Choquequirao

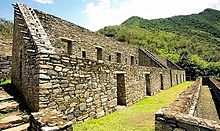

Choquequirao citadel. | |

| Location | Mollepata, Anta Province, Cusco Region, Peru |

|---|---|

| Region | Andes |

| Coordinates | 13°23′34″S 72°52′26″W / 13.39278°S 72.87389°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Founded | 1536 |

| Abandoned | 1572 |

| Cultures | Inca |

Choquequirao (possibly from Quechua chuqi metal, k'iraw crib, cot)[1][2][3][4] is an Incan site in southern Peru, similar in structure and architecture to Machu Picchu. The ruins are buildings and terraces at levels above and below Sunch'u Pata, the truncated hill top. The hilltop was anciently leveled and ringed with stones to create a 30 by 50 m platform.

Choquequirao at an elevation of 3,050 metres (10,010 ft) [5] is in the spurs of the Vilcabamba mountain range in the Mollepata district, Anta province of the Cusco Region. The complex is 1,800 hectares, of which 30–40% is excavated.[6] The site overlooks the Apurimac River canyon that has an elevation of 1,450 metres (4,760 ft).

The site is reached by a two-day hike from outside Cusco.[6] Choquequirao has topped in the prestigious Lonely Planet's Best in Travel 2017 Top Regions list.[7]

History

Choquequirao is a 15th- and 16th-century settlement associated with the Inca Empire, or more correctly Tahuantinsuyo.[8] The site had two major growth stages. This could be explained if Pachacuti founded Choquequirao and his son, Tupac Inca Yupanqui, remodeled and extended it after becoming the Sapa Inca.[9] Choquequirao is located in the area considered to be Pachacuti’s estate; which includes the areas around the rivers Amaybamba, Urubamba, Vilcabamba, Victos, and Apurímac.

Other sites in this area are Sayhuite, Machu Picchu, Chachabamba (Chachapampa), Choquesuysuy (Chuqisuyuy), and Guamanmarca (Wamanmarka); all of which share similar architectural styles with Choquequirao.[10] The architectural style of several important features appears to be of Chachapoya design, suggesting that Chachapoya workers were probably involved in the construction. This suggests that Tupaq Inka probably ordered the construction. Colonial documents also suggest that Tupac Inca ruled Choquequirao since his great grandson, Tupa Sayri, claimed ownership of the site and neighboring lands during Spanish colonization.[11]

It was one of the last bastions of resistance and refuge of the Son of the Sun (the "Inca"), Manco Inca Yupanqui, who fled Cusco after his siege of the city failed in 1535.

According to the Peruvian Tourism Office, "Choquequirao was probably one of the entrance check points to the Vilcabamba, and also an administrative hub serving political, social, and economic functions. Its urban design has followed the symbolic patterns of the imperial capital, with ritual places dedicated to Inti (the Incan sun god) and the ancestors, to the earth, water, and other divinities, with mansions for administrators and houses for artisans, warehouses, large dormitories or kallankas, and farming terraces belonging to the Inca or the local people. Spreading over 700 meters, the ceremonial area drops as much as 65 meters from the elevated areas to the main square."[5] The city also played an important role as a link between the Amazon Jungle and the city of Cusco.

Discovery

According to Ethan Todras-Whitehill of the New York Times, Choquequirao's first non-Incan visitor was the explorer Juan Arias Díaz in 1710.[12] The first written site reference in 1768 was made by Cosme Bueno, but was ignored at the time.

The Prefect of the Province of Apurimac, J.J. Nuñez, encouraged Hiram Bingham to visit the 'Cradle of Gold', in order to discover any Incan treasure. Bingham was a delegate to the 1908 First Pan American Scientific Congress and was in Cusco at the time. Bingham decided to visit Choquequirao in 1909 to determine if it was Vilcapampa, the Capital of the last four Incas. He found three groups of buildings, mummified bodies, and places where dynamite had been used in the search of treasure. Visitors who had recorded their names included Count de Sartiges, Jose Maria Tejada and Marcelino Leon, 1834, Jose Benigno Samanez, Juan Manuel Rivas Plata and Mariana Cisneros, 1861, and three Almanzas, Pio Mogrovejo, and their treasure hunting workmen, 1885. However, Bingham decided it was merely a frontier fortress, and it tempted him to search further.[13]

Location and layout

Choquequirao is situated at an elevation of 3,000 m above sea level on a southwest-facing spur of a glaciated peak above the Apurimac River.[14] The region is characterized by mountain topography and covered with Amazonian flora and fauna.[15] It is 98 km west of Cusco, in the Vilcabamba range. The complex covers 6 km2.[16] Architecturally it is similar to Machu Picchu. The main structures, such as temples, huacas, elite residences, and fountain/bath systems are concentrated around two plazas along the crest of the ridge, which encompass approximately 2 km2 and follow Inca urban design. Also there is a conglomeration of common buildings clustered away from the plaza. Excavations and surface items suggest they were probably used for workshops and food preparation.[17] Most buildings are well-preserved and well-restored; restoration continues.

The terrain around the site was greatly modified. The central area of the site was leveled artificially and the surrounding hillsides were terraced to allow cultivation and small residential areas.[15] The typical Inca terraces form the largest constructions on site.

Many of the ceremonial structures are associated with water. There are two unusual temple wak'a sites that lie several hundred meters lower than the two plazas. These are carefully crafted step terraces down a steep slope are designed around water.[18] The site also contains a number of ceremonial structures such as the large usnu built on a truncated hill, the Giant Staircase, and an aqueduct providing water to the water shrines.[19]

Sectors

The archaeological complex of Choquequirao is divided into 12 sectors. While the contents of each sector are different, terraces used for various purposes are common throughout. It seems that most of the buildings here were either for ceremonial purposes, residences of the priests, or used to store food.

- Sector I is the highest and most northerly portion of the site. There are five buildings constructed on terraces at varying levels, a temple and a plaza, as well as a smaller plaza in the uppermost area of the sector. Two of the buildings appear to be qullqas (warehouses). The three long buildings, called kallankas were likely priests’ residences.[20]

- Sector II is where a majority of the qullqanpatas, or depositories are located. In one part of this sector there are 16 ceremonial platforms with canal routes in between that branch off from the main water way.[21]

- Sector III is between the hanan (high) area and the urin (low) area of the complex and contains what is believed to be the Haucaypata (Hawkaypata), or main plaza. At the periphery of the plaza there are one-story and two-story buildings. To the north, there is a Sunturwasi and a single level kallanka likely used for ceremony.[21] To the east are the buildings with two levels. The main plaza is discussed in more detail in the section called Ceremonial Center of this page.

- Sector IV is located in the southerly area of the complex, known as the urin zone. The main building here has walls that were probably ceremonial in function since one of them is known as “wall of offerings to the ancestors”.[21]

- Sector V is the location of the usnu which is a hill leveled at the summit to form an oval platform used for ceremony.[21] A small wall encircles the hill. From the platform, one can see the main plaza of sector III, the snow-capped mountains and the Apurímac River.

- Sector VI, south of the usnu in the urin area, it has the Wasi Kancha ("house yard"), also known as the priests' quarters. There are four terraces here that were used as ceremonial space.[22] In the walls of the terraces there is a zigzagged design.

- Sector VII can be reached from the main plaza by pathway. Located on the east side of Choquequirao, this zone contains cultivation terraces that have markedly greater amplitude than all others throughout the complex.

- Sector VIII, on the western side of the complex, has 80 cultivation terraces divided into plots by water canals that stream down from the main plaza. In this zone, one will find the famous "Llamas del Sol".[23]

- Sector IX contains general living quarters for groups of people, such as workers or families. The buildings are constructed on top of artificial platforms in circular and rectangular design, interconnected by stairways and narrow alleys.

- Sector X, called paraqtepata, has 18 terraced platforms that have irrigation canals running parallel to the stairs.[24]

- Sector XI has 80 terraces used for cultivation, called phaqchayuq ("the one with a waterfall"), which are the most extensive in the entire complex.[24] Also found here are small, quadrilateral enclosures with two levels used for both ceremony and living. Outside, there are three water fountains used for drinking and to supply the irrigation canals.

- Sector XII lies three hours away (by foot) from the upper part of the complex. Here there are 57 platforms with permanent irrigation systems. In the uppermost terraces there are buildings for ceremony and a pool of water fed by a spring. In the semicircular enclosures ceramic shards, stone tools and remains of bones have been found.[24]

Ceremonial center

The ceremonial center of Choquequirao shares many features similar to those of other Inca ceremonial centers and pilgrimage sites, such as Isla del Sol, Quespiwanka (Qhispi Wank'a, palace of Huayna Capac), Machu Picchu/Llaqtapata, Tipon and Saywite. The long and treacherous route from Cusco to Choquequirao likely passed by Machu Picchu, leading onto the face of Machu Picchu Peak. From Llaqtapata, the path continued down into the Mollepata Valley, traversed the Yanamia pass at 4670 m, and continued across the Rio Blanco, finally reaching Choquequirao from above after an estimated 7- to 10-day journey.[25]

The ceremonial center consists of a main platform and a lower plaza. Stone lined channels carried ceremonial water, or chicha to shrines and baths throughout the site. The main platform, unique in its size and prominence, limited ceremonial activity to royalty and the ministerial class. This seems as such due to evidence showing that the only entrance to the platform was through a double-jam doorway, which functioned to control access to the sacred space.[25] Other features of the ceremonial center include structures that mark the direction of certain solar events, such as when the June and December solstice sun rises and sets.

Located in the main platform, the Giant Stairway opens to the sunrise of the December solstice. Measured at 25 meters long and 4.4 meters wide, this structure seems to have been purely ceremonial in function, since the stairs end abruptly partway down a hill, leading to nothing. Large boulders that rest upon the risers of the stairway become fully illuminated when the December solstice sun rises. Gary R. Ziegler and J. McKim Malville have postulated that when the boulders become illuminated, a wak'a is activated by its solar camaquen—a case similar to when the large stone of the Torreon at Machu Picchu becomes illuminated.[25]

In the lower plaza a group of structures were found that appeared to be water shrines and baths. This belief is held based on their strong resemblance to those at sector II of Llaqtapata and because there are numerous water channels leading to that portion of the plaza.[25] Overall, it seems as though the site was chosen, as Machu Picchu was, for its sacred geographical location, and was designed to facilitate ritual and ceremonial activity.

Subsectors

The area around Choquequiaro contains several subsectors that have been associated with the Inca culture that thrived in Choquequirao, suggesting that the subsectors are most likely part of the site. Design, construction style, and cultural parallels support that these sectors were tightly intertwined with Choquequiaro and the Inca at some point in their history. The lack of residential space in these sectors suggests that these were probably farming outposts from Choquequirao rather than an independent site.[26] Due to differences in design and construction styles, it is believed that these sectors were built in three different phases.[27] Like Choquequirao art style, the subsector also contains multiple camelid art and ceremonial phaqchas that are tightly related to Inca, especially Pachacuti’s government.[28]

Materials

All lithic materials utilized for the construction of the site and surrounding sectors were mined from the local quarries.[29] Due to the metamorphic rock in the quarries of Choquequirao, superb masonry like that at Machu Picchu could not be obtained. Instead, the entrances and corners were shaped from quartzite, and the walls were made of ashlar and plastered with clay and then painted in a light orange color.[30]

Art

Most of the rock art in Choquequirao is in the terraced area where cultivation occurred. Archaeologists have documented twenty-five semi-naturalistic figures on the terraces of sector VIII of Choquequirao. The rocks used to build the walls are dark schist while the camelid images are of white calcocuarcita, a sandstone of quartz and carbonate.[31] The camelid motifs vary between a maximum height of 1.94 m and one minimum of 1.25 m.[32] In 2004, archaeologist Zenobio Valencia from the University of San Antonio Abad of Cusco found several camelid figurines made of white stones in a group of terraces in one sector of the archaeological site.[8]

One recent discovery for example, uncovered a scene laid into the stone terraces with white quartzite depicting several llamas loaded with cargo standing by their handlers. Present on the uppermost terrace wall is a zigzag pattern of the same quartzite. This style of design is uniquely Chachapoya and not found in other sites of Inca construction, indicating that workers from Chachapoya may have been involved in the construction of Choquequirao.[33]

Access

Presently the only way to access Choquequirao is by a hard hike. The common trailhead begins at the village of San Pedro de Cachora,[34] which is approximately a 4-hour drive from Cuzco, along the Cusco-Abancay route. Another access point is from Huanipaca village, whose crossroad is located on the same route Cusco-Abancay, 4–5 km beyond the Cachora crossroad. Huanipaca offers a 15 km trail, half distance less than Cachora trail (31 km). Over 5,000 people trekked to Choquequirao in 2013. From Choquequirao it is possible to continue hiking to Machu Picchu. Most treks range from 7-day to 11-day hikes, and involve going over the Yanama Pass, which at 4,668 m is the highest point on the trek.

The construction of the cable car to Choquequirao has been declared a priority by the Apurímac Regional Government, which are destined to receive 220 million Peruvian Soles (US$82.7 million) to fund the project. It will reduce a two-day hike to a 15-minute cable car ride.[35] Carlos Canales, president of the National Chamber of Tourism (Canatur) believes that in the first year of operation the Choquequirao cable car will receive 200,000 tourists, which will generate an income of US$4 million, with the average visitor paying US$20 per ticket.[36]

Photo gallery

- Twin buildings

- Large terraces

- Terraces, house and cascade

- Ruins and flora

- Ruins and flora

- Ruins and flora

- Building located in the main square of Choquequirao

See also

Notes

- ^ Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary) (5-vowel-system)

- ^ Ref Bertonio

- ^ Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- ^ Lee 1997

- ^ a b Choquequirao, Peru's Tourism Office, 2011

- ^ a b Trail to Choquequirao, El Comercio Newspaper, Lima, Peru, May 13, 2009, [Spanish] Archived April 16, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ "Peru: Choquequirao tops Lonely Planet's 'Best in Travel 2017' list".

- ^ a b Echevarría López 2009, p.213.

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, p.83.

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, p.82.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, pp.162-163.

- ^ Ethan Todras-Whitehill in the New York Times

- ^ Bingham, Hiram (1952). Lost City of the Incas. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 112–132. ISBN 9781842125854.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, pp.162–163.

- ^ a b Echevarría López 2009, p.214.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, p.162.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, pp.163-164.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, p. 164.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, p. 162.

- ^ Burga, Manuel.(2008). p. 103-104.

- ^ a b c d Burga, Manuel. (2008). p. 104.

- ^ Burga, Manuel. (2008). p. 104-105.

- ^ Burga, Manuel. (2008). p. 105.

- ^ a b c Burga, Manuel. (2008). p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Ziegler 2011, p.167.

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, pp.81-82

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, p.77.

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, pp.81-82.

- ^ Echevarría López 2008, p.72

- ^ Ziegler 2011, pp.164-165.

- ^ Echevarría López 2009, pp.214-215.

- ^ Echevarría López 2009, p.216.

- ^ Ziegler 2011, p.165.

- ^ Trekking To Machu Picchu, Horizon Guides, 2017

- ^ Salazar, Carla. "Tramway planned for Machu Picchu's 'sister city'". AP Travel. Associated Press. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Choquequirao recibiría 600 mil viajeros en el 2018 con teleférico". El Comercio. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

References

- Burga, Manuel (2008). Choquequirao; símbolo de la resistencia andina (historia, antropología y linguística). Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. pp. 103–106. ISBN 978-9972-46-390-7.

- Echevarría López, Gori Tumi; Zenobio Valencia García (2009). "The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th century Cusco imperial rock art". Rock Art Research. 26 (2): 213–223.

- Echevarría López, Gori Tumi; Zenobio Valencia García (2008). "Arqutectura y contexto arqueológico Sector VIII, andenes <<Las Llamas>> de Choquequirao". Investigaciones Sociales (20): 63–83.

- Ziegler, Gary R.and J. McKim Malville. Choquequirao, Topa Inca's Machu Picchu: a royal estate and ceremonial center|journal=Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 2011, number 278, pages 162–168.

- Ziegler, Gary R and J Mckim Malville.(2013). Machu Picchu's Sacred Sisters; Choquequirao and Llactapata; Astronomy, Symbolism and Sacred Geography in the Inca Heartland. Johnson Books, Boulder.

- Ziegler, Gary R. Beyond Machu Picchu; Lost City in the Clouds, Peruvian Times. https://www.peruviantimes.com/06/beyond-machu-picchu-choquequirao-lost-city-in-the-clouds/23519/

- Lee, Vincent R. (1997). Inca Choqek'iraw: New Work at a Long Known Site. Cortez, CO:Sixpac Manco Publications.

- Choquequirao, Peru's Tourism Office, 2011

- Trail to Choquequirao, El Comercio Newspaper, Lima, Peru, May 13, 2009, [Spanish]

- Cusco travel guide, September 5, 2011, [Spanish]

- The Other Machu Picchu article on Choquequirao (The New York Times, June 3, 2007)

- Jones, Paul. Exciting News about the Choquequirao Cable Car. Totally Latin America. S.A. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Salazar, Carla. Tramway planned for Machu Picchu’s 'sister city'. AP Travel. Associated Press. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Choquequirao recibiría 600 mil viajeros en el 2018 con teleférico. El Comercio. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

External links

- The Other Machu Picchu article on Choquequirao (The New York Times, June 3, 2007)

- Debate on the value of publicizing Choquequirao as a travel destination from the author of the New York Times article