Indian Canadians

Indo-Canadiens (French) | |

|---|---|

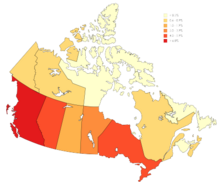

Indian ancestry in Canada (2016) | |

| Total population | |

| 1,858,755[1][a] 5.1% of the Canadian population (2021) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Toronto • Vancouver • Calgary • Edmonton • Montreal • Abbotsford • Winnipeg • Ottawa • Hamilton | |

| Languages | |

[2][3][4] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Sikhism (36%) Hinduism (32%) Minorities: Christianity (12%) Islam (11%) Irreligion (8%) Buddhism (0.1%) Judaism (0.1%) Indigenous (0.01%) Zoroastrianism · Jainism · Others (0.7%) [5][a] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian citizenship |

|---|

|

|

Indian Canadians are Canadians who have ancestry from India. The term East Indian is sometimes used to avoid confusion with Indigenous groups. Categorically, Indian Canadians comprise a subgroup of South Asian Canadians which is a further subgroup of Asian Canadians. As of the 2021 census, Indians are the largest non-European ethnic group in the country and form the fastest growing national origin in Canada.[6][7]

Canada contains the world's seventh-largest Indian diaspora. The highest concentrations of Indian Canadians are found in Ontario and British Columbia, followed by growing communities in Alberta and Quebec as well, with the majority of them being foreign-born.[7]

Terminology

In Canada, 'South Asian' refers to persons with ancestry throughout South Asia, while 'East Indian' means someone with origins specifically from India.[8] Both terms are used by Statistics Canada,[9]: 7 who do not use 'Indo-Canadian' as an official category for people.[9]: 8 Originating as a part of the Canadian government's multicultural policies and ideologies in the 1980s, 'Indo-Canadian' is a term used in mainstream circles of people in Canada as of 2004.[10]

In 1962, 'Pakistani' and 'Ceylonese' (Sri Lankan) were made into separate ethnic categories, while prior to that year people with those origins were counted as being 'East Indian'.[11] As of 2001 about half of foreign-born persons claiming an 'East Indian' ancestry originated from India, while others originated from Bangladesh, East Africa, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.[7][12]

Elizabeth Kamala Nayar, author of The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver: Three Generations Amid Tradition, Modernity, and Multiculturalism, defined 'Indo-Canadians' as persons born in Canada of Indian subcontinent origins.[10] Kavita A. Sharma, author of The Ongoing Journey: Indian Migration to Canada, wrote that she used 'Indo-Canadians' to only refer to those of origins from India who have Canadian citizenship. Otherwise she uses "Indo-Canadian" in an interchangeable manner with 'South Asians' and 'East Indians'.[13] Priya S. Mani, the author of "Methodological Dilemmas Experienced in Researching Indo-Canadian Young Adults’ Decision-Making Process to Study the Sciences," defined "Indo-Canadian" as being children of persons who immigrated from South Asia to Canada.[14] Exploring brown identity, Widyarini Sumartojo, in a PhD thesis, wrote that, while "'South Asian'...refers to a broader group of people, it is often used somewhat interchangeably with 'East Indian' and 'Indo-Canadian.'"[9]: 7

Despite the diversity in ethnic groups and places of origin among South Asians, previously the term 'South Asian' had been used to be synonymous with 'Indian'.[15] The Canadian Encyclopedia stated that the same population has been "referred to as South Asians, Indo-Canadians or East Indians," and that people referred to as 'South Asian' view the term in the way that those from European countries might view the label 'European.'"[16] According to Nayar, "Many Canadian-born South Asians dislike the term because it differentiates them from other Canadians."[10] Martha L. Henderson, author of Geographical Identities of Ethnic America: Race, Space, and Place, argued that the 'South Asian' term "is meaningful as a defining boundary only in interactions between South Asians and mainstream Canadians."[15] Henderson added that, because of the conflation of 'South Asian' and 'Indian', "[i]t is very difficult to isolate the history of Asian Indians in Canada from that of other South Asians."[15]

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 11 | — |

| 1901 | 100 | +809.1% |

| 1911 | 2,342 | +2242.0% |

| 1921 | 1,016 | −56.6% |

| 1931 | 1,400 | +37.8% |

| 1941 | 1,465 | +4.6% |

| 1951 | 2,148 | +46.6% |

| 1961 | 6,774 | +215.4% |

| 1971 | 67,925 | +902.7% |

| 1981 | 165,410 | +143.5% |

| 1986 | 261,435 | +58.1% |

| 1991 | 423,795[b] | +62.1% |

| 1996 | 638,345[c] | +50.6% |

| 2001 | 813,730[d] | +27.5% |

| 2006 | 1,072,380[e] | +31.8% |

| 2011 | 1,321,360[f] | +23.2% |

| 2016 | 1,582,215[g] | +19.7% |

| 2021 | 1,858,755[a] | +17.5% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [17]: 332 [18][19]: 15 [20]: 16 [21]: 354&356 [22]: 503 [23]: 272 [24]: 2 [25]: 484 [26]: 5 [27]: 2 [28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][1] Note1: 1951-1971 census counts include all individuals with South Asian origins. Note2: 1981 Canadian census did not include multiple ethnic origin responses, thus population is an undercount. | ||

Late 19th century

The Indo-Canadian community began to form around the late 19th century, pioneered by men, the great majority of whom were Punjabi Sikhs—primarily from farming backgrounds—with some Punjabi Hindus and Punjabi Muslims, and many of whom were veterans of the British Indian Army.[37] Canada was part of the British Empire, and since India was also under British rule, Indians were also British subjects. In 1858, Queen Victoria had proclaimed that, throughout the Empire, the people of India would enjoy "equal privileges with white people without discrimination of colour, creed or race."[38]

The first census which took place following Canadian Confederation was in 1871 and enumerated the four original provinces including, Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick found that the population with racial origins from India (then-labeled as "Hindu" on the census) stood at 11 persons or 0.0003 percent of the national population, with 8 persons from Ontario, and the remaining 3 persons from Nova Scotia.[17]: 332

In 1897, contingents of Sikh soldiers apart of the Sikh Regiment and Punjab Regiment participated in the parade to celebrate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee in London, England. On their subsequent journey home, they visited the western coast of Canada, primarily British Columbia, which—because of its very sparse population at the time—the Canadian government wanted to settle in order to prevent a takeover of the territory by the United States.

Upon retiring from the army, some soldiers found their pensions to be inadequate, and some also found their land and estates back in India were being utilized by money lenders. Deciding to try their fortunes in the countries they had visited, these men joined an Indian diaspora, which included people from Burma through Malaysia, the East Indies, the Philippines, and China. The vanguard was able to find work within the police force and some were employed as night-watchmen by local firms. Others started small businesses of their own. Such work would provide wages that were very high by Indian standards.[39]

They were guaranteed jobs by agents of large Canadian companies such as the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Hudson's Bay Company. Having seen Canada for themselves, Punjabis sent home letters to their fellow countrymen, recommending them to come to the 'New World'.[39] Though initially reluctant to go to these countries due to the treatment of Asians by the white population, many young men chose to go upon the assurance that they would not meet the same fate.[38]

Government quotas were also established to cap the number of Indians allowed to immigrate to Canada in the early 20th century. This was part of a policy adopted by Canada to ensure that the country retained its primarily European demographic, and was similar to American and Australian immigration policies at the time. These quotas only allowed fewer than 100 people from India a year until 1957, when it was marginally increased (to 300 people a year). In comparison to the quotas established for Indians, Christians from Europe immigrated freely without quotas in large numbers during that time to Canada, numbering in the tens of thousands yearly.[40]

Early 20th century

Throughout history up to the present day, the majority of South Asian Canadians have been of Indian origin. Following their brief passage through British Columbia in 1897, Canada had an estimated 100 persons of Punjabi Sikh origin by 1900, concentrated in the western province.[41] Canada's first relatively major wave of South Asian immigration—all men arrived in Vancouver in 1903.[37] These migrants had heard of Canada from Indian troops in Hong Kong, who had travelled through Canada the year prior on their way to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII.[37]

Upon arrival to BC, the immigrants faced widespread racism by white Canadians, most of whom feared that migrant workers would work for less pay and that an influx of immigrants would threaten their jobs. (The same threat was perceived for the Japanese and Chinese immigrants before them.) As a result, a series of race riots targeted the Indian immigrants—as well as other Asian groups, such as the Chinese railroad workers, and Black Canadians—who were beaten up by mobs of angry white Canadians, though often met with retaliation.[40]

A notable moment in early Indo-Canadian history was in 1902 when Punjabi Sikh settlers first arrived in Golden, British Columbia to work at the Columbia River Lumber Company.[42] These early settlers built the first Gurdwara (Sikh temple) in Canada and North America in 1905,[43][44] which would later be destroyed by fire in 1926.[45] The second Gurdwara to be built in Canada was in 1908 in Kitsilano (Vancouver), aimed at serving a growing number of Punjabi Sikh settlers who worked at nearby sawmills along False Creek at the time.[46] The Gurdwara would later close and be demolished in 1970, with the temple society relocating to the newly built Gurdwara on Ross Street, in South Vancouver.

As a result, the oldest existing Gurdwara in Canada today is the Gur Sikh Temple, located in Abbotsford, British Columbia. Built in 1911, the temple was designated as a national historic site of Canada in 2002 and is the third-oldest Gurdwara in the country. Later, the fourth Gurdwara to be built Canada was established in 1912 in Victoria on Topaz Avenue, while the fifth soon was built at the Fraser Mills (Coquitlam) settlement in 1913, followed a few years later by the sixth at the Queensborough (New Westminster) settlement in 1919,[47][48][49] and the seventh at the Paldi (Vancouver Island) settlement, also in 1919.[50][51][52][53]

Attracted by high Canadian wages, early migrants temporarily left their families in search of employment in Canada. In 1906 and 1907, a spike in migration from the Indian subcontinent took place in British Columbia, where an estimated 4,747 arrived, at around the same time as a rise in Chinese and Japanese immigration.[40][18][19] This rapid increase in immigration totaled 5,179 by the end of 1908.[37][18][19] With the federal government curtailing the migration, fewer than 125 South Asians were permitted to land in BC over the next several years. Those who had arrived were often single men and many returned to British India or British Hong Kong, while others sought opportunities south of the border in the United States, as the 1911 Canadian Census later revealed the South Asian Canadian population had declined to 2,342 persons or 0.03 percent of the national population.[54][19][55]

In support of the vast white population who did not want Indians to immigrate to Canada, the BC government quickly limited the rights and privileges of South Asians.[37] In 1907, provincial disenfranchisement hit the South Asians, who were thus denied the federal vote and access to political office, jury duty, professions, public-service jobs, and labour on public works.[37][40] The next year, the federal government put into force an immigration regulation that specified that migrants must travel to Canada through continuous journey from their country of origin. As there were no such system between India and Canada—which the Canadian government knew—the continuous-journey provision therefore prevented the endurance of South Asian immigration. Separating Indian men from their families, this ban would further stifle the growth of the Indo-Canadian community.[37][40][39] Another federal law required new Indian immigrants to carry $200 in cash upon arrival in Canada, whereas European immigrants required only $25 (this fee did not apply to Chinese and Japanese, who were kept out by other measures).[39][56]

In November 1913, a Canadian judge overruled an immigration department order for the deportation of 38 Punjabis, who had come to Canada via Japan on a regularly scheduled Japanese passenger liner, the Panama Maru. They were ordered deported because they had not come by continuous journey from India nor did they carry the requisite amount of money. The judge found fault with the two regulations, ruling both of their wording to be inconsistent with that of the Immigration Act and therefore invalid.[39] With the victory of the Panama Maru, whose passengers were allowed to land, the sailing of the SS Komagata Maru—a freighter carrying 376 South Asian passengers (all British subjects)—took place the following year in April.[39] On 23 May 1914, upon the eve of the First World War, the Komagata Maru candidly challenged the 'continuous journey' regulation when it arrived in Vancouver from Punjab.[39][54] However, although invalidated for a couple months, the 'continuous journey' and $200 requirement provisions returned to force by January 1914, after the Canadian government quickly rewrote its regulations to meet the objections it encountered in court.[39] The ship had not sailed directly from India; rather, it came to Canada via Hong Kong, where it had picked up passengers of Indian descent from Moji, Shanghai, and Yokohama. As expected, most of the passengers were not allowed to enter Canada. Immigration officials consequently isolated the ship in Vancouver Harbour for 2 months and was forced to return to Asia.[37] Viewing this as evidence that Indians were not treated as equals in the Empire, they staged a peaceful protest upon returning to India in Calcutta. The colonial authorities in Calcutta responded by dispatching a mixed force of policemen and soldiers, and a subsequent violent encounter between the two parties resulted in the deaths of several protestors.[39] These events would give further evidence to South Asians of their second-class status within the Empire.[39]

By 1914, it is estimated that the number of South Asians in British Columbia fell to less than 2,000.[54] Canada would eventually allow the wives and dependent children of South Asian Canadian residents to immigrate in 1919. Though a small flow of wives and children would be established by the mid-1920s, this did not offset the effect of migration by South Asian Canadians to India and the U.S., which saw the reduction of the South Asian population in Canada to about 1,300 by the mid-1920s.[37]

One of the earliest immigrants from India to settle in Alberta was Sohan Singh Bhullar.[57] Like other Indo-Canadians in Alberta at the time, Bhullar attended the local Black church. The two communities formed close ties due to the marginalization of both communities by wider society. Bhullar's daughter is famed Jazz musician Judi Singh.[57]

Mid–20th century

With the independence of India being an emanant concern, the federal continuous-journey regulation was removed in 1947.[37] Most of British Columbia's anti-South Asian legislation would also be withdrawn in 1947, and the Indo-Canadian community would be returned the right to vote.[37][40] At that time, thousands of people were moved across the nascent borders of the newly-established India and Pakistan. Research in Canada suggests that many of the early Goans to emigrate to Canada were those who were born and lived in Karachi, Mumbai (formerly Bombay), and Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). Another group of people that arrived in Canada during this period were the Anglo-Indians, people of mixed European and Indian ancestry.[40]

In 1951, in place of the continuous-journey provision, the Canadian government would enact an annual immigration quota for India (150 per year), Pakistan (100), and Ceylon (50).[37] At that time, there were only 2,148 South Asians in Canada.

A significant event in Indo-Canadian history occurred in 1950 when 25 years after settling in Canada and nine years after moving to British Columbia from Toronto, Naranjan "Giani" Singh Grewall became the first individual of Indian ancestry in Canada and North America to be elected to public office after successfully running for a position on the board of commissioners in Mission, BC against six other candidates.[58][59][60][61][62] Grewall was re-elected to the board of commissioners in 1952 and by 1954, was elected to became mayor of Mission.[58][61][62]

"Thank you all citizens of Mission City [...] It is a credit to this community to elect the first East Indian to public office in the history of our great dominion. It shows your broad-mindedness, tolerance and consideration.".[60]

— Notice by Naranjan Singh Grewall in the local Mission newspaper following his election to public office, 1950

A millwright and union official, and known as a sportsman and humanitarian philanthropist as well as a lumberman, Grewall eventually established himself as one of the largest employers and most influential business leaders in the northern Fraser Valley, owned six sawmills and was active in community affairs serving on the boards or as chairman of a variety of organizations, and was instrumental in helping create Mission's municipal tree farm.[58][60][61][62][63] With strong pro-labour beliefs despite his role as a mill-owner, after a scandal embroiled the provincial Ministry of Forestry under the-then Social Credit party government, he referred to holders of forest management licenses across British Columbia as Timber Maharajahs, and cautioned that within a decade, three or four giant corporations would predominantly control the entire industry in the province, echoing similarities to the archaic zamindar system in South Asia.[61][63] He later ran unsuccessfully for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the precursor of today's New Democratic Party) in the Dewdney riding in the provincial election of 1956.[62][63]

While by the 1950s, Indo-Canadians had gained respect in business in British Columbia primarily for their work in owning sawmills and aiding the development of the provincial forestry industry, racism still existed especially in the upper echelons of society.[61][64] As such, during the campaign period and in the aftermath of running for MLA in 1956, Grewall received personal threats, while the six mills he owned along with his house were all set ablaze by arsonists.[64][h] One year later, on July 17, 1957, while on a business trip, he was suspiciously found dead in a Seattle motel, having been shot in the head.[h][i][64][65] Grewall Street in Mission was named in his honour.[66]

“Every kid in the North Fraser, who thinks he or she is being discriminated against, should read the Grewall story and the challenges he faced.”.[h]

— Former B.C. premier Dave Barrett on Naranjan Singh Grewall

Moderate expansion of immigration increased the Canadian total to 6,774 by 1961, then grew it to 67,925 by 1971. By 2011 the South Asian population in Canada was 1,567,400.[37]

Policies changed rapidly during the second half of the 20th century. Until the late 1950s, essentially all South Asians lived in British Columbia. However, when professional immigrants came to Canada in larger numbers, they began to settle across the country. South Asian politics until 1967 were primarily concerned with changing immigration laws, including the elimination of the legal restrictions enacted by the BC Legislature.[37]

In 1967, all immigration quotas in Canada based on specific ethnic groups were scrapped.[40] The social view in Canada towards people of other ethnic backgrounds was more open, and Canada was facing declining immigration from European countries, since these European countries had booming postwar economies, and thus more people decided to remain in their home countries.

In 1972, all South Asians were expelled from Uganda,[37][67] including 80,000 individuals of Indian (mostly Gujarati) descent.[68][69] Canada accepted 7,000 of them (many of whom were Ismailis) as political refugees.[37] From 1977–85, a weaker Canadian economy significantly reduced South-Asian immigration to about 15,000 a year.[37] In 1978, Canada introduced the Immigration Act, 1976, which included a point-based system, whereby each applicant would be assessed on their trade skills and the need for these skills in Canada.[70] This allowed many more Indians to immigrate in large numbers and a trickle of Goans (who were English-speaking and Catholic) began to arrive after the African Great Lakes countries imposed Africanization policies.[71]

The 1970s also saw the beginning of the migration from Fiji, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Mauritius.[37] During this decade, thousands of immigrants came yearly and mainly settled in Vancouver and Toronto.

Late 20th century

In 1986, following the British Columbia provincial election, Moe Sihota became the first Indo-Canadian to be elected to provincial parliament. Sihota, who was born in Duncan, British Columbia in 1955, ran as the NDP Candidate in the riding of Esquimalt-Port Renfrew two years after being involved in municipal politics, as he was elected as an Alderman for the city of Esquimalt in 1984.

Significant urbanization of the Indo-Canadian community began during the 1980s and early 1990s, when tens of thousands of immigrants moved from India into Canada each year. Forming nearly 20% of the population, Fort St. James had the highest proportion of Indo-Canadians of any municipality in Canada during the 1990s.[72] Prior to the large urban concentrations that exist in the present day, statistically significant populations existed across rural British Columbia; a legacy of previous waves of immigration earlier in the 20th century.[72] In 1994, approximately 80% of South-Asian Canadians were immigrants.[37] The settlement pattern in the most recent two decades is still mainly focused around Vancouver and Toronto, but other cities such as Calgary, Edmonton, and Montreal have also become desirable due to growing economic prospects in these cities.

21st century

During the late 20th and into the early 21st century, India was the third highest source country of immigration to Canada, with roughly 25,000–30,000 Indians immigrating to Canada each year according to Statistics Canada data. India became the highest source country of immigration to Canada by 2017, with yearly permanent residents increasing from 30,915 in 2012 to 85,585 in 2019, representing 25% of total immigration to Canada. Additionally, India also became the top source country for international students in Canada, rising from 48,765 in 2015 to 219,855 in 2019.[73] Mirroring historical Indo-Canadian migration patterns, the majority of new immigrants from India continue to hail from Punjab,[74] with an increasing proportion also hailing from Haryana, Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh.

Demography

Population

| Year | Population | % of total population |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 [41] |

>100 | 0.002% |

| 1911 [21]: 354&356 |

2,342 | 0.032% |

| 1921 [21]: 354&356 |

1,016 | 0.012% |

| 1931 [22]: 503 |

1,400 | 0.013% |

| 1941 [23]: 272 [24]: 2 |

1,465 | 0.013% |

| 1951 [25]: 484 |

2,148 | 0.015% |

| 1961 [26]: 5 |

6,774 | 0.037% |

| 1971 [27]: 2 |

67,925 | 0.315% |

| 1981 [28] |

165,410 | 0.687% |

| 1986 [29][30] |

261,435 | 1.045% |

| 1991 [31][b] |

423,795 | 1.57% |

| 1996 [32][c] |

638,345 | 2.238% |

| 2001 [33][d] |

813,730 | 2.745% |

| 2006 [34][e] |

1,072,380 | 3.433% |

| 2011 [35][f] |

1,321,360 | 4.022% |

| 2016 [36][g] |

1,582,215 | 4.591% |

| 2021 [1][a] |

1,858,755 | 5.117% |

As of 2021, the Indo-Canadian population numbers approximately 1.86 million.[1][a]

Religion

Until the 1950s, Sikhs formed up to 95% of the entire Indo-Canadian population.[75]: 4

In the contemporary era, Canadians with Indian ancestry are from very diverse religious backgrounds compared to many other ethnic groups, which is due in part to India's multi-religious population.[76] Amongst the Indo-Canadian population however, the religious views are more evenly divided than India, owing in part to historical chain migration patterns, witnessed predominantly in the Sikh-Canadian community.

A census report detailing the religious proportion breakdown of the South Asian Canadian community was done between 2005 and 2007 by Statistics Canada, with results derived from the 2001 Canadian census.[7][77] This report found that among the Indo-Canadian population, Sikhs represented 34%, Hindus 27%, Muslims 17%, and Christians 16% (7% Protestant/Evangelical + 9% Catholic).[7][k] Relatively few people of Indian origin have no religious affiliation. In 2001, just 4% said they had no religious affiliation, compared with 17% of the Canadian population.[k]

| Religious group | 2021[5] | |

|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | |

| Sikhism | 674,860 | 36.31% |

| Hinduism | 588,345 | 31.65% |

| Christianity | 229,290 | 12.34% |

| Islam | 205,985 | 11.08% |

| Irreligion | 143,355 | 7.71% |

| Buddhism | 2,535 | 0.14% |

| Judaism | 1,515 | 0.08% |

| Indigenous | 115 | 0.01% |

| Other | 12,740 | 0.69% |

| Total Indo-Canadian population | 1,858,755 | 100% |

Sikhism

There are over 175 gurdwaras in Canada, the oldest of which was built in 1905 in Golden, BC, serving settlers who worked for the Columbia River Lumber Company,[43][44] which would later be destroyed by fire in 1926.[45] The second-oldest gurdwara was built in 1908 in the Kitsilano neighbourhood of Vancouver and similarly served early settlers who worked at nearby sawmills along False Creek at the time.[46] The temple eventually closed in 1970 as the Sikh population relocated to the Sunset neighbourhood of South Vancouver.

The oldest gurdwara still in service is the Gurudwara Gur Sikh Temple, located in Abbotsford, BC. Built in 1911, the gurdwara was designated as a National Historic Site in 2002.[78]

The Ontario Khalsa Darbar, in Mississauga, is the largest Gurudwara in Canada. The other notable Gurudwaras include Gurudwara Guru Nanak Darbar Montreal, Gurudwara Dashmesh Darbar Brampton and the Sikh Society of Manitoba.

The largest Sikh populations in Canada are located in British Columbia and Ontario, concentrated in Greater Vancouver (Surrey) and Greater Toronto (Brampton).

- Gur Sikh Temple (Abbotsford)

- Gurudwara Nanaksar Sahib, Edmonton, Alberta

- Vancouver Sikh Temple, c. 1911

Hinduism

According to the 2021 census, there are 828,195 Hindus in Canada, up from 297,200 in the 2001 census.[79][80] and over 180 Hindu temples across Canada with almost 100 in the Greater Toronto Area alone.[81] Early in history when Hindus first arrived, the temples were more liberal and catered to all Hindus from different communities. In the past few decades, with the number of Hindu Canadians increasing, Hindu temples have now been established to cater to specific communities of different languages. There are temples for Punjabis, Haryanvis, Gujaratis, Tamils, Bengalis, Sindhis, Trinidadians, Guyanese, etc.

Within Toronto, the largest Hindu temple in Canada is located on Claireville Drive, which is called the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Toronto. The entire Mandir is 32,000 sq ft (3,000 m2) and hosts numerous events on the Hindu religious calendar.

The Hindu Heritage Centre is another very large temple and perhaps the second biggest temple at 25,000 sq ft (2,300 m2) serving the Hindu community of Brampton and Mississauga. The temple is a very liberal Sanatani Dharmic Hindu temple which caters to the need of all different types of Hindus. Its devotees come from North and South India, as well as Pakistan, Nepal, and the West Indies. The centre is also focused on preserving Hindu culture by teaching a variety of different classes.

- The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Toronto in Etobicoke, Ontario, built by Canada's Gujarati Hindu community.

- Hindu Heritage Centre in Mississauga, Ontario.

Islam

There are also many Islamic societies and mosques throughout Canada, which have been established and supported by non-Indian and Indian Muslims alike.

Many Indian Muslims along with Muslims of other nationalities worship at one of the largest mosques in Canada, the ISNA Centre, located in Mississauga. The facility contains a mosque, high school, community centre, banquet hall and funeral service available for all Muslim Canadians.

The Ismailis have the first Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre set up in Burnaby, British Columbia. This high-profile building is the second in the world, with other locations in London, Lisbon, and Dubai. A second such building is in Toronto.

Christianity

Indian Christians tend to attend churches based on their state of origin and their particular traditions including the Roman Catholic Church, Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Assemblies of God in India, Church of God (Full Gospel) in India, The Pentecostal Mission, Church of North India, Church of South India, Mar Thoma Syrian Church, Malankara Orthodox Church, and Indian Pentecostal Church.

The majority of people of Goan origin in Canada are Roman Catholics who share the same parish churches as other Catholic Canadians, however, they often celebrate the feast of St Francis Xavier, who is the Patron Saint of the Indies, and whose body lies in Goa. Syro-Malabar Catholics have established a diocese for themselves, called the Syro-Malabar Catholic Eparchy of Mississauga which serves all the Syro-Malabar faithful across Canada.[82]

Language

Indo-Canadians speak a variety of languages, reflecting the cultural and ethnic diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

The most widely spoken South Asian language in Canada is Punjabi, which is spoken by the people from Punjab state and Chandigarh in India and by the people from Punjab province and Islamabad Capital Territory in Pakistan. In Canada, Punjabi is a language mainly spoken by South Asian Canadians with ties to the state of Punjab in Northern India.

Hindi, as India's most spoken language, is now the language primarily used by new Indian immigrants, especially ones with ties to Northern India and Central India.

Another widely spoken language by South Asians is Tamil. These individuals hail from the state of Tamil Nadu in Southern India or Northern Sri Lanka.

Gujarati is spoken by people from the Indian state of Gujarat. Gujarati Hindus and Ismaili Muslims from the African Great Lakes who subsequently migrated to Canada speak Gujarati. Zoroastrians from the western part of India form a small percentage of the population in Canada and also speak Gujarati.

Urdu is primarily spoken by Muslim South Asians from Northern India and Pakistan. However, individuals of Indian descent from Africa and the Caribbean may also speak it.

Kannada is spoken by people from the Indian state of Karnataka in Southern India

Bengali is spoken by individuals from the Indian state of West Bengal in Eastern India, as well as by the people of Bangladesh.

There are also a large number of Malayalam language speakers who hail from the state of Kerala in Southern India.

There is also a community of Goans from the African Great Lakes. However, only a few members of this community speak their original language Konkani.

Marathi is spoken by 12,578 people in Canada who have their roots in the Indian state of Maharashtra.

Telugu is spoken by 15,655 people in Canada who primarily hail from the Indian states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

Meitei (Manipuri[83]) is also spoken by some Indo-Canadians.[84]

Knowledge of language

Many Indo-Canadians speak Canadian English or Canadian French as a first language, as many multi-generational individuals do not speak Indian languages as a mother tongue, but instead may speak one or multiple[l] as a second or third language.

| Language | 2021[2][3] | 2016[85] | 2011[86][87] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hindustani* [m] |

1,176,295 | 3.24% | 755,585 | 2.19% | 576,165 | 1.74% |

| Punjabi* | 942,170 | 2.59% | 668,240 | 1.94% | 545,730 | 1.65% |

| Tamil* | 237,890 | 0.65% | 189,860 | 0.55% | 179,465 | 0.54% |

| Gujarati | 209,410 | 0.58% | 149,045 | 0.43% | 118,950 | 0.36% |

| Bengali* | 120,605 | 0.33% | 91,220 | 0.26% | 69,490 | 0.21% |

| Malayalam | 77,910 | 0.21% | 37,810 | 0.11% | 22,125 | 0.07% |

| Telugu | 54,685 | 0.15% | 23,160 | 0.07% | 12,645 | 0.04% |

| Marathi | 35,230 | 0.1% | 15,570 | 0.05% | 9,695 | 0.03% |

| Kannada | 18,420 | 0.05% | 8,245 | 0.02% | 5,210 | 0.02% |

| Kacchi | 15,085 | 0.04% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Konkani | 8,950 | 0.02% | 6,790 | 0.02% | 5,785 | 0.02% |

| Sindhi* | 8,385 | 0.02% | 20,260 | 0.06% | 15,525 | 0.05% |

| Oriya | 3,235 | 0.01% | 1,535 | 0.004% | N/A | N/A |

| Kashmiri* | 1,830 | 0.01% | 905 | 0.003% | N/A | N/A |

| Tulu | 1,765 | 0.005% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Assamese | 1,155 | 0.003% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

* These languages are also spoken by Canadians with ancestry from other nations of South Asia/Indian Subcontinent, including: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka | ||||||

Mother tongue

| Language | 2021[3][4] | 2016[85][88] | 2011[87][89] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Punjabi* | 763,785 | 2.09% | 543,495 | 1.56% | 459,990 | 1.39% |

| Hindustani* [m] |

521,990 | 1.43% | 377,025 | 1.08% | 300,400 | 0.91% |

| Tamil* | 184,750 | 0.5% | 157,125 | 0.45% | 143,395 | 0.43% |

| Gujarati | 168,800 | 0.46% | 122,455 | 0.35% | 101,310 | 0.31% |

| Bengali* | 104,325 | 0.28% | 80,930 | 0.23% | 64,460 | 0.19% |

| Malayalam | 66,230 | 0.18% | 32,285 | 0.09% | 17,695 | 0.05% |

| Telugu | 39,685 | 0.11% | 18,750 | 0.05% | 10,670 | 0.03% |

| Marathi | 19,570 | 0.05% | 9,755 | 0.03% | 6,655 | 0.02% |

| Kacchi | 9,855 | 0.03% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kannada | 9,140 | 0.02% | 4,795 | 0.01% | 3,140 | 0.01% |

| Sindhi* | 5,315 | 0.01% | 13,880 | 0.04% | 12,935 | 0.04% |

| Konkani | 5,225 | 0.01% | 4,255 | 0.01% | 3,535 | 0.01% |

| Oriya | 2,305 | 0.01% | 1,210 | 0.003% | N/A | N/A |

| Kashmiri* | 1,015 | 0.003% | 620 | 0.002% | N/A | N/A |

| Tulu | 910 | 0.002% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Assamese | 715 | 0.002% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Parsi | 635 | 0.002% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Marwari | 395 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Saurashtra | 345 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pahari | 255 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kurux | 245 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Memoni | 240 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Haryanvi | 230 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Maithili | 230 | 0.001% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chakma* | 180 | 0.0005% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bhojpuri | 145 | 0.0004% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dogri | 120 | 0.0003% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Garhwali | 115 | 0.0003% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Rajasthani | 105 | 0.0003% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kodava | 100 | 0.0003% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bishnupuriya | 90 | 0.0002% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Oadki | 60 | 0.0002% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

* These languages are also spoken by Canadians with ancestry from other nations of South Asia/Indian Subcontinent, including: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka | ||||||

Spoken at home

| Language | Total | Only speaks | Mostly speaks | Equally speaks | Regularly speaks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punjabi* | 280,540 | 132,380 | 71,660 | 29,220 | 47,280 |

| Hindi | 165,890 | 114,175 | 116,075 | 19,090 | 26,550 |

| Urdu* | 89,365 | 30,760 | 27,840 | 12,200 | 18,565 |

| Tamil* | 97,345 | 45,865 | 29,745 | 9,455 | 12,280 |

| Gujarati | 60,105 | 18,310 | 16,830 | 7,175 | 17,790 |

| Malayalam | 6,570 | 1,155 | 1,810 | 505 | 3,100 |

| Bengali* | 29,705 | 12,840 | 9,615 | 2,780 | 4,470 |

* These languages are also spoken in Canada by immigrants from other South Asian countries such as: Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka | |||||

Geographical distribution

Provinces & territories

Canadian provinces and territories by their ethnic Indo-Canadian population as per the 2001 Canadian census, 2006 Canadian census, 2011 Canadian census, and 2016 Canadian census below.

| Province/territory | 2016[36] | 2011[35] | 2006[34] | 2001[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Ontario | 774,495 | 5.85% | 678,465 | 5.36% | 573,250 | 4.77% | 413,415 | 3.66% |

| British Columbia |

309,315 | 6.78% | 274,060 | 6.34% | 232,370 | 5.7% | 183,650 | 4.75% |

| Alberta | 174,510 | 4.39% | 125,105 | 3.51% | 88,165 | 2.71% | 61,180 | 2.08% |

| Quebec | 51,650 | 0.65% | 48,535 | 0.63% | 41,595 | 0.56% | 34,125 | 0.48% |

| Manitoba | 34,470 | 2.78% | 21,705 | 1.85% | 14,860 | 1.31% | 12,135 | 1.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 18,695 | 1.75% | 7,825 | 0.78% | 4,465 | 0.47% | 3,245 | 0.34% |

| Nova Scotia |

6,255 | 0.69% | 4,635 | 0.51% | 3,890 | 0.43% | 2,860 | 0.32% |

| New Brunswick |

2,150 | 0.29% | 2,605 | 0.35% | 2,215 | 0.31% | 1,320 | 0.18% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

1,820 | 0.36% | 1,400 | 0.28% | 1,275 | 0.25% | 940 | 0.19% |

| Prince Edward Island |

615 | 0.44% | 250 | 0.18% | 255 | 0.19% | 100 | 0.07% |

| Northwest Territories |

355 | 0.86% | 165 | 0.4% | 130 | 0.32% | 165 | 0.44% |

| Yukon | 320 | 0.91% | 310 | 0.93% | 145 | 0.48% | 185 | 0.65% |

| Nunavut | 65 | 0.18% | 80 | 0.25% | 40 | 0.14% | 25 | 0.09% |

| Canada | 1,582,215[g] | 4.59% | 1,321,360[f] | 4.02% | 1,072,380[e] | 3.43% | 813,730[d] | 2.75% |

| Province/ Territory |

1961[26]: 5 | 1951[25]: 484 | 1941[23]: 272 [24]: 2 | 1931[22]: 503 | 1921[21]: 354&356 | 1911[21]: 354&356 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| British Columbia |

4,526 | 0.28% | 1,937 | 0.17% | 1,343 | 0.16% | 1,283 | 0.18% | 951 | 0.18% | 2,292 | 0.58% |

| Ontario | 1,155 | 0.02% | 76 | 0% | 21 | 0% | 43 | 0% | 28 | 0% | 17 | 0% |

| Quebec | 483 | 0.01% | 61 | 0% | 29 | 0% | 17 | 0% | 11 | 0% | 14 | 0% |

| Alberta | 208 | 0.02% | 27 | 0% | 48 | 0.01% | 33 | 0% | 10 | 0% | 3 | 0% |

| Manitoba | 198 | 0.02% | 15 | 0% | 7 | 0% | 13 | 0% | 8 | 0% | 13 | 0% |

| Saskatchewan | 115 | 0.01% | 5 | 0% | 2 | 0% | 7 | 0% | 6 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Nova Scotia |

46 | 0.01% | 23 | 0% | 15 | 0% | 3 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| New Brunswick |

22 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% | 2 | 0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

17 | 0% | 2 | 0% | N/A[n] | N/A | N/A[n] | N/A | N/A[n] | N/A | N/A[n] | N/A |

| Northwest Territories |

2[o] | 0.01% | 1[o] | 0.01% | 0[o] | 0% | 0[o] | 0% | 0[o] | 0% | 0[o] | 0% |

| Prince Edward Island |

1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Yukon | 1 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.02% | 1 | 0.01% |

| Canada | 6,774 | 0.04% | 2,148 | 0.02% | 1,465 | 0.01% | 1,400 | 0.01% | 1,016 | 0.01% | 2,342 | 0.03% |

Metropolitan areas

Canadian metropolitan areas with large populations of Indo−Canadians:

| Metro Area |

Province | 2016[36] | 2011[35] | 2006[34] | 2001[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | ||

| Toronto | Ontario | 643,370 | 10.97% | 572,250 | 10.36% | 484,655 | 9.56% | 345,855 | 7.44% |

| Vancouver | British Columbia |

243,140 | 10.02% | 217,820 | 9.55% | 181,895 | 8.67% | 142,060 | 7.22% |

| Calgary | Alberta | 90,625 | 6.59% | 66,640 | 5.56% | 48,270 | 4.51% | 31,585 | 3.35% |

| Edmonton | Alberta | 72,245 | 5.57% | 49,795 | 4.37% | 34,605 | 3.38% | 26,120 | 2.82% |

| Montréal | Quebec | 48,485 | 1.21% | 45,640 | 1.22% | 39,300 | 1.1% | 32,370 | 0.96% |

| Abbotsford− Mission |

British Columbia |

33,340 | 18.91% | 29,075 | 17.44% | 23,445 | 14.97% | 16,255 | 11.21% |

| Winnipeg | Manitoba | 30,795 | 4.04% | 19,850 | 2.78% | 13,545 | 1.97% | 11,520 | 1.74% |

| Ottawa− Gatineau |

Ontario | 28,945 | 2.23% | 25,550 | 2.1% | 21,170 | 1.9% | 17,510 | 1.67% |

| Hamilton | Ontario | 23,390 | 3.18% | 18,270 | 2.58% | 14,985 | 2.19% | 11,290 | 1.72% |

| Kitchener− Cambridge− Waterloo |

Ontario | 19,295 | 3.74% | 16,305 | 3.47% | 13,235 | 2.96% | 10,335 | 2.52% |

Toronto

Toronto has the largest Indo-Canadian population in Canada. Almost 51% of the entire Indo-Canadian community resides in the Greater Toronto Area. Most Indo-Canadians in the Toronto area live in Brampton, Markham, Scarborough, Etobicoke, and Mississauga. Indo-Canadians, particularly, Punjabi Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus, have a particularly strong presence in Brampton, where they represent about a third of the population (Most live in the northeastern and eastern portion of the city). The area is middle and upper middle class, home ownership is very high. The Indo-Canadians in this region are mostly of Punjabi, Telugu, Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Malayali and Goan origin. When compared to the Indo-Canadian community of Greater Vancouver, the Greater Toronto Area is home to a much more diverse community of Indians – both linguistically and religiously. Air India and Air Canada operates flights from Toronto Pearson International Airport back to India.

Indo-Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area have an average household income of $86,425, which is higher than the Canadian average of $79,102 but lower than the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area's average of $95,326. Indo-Canadian students are also well-represented in Toronto-area universities; despite Indo-Canadians making up 10% of the Toronto area's population, students of Indian origin (domestic and international combined) make up over 35% of Toronto Metropolitan University, 30% of York University, and 20% of the University of Toronto's student bodies, respectively.[91]

Canada's largest Hindu Mandir, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Toronto, as well as Canada's largest Sikh gurdwara, the Ontario Khalsa Darbar, are both located in the Greater Toronto Area. Both have been built by Canada's Indian community.

Greater Vancouver

Vancouver is home to the second largest Indo-Canadian population in Canada, with just over 20% of the entire Indo-Canadian community residing in the Lower Mainland.[92][93] The highest density concentrations of Indo-Canadians are found in Vancouver, Surrey, Burnaby, Richmond, Abbotsford and Delta. Recently, more Indians have been moving to other areas outside of Greater Vancouver. The city of Surrey has nearly 170,000 South Asians,[94] comprising 32% of the city's population.[95] The Punjabi Market neighbourhood of South Vancouver also has a particularly high concentration of Indian residents, shops and restaurants.[96]

A large majority of Indo-Canadians within Vancouver are of Punjabi Sikh origin.[97] However, there are also populations with other ethnic backgrounds including Indo-Fijians, Gujarati, Sindhi, Tamil, Bengali, and Goans.[98]

Indians from other countries

In addition to tracing their origin directly to the Indian subcontinent, many Indo-Canadians who arrive in Canada come from other parts of the world, as part of the global Indian diaspora.

| Region | Total Responses |

|---|---|

| Immigrant population | 474,530 |

| United States | 2,410 |

| Central and South America | 40,475 |

| Caribbean and Bermuda | 24,295 |

| Europe | 12,390 |

| **United Kingdom | 11,200 |

| **Other European | 1,190 |

| Africa | 45,530 |

| Asia | 332,150 |

| **West Central Asia and the Middle East | 6,965 |

| **Eastern Asia | 720 |

| **Southeast Asia | 4,260 |

| **South Asia | 320,200 |

| Oceania and other | 17,280 |

| Non-permanent residents | 9,950 |

Indians from Africa

Due to political turmoil and prejudice, many Indians residing in the African Great Lakes nations, such as Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and Angola left the region for Canada and other Western countries. A majority of Indo-Canadians from Southeast Africa are Ismaili Muslims or Gujarati Hindus, with significant numbers from South Africa as well.

Deepak Obhrai was the first Indo-African Canadian to become a member of parliament in Canada as well as the first Hindu to be appointed to the Queen's Privy Council for Canada, he was originally from Tanzania. He received the Pride of India award from the Indo-American Friends Group of Washington DC and Indo-American Business Chamber in a dinner ceremony held on Capitol Hill for his effort in strengthening ties between Canada and India.[100]

M.G. Vassanji, an award-winning novelist who writes on the plight of Indians in the region, is a naturalized Canadian of Indian descent who migrated from the Great Lakes.

The writer Ladis Da Silva (1920–1994) was a Zanzibar-born Canadian of Goan descent who wrote The Americanization of Goans.[101][page needed] He emigrated in 1968 from Kenya and was a prolific writer and social reformer, working with First Nations, Inuit and Senior Citizens in the Greater Toronto Area.[102]

Indians have also moved to Canada from Southern African nations such as Zambia, Malawi and South Africa for similar reasons. Examples of successful Indo-Canadians from this migratory stream are Suhana Meharchand and Nirmala Naidoo, television newscasters of Indian descent from South Africa, who currently work for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Indira Naidoo-Harris is another Canadian broadcaster who is of Indian descent from South Africa.

Two of the most high-profile Indo-Africans are CNN's Zain Verjee and Ali Velshi. Verjee was educated in Canada while Velshi's father Murad Velshi who immigrated from South Africa was the first MPP of Indian descent to sit in the Ontario legislature.

The most notable story of Indo-African immigration to Canada is set in the 1970s, when in 1972 50,000 Indian Ugandans were forced out of Uganda by the dictator Idi Amin, and were not permitted to return to India by the Indian government. Although on the brink of facing torture and imprisonment on a massive scale, the Aga Khan IV, leader of the Nizari Ismaili Community, specially negotiated his followers' safe departure from Uganda in exchange for all their belongings. He also negotiated their guaranteed asylum in Canada with Prime Minister and close friend Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

A notable descendant of Ugandan Indian settlement in Canada is Irshad Manji, an acclaimed advocate for secularism and reform in Islam. The community of Goans is also mainly from the African Great Lakes.

Indians from the Caribbean

Indo-Caribbean people are Caribbean people with roots in India.

The Indo-Caribbean Canadian community has developed a unique cultural blend of both Indian and Caribbean culture due to a long period of isolation from India, amongst other reasons. Some Indo-Caribbean Canadians associate themselves with the Indo-Canadian community. However, most associate with the Indo-Caribbean community or the wider Caribbean community or with both. Most mainly live within the Greater Toronto Area or Southern Ontario.

Indians from the UK and the US

Some Indians have immigrated from the United Kingdom and the United States due to both economic and family reasons. Indians move for economic prospects to Canada's economy and job market and have been performing well against many European and some American states. Lastly, individuals have decided to settle in Canada in order to reunite their families who may have settled in both the United States and the UK and not in Canada.

Indians from the Middle East

Many Indians have been moving from countries in the Middle East to North America.

Most Indian immigrants from the Middle East are Indian businessmen and professionals that worked in the Middle Eastern countries like the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. A key priority for these immigrants is educational opportunities for their children post-schooling. Many of these students have stayed back after graduation and started their families there.

Canadian cricketer Nikhil Dutta was born in Kuwait to Indian Bengali parents but grew up in Canada. He represents Canada national cricket team in ODIs and T20Is.

Indians from Oceania

Indians have long been settled in certain parts of Oceania, mainly on some islands in Fiji, where they comprise approximately 40% of Fiji's population. Since Fiji's independence, increased hostility between the Melanesian Fijian population and the Indo-Fijian population has led to several significant confrontations politically. Notably, since the two coups d'état of 1987 many Indo-Fijians are moving from Fiji to US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand due to political instability and ethnic conflict. A majority of the Indo-Fijian immigrants have settled in British Columbia and Alberta, with a significant population in the Greater Toronto Area as well, most of whom are Hindus, with a significant portion of Muslims. Other religions that are practised are Christianity and Sikhism. The Indo-Fijian population in Canada is not as diverse religiously as the general Indo-Canadian community. Indo-Fijians have established cultural centres and organisations in Vancouver, Surrey, Burnaby, Edmonton, Calgary and Toronto. The biggest Indo-Fijian cultural centre in Canada is the Fiji Sanatan Society of Alberta in Edmonton, built in 1984 by some of the first Indo-Fijian immigrants in Edmonton, it is officially a Hindu temple, but also hosts many community events.

Culture

Indo-Canadian culture is closely linked to each specific Indian group's religious, regional, linguistic and ethnic backgrounds. For instance, Northern Indian cultural practices and languages differ from those of Southern Indians, and the Hindu community's cultural practices differ from those of the Jain, Sikh, Muslim, Christian and Jewish communities due to differences in ethnicity, regional affiliation, religion and/or language. Such cultural aspects have been preserved fairly well due to Canada's open policy of multiculturalism, similar to the policy of multicultural diversity practised by the United States.

The cultures and languages of various Indian communities have been able to thrive in part due to the freedom of these communities to establish structures and institutions for religious worship, social interaction, and cultural practices. In particular, Punjabi culture and language have been reinforced in Canada through radio and television.

Alternatively, Indo-Canadian culture has developed its own identity compared to other non-resident Indians and from people in India. It is not uncommon to find youth uninterested with traditional Indian cultural elements and events, instead of identifying with mainstream North American cultural mores. However such individuals exist in a minority and there are many youth that maintain a balance between western and eastern cultural values, and occasionally fusing the two to produce a new product, such as the new generation of Bhangra incorporating hip-hop based rhythm. For instance, Sikh youth often mix in traditional Bhangra, which uses Punjabi instruments with hip hop beats as well as including rap with Black music entertainers. Notable entertainers include Raghav and Jazzy B.

Marriage

Marriage is an important cultural element amongst many Indo-Canadians, due to their Indian heritage and religious background.[103] Arranged marriage, which is still widely practised in India, is no longer widely practised among Canadian-born or naturalized Indians. However, marriages are sometimes still arranged by parents within their specific caste or Indian ethnic community. Since it may be difficult to find someone of the same Indian ethnic background with the desired characteristics, some Indo-Canadians now opt to use matrimonial services, including online services, in order to find a marriage partner. Marriage practices amongst Indo-Canadians are not as liberal as those of their Indian counterparts, with caste sometimes considered, but dowries almost non-existent.[103][citation needed]

In 2012, Mandeep Kaur wrote a PhD thesis titled "Canadian-Punjabi Philanthropy and its Impact on Punjab: A Sociological Study", which found that, compared to other ethnic groups, Indo-Canadians engage in more arranged marriages within ethnic communities and castes and engage in less dating; this is because these Indo-Canadian communities wish to preserve their cultural practices.[104]

Media

There are numerous radio programs that represent Indo-Canadian culture. One notable program is Geetmala Radio, hosted by Darshan and Arvinder Sahota (also longtime television hosts of Indo-Canadian program, Eye on Asia).

A number of Canadian television networks broadcast programming that features Indo-Canadian culture. One prominent multicultural/multireligious channel, Vision TV, presents a nonstop marathon of Indo-Canadian shows on Saturdays. These television shows often highlight Indo-Canadian events in Canada, and also show events from India involving Indians who reside there. In addition, other networks such as Omni Television, CityTV, and local community access channels also present local Indo-Canadian content, and Indian content from India.[citation needed]

In recent years,[when?] there has been an establishment of Indian television networks from India on Canadian television. Shan Chandrasehkhar, an established Indo-Canadian who pioneered one of the first Indo-Canadian television shows in Canada, made a deal with the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to allow Indian television networks based in India to send a direct feed to Canada. In doing so, he branded these channels under his own company known as the Asian Television Network. Since 1997, Indo-Canadians can subscribe to channels from India via purchasing TV channel packages from their local satellite/cable companies. Indo-Canadians view such networks as Zee TV, B4U, Sony Entertainment Television, and Aaj Tak to name a few. Goan communities are connected by a number of city-based websites that inform the community of local activities such as dances, religious services, and village feasts, that serve to connect the community to its rural origins in Goa.[105]

Radio stations in the Greater Toronto Area with Indo Canadian content include CJSA-FM broadcasting on 101.3FM. Another station is CINA broadcasting on AM 1650.

Major newspapers include Canindia News in Toronto & Montreal, The Asian Star and The Punjabi Star in Vancouver.

As of 2012, there are many Punjabi newspapers, most of which are published in Vancouver and Toronto. As of that year, 50 of them are weekly, two are daily, and others are monthly.[104]

By 2012, partly due to coverage of Air India Flight 182, coverage of Punjabi issues in The Globe and Mail, the Vancouver Sun, and other mainstream Canadian newspapers had increased.[104]

Film and television

- 7 to 11, Indian (2003) (English)

- 8 X 10 Tasveer (2009) (Hindi)

- Autograph (2010) (Bengali)

- Arasangam (2008) (Tamil)

- Asa Nu Maan Watna Da (2004) (Punjabi)

- Cooking with Stella (2009) (English)

- Dus (2005) (Hindi)

- Getting Married (English)

- Humko Deewana Kar Gaye (2006) (Hindi)

- Jatt and Juliet (2012) (Punjabi)

- Jee Aayan Nu (2003) (Punjabi)

- Jugni Back to Roots (2013) (Punjabi/English)

- Kismat Konnection (2008) (Hindi)

- Masala (1992) (English)

- Neal 'n' Nikki (2005) (Hindi)

- Panchathantiram (2006) (Tamil)

- Partition (2007) (English/Punjabi)

- Shakti: The Power (2002) (Hindi)

- Speedy Singhs (2011) (English)

- Sweet Amerika (2008) (English)

- Taal (1999) (Hindi)

- Thank You (2011) (Hindi)

- Tum Bin...Love Will Find a Way (2001) (Hindi)

- Two Countries (2016) (Malayalam)

- Antaheen (2009) (Bengali)

Notable people

See also

- Indian diaspora

- South Asian Canadians

- Indo-Canadians in British Columbia

- Indian Americans

- Canada–India relations

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g 2021 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Anglo-Indian" (3,340), "Bengali" (26,675), "Goan" (9,700), "Gujarati" (36,970), "Indian" (1,347,715), "Jatt" (22,785), "Kashmiri" (6,165), "Maharashtrian" (4,125), "Malayali" (12,490), "Punjabi" (279,950), "Tamil" (102,170), and "Telugu" (6,670).[1]

- ^ a b 1991 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (1,520), "East Indian" (379,280), "Punjabi" (27,300), and "Tamil" (15,695).[31]

- ^ a b 1996 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (3,790), "Goan" (4,415), "Gujarati" (2,155), "East Indian" (548,080), "Punjabi" (49,840), and "Tamil" (30,065).[32]

- ^ a b c 2001 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (7,020), "Goan" (3,865), "Gujarati" (2,805), "East Indian" (713,330), "Kashmiri" (480), "Punjabi" (47,155), and "Tamil" (39,075).[33]

- ^ a b c 2006 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (12,130), "Goan" (4,815), "Gujarati" (2,975), "East Indian" (962,670), "Kashmiri" (1,685), "Punjabi" (53,515), and "Tamil" (34,590).[34]

- ^ a b c 2011 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (17,960), "Goan" (5,125), "Gujarati" (5,890), "East Indian" (1,165,145), "Kashmiri" (2,125), "Punjabi" (76,150), and "Tamil" (48,965).[35]

- ^ a b c 2016 census: Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Bengali" (22,900), "Goan" (6,070), "Gujarati" (8,350), "East Indian" (1,374,715), "Kashmiri" (3,115), "Punjabi" (118,395), and "Tamil" (48,670).[36]

- ^ a b c When Grewall was nominated as a candidate for the CCF party in the Dewdney riding in 1956, this drew excitement. But, according to Barrett, Grewall faced open discrimination on the campaign trail. “The former mayor knew the risk he was taking and many people were surprised he took this risk to enter the race,” said Barrett. Barrett said Grewall overcame many racial insults along the way. “Every kid in the North Fraser, who thinks he or she is being discriminated against, should read the Grewall story and the challenges he faced.” Grewall was later found dead in a Seattle motel room with a gunshot wound to the head in July of 1957. He was 47 years of age.[63]

- ^ After losing his MLA bid in 1956 to SoCred Labor Minister Lyle Wicks, Grewal began receiving threats. Fires were set at his mills and his house was set ablaze. On July 17, 1957, while on a business trip, Grewall was found dead in a Seattle motel. He had been shot in the head. Although local police ruled it a suicide, Grewall's family believes he was a victim of foul play. Grewall was survived by his wife and three children, who left Mission City shortly after his death. Despite the suspicious circumstances of his death, Grewall's story is more notable for his legacy of community involvement than for his untimely demise.[60]

- ^ Including Jainism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Indigenous spirituality, and others not stated

- ^ a b The majority of Canadians of East Indian origin are either Sikh or Hindu. In 2001, 34% said they were Sikh, while 27% said they were Hindu. Another 17% were Muslim, 9% were Catholic and 7% belonged to a mainline Protestant denomination or other Christian grouping. On the other hand, relatively few Canadians of East Indian origin have no religious affiliation. That year, just 4% of people who reported East Indian origin said they had no religious affiliation, compared with 17% of the overall population.[7]

- ^ a b The question on knowledge of languages allows for multiple responses.

- ^ a b Combined responses of Hindi and Urdu as they form mutually intelligible registers of the Hindustani language.

- ^ a b c d Part of United Kingdom

References

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 17, 2022). "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 17, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table Canada [Country] Language". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 17, 2022). "2021 Census of Canada: Mother tongue by single and multiple mother tongue responses: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (May 10, 2023). "Religion by ethnic or cultural origins: Canada, provinces and territories and census metropolitan areas with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (November 15, 2023). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 16, 2007). "The East Indian community in Canada". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth. The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver: Three Generations Amid Tradition, Modernity, and Multiculturalism. University of Toronto Press, 2004. ISBN 0802086314, 9780802086310, p. 235. "3 'East Indians' refers to people whose roots are specifically in India. Although there is no country called East India, the British gave and used the term 'East India.' The British and Canadians commonly used the term 'East Indian' during the early period of Indian migration to Canada." and "4 'South Asians' is a very broad category as it refers to people originally in the geographical area of South Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. 'South Asians' also refers to Indians who have migrated to other parts of the world such as Fiji, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and East Africa."

- ^ a b c Sumartojo, Widyarini. 2012. "'My kind of Brown': Indo-Canadian youth identity and belonging in Greater Vancouver" (PhD thesis). Simon Fraser University. ID: etd7152. Archived 2014-10-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth. The Sikh Diaspora in Vancouver: Three Generations Amid Tradition, Modernity, and Multiculturalism. University of Toronto Press, 2004. ISBN 0802086314, 9780802086310. p. 236. See: "9 The term 'Indo-Canadians' came into use in the 1980s as a result of the Canadian government's policy and ideology of multiculturalism. It refers to Canadian-born people whose origins are on the Indian subcontinent." and "9 The term 'Indo-Canadians' came into use[...]"

- ^ Ames, Michael M. & Joy Inglis. 1974. "Conflict and Change in British Columbia Sikh Family Life" (Archived 2015-07-11 at the Wayback Machine). In British Columbia Studies, Vol. 20. Winter 1973-1974. CITED: p. 19.

- ^ ("The East Indian Community in Canada". Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)). Statistics Canada. Retrieved on November 10, 2014. "That year, roughly half of all foreign-born Canadians of East Indian origin were from India, while smaller numbers were from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, as well as East Africa" - ^ Sharma, Kavita A. The Ongoing Journey: Indian Migration to Canada. Creative Books, 1997. ISBN 8186318399, 9788186318393. p. 16. "Notes 1 Indians are variously designated as East Indians, South Asians and Indo- Canadians. The terms are used interchangeably throughout this book except that 'Indo-Canadian' has been used for only those Indians who have acquired Canadian citizenship".

- ^ Mani, Priya S. (University of Manitoba). "Methodological Dilemmas Experienced in Researching Indo-Canadian Young Adults’ Decision-Making Process to Study the Sciences." International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (2) June 2006. PDF p. 2/14. "The term South Asian refers to the Statistics Canada classification, which includes young adults who identify as Sikh, Hindu, or Muslim religious background (Statistics Canada, 2001). In this article, the term Indo-Canadian refers to children of South Asian immigrants."

- ^ a b c Henderson, Martha L. Geographical Identities of Ethnic America: Race, Space, and Place. University of Nevada Press, 2002. ISBN 0874174872, 9780874174878. p. 65.

- ^ "South Asians" (Archived November 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine). The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved on November 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Census of Canada 1870-71 = Recensement du Canada 1870-71 v. 1". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 11, 2017). "Canada Year Book 1913". www12.statcan.gc.ca. pp. 102–112. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Lal, Brij (1976). "East Indians in British Columbia 1904-1914 : an historical study in growth and integration". www.open.library.ubc.ca. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Hugh (1984). "The East Indians in Canada" (PDF). Canada's Ethnic Groups. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Sixth census of Canada,1921. v. 1. Population: number, sex and distribution, racial origins, religions". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Seventh census of Canada, 1931. Vol. 2. Population by areas". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Eighth census of Canada,1941 = Huitième recensement du Canada Vol. 2. Population by local subdivisions". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Eighth census of Canada,1941 = Huitième recensement du Canada Vol. 4. Cross-classifications, interprovincial migration, blind and deaf-mutes". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Ninth census of Canada, 1951 = Neuvième recensement du Canada Vol. 1. Population: general characteristics". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1961 Census of Canada : population : vol. I - part 2 = 1961 Recensement du Canada : population : vol. I - partie 2. Ethnic groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1971 Census of Canada : population : vol. I - part 3 = Recensement du Canada 1971 : population : vol. I - partie 3. Ethnic Groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1981 Census of Canada : volume 1 - national series : population = Recensement du Canada de 1981 : volume 1 - série nationale : population. Ethnic origin". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Census Canada 1986 Profile of ethnic groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1986 Census of Canada: Ethnic Diversity In Canada". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1991 Census: The nation. Ethnic origin". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (June 4, 2019). "Data tables, 1996 Census Population by Ethnic Origin (188) and Sex (3), Showing Single and Multiple Responses (3), for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1996 Census (20% Sample Data)". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (December 23, 2013). "Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (May 1, 2020). "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (January 23, 2019). "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (June 17, 2019). "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Buchignani, Norman. [2010 May 12] 2020 February 10. "South Asian Canadians." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Ottawa: Historica Canada.

- ^ a b Singh, Khushwant (February 26 – March 12, 1961). "The Ghadr Rebellion". Illustrated Weekly of India: Feb 26 – Mar 12. Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Johnston, Hugh. [2006 February 7] 2016 May 19. "Komagata Maru." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Ottawa: Historica Canada.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "SOME SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS IN SIKH-CANADIAN HISTORY" (Archive). ExplorAsian. Retrieved on November 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Walton-Roberts, Margaret. 1998. "Three Readings of the Turban: Sikh Identity in Greater Vancouver" (Archive). In Urban Geography, Vol. 19: 4, June. - DOI 10.2747/0272-3638.19.4.311 - Available at Academia.edu and at ResearchGate. p. 316.

- ^ "FIRST SIKH TEMPLE IN NORTH AMERICA". March 10, 2021.

The first Sikhs came to Golden about 1902, arriving to work in the sawmill of the Columbia River Lumber Company. When the Sikhs arrived in Golden the community was in its infancy and the sawmill had recently opened. The Columbia River Lumber Company recognized the value of these tall strong men and had no problem with the men. They hired them to work in the lumberyard, planer, and sawmill. The first documented proof that we have of South Asians of the Sikh faith being residents of Golden is a copy of a telegram sent to G.T. Bradshaw, Chief of Police, New Westminster from Colin Cameron, Chief of Police, Golden, BC on July 20, 1902. It was sent collect and reads: Geha Singh of Golden sent a telegram to Santa Singh care of Small and Bucklin for one thousand dollars.

- ^ a b "Sikhs celebrate history in Golden". April 26, 2018.

The original temple in Golden sat on a corner of a lot, in the south western area of town at the end of the street looking toward where Rona is now. The largest influx of men came from South Asia around 1905, which would be the time period that the temple in Golden would have began services. In 1926, a fire burned the timber limits of the Columbia River Lumber Company, where the South Asian men worked.

- ^ a b "Golden's Sikh heritage recognized on new Stop of Interest sign". November 9, 2016.

"We acknowledge the Gurdwara in Golden as the first in B.C., and quite likely the first in North America," said Pyara Lotay, on behalf of the local Sikh community. "We thank the B.C. government for recognizing Golden's Sikh pioneers and their place of worship with this Stop of Interest."

- ^ a b "Golden Gurdwara is recognized for its historical significance". June 7, 2017.

The original temple sat on the corner of a lot, which is now owned by Gurmit Manhas, at the end of the street past the School Board Office looking towards the Rona. Plans are being put together to erect a kiosk there that would share information about the original building, the first South Asian people to Canada, the importance of the Gurdwara to the Sikh people and the history of why they left and what brought them back. The largest influx of men came from South Asia in about 1905-06, which would be the time period that the Temple would have begun services. In 1926 a fire burned the timber limits of the Columbia River Lumber Company, where all the South Asian men worked and the men left for the coast having no work to do. When the forest started to grow back the men came back and soon it was necessary to build the present Gurdwara on 13th Street South.

- ^ a b "First Sikh Temple • Vancouver Heritage Foundation".

- ^ "New Westminster Sikh temple celebrates 100-year anniversary". March 3, 2019.

The Gurdwara Sahib Sukh Sagar is one of the oldest Sikh temples in the country and its members are celebrating the milestone anniversary by reflecting on its historic significance to the local Sikh community. The temple was actually founded more than 100 years ago when a pioneering Sikh named Bhai Bishan Singh bought a house next door to where the building is now. Singh paid $250 for the house, which served as a place of worship until the congregation grew too large. In 1919, Singh bought the neighbouring lot at 347 Wood Street and the Gurdwara Sahib Sukh Sagar was born.

- ^ "New Westminster Sikh temple welcomes community to celebrate its centennial anniversary". February 27, 2019.

The Khalsa Diwan Society New Westminster is inviting community members to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Gurdwara Sahib Sukh Sagar in Queensborough. Since opening in 1919, the temple has become an integral part of the Queensborough and New Westminster communities, and has provided a place for Sikhs from New Westminster and the Lower Mainland to gather and to worship. "It is starting up on Thursday and it will be four days, with the main event on Sunday. It's open to anyone within the community – in Queensborough and in New West. It's to show support, learn about each other and the heritage," said Jag Sall, a member of the committee that's organizing the celebration. "I don't think a lot of people know that the Sikh community has been in Queensborough for over 100 years, and/or the gurdwara itself has been there that long. Not just the Sikh community, but other communities in Queensborough have been living there for a century."

- ^ "The Gurdwara of New West Shares a Century of Stories". January 23, 2020.

Every Sunday in 1919, the Sikhs of Queensborough on the Fraser River would stroll over to the house of Bhai Bishan Singh for worship. Singh, like many Punjabi immigrants, settled in the New Westminster neighbourhood because he worked upriver at a sawmill. A devout Sikh, he had the holy scripture installed in his home, the Guru Granth Sahib. Singh was a bachelor and gave much of his earnings to the local Khalsa Diwan Society, which in 1908 had built B.C.'s first gurdwara, the Sikh place of worship, in Vancouver. In March 1919, Singh helped the Sikhs of New Westminster start a gurdwara of their own. For $250, Singh bought the property next door and donated it to the society. Later, he would donate his house as well.

- ^ "Paldi Sikh Temple in Cowichan celebrating 100 years". June 26, 2019.

The town's cultural centres were the Japanese community hall and the Sikh Temple, which officially opened July 1, 1919, to coincide with Dominion Day.

- ^ "Sikh temple celebrates 100 years of acceptance in Vancouver Island ghost town". June 29, 2019.

Paldi's Gurdwara was built in 1919 and soon became one of the most important fixtures of the community, even surviving several town fires.

- ^ "THE FOUNDING OF PALDI".

In 1919, Mayo built a Sikh temple, or a gurdwara.

- ^ "PALDI: Town soaked in Sikh History".