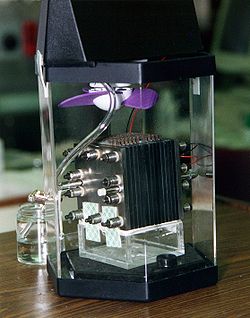

Direct methanol fuel cell

Direct methanol fuel cells or DMFCs are a subcategory of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells in which methanol is used as the fuel and a special proton-conducting polymer as the membrane (PEM). Their main advantage is low temperature operation and the ease of transport of methanol, an energy-dense yet reasonably stable liquid at all environmental conditions.

Whilst the thermodynamic theoretical energy conversion efficiency of a DMFC is 97%;[1] as of 2014 the achievable energy conversion efficiency for operational cells attains 30%[2] – 40%.[3] There is intensive research on promising approaches to increase the operational efficiency.[4]

A more efficient version of a direct fuel cell would play a key role in the theoretical use of methanol as a general energy transport medium, in the hypothesized methanol economy.

The cell

In contrast to indirect methanol fuel cells, where methanol is reacted to hydrogen by steam reforming, DMFCs use a methanol solution (usually around 1M, i.e. about 3% in mass) to carry the reactant into the cell; common operating temperatures are in the range 50 to 120 °C (122 to 248 °F), where high temperatures are usually pressurized. DMFCs themselves are more efficient at high temperatures and pressures, but these conditions end up causing so many losses in the complete system that the advantage is lost;[5] therefore, atmospheric-pressure configurations are currently preferred.

Because of the methanol cross-over, a phenomenon by which methanol diffuses through the membrane without reacting, methanol is fed as a weak solution: this decreases efficiency significantly, since crossed-over methanol, after reaching the air side (the cathode), immediately reacts with air; though the exact kinetics are debated, the result is a reduction of the cell voltage. Cross-over remains a major factor in inefficiencies, and often half of the methanol is lost to cross-over. Methanol cross-over and/or its effects can be alleviated by (a) developing alternative membranes (e.g.[6][7]), (b) improving the electro-oxidation process in the catalyst layer and improving the structure of the catalyst and gas diffusion layers (e.g.[8] ), and (c) optimizing the design of the flow field and the membrane electrode assembly (MEA) which can be achieved by studying the current density distributions (e.g.[9] ).

Other issues include the management of carbon dioxide created at the anode, the sluggish dynamic behavior, and the ability to maintain the solution water.

The only waste products with these types of fuel cells are carbon dioxide and water.

Application

Current DMFCs are limited in the power they can produce, but can still store a high energy content in a small space. This means they can produce a small amount of power over a long period of time. This makes them ill-suited for powering large vehicles (at least directly), but ideal for smaller vehicles such as forklifts and tuggers[10] and consumer goods such as mobile phones, digital cameras or laptops. Military applications of DMFCs are an emerging application since they have low noise and thermal signatures and no toxic effluent. These applications include power for man-portable tactical equipment, battery chargers, and autonomous power for test and training instrumentation. Units are available with power outputs between 25 watts and 5 kilowatts with durations up to 100 hours between refuelings. Especially for power output up to 0.3 kW the DMFC is suitable. For a power output of more than 0.3 kW the indirect methanol fuel cell presents a higher efficiency and is more cost-efficient.[11] Freezing of the liquid methanol-water mixture in the stack at low ambient temperature can be problematic for the membrane of DMFC (in contrast to indirect methanol fuel cell).

Methanol

Methanol is a liquid from −97.6 to 64.7 °C (−143.7 to 148.5 °F) at atmospheric pressure. The volumetric energy density of methanol is an order of magnitude greater than even highly compressed hydrogen, about two times greater than liquid hydrogen and 2.6 times higher than lithium-ion batteries.[when?] The energy density per mass is a tenth of that of hydrogen, but 10 times higher than that of lithium-ion batteries.[12]

Methanol is slightly toxic and highly flammable. However, the International Civil Aviation Organization's (ICAO) Dangerous Goods Panel (DGP) voted in November 2005 to allow passengers to carry and use micro fuel cells and methanol fuel cartridges when aboard airplanes to power laptop computers and other consumer electronic devices. On September 24, 2007, the US Department of Transportation issued a proposal to allow airline passengers to carry fuel cell cartridges on board.[13] The Department of Transportation issued a final ruling on April 30, 2008, permitting passengers and crew to carry an approved fuel cell with an installed methanol cartridge and up to two additional spare cartridges.[14] It is worth noting that 200 ml maximum methanol cartridge volume allowed in the final ruling is double the 100 ml limit on liquids allowed by the Transportation Security Administration in carry-on bags.[15]

Reaction

The DMFC relies upon the oxidation of methanol on a catalyst layer to form carbon dioxide. Water is consumed at the anode and produced at the cathode. Protons (H+) are transported across the proton exchange membrane - often made from Nafion - to the cathode where they react with oxygen to produce water. Electrons are transported through an external circuit from anode to cathode, providing power to connected devices.

The half-reactions are:

| Equation | |

|---|---|

| Anode | oxidation |

| Cathode | reduction |

| Overall reaction | redox reaction |

Methanol and water are adsorbed on a catalyst usually made of platinum and ruthenium particles, and lose protons until carbon dioxide is formed. As water is consumed at the anode in the reaction, pure methanol cannot be used without provision of water via either passive transport such as back diffusion (osmosis), or active transport such as pumping. The need for water limits the energy density of the fuel.

Platinum is used as a catalyst for both half-reactions. This contributes to the loss of cell voltage potential, as any methanol that is present in the cathode chamber will oxidize. If another catalyst could be found for the reduction of oxygen, the problem of methanol crossover would likely be significantly lessened. Furthermore, platinum is very expensive and contributes to the high cost per kilowatt of these cells.

During the methanol oxidation reaction carbon monoxide (CO) is formed, which strongly adsorbs onto the platinum catalyst, reducing the number of available reaction sites and thus the performance of the cell. The addition of other metals, such as ruthenium or gold, to the platinum catalyst tends to ameliorate this problem. In the case of platinum-ruthenium catalysts, the oxophilic nature of ruthenium is believed to promote the formation of hydroxyl radicals on its surface, which can then react with carbon monoxide adsorbed on the platinum atoms. The water in the fuel cell is oxidized to a hydroxy radical via the following reaction: H2O → OH• + H+ + e−. The hydroxy radical then oxidizes carbon monoxide to produce carbon dioxide, which is released from the surface as a gas: CO + OH• → CO2 + H+ + e−.[16]

Using these OH groups in the half reactions, they are also expressed as:

| Equation | |

|---|---|

| Anode | oxidation |

| Cathode | reduction |

| Overall reaction | redox reaction |

Cross-over current

Methanol on the anodic side is usually in a weak solution (from 1M to 3M), because methanol in high concentrations has the tendency to diffuse through the membrane to the cathode, where its concentration is about zero because it is rapidly consumed by oxygen. Low concentrations help in reducing the cross-over, but also limit the maximum attainable current.

The practical realization is usually that a solution loop enters the anode, exits, is refilled with methanol, and returns to the anode again. Alternatively, fuel cells with optimized structures can be directly fed with high concentration methanol solutions or even pure methanol.[17]

Water drag

The water in the anodic loop is lost because of the anodic reaction, but mostly because of the associated water drag: every proton formed at the anode drags a number of water molecules to the cathode. Depending on temperature and membrane type, this number can be between 2 and 6.

Ancillary units

A direct methanol fuel cell is usually part of a larger system including all the ancillary units that permit its operation. Compared to most other types of fuel cells, the ancillary system of DMFCs is relatively complex. The main reasons for its complexity are:

- providing water along with methanol would make the fuel supply more cumbersome, so water has to be recycled in a loop;

- CO2 has to be removed from the solution flow exiting the fuel cell;

- water in the anodic loop is slowly consumed by reaction and drag; it is necessary to recover water from the cathodic side to maintain steady operation.

See also

References

- ^ Umit B. Demirci (2007). "Review: Direct liquid-feed fuel cells: Thermodynamic and environmental concerns". Journal of Power Sources. 169. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.03.050.

- ^ Ibrahim Dincer, Calin Zamfirescu (2014). "4.4.7 Direct Methanol Fuel Cells". Advanced Power Generation Systems. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-383860-5.00004-3.

- ^ Keith Scott, Lei Xing (2012). "3.1 Introduction". Fuel Cell Engineering. p. 147. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386874-9.00005-1.

- ^ Pasha Majidi; et al. (1 May 2016). "Determination of the efficiency of methanol oxidation in a direct methanol fuel cell". Electrochimica Acta. 199.

- ^ Dohle, H.; Mergel, J. & Stolten, D.: Heat and power management of a direct-methanol-fuel-cell (DMFC) system, Journal of Power Sources, 2002, 111, 268-282.

- ^ Wei, Yongsheng; et al. (2012). "A novel membrane for DMFC – Na2Ti3O7 Nanotubes/Nafion composite membrane: Performances studies". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 37 (2): 1857–1864. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.08.107.

- ^ "Safe space: improving the "clean" methanol fuel cells using a protective carbon shell". Bioengineer.org. 4 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Matar, Saif; Hongtan Liu (2010). "Effect of cathode catalyst layer thickness on methanol cross-over in a DMFC". Electrochimica Acta. 56 (1): 600–606. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2010.09.001.

- ^ Almheiri, Saif; Hongtan Liu (2014). "Separate measurement of current density under land and channel in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells". Journal of Power Sources. 246: 899–905. Bibcode:2014JPS...246..899A. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.08.029.

- ^ Tenn. Nissan Plant to Use Methanol to Cut Costs by ABC News.

- ^ Simon Araya, Samuel; Liso, Vincenzo; Cui, Xiaoti; Li, Na; Zhu, Jimin; Sahlin, Simon Lennart; Jensen, Søren Højgaard; Nielsen, Mads Pagh; Kær, Søren Knudsen (2020). "A Review of The Methanol Economy: The Fuel Cell Route". Energies. 13 (3): 596. doi:10.3390/en13030596.

- ^ Edwards, P.P.; Kuznetsov, V.L.; David, W.I.F.; Brandon, N.P. (December 2008). "Hydrogen and fuel cells: Towards a sustainable energy future". Energy Policy. 36 (12): 4356–4362. Bibcode:2008EnPol..36.4356E. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.036.

- ^ US Department of Transportation moves to approve fuel cells for aircraft use Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, by FuelCellToday.

- ^ Hazardous Materials: Revision to Requirements for the Transportation of Batteries and Battery-Powered Devices; and Harmonization with the United Nations Recommendations, International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code, and International Civil Aviation Organization's Technical Instructions Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, by the US department of transportation.

- ^ 3-1-1 Gains International Acceptance Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, by the US transport security administration.

- ^ Motoo, S.; Watanabe, M. (1975). "Electrolysis by Ad-Atoms Part II. Enhancement of the Oxidation of Methanol on Platinum by Ruthenium Ad-Atoms". Electrochemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry. 60: 267–273.

- ^ Li, Xianglin; Faghri. "Amir". Journal of Power Sources. 226: 223–240. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.10.061.

Further reading

- Merhoff, Henry and Helbig, Peter. Development and Fielding of a Direct Methanol Fuel Cell; ITEA Journal, March 2010