Death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way.[1] It is distinct from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convention requires that prisoners must be moved away from a danger zone such as an advancing front line, to a place that may be considered more secure. It is not required to evacuate prisoners who are too unwell or injured to move. In times of war, such evacuations can be difficult to carry out.

Death marches usually feature harsh physical labor and abuse, neglect of prisoner injury and illness, deliberate starvation and dehydration, humiliation, torture, and execution of those unable to keep up the marching pace. The march may end at a prisoner-of-war camp or internment camp, or it may continue until all those who are forced to march are dead.

Notable death marches

Jingkang incident

In 1127, during the Jin–Song Wars, the forces of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty besieged and sacked the Imperial palaces in Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng), the capital of the Han-led Song dynasty. The Jin forces captured the Song ruler, Emperor Qinzong, along with his father, the retired Emperor Huizong, as well as many members of the imperial family and officials of the Song imperial court. According to The Accounts of Jingkang, Jin troops looted the imperial library and palace. Jin troops also abducted all the female servants and imperial musicians. The imperial family was abducted and their residences were looted. Facing the prospect of captivity and enslavement by the Jurchens, numerous palace women chose to take their own lives. The remaining captives, over 14,000 people, were forced to march alongside the seized assets towards the Jin capital. Their entourage – almost all the ministers and generals of the Northern Song dynasty – suffered from illness, dehydration, and exhaustion, and many never made it. Upon arrival, each person had to go through a ritual where the person had to be naked and wearing only sheep skins.[2]

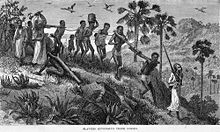

African slave trade

Forced marches were utilized against slaves who were bought or captured by slave traders in Africa. They were shipped to other lands as part of the East African slave trade with Zanzibar and the Atlantic slave trade. Sometimes, the merchants shackled the slaves and provided insufficient food. Slaves who became too weak to walk were frequently killed or left to die.[3][4]

David Livingstone wrote of the East African slave trade:

We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path. [Onlookers] said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer.[5]

Forced displacement of Native Americans

As part of Native American removal in the United States, approximately 6,000 Choctaw were forced to leave Mississippi and move to the newly forming Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) in 1831. Only about 4,000 Choctaw arrived in 1832.[6] In 1836, after the Creek War, the United States Army deported 2,500 Muskogee from Alabama in chains as prisoners of war.[7] The rest of the tribe (12,000) followed, deported by the Army. Upon arrival to Indian Territory, 3,500 died of infection.[8] In 1838, the Cherokee nation was forced by order of President Andrew Jackson to march westward towards Indian Territory. This march became known as the Trail of Tears. An estimated 4,000 men, women, and children died during relocation.[9] When the Round Valley Indian Reservation was established, the Yuki people (as they came to be called) of Round Valley were forced into a difficult and unusual situation. Their traditional homeland was not completely taken over by settlers as in other parts of California. Instead, a small part of it was reserved especially for their use as well as the use of other Indians, many of whom were enemies of the Yuki. The Yuki had to share their home with strangers who spoke other languages, lived with other beliefs, and used the land and its products differently. Indians came to Round Valley as they did to other reservations– by force. The word "drive," widely used at the time, is descriptive of the practice of "rounding up" Indians and "driving" them like cattle to the reservation where they were "corralled" by high picket fences. Such drives took place in all weathers and seasons, and the elderly and sick often did not survive.[citation needed] During the Long Walk of the Navajo in August 1863, all Konkow Maidu were to be sent to the Bidwell Ranch in Chico and then be taken to the Round Valley Reservation at Covelo in Mendocino County. Any Indians remaining in the area were to be shot. Maidu were rounded up and marched under guard west out of the Sacramento Valley and through to the Coastal Range. 461 Native Americans started the trek, 277 finished.[10] They reached Round Valley on 18 September 1863. After the Yavapai Wars, 375 Yavapai perished during deportations out of 1,400 remaining Yavapai.[11][12]

Congo Free State

King Leopold II sanctioned the creation of "child colonies" in his Congo Free State which had orphaned Congolese kidnapped and sent to schools operated by Catholic missionaries in which they would learn to work or be soldiers; these were the only schools funded by the state. More than 50% of the children sent to the schools died of disease, and thousands more died in the forced marches into the colonies. In one such march, 108 boys were sent over to a mission school and only 62 survived, eight of whom died a week later.[13]

Dungan Revolt (1862–1877)

During the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877), 700,000 to 800,000 Hui Muslims from Shaanxi were deported to Gansu, in a process in which most were killed along the way from thirst, starvation, and massacres by the militia escorting them, with only a few thousand surviving.[14]

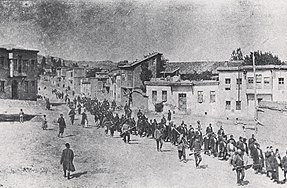

Armenian Genocide

The Armenian genocide resulted in the death of up to 1,500,000 people from 1915 to 1918. Under the cover of World War I, the Young Turks sought to cleanse Turkey of its Armenian population. As a result, much of the Armenian population was exiled from large parts of Western Armenia and forced to march to the Syrian desert.[15] Many were raped, tortured, and killed on their way to the 25 concentration camps set up in the Syrian desert. The most infamous camps were the Deir ez-Zor camps, where an estimated 150,000 Armenians were killed.[16]

World War I

Grand Duke Nicolas (who was still commander-in-chief of the Western forces), after suffering serious defeats at the hands of the German army, decided to implement the decrees for the German Russians living under his army's control, principally in the Volhynia province. The lands were to be expropriated, and the owners deported to Siberia. The land was to be given to Russian war veterans once the war was over. In July 1915, without prior warning, 150,000 German settlers from Volhynia were arrested and shipped to internal exile in Siberia and Central Asia. (Some sources indicate that the number of deportees reached 200,000). Ukrainian peasants took over their lands. While precise figures remain elusive, estimates suggest that the mortality rate associated with these deportations ranged from 30% to 50%, translating to a death toll between 63,000 and 100,000 individuals.[citation needed]

In the eastern part of Russian Turkestan, after the suppression of the Urkun uprising against the Russian Empire tens of thousands of surviving Kyrgyz and Kazakhs fled toward China. In the Tien-Shan mountains, thousands died in mountain passes over 3,000 meters high.[17]

World War II

During World War II, death marches of POWs occurred in both German-occupied Europe and the Japanese colonial empire. Death marches of those held in Nazi concentration camps were common in the later stages of the Holocaust as Allied forces closed in on the camps. One infamous death march occurred in January 1945, as the Soviet Red Army advanced on German-occupied Poland. Nine days before the Red Army arrived at the Auschwitz concentration camp, the Schutzstaffel marched nearly 60,000 prisoners out of the camp towards Wodzisław Śląski, where they were put on freight trains to other camps. Approximately 15,000 prisoners died on the way.[18][19] The death marches were judged during the Nuremberg trials to be a crime against humanity.[citation needed] On the Eastern Front, death marches were amongst the forms of German atrocities committed against Soviet prisoners of war.

During the NKVD prisoner massacres in 1941, NKVD personnel led prisoners on death marches to various locations in Eastern Europe; upon arriving to pre-designated execution sites, the survivors were summarily executed. After the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943, numerous German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union were subject to death marches; after enduring a period of captivity near Stalingrad, they were sent by the Soviet authorities on a "death march across the frozen steppe" to labor camps elsewhere in the Soviet Union.[20][21]

The Brno death march during the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia occurred in May 1945. The Bleiburg repatriations also occurred in May 1945 (during the last days of World War II and after), a total of 280,000 Croats,[22] were involved in the Independent State of Croatia evacuation to Austria. Mostly Ustaše and the Croatian Home Guard, but also civilians and refugees, tried to flee the Yugoslav Partisans and the Red Army, and marched northwards through Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia to Allied-occupied Austria. However, the British refused to accept their surrender and directed them to surrender to Yugoslav forces, who subjected them to death marches back to Yugoslavia, resulting in the death of 70–80,000 people.[23]

In the Pacific theatre, the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces conducted death marches of Allied POWs, including the 1942 Bataan Death March and the 1945 Sandakan Death Marches. The former forcibly transferred 60–80,000 POWs to Balanga, resulting in the deaths of 2,500–10,000 Filipino and 100–650 American POWs, while the latter caused the deaths of 2,345 Australian and British POWs, of which only 6 survived. Lieutenant-General Masaharu Homma was charged with failure to control his troops in 1945 in connection with the Bataan Death March.[24][25] Both the Bataan and Sandakan death marches were judged by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East to be war crimes.[citation needed]

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union refers to the forced transfer of various groups from the 1930s up to the 1950s ordered by Joseph Stalin and may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population (often classified as "enemies of workers"), deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite directions to fill the ethnically cleansed territories. Soviet archives documented 390,000[26] deaths during kulak forced resettlement and up to 400,000 deaths of persons deported to forced settlements in the Soviet Union during the 1940s;[27] however Steven Rosefield and Norman Naimark put overall deaths closer to some 1 to 1.5 million perishing as a result of the deportations — of those deaths, the deportation of Crimean Tatars and the deportation of Chechens were recognized as genocides by Ukraine and the European Parliament respectively.[28][29][30][31]

Lydda Death March

During the 1948 Palestine war, 50,000-70,000 Palestinians were expelled from the cities of Lydda (also spelled Lod) and Ramla by the Israeli military. Occurring as a part of the broader 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight and the Nakba, the operation is widely considered to have been an instance of ethnic cleansing.[32] Ramla'a residents were expelled by bus[33] but Lydda's residents had to walk 10-15 miles to meet up with the lines of the Arab Legion.[34] Many people died from the heat, thirst, and exhaustion on the journey[35] and the event has come to be known as the Lydda Death March.[36][37][38][39]

Reports vary regarding how many died. Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref estimated 500 died in the expulsion from Lydda, and that 350 of that number died from thirst and exhaustion.[40][41] Nur Masalha estimated 350 deaths in the "expulsion and forced march" from Lydda.[42][43] Historian Benny Morris has written that it was a "handful and perhaps dozens."[44] Glubb Pasha wrote that "nobody will ever know how many children died."[45] Nimr al Khatib estimated that 335 died. Historian Benny Morris calls this number "certainly an exaggeration", while historian Michael Palumbo called Khatib's estimate "a very conservative figure."[46][47]

Korean War

During the Korean War, in the winter of 1951, 200,000 South Korean National Defense Corps soldiers were forcibly marched by their commanders, and 50,000 to 90,000 soldiers starved to death or died of disease during the march or in the training camps.[48] This incident is known as the National Defense Corps incident. During the Korean War, prisoners who were held by the North Koreans underwent what became known as the "Tiger Death March". The march occurred while North Korea was being overrun by United Nations forces. As North Korean forces retreated to the Yalu River on the border with China, they evacuated their prisoners with them. On 31 October 1950, some 845 prisoners, including about eighty non-combatants, left Manpo and went upriver, arriving in Chunggang on 8 November 1950. A year later, fewer than 300 of the prisoners were still alive. The march was named after the brutal North Korean colonel who presided over it, his nickname was "The Tiger". Among the prisoners was George Blake, an MI6 officer who had been stationed in Seoul. While he was being held as a prisoner, he became a KGB double agent.[49]

Phnom Penh

The Khmer Rouge marked the beginning of their rule with the forced evacuation of various cities including Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

See also

- Carolean Death March (1718–1719)

- Samsun deportations (1921–1922)

- March of the Living

- Armenian genocide

- Assyrian genocide

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

- Forced displacement

- Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

- List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

References

- ^ "Definition of DEATH MARCH". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ "The Accounts of Jingkang" (靖康稗史箋證) 「临行前俘虏的总数为14000名,分七批押至北方,其中第一批宗室贵戚男丁二千二百余人,妇女三千四百余人」,靖康二年三月二十七日,「自青城国相寨起程,四月二十七日抵燕山,存妇女一千九百余人。」("There were 14,000 captives divided into seven groups when the march commenced. The first group, composed of imperial family members and nobles, contained 2,200 males and 3,400 females and departed on the 27th day of the third month from the Qingcheng stockade. When it arrived in Yanshan on the 27th day of the following month, just over 1,900 females remained.")

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007). Encyclopedia of the Middle Passage. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0313334801. OCLC 230753290.

- ^ Friedman, Saul S (2000). Jews and the American Slave Trade. Transaction Publishers. p. 232. ISBN 978-1412826938.

- ^ Livingstone, David (2006). The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death. Echo Library. p. 46. ISBN 184637555X.

- ^ "Trail of Tears". Choctaw Nation. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

- ^ Foreman, Grant (1974) [1932]. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. University of Oklahoma Press. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012.

- ^ "Creeks". Everyculture.com.

- ^ Marshall, Ian (1998). Story line: exploring the literature of the Appalachian Trail (Illustrated ed.). University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0813917986.

- ^ Dizard, Jesse A. (2016). "Nome Cult Trail". ARC-GIS storymap. technical assistance from Dexter Nelson and Cathie Benjamin. Department of Anthropology, California State University, Chico – via Geography and Planning Department at CSU Chico.

- ^ Immanuel, Marc (21 April 2017). "The Forced Relocation of the Yavapai".

- ^ Mann, Nicholas (2005). Sedona, Sacred Earth: A Guide to the Red Rock County. Light Technology Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1622336524.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold's Ghost A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Mariner Books. p. 135.

- ^ "回族 – 广西民族报网". Archived from the original on 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "Exiled Armenians Starve in the Desert". The New York Times. Boston. August 8, 1916.

- ^ Winter, Jay, ed. (2004). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511497605. ISBN 978-0521829588.

- ^ Bruce Pannier (2 August 2006). "Kyrgyzstan: Victims Of 1916 'Urkun' Tragedy Commemorated". RFE/RL.

- ^ "Death marches". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-08-25.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (May 1993). Atlas of the Holocaust (Revised and Updated ed.). William Morrow & Company. ISBN 0688123643. (map of forced marches)

- ^ Beevor, Antony (1998). "25 'The Sword of Stalingrad'". Stalingrad. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0141032405.

- ^ Griess, Thomas E. (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean (The West Point Military History Series). West Point Military Series; First Printing edition. p. 134. ISBN 978-0757001604.

- ^ Corsellis, John, & Marcus Ferrar. 2005. Slovenia 1945: Memories of Death and Survival After World War II. London: I.B. Tauris, p. 204.

- ^ Vuletić, Dominik (December 2007). "Kaznenopravni i povijesni aspekti bleiburškog zločina". Lawyer (in Croatian). 41 (85). Zagreb, Croatia: Pravnik: 125–150. ISSN 0352-342X. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Steiner, K., Lael, R. R., & Taylor, L. (1985). War Crimes and Command Responsibility: From the Bataan Death March to the MyLai Massacre. Pacific Affairs, 58(2), 293.

- ^ Maguire, Peter. Law and War: International Law and American History. Columbia University Press (2010), 108

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist Penal System. McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 0786403365.

- ^ Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist Penal System. McFarland. p. 148. ISBN 0786403365. Pohl cites Russian archival sources for the death toll in the special settlements from 1941-49

- ^ "UNPO: Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". unpo.org.

- ^ Naimark, Norman M (2011). Stalin's Genocides. Human Rights and Crimes Against Humanity. Princeton University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0691147840. OCLC 587249108.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0415777575.

- ^ "Ukraine's Parliament Recognizes 1944 'Genocide' Of Crimean Tatars". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 12 November 2015.

- ^ For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing," see:

- Pappé 2006.

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107[permanent dead link]: "The expulsion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- ^ "Israel Bars Rabin from Relating '48 Eviction of Arabs". The New York Times. 23 October 1979.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Benny, Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521009676.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Shipler1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh (2001). The Oxford companion to military history (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0198662099.

On 12 July, the Arab inhabitants of the Lydda-Ramle area, amounting to some 70,000, were expelled in what became known as the 'Lydda Death March'.

- ^ Chamberlin, P.T. (2012). The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order. Oxford Studies in International History. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-997711-6. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

On a visit home in 1948, Habash was caught in the Jewish attack on Lydda and, along with his family, forced to leave the city in the mass expulsion that came to be known as the Lydda Death March.

- ^ Palumbo, Michael (1987). The Palestinian Catastrophe. Quartet Books. pp. 184–189. ISBN 0-7043-0099-0.

- ^ Saleh Abdel Jawad, 2007, Zionist Massacres: the Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem in the 1948 War

- ^ Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, vol.3, Fayard 2007 p. 145 states that Aref al-Aref set the figure at 500, among an estimated 1300 who died either in fighting in Lydda or on the march that ensued."Le nombre total de morts se monte à 1,300 : 800 lors des combats de la ville, le reste dans l'exode."

- ^ Walid Khalidi in Munayyer, Spiro. “The Fall of Lydda.” Journal of Palestine Studies 27, no. 4 (1998): 80–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2538132. "The Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref; who interviewed survivors at the time, estimates that 350 died of thirst and exhaustion in the blazing July sun, when the temperature was one hundred degrees in the shade."

- ^ Nur Masalha 2003, p. 47 writes that 350 died.

- ^ For the number of refugees who died during the march:

- Morris 1989, pp. 204–211: "Quite a few refugees died – from exhaustion, dehydration and disease."

- Morris 2003, p. 177: "a handful, and perhaps dozens, died of dehydration and exhaustion."

- Morris 2004, p. 433: "Quite a few refugees died on the road east," attributing a figure of 335 dead to Muhammad Nimr al Khatib, who Morris writes was working from hearsay.

- ^ Morris 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Morris2004p433was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morris 1986

- ^ Michael Palumbo, The Palestinian Catastrophe: The 1948 Expulsion of a People from Their Homeland (London: Quartet Books, 1989). Pp. 233. (First published by Faber and Faber, 1987).

- ^ Terence Roehrig (2001). Prosecution of Former Military Leaders in Newly Democratic Nations: The Cases of Argentina, Greece, and South Korea. McFarland & Company. p. 139. ISBN 978-0786410910.

- ^ Lewis H. Carlson (2002). Remembered Prisoners of a Forgotten War: An Oral History of Korean War POWs. St Martin's Press. pp. 49–50, 60–62. ISBN 0312286848.