James V

| James V | |

|---|---|

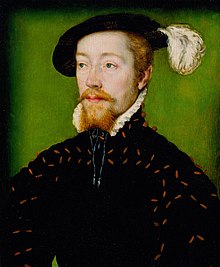

Portrait by Corneille de Lyon, c. 1536 | |

| King of Scotland | |

| Reign | 9 September 1513 – 14 December 1542 |

| Coronation | 21 September 1513 |

| Predecessor | James IV |

| Successor | Mary |

| Regents | See list

|

| Born | 10 April 1512 Linlithgow Palace, Linlithgow, Scotland |

| Died | 14 December 1542 (aged 30) Falkland Palace, Fife, Scotland |

| Burial | 8 January 1543 |

| Spouses | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Stewart |

| Father | James IV of Scotland |

| Mother | Margaret Tudor |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England. During his childhood Scotland was governed by regents, firstly by his mother until she remarried, and then by his first cousin once removed, John Stewart, Duke of Albany. James's personal rule began in 1528 when he finally escaped the custody of his stepfather, Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus. His first action was to exile Angus and confiscate the lands of the Douglases.

James greatly increased his income by tightening control over royal estates and from the profits of justice, customs and feudal rights. He founded the College of Justice in 1532 and also acted to end lawlessness and rebellion in the Borders and the Hebrides. The rivalry among France, England and the Holy Roman Empire lent James unwonted diplomatic weight, and saw him secure two politically and financially advantageous French marriages, first to Madeleine of Valois and then to Mary of Guise. James also fathered at least nine illegitimate children by a series of mistresses.

James's reign witnessed the beginnings of Protestantism in Scotland, and his uncle Henry VIII of England's break with Rome in the 1530s placed James in a powerful bargaining position with the papacy, allowing James to exploit the situation to increase his control over ecclesiastical appointments and the financial dividends from church revenues. Pope Paul III also granted him the title of Defender of the Faith in 1537. James maintained diplomatic correspondence with various Irish nobles and chiefs throughout their resistance to Henry VIII in the 1530s, and in 1540 they offered him the kingship of Ireland. A patron of the arts, James spent lavishly on the construction of several royal residences in the High Gothic and Renaissance styles.

James has been described as a vindictive king, whose policies were largely motivated by the pursuit of wealth, and a paranoid fear of his nobility which led to the ruthless appropriation of their lands. He has also been characterised as the "poor man's king", due to his accessibility to the poor and his acting against their oppressors. James died in December 1542 following the Scottish defeat by the English at the Battle of Solway Moss. His only surviving legitimate child, Mary, succeeded him at the age of just six days old.

Early life

James was the third son of King James IV and his wife Margaret Tudor, the eldest daughter of Henry VII of England, and was the only legitimate child of James IV to survive infancy. He was born on 10 April 1512 at Linlithgow Palace and baptised the following day,[1] receiving the title Duke of Rothesay.[2] James became king at just seventeen months old when his father was killed at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.

James was crowned in the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle on 21 September 1513. The nobility accepted Margaret Tudor as regent for her young son, in accordance with the terms of James IV's will, which also stated that Margaret was to retain this position so long as she remained a widow.[3] The long minority of James V would last for nearly fifteen years, with Margaret's position as regent soon challenged by the French-born John, Duke of Albany, who was James V's second cousin and the nearest male heir to the throne after the king and his younger brother, Alexander, Duke of Ross, who was born in April 1514.[4]

In August 1514, Margaret married Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus. This marriage was opposed by many among the nobility, who feared the advancement of the Douglases, and sought to deprive Margaret of the regency because she had remarried.[5]

The Privy Council removed Margaret from the office of regent and appointed the Duke of Albany to replace her.[5]

Minority rule

Albany's regency

Albany arrived at Dumbarton Castle with eight ships and a troop of French soldiers in May 1514.[6] He entered Edinburgh on 26 May, and in July Parliament confirmed his restoration as Duke of Albany and his position as regent. Albany's noble supporters intended his arrival to bring stable and good government, while Francis I of France sought to use Albany to maintain support for the Auld Alliance with France.[7] The first year of his regency was a period when a vigorous defence of his authority was essential to prevent the crumbling of Scottish government either into anarchy or into English control.[7]

The struggle for control of the person of the King was an essential prelude to Albany's attempt to govern, as he was aware from the beginning that his claims to act for the King and with full royal authority depended on the continued goodwill of the King himself, or rather of whoever had control of his person and could therefore claim to speak with his voice. Margaret and Angus were potentially hostile to Albany's intentions, and James V had to be removed from their influence.[8] Albany besieged Stirling Castle and Margaret was forced to relinquish possession of the King and the Duke of Ross.[7] James would not see his mother again for two years.[9] Having lost the regency, her income and control of her sons, Margaret departed from the court in September 1515, fleeing from Linlithgow Palace, where she had gone for her lying in, to Tantallon Castle, where she gave birth to her daughter, Lady Margaret Douglas, in Northumberland.[10]

The birth and long journey left her extremely ill and she was not told of the death of her second son Alexander in December 1515 until she had recovered her strength. The Earl of Angus made his peace with Albany later in 1516.[11]

A contemporary tribute, paid to the Duke of Albany's success in bringing order and good government to Scotland, by Sebastian Giustinian, the Venetian Ambassador at Henry VIII's Court, was that Scotland, "...was as much under Albany's control as if he were King...".[12] In February 1517, James was brought from Stirling to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, but during an outbreak of plague in the city, he was moved to the care of Antoine d'Arces at nearby rural Craigmillar Castle.[13]

At Stirling, the ten-year-old James had a guard of 20 footmen dressed in his colours, red and yellow. When he went to the park below the Castle, "by secret and in right fair and soft wedder (weather)", six horsemen would scour the countryside two miles roundabout for intruders.[14] Poets wrote their own nursery rhymes for James and advised him on royal behavior. Although his academic development was effectively cut short under Angus's captivity from 1525 onward, James V had been given a strong grounding by a number of tutors, including David Lyndsay and Gavin Dunbar.[15] James had been taught French and Latin, but as an adult, he spoke halting French, and his need for an interpreter to converse with an Italian bishop suggests that his spoken Latin and Italian were poor.[15][16]

Between 1517 and 1520, Albany sojourned in France, and did not exercise the regency in person, but through his lieutenants including Antoine d'Arces, sieur de la Bastie. On 26 August 1517 Albany and Charles, Duke of Alençon agreed the Treaty of Rouen, which renewed the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France and promised a French royal bride for James V. At England's request, Albany was detained in France for four years, and with him absent, Queen Margaret returned to Scotland and sought in vain to regain the regency.[9] Young James V was kept a virtual prisoner by Albany and his lieutenants, and Margaret was allowed to see her son only once between 1516 and the end of Albany's regency in 1524. Following the signing of the Treaty of Bruges (1521) between Henry VIII of England and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Francis I allowed the Duke of Albany to return to Scotland to strengthen the Franco-Scottish alliance.[17]

The Treaty of Rouen was ratified, and Madeleine of Valois was suggested as a suitable bride for James V. When the Duke of Albany returned in November 1521 Margaret sided with him against her husband, the Earl of Angus. Albany came to Edinburgh Castle, where James V was kept, and in a public ceremony, the keeper gave him the keys, which he passed to Margaret, who gave them back to Albany, symbolising that the government of Scotland was in his hands.[18] Thus, Albany was able to keep an upper hand in regard to the ambitious Angus. The regent put Angus under charges of high treason in December 1521 and later sent him practically a prisoner to France. In November 1522, Albany took an army to besiege Wark Castle defended by William Lisle, but gave up after three days when the weather deteriorated.[19]

Margaret's coup

In 1524, Albany was finally removed from power in a coup d'état while he was in France. Margaret, with the help of James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran and his followers, brought James V from Stirling to Edinburgh.[17] In August, Parliament declared the regency at an end, and the 12-year-old King James was prematurely "erected" to full kingly powers. In November, Parliament formally recognised Margaret as the chief councillor to the King.[17] Margaret's alliance with the Hamiltons inevitably alienated other noble houses. Henry VIII allowed the Earl of Angus (who Albany had banished) to return to Scotland in 1524, and he entered into an alliance with John Stewart, 3rd Earl of Lennox, an enemy of Margaret and Arran.[17] When Angus arrived in Edinburgh with a large group of armed men, claiming his right to attend Parliament, Margaret ordered cannons to be fired on them from Edinburgh Castle.[17] Parliament subsequently made Angus a Lord of the Articles and a member of the council of regency.

Angus captivity

A plan was agreed to end the feuding among these opposing groups by allowing each of them in turn to act as host to the young king. However, the plan fell apart in November 1525 when, at the end of his period of custody, Angus refused to surrender the King who, in effect, became a prisoner of the Red Douglases for the next two-and-a-half years.[17] Angus again "erected" James V to full kingly powers, took him on justice ayres and kept him under close supervision. He spoiled the King with various lavish gifts in an attempt to buy his favour and make the detention more tolerable, and when James showed signs of tiring of these gifts, Angus also introduced the adolescent king to the pleasures of the flesh with a succession of prostitutes.[20]

Angus overreached himself, assuming the office of Lord Chancellor, and granting his followers almost every lucrative post available in the royal household.[20] While James V clearly enjoyed some aspects of his captivity, he grew to hate his captor. Several attempts were made to free the young king—one by Walter Scott of Branxholme and Buccleuch, who ambushed the King's forces on 25 July 1526 at the Battle of Melrose and was routed off the field. Another attempt later that year, on 4 September at the Battle of Linlithgow Bridge, failed again to relieve the King from the clutches of Angus.[20] In May 1528 James finally escaped from Angus's captivity when he fled from Edinburgh to Stirling in disguise. After meeting with his mother at Stirling, James V re-entered Edinburgh in July with a large army. Summoned for treason, Angus holed himself up in Tantallon Castle until an agreement was reached whereby he was allowed to go into exile in England after surrendering his castles.[20]

Personal rule

Pierre de Ronsard saw James in 1537 when the King was twenty-four and summed up his paradoxical appearance: "La douceur et la force illustroient son visage Si que Venus et Mars en avoient fait partage" – His royal bearing, and vigorous pursuit of virtue, of honour, and love's war, this sweetness and strength illuminate his face, as if he were the child of Venus and Mars.[15]

Religion

The first action James took as king was to remove Angus from the scene. The Douglas family — excluding James's half-sister Margaret, who was already safely in England, innocent of any crime against him (and thus safe from any revenge James took) — were forced into exile and James besieged their castle at Tantallon. He then subdued the Border rebels and the chiefs of the Western Isles. As well as taking advice from his nobility and using the services of the Duke of Albany in France and at Rome, James had a team of professional lawyers and diplomats, including Adam Otterburn and Thomas Erskine of Haltoun. Even his pursemaster and yeoman of the wardrobe, John Tennent of Listonschiels, was sent on an errand to England, though he got a frosty reception.[21]

James increased his income by tightening control over royal estates and from the profits of justice, customs and feudal rights. He also gave his illegitimate sons lucrative benefices, diverting substantial church wealth into his coffers. James spent a large amount of his wealth on building up a collection of tapestries from those inherited from his father.[22] James sailed to France for his first marriage and strengthened the royal fleet. In 1540, he sailed to Kirkwall in Orkney, then Lewis, in his ship the Salamander, first making a will in Leith, knowing this to be "uncertane aventuris." The purpose of this voyage was to show the royal presence and hold regional courts, called "justice ayres."[23]

Domestic and international policy was affected by the Reformation, especially after Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church. James V did not tolerate heresy and during his reign a number of outspoken Protestants were persecuted. The most famous of these was Patrick Hamilton, who was burned at the stake as a heretic at St Andrews in 1528. Later in the reign, the English ambassador Ralph Sadler tried to encourage James to close the monasteries and take their revenue so that he would not have to keep sheep like a mean subject. James replied that he had no sheep, he could depend on his god-father the king of France, and it was against reason to close the abbeys that "stand these many years, and God's service maintained and kept in the same, and I might have anything I require of them."[24] Sadler knew that James did farm sheep on his estates.[25]

James recovered money from the church by getting Pope Clement VII to allow him to tax monastic incomes.[26] He sent £50 to Johann Cochlaeus, a German opponent of Martin Luther, after receiving one of his books in 1534.[27] On 19 January 1537, Pope Paul III sent James a blessed sword and hat symbolising his prayers that James would be strengthened against heresies from across the border.[28] These gifts were delivered by the Pope's messenger while James was at Compiègne in France on 25 February 1537.[29]

According to 16th-century writers, his treasurer James Kirkcaldy of Grange tried to persuade James against the persecution of Protestants and to meet Henry VIII at York.[30] James and Henry corresponded about meeting in 1536. Pope Paul III advised James against travelling to England, and sent an envoy or nuncio to Scotland to discuss the initiative.[31] Although Henry VIII sent his tapestries to York in September 1541 ahead of a meeting, James did not come. The lack of commitment to this meeting was regarded by English observers as a sign that Scotland was firmly allied to France and Catholicism, particularly by the influence of Cardinal Beaton, Keeper of the Privy Seal, and as a cause for war.[32]

In 1540, Irish nobles and chiefs offered James the kingship of Ireland, as a further challenge to Henry VIII.[33]

Building

James V spent a large amount of money (at least £41,000) during his adult reign on extensively remodelling all the major residences and several minor ones, including the construction of new structures, with the most significant work focused on Falkland Palace and Stirling Castle.[34][35] Early in his personal rule James began the construction of the present Late Gothic James V Tower at the north-west corner of the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which provided new royal lodgings on the first and second floors, and a high degree of security. A new west front was also built.[36][37] At Linlithgow Palace, James closed off the original east entranceway and formed a new formal access from the south, including an inner gatehouse and an outer entrance gate decorated with the carved arms of the four chivalric orders of which James was a member: Garter, Thistle, Golden Fleece and Saint Michael. The three-tiered octagonal King's Fountain topped by an imperial crown was built in 1538 as the centrepiece of the courtyard.[38]

At Falkland Palace, James V extended his father's buildings in French Renaissance style between 1537 and 1541 and built a real tennis court in the garden in 1541.[39] The court survives to this day and is the oldest in the United Kingdom. James also built a new Late Gothic entrance tower in the south range, and the courtyard facades of the east and south ranges that were built in 1537 and 1539 are the earliest examples of Renaissance architecture in the British Isles.[34][40] The largest of James V's building projects was the construction of the Royal Palace at Stirling Castle, built between 1538 and 1540, with its Renaissance facades and the north, east and south quarters housing the king's and queen's apartments. Work was also carried out at Tantallon Castle, Blackness Castle and Hermitage Castle.[41]

Marriages

As early as August 1517, a clause of the Treaty of Rouen provided that if the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland was maintained, James should have a daughter of Francis I of France as a bride. Yet by the 1520s Francis's two surviving daughters were too frail or too young.[42] In 1528 the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the English diplomat Thomas Magnus both raised the possibility of a marriage between the King and his cousin, Princess Mary, while that same year, Margaret of Austria, Charles V's aunt, suggested that James should marry Charles's sister, Mary of Austria.[43] Charles V also proposed James marry his niece, Maria of Portugal. Perhaps to remind Francis I of his obligations, in 1529 James V began negotiations for his marriage elsewhere, sending the Duke of Albany to Rome to negotiate a marriage to Catherine de' Medici, the niece of Pope Clement VII.[44] By 1533 there was discussion of James marrying one of his second cousins, Christina or Dorothea, the daughters of Christian II of Denmark, while in 1534 Margaret of Valois-Angoulême, sister of Francis I, suggested her sister-in-law Isabella.[45]

In December 1534, Francis I insisted that his eldest daughter Madeleine's health was too poor for marriage, suggesting that James V should marry Mary of Bourbon, daughter of the Duke of Vendôme, instead to fulfil the Treaty of Rouen. Again, the Duke of Albany briefly entertained the idea that James might marry Christina of Denmark, and the King halted progress on the marriage negotiations. There was also an investigation into the possibility of James marrying his former mistress, Margaret Erskine before the negotiations resumed again, and in March 1536 a final contract made for Mary of Bourbon to marry James V. She would have a dowry as if she were a French princess, and Francis I consolidated the agreement by sending James the collar of the Order of Saint Michael as a token of his affection.[46]

Marriage to Madeleine of Valois

James decided to travel to France to meet his prospective bride in person. He sailed from Kirkcaldy on 1 September 1536, with the earls of Arran, Argyll and Rothes, Lord Fleming, David Beaton and a force of 500 men in a fleet of six ships, using the Mary Willoughby as his flagship.[47] Before his departure, James appointed six vice-regents to govern Scotland in his absence.[48] In the event, James V would be away from Scotland for eight months, becoming the first Scottish king to voluntarily remain away from his realm since David II almost two hundred years earlier.[49] Arriving at Dieppe a week later, the Scots travelled to the Duke of Vendôme's court at Saint-Quentin. However, on meeting Mary of Bourbon, James V was not impressed by her. He then travelled south to the French court at the Château d'Amboise, where he met Madeleine, and again pressed Francis for her hand in marriage. Fearing the harsh climate of Scotland would prove fatal to his daughter's already failing health, Francis initially refused to permit the marriage, but the couple persuaded Francis to reluctantly grant permission to their marriage.[50] The marriage contract was signed in November, with Francis I granting Madeleine a dowry of 100,000 écu, and a further 30,000 francs a year for James.[51]

James V renewed the Auld Alliance and fulfilled the terms of the Treaty of Rouen on 1 January 1537 by marrying Madeleine at Notre-Dame de Paris. James received papal approval in the form of the Blessed sword and hat, and was granted the title of Defender of the Faith by Pope Paul III on 19 January 1537, symbolising the hopes of the papacy that he would resist the path that his uncle Henry VIII had followed.[52][53] After months of festivities and celebrations, and visits to Chantilly, Compiègne and Rouen (where Madeleine fell ill), the royal couple embarked for Scotland in May 1537, arriving at Leith on 19 May.[54] Madeleine wrote to her father from Edinburgh on 8 June 1537 saying that she was better and her symptoms had diminished.[55] However, a month later, on 7 July 1537, Queen Madeleine died in her husband's arms at Holyrood Palace of tuberculosis.[56] James V wrote to Francis I to inform him of what had happened, saying that if it were not for the fact that he was relying on the French king to remain his "good father", he would be in even greater pain.[56] The Queen was interred in Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh.

Marriage to Mary of Guise

Following Madeleine's death, James V's thoughts turned to a second French bride to further the interests of the Franco-Scottish alliance. David Beaton was sent to France to persuade Francis I to agree to James marrying his only surviving daughter, Margaret.[56] Francis offered Mary of Guise as a bride instead. The daughter of Claude, Duke of Guise, Mary had recently been widowed by the death of her husband, Louis II d'Orléans, Duke of Longueville. David Beaton wrote to James V from Lyon in October 1537 that Mary was "stark (strong), well complexioned, and fit to travel", and that her father was "marvellous desirous of the expedition and hasty end of the matter," and had already consulted with his brother, Antoine, Duke of Lorraine, and Mary herself.[57] The marriage contract was finalised in January 1538, with James V receiving a dowry of 150,000 livres. As was customary, if the King died first, Mary would retain for her lifetime her jointure houses of Falkland Palace, Stirling Castle, Dingwall Castle and Threave Castle, along with the rentals of the earldoms of Fife, Strathearn, Ross and Orkney, and the lordships of Galloway, Ardmannoch and the Isles.[58]

The proxy wedding of James V and Mary of Guise was held on 9 May 1538 at the Château de Châteaudun. Some 2,000 Scottish lords and barons came from Scotland aboard a fleet of ships under Lord Maxwell to attend, with Lord Maxwell standing as proxy for James V. Mary departed from Le Havre on 10 June 1538, and landed in Scotland 6 days later at Crail in Fife. She was formally received by the king at St Andrews a few days later amid pageants and plays performed in her honour, and James and Mary were married in person at St Andrews Cathedral on 18 June 1538. James's mother Margaret Tudor wrote to Henry VIII in July, "I trust she will prove a wise Princess. I have been much in her company, and she bears herself very honourably to me, with very good entertaining."[59] James and Mary had two sons: James, Duke of Rothesay (born 22 May 1540 at St Andrews), and Robert (or Arthur), Duke of Albany (born and baptised on 12 April 1541); however, both died on 21 April 1541, when James was nearly one year old and Robert (or Arthur) was nine days old. Mary's mother, Antoinette de Bourbon, wrote that the couple were still young and should hope for more children.[60] The third and last child of the union was a daughter, Mary, who was born on 8 December 1542.[61]

Outside interests

According to legend, James was nicknamed "King of the Commons" as he would sometimes travel around Scotland disguised as a common man, describing himself as the "Gudeman of Ballengeich".[62] ("Gudeman" means "landlord" or "farmer", and "Ballengeich" was the nickname of a road next to Stirling Castle — meaning "windy pass" in Gaelic[63]). One traditional ballad, The Jolly Beggar, is considered by some to refer to his activities.[64]

James was also a keen lute player.[65] In 1562, Sir Thomas Wood reported that James had "a singular good ear and could sing that he had never seen before" (sight-read), but his voice was "rawky" and "harske." At court, James maintained a band of Italian musicians who adopted the name Drummond. These were joined for the winter of 1529/30 by a musician and diplomat sent by the Duke of Milan, Thomas de Averencia de Brescia, probably a lutenist.[66] The historian Andrea Thomas makes a useful distinction between the loud music provided at ceremonies and processionals and instruments employed for more private occasions or worship, the music fyne described by Helena Mennie Shire. This quieter music included a consort of viols played by four Frenchmen led by Jacques Columbell.[67] It seems certain that David Peebles wrote music for James V and probable that the Scottish composer Robert Carver was in royal employ, though evidence is lacking.[68]

As a patron of poets and authors, James supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, the son of his nurse, who translated the Latin History of Scotland compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece into verse and prose.[69] Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, the Lord Lyon, head of the Lyon Court and diplomat, was a prolific poet. He produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace thought to be a version of his play The Thrie Estaitis in 1540. James also attracted the attention of international authors. The French poet Pierre de Ronsard, who had been a page of Madeleine of Valois, offered unqualified praise:

"Son port estoit royal, son regard vigoureux

De vertus, et de l'honneur, et guerre amoureux

La douceur et la force illustroient son visage

Si que Venus et Mars en avoient fait partage"

His royal bearing, and vigorous pursuit

of virtue, of honour, and love's war,

this sweetness and strength illuminate his face,

When he married Mary of Guise, Giovanni Ferrerio, an Italian scholar who had been at Kinloss Abbey in Scotland, dedicated to the couple a new edition of his work On the True Significance of Comets against the Vanity of Astrologers.[72] Like Henry VIII, James employed many foreign artisans and craftsmen in order to enhance the prestige of his renaissance court.[73] Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie listed their professions:

he plenished the country with all kind of craftsmen out of other countries, as French-men, Spaniards, Dutch men, and Englishmen, which were all cunning craftsmen, every man for his own hand. Some were gunners, wrights, carvers, painters, masons, smiths, harness-makers (armourers), tapesters, broudsters, taylors, cunning chirugeons, apothecaries, with all other kind of craftsmen to apparel his palaces.[74]

One technological initiative was a special mill for polishing armour at Holyroodhouse next to his mint. The mill had a pole drive 32 feet long powered by horses.[75] Mary of Guise's mother Antoinette of Bourbon sent him an armourer. The armourer made steel plates for his jousting saddles in October 1538 and delivered a skirt of plate armour in February 1540. In the same year, for his wife's coronation, the treasurer's accounts record that James personally devised fireworks made by his master gunners. His goldsmith John Mosman renovated the crown jewels for the occasion.[76] When James took steps to suppress the circulation of slanderous ballads and rhymes against Henry VIII, Henry sent Fulke ap Powell, Lancaster Herald, to give thanks and to make arrangements for the present of a lion for James's menagerie of exotic pets.[77]

War with England and death

The death of James's mother in 1541 removed any incentive for peace with England, and war broke out. Initially, the Scots won a victory at the Battle of Haddon Rig in August 1542. The Imperial ambassador in London, Eustace Chapuys, wrote on 2 October that the Scottish ambassadors ruled out a conciliatory meeting between James and Henry VIII in England until the pregnant Mary of Guise delivered her child. Henry would not accept this condition and mobilised his army against Scotland.[78] James was with his army at Lauder on 31 October 1542. Although he hoped to invade England, his nobles were reluctant.[79] He returned to Edinburgh, on the way writing a letter in French to his wife from Falahill mentioning he had three days of illness.[80] On 24 November his army suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss. Following a few days spent at Linlithgow Palace with Queen Mary, who was in the final stages of her pregnancy, on 6 December James travelled to Falkland Palace, where he soon took ill.[81][16]

Although James V's army had been beaten at Solway Moss, it was neither a personal humiliation for the King (who was not there) nor the result of noble disaffection. In fact, James had substantial support for his war policy and early in December, he had made plans to renew the conflict with England.[16] James was on his deathbed at Falkland when news arrived from Linlithgow that the Queen had given birth to a daughter. According to John Knox, on hearing of the birth of his daughter, the King said "It cam wi' a lass, and it will gang wi' a lass" (meaning "It began with a girl and it will end with a girl").[82] This could refer to the Stewart dynasty's accession to the throne through Marjorie Bruce, daughter of Robert the Bruce. The prophecy could have been intended to express his belief that his new-born daughter Mary would be the last of the Stewart monarchs. In fact, the last Stewart monarch was female: Anne, Queen of Great Britain. James V died at Falkland Palace on 14 December 1542, aged thirty. The King had been ill on a number of occasions during the previous decade: in 1533 "of a sore fois (face)"; in 1534 of the "pox, and fevir contenew"; in Paris in 1536; and in 1540, when he wrote to his wife to say that he had been as ill as he had ever been in his life, but was now recovered. Evidently, his immune system had not recovered, as he had been ill again in November 1542.[16] It is likely that James V died from cholera or dysentery, rather than shame or despair brought on by the news of Solway Moss.[16]

James was succeeded by his infant daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots. On 7 January 1543, the King's body was conveyed from Falkland to the Forth ferry at Kinghorn, before being transported to Edinburgh, escorted by a funeral cortege, and accompanied by Cardinal Beaton, the Earls of Arran, Argyll, Rothes, Marischal and other nobles.[73] James V was buried on 8 January at Holyrood Abbey, next to his first wife, Madeleine, and his two sons. A stone tomb was erected, on which Andrew Mansioun carved a lion, a crown and an eighteen-foot-long inscription in Roman letters. Alms were distributed to the poor of Edinburgh who had been present at the soul-Mass and dirge performed for the King.[73] During the Rough Wooing, the invading English armies inflicted structural damage on Holyrood Abbey in 1544 and 1547, destroying James V's tomb.[83][84]

James was the last monarch to die in Scotland until 8 September 2022 when Queen Elizabeth II died at Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire, 480 years later. Days later her body was carried through the streets of Edinburgh, the first time that a royal cortege had passed through the city since James V's burial.[85]

Issue

Legitimate issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Madeleine of France | |||

| no issue | |||

| By Mary of Guise | |||

| James, Duke of Rothesay | 22 May 1540 | 21 April 1541 | |

| Arthur or Robert, Duke of Albany | 12 April 1541 | 20 April 1541 | |

| Mary, Queen of Scots | 8 December 1542 | 8 February 1587 | Married, firstly, Francis II of France; no issue. Married, secondly, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, and had issue (the future James VI and I). Married, thirdly, James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell; no issue. |

Illegitimate issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Elizabeth Shaw | |||

| James Stewart, Commendator of Kelso and Melrose | c. 1529[86] | 1557 | His daughter, Marjorie, married the half-nephew of his brother, Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney. Some sources, however, state he had no issue. |

| By Margaret Erskine | |||

| James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray | c. 1531[86] | 23 January 1570 | Prior of St Andrews; Regent of Scotland, for his nephew James VI and I. Married Agnes Keith, Countess of Moray, and had issue. He was the first head of government to be assassinated with a firearm. |

| Robert Stewart | ? | 1581[87] | Prior of Whithorn |

| By Elizabeth Stewart | |||

| Adam Stewart, Prior of Perth | ? | 20 June 1575 | Married Janet Ruthven and had issue. In June 1596, James VI gave £200 to Adam's son, James Stewart, for his travelling expenses in foreign countries.[88] |

| By Christine Barclay | |||

| James Stewart | ? | ? | |

| By Elizabeth Carmichael | |||

| John Stewart, Commendator of Coldingham | c. 1531[86] | November 1563 | Married Jean Hepburn and had issue including Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell. Also had illegitimate issue. |

| By Elizabeth Bethune | |||

| Lady Jean Stewart | c. 1533 | 7 January 1587/88 | Married Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll; no issue. |

| By Euphame Elphinstone | |||

| Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney and Lord of Zetland (Commendator of Holyrood) | c. 1533[86] | 4 February 1593 | Married Jean Kennedy and had issue. Also had illegitimate issue. |

| Unnamed child | ? | ? | Died in childhood |

Fictional portrayals

James V has been depicted in historical novels, poems, short stories and one notable opera. They include the following:[89]

- Scott, Walter (1810), The Lady of the Lake, a Romantic narrative poem set in the Trossachs. He appears in disguise. The poem was tremendously influential in the nineteenth century and inspired the Highland Revival. James also features in Scott's Tales of a Grandfather.

- "Johnnie Armstrong", a traditional ballad relating the story of Scottish raider and folk hero Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie, who was captured and hanged by King James V in 1530.

- Rossini, Gioachino (1819), La Donna del Lago, an opera based on Scott's poem. Sung in Italian, James V appears as "Giacomo V".

- Gibbon, Charles (1881), The Braes of Yarrow. The novels features Scotland in the aftermath of the Battle of Flodden, covering events to 1514. Margaret Tudor, "Boy-King" James V and Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Angus, are prominently featured.[90]

- Barr, Robert (1902), A Prince of Good Fellows. James is the titular prince and the main character. He is depicted as an "adventure-loving persona".[89]

- Gunn, John (1913), The Fight at Summerdale. The novel depicts Orkney, Edinburgh and Normandy in the 16th century. James V "appears more than once" in the various chapters.[89]

- Knipe, John (1921), The Hour Before the Dawn. Depicts events "just before" and "after" the death of James V. James V, Mary of Guise and David Beaton are prominently depicted.[89]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of James V | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ Robert Kerr Hannay, Letters of James IV (SHS: Edinburgh, 1953), p. 243.

- ^ Mackay, Æneas (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 29. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 153–161.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 3.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. xii.

- ^ a b Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 28.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 54.

- ^ a b c Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 60.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 79.

- ^ a b Ross, Stewart, The Stewart Dynasty (Thomas and Lochar, 1993), p. 194.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 61.

- ^ Emond, Ken, James V (John Donald, 2019), p. 143.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 5, p. 130.

- ^ HMC Earl of Mar & Kellie at Alloa House (London, 1904), pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c Ross, Stewart, The Stewart Dynasty (Thomas and Lochar, 1993), p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell, 1998), p. 556.

- ^ a b c d e f Ross, Stewart, The Stewart Dynasty (Thomas and Lochar, 1993), p. 195.

- ^ Ken Emond, The Minority of James V (Edinburgh, 2019), p. 140.

- ^ Ken Emond, The Minority of James V (Edinburgh, 2019), p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Ross, Stewart, The Stewart Dynasty (Thomas and Lochar, 1993), p. 196.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), 12–15, 36: Murray, Atholl, 'Pursemaster's Accounts', Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, vol. 10 (SHS: Edinburgh, 1965), pp. 13–51.

- ^ Dunbar, John G., Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1999).

- ^ HMC Mar & Kellie (London, 1904), 15, Will 12 June 1540: Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1998), pp. 245–248.

- ^ Clifford, Arthur ed., Sadler State Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1809), p. 30.

- ^ Athol Murray, 'Crown Lands', An Historical Atlas of Scotland (Scottish Medievalists, 1975), p. 73: After James's death, 600 sheep were given to James Douglas of Drumlanrig, HMC 15th Report: Duke of Buccleuch (London, 1897), p. 17.

- ^ Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell, 1998), p. 260.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 236.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., Letters of James V ( (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1954), 328:Reid, John J., 'The Scottish Regalia', PSAS, 9 December (1889) Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 28: this sword is lost.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 18.

- ^ Steuart, A. Francis, ed., Memoirs of Sir James Melville of Halhill (Routledge, 1929), pp. 14–17.

- ^ Denys Hay, Letters of James V (Edinburgh, 1954), p. 320.

- ^ Campbell, Thomas P., Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Tapestries at the Tudor Court (Yale, 2007), p. 261.

- ^ Thomas D'Arcy McGee (1862), A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics, Book VII, Chapter III.

- ^ a b Dunbar, John G., Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1999), p. 27.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), p. 92.

- ^ Dunbar, John G., Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1999), p. 61.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Dunbar, John G., Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1999), p. 18.

- ^ Henry Paton, Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 270, 275, 279–281.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), p. 111.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), p. 49.

- ^ Hay, Denys, Letters of James V (HMSO, 1954), pp. 51–52.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part IV (London, 1836), p. 545.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., The Letters of James V, HMSO (1954), pp. 173, 180–182, 189,

- ^ Calendar of State Papers Venice, vol. 4 (London, 1871), no. 861.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., The Letters of James V (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1954), 318: Bapst, E., Les Mariages de Jacques V, 273.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont. (London, 1836), pp. 59–60.

- ^ The vice-regents were Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow (the Lord Chancellor), James Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews, the earls of Huntly, Montrose, and Eglinton, and Lord Maxwell (Cameron 1998, p. 288).

- ^ Cameron, Jamie, James V, Tuckwell (1998), p. 133.

- ^ Rosalind K. Marshall, Scottish Queens, 1034–1714 (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 102–103.

- ^ Rosalind K. Marshall, Scottish Queens, 1034–1714 (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2003), p. 104.

- ^ Jamie Cameron, James V (East Linton: Tuckwell, 1998), p. 288.

- ^ Denys Hay, Letters of James V, HMSO (1954), 328.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont., (1836), 79, Clifford to Henry VIII.

- ^ Denys Hay, Letters of James V (Edinburgh: HMSO, 1954), pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b c Marshall, Rosalind, Scottish Queens, 1034–1714 (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2003), p. 108.

- ^ Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 12, part 2 (London, 1891) no. 962: Lang, Andrew, 'Letters of Cardinal Beaton, SHR (1909), 156: Marshall (1977), 45, (which suggests he thought the couple had not met)

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., The Letters of James V (HMSO, 1954), pp. 340–341.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 (London, 1836), 135, Margaret to Henry, 31 July 1538.

- ^ Wood, Marguerite, Balcarres Papers, vol. 1 (STS, 1923), 60–61.

- ^ Fraser, Antonia, Mary Queen of Scots, pp. 3 & 12.

- ^ Bingham James V King of Scots

- ^ Black (1861), Picturesque Tourist of Scotland, pp. 180–181.

- ^ "The Gaberlunzie Man / The Beggar Man / The Auld Beggarman (Roud 212; Child 279 Appendix; Henry H810)".

- ^ "The Court of Mary, Queen of Scots", BBC Radio 3, 28 February 2010.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., Letters of James V (HMSO, 1954), pp. 63, 169, 170: Shire, Helena M., in Stewart Style (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1996), pp. 129–133.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 2005), pp. 92–94, 98: H. M. Shire, Song Dance and Poetry (Cambridge, 1969).

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 1998), pp. 105–107.

- ^ Van Heijnsbergen, Theo, 'Literature in Queen Mary's Edinburgh: the Bannatyne Manuscript', in The Renaissance in Scotland (Brill, 1994), pp. 191–196.

- ^ Bingham, Caroline, James V (Collins, 1971), p. 12, verse quoted from William Drummond of Hawthornden, History of the 5 Jameses (1655), pp. 348–349

- ^ Drummond of Hawthorden, William, Works, Edinburgh (1711), p. 115.

- ^ Ferrerio, Giovanni, De vera cometae significatione contra astrologorum omnium vanitatem. Libellus, nuper natus et aeditus, Paris, Vascovan, (1538).

- ^ a b c Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), pp. 226–243.

- ^ Lindsay of Pitscottie, Robert, The History of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1778), p. 238: abbreviated in Lindsay of Pitscottie, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1814), p. 359.

- ^ Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 101–102, 242 290: Thomas Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 2005), p. 173.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), 95, 287 (taslet), 357 fireworks: Marguerite Wood, Balcarres Papers, vol. 1 (SHS: Edinburgh, 1923), pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 14 part 1 (London, 1894), xix, no. 406: vol. 14 part 2 (London, 1895), no. 781.

- ^ Calendar State Papers Spanish: 1542–1543, vol. 6 part 2, London (1895), p. 144, no.66.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol.5 part 4 part 2, (1836), 213: Laing, David, ed., The Works of John Knox, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1846) pp. 389–391.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes, Lives of the queens of Scotland and English princesses, vol. 1, Blackwood (1850), 402 part translated only; now preserved as National Archives of Scotland SP13/27.

- ^ Knox, John, "from History of the Reformation, book 2". Archived from the original on 29 August 2009.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter, Tudors (The History of England Volume 2), Pan Books ISBN 978-1-4472-3681-8

- ^ Gallagher, p. 1085.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 8 (1908) 142–143: Works of Drummond of Hawthornden: History of the Five Jameses, (Edinburgh 1711), p. 116

- ^ Wade, Mike; Parker, Charlie (13 September 2022). "In hushed reverence, they lined Royal Mile". The Times. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d HMC: 6th Report & Appendix (London, 1877), p. 670: Pope Clement VII sent a dispensation to James V dated 30 August 1534 that allowed four of the children to take holy orders when they came of age. The document stated that James elder was in his fifth year, James younger and John in their third year, and Robert in his first year.

- ^ Gordon Donaldson, Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland: 1567-1574, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1963), p. 67 no. 298: Register of the Privy Seal, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1982), p. 485, no. 2742.

- ^ National Records of Scotland, Exchequer vouchers E23/7.

- ^ a b c d Nield (1968), p. 70

- ^ Nield (1968), p. 67

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "James V". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "James V". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- Bingham, Caroline (1971), James V King of Scots, London: Collins, ISBN 0-0021-1390-2

- Cameron, Jamie (1998), Macdougall, Norman (ed.), James V: The Personal Rule, 1528–1542, The Stewart Dynasty in Scotland, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 978-1-8623-2015-4

- Dawson, Jane (2007), Scotland Reformed 1488–1587, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, vol. 6, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1455-4

- Donaldson, Gordon (1965), Scotland: James V to James VII, The Edinburgh History of Scotland, vol. III, Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, ISBN 978-0-9018-2485-1

- Dunbar, John (1999). Scottish Royal Palaces. Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1--86232-042-X.

- Ellis, Henry, 'A Household book of James V', in Archaeologia, vol. 22, (1829), 1-12

- Emond, Ken (2019), The Minority of James V: Scotland in Europe, 1513–1528, Edinburgh: John Donald, ISBN 978-1-9109-0031-4

- Ross, Stewart (1993), The Stewart Dynasty, Nairn: Thomas and Lochar, ISBN 978-1-8998-6343-3

- Thomas, Andrea (2005), Princelie Majestie: The Court of James V of Scotland, Edinburgh: John Donald, ISBN 0--85976-611-X

- Hadley Williams, Janet (1996), Stewart Style 1513–1542, Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-8984-1082-8

- Hadley Williams, Janet (2000), Sir David Lyndsay, Selected Poems, Glasgow: ASLS, ISBN 0-9488-7746-4

- Harrison, John G. (2008). Wardrobe Inventories of James V: British Library MS Royal 18 C (PDF). Historic Scotland.

- Nield, Jonathan (1968), A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8337-2509-7

- Wormald, Jenny (1981), Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland 1470–1625, The New History of Scotland, vol. 4, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-0276-3

External links

Media related to James V of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James V of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons- James V at the official website of the British monarchy

- Portraits of James V at the National Portrait Gallery, London