Elucidarium

Elucidarium (also Elucidarius, so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or summa about medieval Christian theology and folk belief, originally written in the late 11th century by Honorius Augustodunensis, influenced by Anselm of Canterbury and John Scotus Eriugena. It was probably complete by 1098, as the latest work by Anselm that finds mention is Cur deus homo. This suggests that it is the earliest work by Honorius, written when he was a young man. It was intended as a handbook for the lower and less educated clergy. Valerie Flint (1975) associates its compilation with the 11th-century Reform of English monasticism.

Overview

The work is set in the form of a Socratic dialogue between a disciple and his teacher, divided into three books. The first (De divinis rebus) discusses God, the creation of angels and their fall, the creation of man and his fall and need for redemption, and the earthly life of Christ. The second book (De regis ecclesiastics) discusses the divine nature of Christ and the foundation of the Church at Pentecost, understood as the mystical body of Christ manifested in the Eucharist dispensed by the Church. The third book (De futura vita) discusses Christian eschatology.[1] Honorius embraces this last topic with enthusiasm, with the Antichrist, the Second Coming, the Last Judgement, Purgatory, the pains of Hell, and the joys of Heaven described in vivid detail.

| Author | Honorius Augustodunensis |

|---|---|

| Subject | Christian theology |

| Genres | Summa |

Publication date | 1098-1101 |

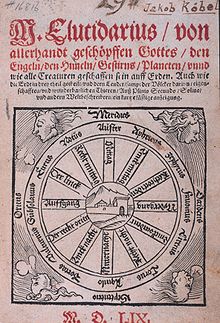

The work was very popular from the time of its composition and remained so until the end of the medieval period. The work survives in more than 300 manuscripts of the Latin text (Flint 1995, p. 162). The theological topic is embellished with many loans from the native folklore of England, and was embellished further in later editions and vernacular translations. Written in the 1090s in England, it was translated into late Old English within a few years of its completion (Southern 1991, p. 37). [dubious – discuss] It was frequently translated into vernaculars and survives in numerous disparate versions, from the 16th century also in print in the form of popular chapbooks. Later versions attributed the work to a "Master Elucidarius". A Provençal translation revises the text for compatibility with Catharism. An important early translation is that into Old Icelandic, dated to the late 12th century. The Old Icelandic translation survives in fragments in a manuscript dated to c. 1200 (AM 674 a 4to), one of the very earliest surviving Icelandic manuscripts. This Old Icelandic Elucidarius was an important influence on medieval Icelandic literature and culture, including the Snorra Edda.[2]

The editio princeps of the Latin text is that of the Patrologia Latina, vol. 172 (Paris 1895).

Summary

Book One - De divinis rebus

The first book begins with the narrator explaining the meaning of the titles as well as introducing himself as "The Master" who will be answering questions of "The Disciple". The purpose for this work is written to clear up doubts and questions that lay people and disciples alike have about Christianity. It begins with a discussion as to who is God, the Holy Trinity, and heaven. According to the Master God is a spiritual and consuming fire. The Holy Trinity is made up of God, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The Master explains that the Holy Trinity is made of three parts similar to how the sun is. These three parts are fire, light, and heat, which blend together similar to how the Trinity does. In his analogy, God is the fire, the Son is the light, and the Holy Ghost is the heat. This section continues on to a discussion about why God is called "Father" and why Jesus is called the "Son" rather than "Mother" and "Daughter". It concludes with the Master writing that God is called "Father" because He is the origin of everything and the Son is called so, not "Daughter", because a son is more like his father. Where does God live, the Disciple asks next. God lives in one of the three heavens, the Master states. The description of these three heavens can be compared to that found in 2 Corinthians 12. Humans can see the first of these heavens as it is physical. The second heaven houses the angels and is a spiritual heaven. Lastly, the third heaven is where the Holy Trinity reside.[3][4]

Next the Master explains God's omnipresence, all-knowing nature, and the creation of the world. This work follows the story written in Genesis 1 that the world was created in six days. Honorius writes what was created on which of these days; The first day is when God made light and the spiritual creatures; On the second day, heaven was made; The third day is when God made the earth and the sea; The fourth day God created the sun, moon, and stars, which all made the earthly temporal day; On the fifth day, God put birds in the sky and fish in the water; On the final and sixth day of the creation of the world God made humans and the other animals to reside on earth. After this explanation the Master tells the Disciple that all of these creations know God.[5]

With the mention of God's creations, the text moves on to discuss angels and humans. Of the angels, Satael (Satan), the Master states that did not even last an hour in heaven. Right after he was created he thought himself higher than God.[6] He alongside some of the angels who acknowledged his arrogance and followed him were thrown into hell. To this the disciple asks why God created angels with an ability to sin, which the Master answers by explaining that by giving them a freedom of choice the angels would have just merit before God. Additionally the Master explains that after the fall of the wicked angels those who were good became stronger and unable to sin. He begins an in-depth discussion about the nature of angels as well as devils.[7] Later in the narrative, the Master explains who Cherubim, the guardian of angels, is as in accordance with Genesis 3:24.[8]

Next the work focuses on humans. After the fall of the angels who followed Satael, the Master states that humans were made to make up the number of the elect that were lost. However, they only lasted seven hours in Paradise before the original sin was committed, which is discussed in the next section. He describes humans as being two parts, one spiritual and one physical. The former is the soul, which is made of a fire in God's likeness. The physical nature of humans is made of four elements that correlate to the world (blood is comparable to water, breath from the air, head is shaped like a globe just like the earth, etc.). Later in the text it is explained that humans were made by God in four ways; The first was without father and mother; The second was with only one man; The third was out of a man and woman; And the fourth was out of a Virgin alone.[9] The Master claims that humans were made out of such weak materials, as compared to the angels, to make the devil jealous. He says that the devil will be embarrassed to see these weak creatures be welcomed into heaven.[10]

The work continues with the discussion of creation. This time the focus is on the origin of things such as small earthly creatures, Adam, and Paradise. The Disciple asks why God made animals that are tiny and troublesome like mosquitoes. The Master states that God made these pests to humble humans by reminding them that they can be harmed by something so small.[11] Adam is then discussed. He is explained to have been created in Paradise. The work describes Paradise in accordance with Genesis 2:8 as being located in the East. The Master states that it is a place where aliments grow on trees to cure diseases as well as cure hunger, thirst, and exhaustion. After Adam was created, God made the first woman. Originally, the Master explains, men and women were to multiply without sinful lust while in Paradise as recorded in Genesis 3. Their children were to have no illnesses and to be able to communicate clearly and move around freely the moment they were born. This all was lost when Adam committed six sins, which are arrogance, disobedience, avarice, grave robbery, spiritual fornication, and manslaughter.[12] This begins an in-depth discussion of the fall of Adam.[13] Redemption is an important theme in the text of Elucidarius, so it is critical to identify that here the Master states that Adam could not be redeemed as he did nothing to atone for his sins. It is written in the text that the fall motivated God to send down His Son to redeem humankind.[13]

Next the Master addresses the immaculate conception and the nativity of Jesus. For the description of birth of Jesus Honorius relies on both the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. He writes of seven miracles that took place when Jesus was born; First a star was made, as mentioned in Matthew 2:2; Second the sun was circled by a golden ring; The third miracle was the emergence of an oil well; Fourth there was peace; The fifth miracle was when a census was taken which is correlated in Luke 2:1; The sixth was the death of thirty thousand enemies of God; Lastly, the seventh miracle was when animals spoke like humans. The Master discusses the meaning of each miracle after providing such a list. For example, he explains that the seventh miracle was when "the brutish flock of heathen people turned to the reason of God's Word'.[14] This continues into a description of the other events that happened after his brith, most notably the importance of baptism.[15]

The Master discusses Jesus' death and resurrection. The work states that since Jesus was without sin, He did not feel the pain of His death. He died because of His obedience to God, but this does not mean that God arranged for His son to die, but allowed Jesus to do what He chose to do for the sake of mankind. To the Master this is God showing His love for the people by sacrificing the best of all. This prompts the Disciple to ask that because the Father sacrificed His Son, what was wrong with when Judas sacrificed Christ. The Master answers by explaining that God sacrificed Jesus because of love, but Judas acted with his avarice, his greed. Through Jesus' death, all sins were forgiven, the Master states. Jesus was only dead for forty hours, which the Master explains is because the dead from quadrants of the world needed to be revived. He was in the tomb for two nights and a day, the Master states, because the nights symbolized two deaths, the death of the body and the death of the soul. After dying His soul goes to Paradise. The Master goes on to describe His resurrection, and all who He visited.[16]

In the last section of the first book, the Master answers the Disciple's questions regarding holy communion and corrupt religious teachers. He explains that in holy communion people consume bread to represent the body of Christ and wine to represent the blood of Christ because Jesus said He is the living life and the true grape as in John 6:51 and John 15:1, respectively. Additionally the Master notes that just as bread is made up of grains, Jesus is made up of saints. It is bread and wine because of all these things as well as because, the Master explains, nobody would dare consume the true flesh and blood of Christ. He continues to discuss the importance of taking holy communion, that it redeems people. However, those who act against God for the sake of money and power, such as corrupt teachers of God are the sellers of God as in Acts 8:20 and are defilers. The Master explains that these teachers such as the sons of Bishop Eli act in this way they become the blind leading the blind (1 Samuel 2:22-24) and even the innocent, if they follow, can be harmed. The text reads that people such as Judas partake in holy communion, but do not receive the flesh and blood of Jesus, they consumed poison instead. The Master states that the wicked cannot be taught the word of God and because of this one must endure others wickedness, but not partake in it. He concludes the first book of Elucidarium by declaring that God's children must endure evil as Jesus did and they must do so until He appears and divides the wicked from the worthy (Matthew 3:12; Luke 3:17).[17]

Editions and translations

Modern editions and translations

- Lefèvre, Yves, L'Elucidarium et les Lucidaires, Bibliothèque des écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome, 180 (Paris, 1954) (Latin with modern French translation)

- Ed. Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon, The Old Norse Elucidarius: original text and English translation, (Columbia, 1992) (Old Norse with English translation)

- Sorensen, Clifford Teunis Gerritt, The Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis: Translation and Selected Annotations, (Brigham Young University, 1979) (English translation)

Medieval translations

- High Middle Ages

- An Old Icelandic version of ca. 1200.[18]

- Ed. Evelyn Scherabon Firchow and Kaaren Grimstad, Elucidarius: in Old Norse translation, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi 36 (Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar, 1989).

- A thirteenth-century translation into Old French by the Dominican Jeffrey of Waterford

- A thirteenth-century translation into Middle High German, followed by a German-language ms. tradition of the 13th to 15th centuries [1]

- Late Middle Ages

- A Late Middle English translation of the fourteenth-century French, Second Lucidaire called The Lucidary

- A Provençal translation [2]

- A Middle Welsh version from the Llyvyr agkyr Llandewivrevi (Jesus college ms. 119, 1346)

- Ed. J. Morris Jones and John Rhŷs, The Elucidarium and other tracts in Welsh from Llyvyr agkyr Llandewivrevi A.D. 1346 (Jesus college ms. 119) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894)

- A fifteenth-century Czech translation [3]

- Sixteenth century

- Nuremberg, 1509.[4]

- Nuremberg, 1512.[5]

- Landshut, 1514.[6]

- Vienna, 1515.[7]

- Hermannus Torrentinus, Dictionarivm poeticvm qvod vvlgo inscribitur Elucidarius carminum, apvd Michaellem Hillenium, 1536 [8]; Elucidarius poeticus : fabulis et historiis refertissimus, iam denuo in lucem, cum libello d. Pyrckheimeri de propriis nominibus civitatum, arcium, montium, aeditus, Imprint Basileae : per Nicolaum Bryling., 1542 [9]

- Eyn newer M. Elucidarius, Strasbourg 1539 [10]

References

- ^ Flint, Valerie I.J. (January 1975). "The Elucidarius of Honorius Augustodunensis and Reform in Late Eleventh Century England". Revue Bénédictine. 85 (1–2): 178–189. doi:10.1484/j.rb.4.00818. ISSN 0035-0893.

- ^ Harðarson, Gunnar (January 2016). "The Argument from Design in the Prologue to theProse Edda". Viking and Medieval Scandinavia. 12: 79. doi:10.1484/j.vms.5.112418. ISSN 1782-7183.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ "Bibliotheca Polyglotta". www2.hf.uio.no. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 6–17. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ "Bibliotheca Polyglotta". www2.hf.uio.no. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 19–21, 25. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ a b Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 23–29. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 36–45. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Honorius; Firchow, Evelyn Scherabon; Honorius; Honorius (1992). The Old Norse Elucidarius. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (1st ed.). Columbia, SC: Camden House. pp. 44–53. ISBN 978-1-879751-18-7.

- ^ Magnús Eiríksson, "Brudstykker af den islandske Elucidarius," in: Annaler for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, Copenhagen 1857, pp. 238–308.

Cited sources

- Augustodunensis, Honorius. Elucidarium , University of Oslo Bibliotheca Polyglotta. Edited by J. Braarvid et al. Available at: https://www2.hf.uio.no/polyglotta/index.php?page=volume&vid=953.

- Valerie I. J. Flint, The Elucidarius of Honorius Augustodunensis and Reform in Late Eleventh-Century England, in: Revue bénédictine 85 (1975), 178–189.

- Marcia L. Colish, Peter Lombard, Volume 1, vol. 41 of Brill's studies in intellectual history (1994), ISBN 978-90-04-09861-9, 37–42.

- Th. Ricklin, "Elucidarium"; in: Eckert, Michael; Herms, Eilert; Hilberath, Bernd Jochen; Jüngel, Eberhard eds.): Lexikon der theologischen Werke, Stuttgart 2003, 263/264.

- Gerhard Müller, Theologische Realenzyklopädie, De Gruyter, 1993, ISBN 978-3-11-013898-6, p. 572.