquest."[15] If extraordinary to modern historians, it may have been well known to Thucidides' target audience. From wherever it was, there must have been a relatively major movement of people from there into Emathia. One might infer that it was not very far away. At the beginning of the passage Thucydides already hints that there are Macedonians in upper Macedonia., practically within sight of the lowland villages.

An ancient Macedonian language is known to have existed, whether a dialect of Greek (current theory) or a distinct language close to Greek. It is known from onomastic and epigraphic evidence of the 1st millennium BC. Subsequently, it disappeared in favor of koine Greek, the lingua franca of the region. Since there was a Macedonian language, Thucydides' passage implies that the change in population was also a change in language; otherwise, the displaced indigenes would have been thought Macedonian also.

As to the many tribes displaced, they must have taken their languages with them. Attempts to define these languages from epigraphy and onomastics have created a new field of study, Paleo-Balkan languages, which is not a single language group. These are believed remnants of previous successive immigrations down the Axios.

The ancient towns of Emathia

Settlements in Emathia are mainly towns of prehistoric antiquity placed around the edge of the plain, except for Nea Nikomedeia, which extended out into the plain. It was Bintliff's hypothesis that at the time ancient NN was founded, the western plain was dry. As wetlands occupied the plain from ancient to modern times, and was only recently turned to agricultural uses, there are now no cities in it.

| Name | Location | Provenience | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methone Μεθώνη |

40°28′03″N 22°35′01″E / 40.467444°N 22.583649°E. A hilly settlement overlooking the junction of the current NW Thermaic Gulf with the then wetlands to the north. Modern Methoni is just to the south. | Material has been found from every period from the Neolithic to the Ottoman Middle Ages. Pydna was in the vicinity.[16] |

|

| Veroia Βέρροια |

40°31′N 22°12′E / 40.517°N 22.200°E | ||

| Kition (modern Naoussa) | |||

| Kydrai | |||

| Aigai | |||

| Kyrrhos | |||

| Pella Πέλλα |

40°45′17″N 22°31′16″E / 40.754669°N 22.521050°E. Originally on the stony islet of Fakos at the edge of the Thermaic Gulf. Modern faki means "lentil", meaning the shape of the islet. The ancient name, Pella, means "stony." | Early Bronze Age settlement from the 3rd millennium.[17] |

|

| Ichnai | |||

| Therma |

Testimony of the sources

Earliest known name of Paeonia

Polybius (23.10.4) mentions that Emathia was earliest called Paeonia and Strabo (frg 7.38) that Paeonia was extended to Pieria and Pelagonia. According to N. G. L. Hammond,[18] the references are related to Bronze Age period before the Trojan War.

Under the name of Emathia

Homer,[19] who makes no mention of Macedonia, places Emathia as a region next to Pieria.

but Hera darted down and left the peak of Olympus; on Pieria she stepped and lovely Emathia, and sped over the snowy mountains of the Thracian horsemen, even over their topmost peaks, nor grazed she the ground with her feet; and from Athos she stepped upon the billowy sea, and so came to Lemnos, the city of godlike Thoas

The Homeric name was renewed mainly in Roman times and Ptolemy mentions some cities of Emathia. In Nonnus, Dionysiaca 48.6 Typhoeus having stripped the mountains of Emathia, he cast the rocky missiles at Dionysus. In Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.313 the daughters of Pierus say: "we grant Emathia's plains, to where uprise Paeonia's peaks of snow".[20]

The Emathian or Emathius dux is a frequently used name by Latin poets for Alexander the Great, as in Milton, the Emathian conqueror. Strabo relates that "what is now called Macedonia was in earlier times called Emathia"[21] but since Homer, the earliest source considers Emathia only a region next to Pieria, Strabo's reference should be interpreted in the Roman era context of Emathia's name reviving.[citation needed] The same stands for Latin writers[22] who name Thessaly as Emathia; the Roman province of Macedonia included Thessaly. In 12.462 of Metamorphoses, an Emathian named Halesus is killed by the centaur Latreus and in Catullus 64. 324, Peleus is Emathiae tutamen (protector).

The change to Macedonia

Probably because of its use as the name of the most powerful and most influential state of ancient Greek history, Macedon is one of the most commonly folk-etymologized and mythologized names of ancient Greek. One hears of this or that ancient hero assigning the name to a new race of warriors, perhaps "the tall men" or "the thin men." To the Romans they seemed special indeed because they would not accept Roman rule; consequently the Romans cleared them out to resettle the land with more tractable populations. The question of where the stalwart race of conquerors had actually lived went on into modern times until modern scholarship took a hand in locating them. Before then the Slavs invading Greece laid claim to the name creating a country called Macedonia, and then another, North Macedonia, despite Greek protests that Macedonia had never had a north in that location. The issue is a contentious one today (see Macedonia naming dispute).

Homer, Hesiod, and the Bronze Age

Because the Macedonian Empire was the last one of ancient Greece before the Roman Empire, Macedonia has the reputation of being late in the catalog of ancient Greek ascendencies. To the contrary, the name of Makedonis is among the earliest of Greek literature. It appears as a place in the works of Hesiod, a contemporary of Homer. Hesiod represents ethna by mythological ancestors. Ethnic history then becomes the personal narrative of the figures. Most of his works now only survive in fragments. In Fragment 5 of Catalogues he says:[23]

And she [Thyia, daughter of Deukalion] conceived and bare to Zeus, the hurler of the thunderbolt, two sons, even Magnes and Makedon, rejoicing in horses, who had their dwellings around Pieria and Olympos.

Homer does not mention Macedon, nor is there any word that might be interpreted as it in Linear B, but the Catalogue of Ships in the Iliad mentions that the Magnetes had moved away from Pieria (B756) before the Trojan War and were living in Magnesia. The Macedonians were left "around ... Olympus," the one starting point for the conquest of Emathia not mentioned by Thucydides. If the places of the Iliad are a reasonably accurate representation of Bronze Age Greece, as they are currently believed to be, then the Macedonians date to at least as early as the Late Bronze Age.[24]

Herodotus

Herodotus has something more to say about Macedonia of the late 6th and following 5th centuries BC, when it makes its first major debut in history, thanks to the Persian invasion. The story begins in Book V. Darius the Great had left an army in Thrace under his cousin Megabazus after his failed Scythian campaign of 513 BC with orders to reduce the region to satrapies. The Persian policy toward these satrapies was very liberal at the time. After a token submission, the rendering of earth and water, they were left to self-rule. The advantage to them was membership in the Persian economic sphere, but they had to cooperate with the demands of the Great King, beginning with the initial submission, about which the king would be very patient, but ultimately very insistent. He had compelled the Ionian Greeks to submit, but had left them alone until their revolt spurred him to action reluctantly. They had saved his army from total disaster against the Scythians and therefore had some credibility.

Xerxes I had resolved to invade Greece in 480 BC. He resolved to lead an army overland around the north of Greece, shadowed by and supported by a fleet keeping pace along the shore. The story is told in Book VII.

The entire north as far as, but not including, Thessaly was already "tributary to the king" (108). Thessaly was on the south side of the range. Xerxes crossed Thrace, marching inland of the coastal states that had been planted by peoples ejected by the Macedonians from Emathia, notably Piereis and Edoni. Evidently the Macedonian conquest had long been over. Most of Thrace therefore sided with the Persians.

Subsequently, the king crossed the Strymon, entering Macedonian country, which he celebrated by burning and burying alive a number of children of the village of Nine Ways in Macedonian Edonia (114). Herodotus tries to lessen the horror of this event by pointing out that the custom was intended as an offering to the gods. They were, so to speak, purchasing propitiousness for the expedition. Of course none of the Greeks viewed this as anything but a barbaric act, inflaming them against submission still further and creating solidarity where there had been none.

The Persians crossed Chalkidike. The ambivalent Greek communities there attempted to side with the king (115-117). They were forced to pay a heavy tribute in cash and goods by a suspicious king,(119) who did not offer any such terms to the Macedonians. Implicitly he was making a distinction between Thracians, Greeks, and Macedonians. He continued to offer the option of submission to the Greeks even though the southern Greeks not only refused but mistreated the envoys.

Seeing a major obstacle ahead, the Olympus-Pieria massifs, the king assembled his troops in Emathia with headquarters at Therma (early Thessalonika). His army was so large it required the whole coast from Therma around to the Haliakmon, about 112 km (70 mi). Supply was no problem, as they could continue to utilize the fleet. Herodotus says that all the rivers were used for water, and that one of them was drunk dry. In this part of the account the term Macedonia does not appear; instead, Herodotus uses the Emathian kingdom names, even though they were now populated by Macedonian speakers. For some reason he singles out the Axios as the border between Mygdonia and Bottiaea. Emathia is no longer mentioned.

Etymology

Folk-etymologies

Emathia was named after the Samothracian king Emathion and not after the local Emathus.

Greek terrain etymology

The etymology of the name is of Homeric Greek origin - ‘amathos’= sandy soil, opp. to sea-sand (psámathos = ψάμαθος); in plural the links or dunes by the sea, [compare êmathóeis = ἠμαθόεις/ἠμᾰθόεις (masc.), ēmathóessa = ἠμαθόεσσα (fem.), ēmathóen = ἠμαθόεν (neut.) epic for amathóeis/ámathos = ἀμᾰθόεις ἄμαθος[25] and êmathoessa (see above)[26] 'sandy', i. e. the coastal, sandy/swampy land around Axius river, in contrast to mountainous Macedonia, probably also intended as 'laying large land' (cf. PIE *mē-2, *m-e-t- 'to mow, to reap').[27]

Notes

- ^ "an overall average of rather less than a metre per millennium eustatic rise over the last 7000 years (C14). This agrees with a smoothed average from Butzer's worldwide plot (5b)."

- ^ This is a mere convention. Sea level is a global constant, except to geologists who are taking changes in the water content of the oceans into consideration. These types of water content change play a part in the storage of water in or release from global ice; otherwise, the masses changing gravitational potential in detail (by rising or falling) are rock.

- ^ Nea Nikomedeia village is not actually in urban Veria, nor is the site actually in urban Nea Nikomedeia, as enlargement of the maps will show.

- ^ The core is so named because Bottema selected it to be from the bed of filled Lake Giannitsa, or Lake Loudas, agricultural land when he took the core. It was published by him in 1976, so it is referenced in the literature as Giannitsa 1976, or Giannitsa Pollen Core, as Bottema was primarily interested in its pollen. The location is 40°40′00″N 22°19′00″E / 40.666667°N 22.316667°E. Actually, this location is more nearly 8 km from the archaeological site.

- ^ Bintliff uses " 11-12 m below sea level," meaning the top surface of the 12th m bsl.

- ^ "... in the post-orogenic subsidences the sub-furrows experienced most depression relative to their surrounding landscape."

- ^ In the coded terminology of carbon dating, bp is before present, BP is calibrated before present, bc is the calendar form of bp, BC is the calendar form of BP. In these archaeological sources, BC is almost never simple Before Christ and is therefore not replaceable by Before the Christian Era. Before present also is not that, but is before 1950, which for technical reasons replaces the calendar Anno Domini time. No matter what the current year, 1950 must be used in the conversion calculation from bp to BC. In that year, the amount of radioactive carbon in the atmosphere changed.

- ^ Dates taken at the NN site are not to be confused with dates taken at the core, even though they might all reference the same Neolithic events.

- ^ A core does not distinguish between subsidence rate and aggradation rate. Bintliff uses just sedimentation rate. In periods of high subsidence this will be the subsidence rate, and in periods of high aggradation, this will be the aggradation rate.

Citations

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 246, Figure 5a

- ^ Rodden 1965, p. 83

- ^ a b Bintliff 1976, p. 244, Figure 3

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 246

- ^ a b Bintliff 1976, p. 245

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 247

- ^ Bottema, Sytze (2010). "Bottema, Sytze (2010): Lithology of sediment core GIANNITB, Giannitsa, Greece". PANGAEA. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.741340. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 242

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 246, Figure 5b

- ^ a b Bintliff 1976, p. 241

- ^ Bottema, Sytze (2010). "Bottema, Sytze (2010): Age determination of sediment core GIANNITB, Giannitsa, Greece". PANGAEA. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.740373. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 243

- ^ Bintliff 1976, p. 255

- ^ Ghilardi 2015, Figure 1

- ^ Hammond 1972, p. 431

- ^ Morris 2014, pp. 1–2

- ^ Lilibaki-Akamati 2011, pp. 17–21

- ^ Prehistory of Macedonia, i. 418 n. 2

- ^ Iliad 14.226

- ^ The nine Muses and the nine Magpipes

- ^ Strab.Frag.7.11[which?]

- ^ Lucan (1. 1, 6. 360, 7. 166)

- ^ Mair, A.W. (1908). Hesiod: The Poems and Fragments Done into English Prose with Introduction and Appendices (PDF). Oxford: University of Oxford. p. 86.

- ^ Hammond 1972, p. 430

- ^ Liddell–Scott–Jones amathos

- ^ Pulon êmathoenta – Odyssey 1.93

- ^ Pokorny Pokorny's dictionary

Citation bibliography

- Bintliff, John (1976). "The Plain of Western Macedonia and the Neolithic Site of Nea Nikomedeia". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 42: 241–262. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00010768. hdl:1887/7952.

- Finkelberg, Margalit (2012). "Emathia". The Homer Encyclopedia. Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444350302.wbhe0413. ISBN 978-1-4051-7768-9.

- Ghilardi, Matthieu (2015). "Chapter 20. Geoarchaeological study of the Thessaloniki Plain (Greece): An adaptation of human societies to rapid Holocene shoreline displacements". La géoarchéologie française au xxie siècle [online]. Paris: CNRS Éditions. ISBN 9782271129932.

- Hammond, NGL (1997). "The location of Aegeae". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 117: 177–179. doi:10.2307/632555. ISSN 0075-4269. JSTOR 632555.

- Hammond, NGL (1972). Historical Geography and Prehistory. A History of Macedonia. Vol. I. London: Oxford University Press.

- Hatzopoulos, M.B. (2004). "Makedonia". In Hansen, M.H.; Nielsen, T.H. (eds.). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lilibaki-Akamati, Maria (2011). "Pella, Capital of the Macedonians: Historical and Archaeological Data". The Archaeological Museum of Pella (PDF). Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism. ISBN 9789609590006.

- Morris, Sarah (2014). Annual Report: Ancient Methone Archaeological Project 2014 Field School (PDF) (Report). Institute for Field Research.

- Rodden, Robert J. (1965). "An Early Neolithic Village in Greece". Scientific American. 212 (4): 82–93. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0465-82.

- Smith, William, ed. (1854). "Emathia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- Yiouni, Paraskevi (1992). The Pottery from Nea Nikomedeia in its Balkan Context (PhD thesis). University of London.

External links

![]() Media related to Emathia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Emathia at Wikimedia Commons