Cayley–Klein metric

In mathematics, a Cayley–Klein metric is a metric on the complement of a fixed quadric in a projective space which is defined using a cross-ratio. The construction originated with Arthur Cayley's essay "On the theory of distance"[1] where he calls the quadric the absolute. The construction was developed in further detail by Felix Klein in papers in 1871 and 1873, and subsequent books and papers.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] The Cayley–Klein metrics are a unifying idea in geometry since the method is used to provide metrics in hyperbolic geometry, elliptic geometry, and Euclidean geometry. The field of non-Euclidean geometry rests largely on the footing provided by Cayley–Klein metrics.

Foundations

The algebra of throws by Karl von Staudt (1847) is an approach to geometry that is independent of metric. The idea was to use the relation of projective harmonic conjugates and cross-ratios as fundamental to the measure on a line.[10] Another important insight was the Laguerre formula by Edmond Laguerre (1853), who showed that the Euclidean angle between two lines can be expressed as the logarithm of a cross-ratio.[11] Eventually, Cayley (1859) formulated relations to express distance in terms of a projective metric, and related them to general quadrics or conics serving as the absolute of the geometry.[12][13] Klein (1871, 1873) removed the last remnants of metric concepts from von Staudt's work and combined it with Cayley's theory, in order to base Cayley's new metric on logarithm and the cross-ratio as a number generated by the geometric arrangement of four points.[14] This procedure is necessary to avoid a circular definition of distance if cross-ratio is merely a double ratio of previously defined distances.[15] In particular, he showed that non-Euclidean geometries can be based on the Cayley–Klein metric.[16]

Cayley–Klein geometry is the study of the group of motions that leave the Cayley–Klein metric invariant. It depends upon the selection of a quadric or conic that becomes the absolute of the space. This group is obtained as the collineations for which the absolute is stable. Indeed, cross-ratio is invariant under any collineation, and the stable absolute enables the metric comparison, which will be equality. For example, the unit circle is the absolute of the Poincaré disk model and the Beltrami–Klein model in hyperbolic geometry. Similarly, the real line is the absolute of the Poincaré half-plane model.

The extent of Cayley–Klein geometry was summarized by Horst and Rolf Struve in 2004:[17]

- There are three absolutes in the real projective line, seven in the real projective plane, and 18 in real projective space. All classical non-Euclidean projective spaces as hyperbolic, elliptic, Galilean and Minkowskian and their duals can be defined this way.

Cayley-Klein Voronoi diagrams are affine diagrams with linear hyperplane bisectors.[18]

Cross ratio and distance

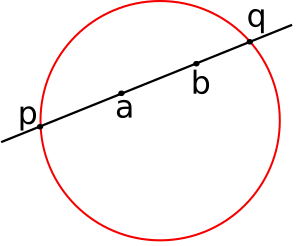

Cayley–Klein metric is first illustrated on the real projective line P(R) and projective coordinates. Ordinarily projective geometry is not associated with metric geometry, but a device with homography and natural logarithm makes the connection. Start with two points p and q on P(R). In the canonical embedding they are [p:1] and [q:1]. The homographic map

takes p to zero and q to infinity. Furthermore, the midpoint (p+q)/2 goes to [1:1]. The natural logarithm takes the image of the interval [p,q] to the real line, with the log of the image of the midpoint being 0.

For the distance between two points in the interval, the Cayley–Klein metric uses the logarithm of the ratio of the points. As a ratio is preserved when numerator and denominator are equally re-proportioned, so the logarithm of such ratios is preserved. This flexibility of ratios enables the movement of the zero point for distance: To move it to a, apply the above homography, say obtaining w. Then form this homography:

- which takes [w,1] to [1 : 1].

The composition of the first and second homographies takes a to 1, thus normalizing an arbitrary a in the interval. The composed homographies are called the cross ratio homography of p, q and a. Frequently cross ratio is introduced as a function of four values. Here three define a homography and the fourth is the argument of the homography. The distance of this fourth point from 0 is the logarithm of the evaluated homography.

In a projective space containing P(R), suppose a conic K is given, with p and q on K. A homography on the larger space may have K as an invariant set as it permutes the points of the space. Such a homography induces one on P(R), and since p and q stay on K, the cross ratio remains invariant. The higher homographies provide motions of the region bounded by K, with the motion preserving distance, an isometry.

Disk applications

Suppose a unit circle is selected for the absolute. It may be in P2(R) as

- which corresponds to

On the other hand, the unit circle in the ordinary complex plane

- uses complex number arithmetic

and is found in the complex projective line P(C), something different from the real projective plane P2(R). The distance notion for P(R) introduced in the previous section is available since P(R) is included in both P2(R) and P(C). Say a and b are interior to the circle in P2(R). Then they lie on a line which intersects the circle at p and q. The distance from a to b is the logarithm of the value of the homography, generated above by p, q, and a, when applied to b. In this instance the geodesics in the disk are line segments.

On the other hand, geodesics are arcs of generalized circles in the disk of the complex plane. This class of curves is permuted by Möbius transformations, the source of the motions of this disk that leave the unit circle as an invariant set. Given a and b in this disk, there is a unique generalized circle that meets the unit circle at right angles, say intersecting it at p and q. Again, for the distance from a to b one first constructs the homography for p, q, and a, then evaluates it at b, and finally uses logarithm. The two models of the hyperbolic plane obtained in this fashion are the Cayley–Klein model and the Poincaré disk model.

Special relativity

In his lectures on the history of mathematics from 1919/20, published posthumously 1926, Klein wrote:[19]

- The case in the four-dimensional world or (to remain in three dimensions and use homogeneous coordinates) has recently won special significance through the relativity theory of physics.

That is, the absolutes or in hyperbolic geometry (as discussed above), correspond to the intervals or in spacetime, and its transformation leaving the absolute invariant can be related to Lorentz transformations. Similarly, the equations of the unit circle or unit sphere in hyperbolic geometry correspond to physical velocities or in relativity, which are bounded by the speed of light c, so that for any physical velocity v, the ratio v/c is confined to the interior of a unit sphere, and the surface of the sphere forms the Cayley absolute for the geometry.

Additional details about the relation between the Cayley–Klein metric for hyperbolic space and Minkowski space of special relativity were pointed out by Klein in 1910,[20] as well as in the 1928 edition of his lectures on non-Euclidean geometry.[21]

Affine CK-geometry

In 2008 Horst Martini and Margarita Spirova generalized the first of Clifford's circle theorems and other Euclidean geometry using affine geometry associated with the Cayley absolute:

- If the absolute contains a line, then one obtains a subfamily of affine Cayley–Klein geometries. If the absolute consists of a line f and a point F on f, then we have the isotropic geometry. An isotropic circle is a conic touching f at F.[22]

Use homogeneous coordinates (x,y,z). Line f at infinity is z = 0. If F = (0,1,0), then a parabola with diameter parallel to y-axis is an isotropic circle.

Let P = (1,0,0) and Q = (0,1,0) be on the absolute, so f is as above. A rectangular hyperbola in the (x,y) plane is considered to pass through P and Q on the line at infinity. These curves are the pseudo-Euclidean circles.

The treatment by Martini and Spirova uses dual numbers for the isotropic geometry and split-complex numbers for the pseudo-Euclidean geometry. These generalized complex numbers associate with their geometries as ordinary complex numbers do with Euclidean geometry.

History

Cayley

The question recently arose in conversation whether a dissertation of 2 lines could deserve and get a Fellowship. ... Cayley's projective definition of length is a clear case if we may interpret "2 lines" with reasonable latitude. ... With Cayley the importance of the idea is obvious at first sight.

Arthur Cayley (1859) defined the "absolute" upon which he based his projective metric as a general equation of a surface of second degree in terms of homogeneous coordinates:[1]

| original | modern |

|---|---|

The distance between two points is then given by

| original | modern |

|---|---|

In two dimensions

| original | modern |

|---|---|

with the distance

| original | modern |

|---|---|

of which he discussed the special case with the distance

He also alluded to the case (unit sphere).

Klein

Felix Klein (1871) reformulated Cayley's expressions as follows: He wrote the absolute (which he called fundamental conic section) in terms of homogeneous coordinates:[23]

| original | modern |

|---|---|

and by forming the absolutes and for two elements, he defined the metrical distance between them in terms of the cross ratio:

| original | modern |

|---|---|

In the plane, the same relations for metrical distances hold, except that and are now related to three coordinates each. As fundamental conic section he discussed the special case , which relates to hyperbolic geometry when real, and to elliptic geometry when imaginary.[24] The transformations leaving invariant this form represent motions in the respective non–Euclidean space. Alternatively, he used the equation of the circle in the form , which relates to hyperbolic geometry when is positive (Beltrami–Klein model) or to elliptic geometry when is negative.[25] In space, he discussed fundamental surfaces of second degree, according to which imaginary ones refer to elliptic geometry, real and rectilinear ones correspond to a one-sheet hyperboloid with no relation to one of the three main geometries, while real and non-rectilinear ones refer to hyperbolic space.

In his 1873 paper he pointed out the relation between the Cayley metric and transformation groups.[26] In particular, quadratic equations with real coefficients, corresponding to surfaces of second degree, can be transformed into a sum of squares, of which the difference between the number of positive and negative signs remains equal (this is now called Sylvester's law of inertia). If the sign of all squares is the same, the surface is imaginary with positive curvature. If one sign differs from the others, the surface becomes an ellipsoid or two-sheet hyperboloid with negative curvature.

In the first volume of his lectures on non-Euclidean geometry in the winter semester 1889/90 (published 1892/1893), he discussed the non-Euclidean plane, using these expressions for the absolute:[27] and discussed their invariance with respect to collineations and Möbius transformations representing motions in non-Euclidean spaces.

In the second volume containing the lectures of the summer semester 1890 (also published 1892/1893), Klein discussed non-Euclidean space with the Cayley metric[28] and went on to show that variants of this quaternary quadratic form can be brought into one of the following five forms by real linear transformations[29]

The form was used by Klein as the Cayley absolute of elliptic geometry,[30] while to hyperbolic geometry he related and alternatively the equation of the unit sphere .[31] He eventually discussed their invariance with respect to collineations and Möbius transformations representing motions in Non-Euclidean spaces.

Robert Fricke and Klein summarized all of this in the introduction to the first volume of lectures on automorphic functions in 1897, in which they used as the absolute in plane geometry, and as well as for hyperbolic space.[32] Klein's lectures on non-Euclidean geometry were posthumously republished as one volume and significantly edited by Walther Rosemann in 1928.[9] An historical analysis of Klein's work on non-Euclidean geometry was given by A'Campo and Papadopoulos (2014).[16]

See also

Citations

- ^ a b Cayley (1859), p. 82, §§209–229

- ^ Klein (1871)

- ^ Klein (1873)

- ^ Klein (1893a)

- ^ Klein (1893b)

- ^ Fricke & Klein (1897)

- ^ Klein (1910)

- ^ Klein (1926)

- ^ a b Klein (1928)

- ^ Klein (1928), p. 163

- ^ Klein (1928), p. 138

- ^ Klein (1928), p. 303

- ^ Pierpont (1930), p. 67ff

- ^ Klein (1928), pp. 163, 304

- ^ Russell (1898), p. 32

- ^ a b A'Campo & Papadopoulos (2014)

- ^ Struve & Struve (2004), p. 157

- ^ Nielsen (2016)

- ^ Klein (1926), p. 138

- ^ Klein (1910)

- ^ Klein (1928), chapter XI, §5

- ^ Martini & Spirova (2008)

- ^ Klein (1871), p. 587

- ^ Klein (1871), p. 601

- ^ Klein (1871), p. 618

- ^ Klein (1873), §7

- ^ Klein (1893a), pp. 64, 94, 109, 138

- ^ Klein (1893b), p. 61

- ^ Klein (1893b), p. 64

- ^ Klein (1893b), pp. 76ff, 108ff

- ^ Klein (1893b), pp. 82ff, 142ff

- ^ Fricke & Klein (1897), pp. 1–60, Introduction

References

Historical

- von Staudt, K. (1847). Geometrie der Lage. Nürnberg: Nürnberg F. Korn.

- Laguerre, E. (1853). "Note sur la théorie des foyers". Nouvelles annales de mathématiques. 12: 57–66.

- Cayley, A. (1859). "A sixth memoir upon quantics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 149: 61–90. doi:10.1098/rstl.1859.0004.

- Klein, F. (1871). "Ueber die sogenannte Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie". Mathematische Annalen. 4 (4): 573–625. doi:10.1007/BF02100583. S2CID 119465069.

- Klein, F. (1873). "Ueber die sogenannte Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie". Mathematische Annalen. 6 (2): 112–145. doi:10.1007/BF01443189. S2CID 123810749.

- Klein, F. (1893a). Schilling, Fr. (ed.). Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie I, Vorlesung gehalten während des Wintersemesters 1889–90. Göttingen.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (second print, first print in 1892) - Klein, F. (1893b). Schilling, Fr. (ed.). Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie II, Vorlesung gehalten während des Sommersemesters 1890. Göttingen.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (second print, first print in 1892)

Secondary sources

- Killing, W. (1885). Die nicht-euklidischen Raumformen. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Fricke, R.; Klein, F. (1897). Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen – Erster Band: Die gruppentheoretischen Grundlagen. Leipzig: Teubner.

- Russell, Bertrand (1898), An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry re-issued 1956 by Dover Publications, Inc.

- Alfred North Whitehead (1898) Universal Algebra, Book VI Chapter 1: Theory of Distance, pp. 347–70, especially Section 199 Cayley's Theory of Distance.

- Hausdorff, F. (1899). "Analytische Beiträge zur nichteuklidischen Geometrie". Leipziger Math.-Phys. Berichte. 51: 161–214. hdl:2027/hvd.32044092889328.

- Duncan Sommerville (1910/11) "Cayley–Klein metrics in n-dimensional space", Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society 28:25–41.

- Klein, Felix (1921). . Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung. 19: 533–552. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-51960-4_31. ISBN 978-3-642-51898-0. Reprinted in Klein, Felix (1921). Gesammelte mathematische Abhandlungen. Vol. 1. pp. 533–552. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-51960-4_31. English translation by David Delphenich: On the geometric foundations of the Lorentz group

- Veblen, O.; Young, J.W. (1918). Projective geometry. Boston: Ginn.

- Liebmann, H. (1923). Nichteuklidische Geometrie. Berlin & Leipzig: Berlin W. de Gruyter.

- Klein, F. (1926). Courant, R.; Neugebauer, O. (eds.). Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Springer.; English translation: Development of Mathematics in the 19th Century by M. Ackerman, Math Sci Press

- Klein, F. (1928). Rosemann, W. (ed.). Vorlesungen über nicht-Euklidische Geometrie. Berlin: Springer.

- Pierpont, J. (1930). "Non-euclidean geometry, a retrospect" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 36 (2): 66–76. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1930-04885-5.

- Littlewood, J. E. (1986) [1953], Littlewood's miscellany, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-33058-9, MR 0872858

- Harvey Lipkin (1985) Metrical Geometry from Georgia Institute of Technology

- Struve, Horst; Struve, Rolf (2004), "Projective spaces with Cayley–Klein metrics", Journal of Geometry, 81 (1): 155–167, doi:10.1007/s00022-004-1679-5, ISSN 0047-2468, MR 2134074, S2CID 121783102

- Martini, Horst; Spirova, Margarita (2008). "Circle geometry in affine Cayley–Klein planes". Periodica Mathematica Hungarica. 57 (2): 197–206. doi:10.1007/s10998-008-8197-5. S2CID 31045705.

- Struve, Horst; Struve, Rolf (2010), "Non-euclidean geometries: the Cayley–Klein approach", Journal of Geometry, 89 (1): 151–170, doi:10.1007/s00022-010-0053-z, ISSN 0047-2468, MR 2739193, S2CID 123015988

- A'Campo, N.; Papadopoulos, A. (2014). "On Klein's So-called Non-Euclidean geometry". In Ji, L.; Papadopoulos, A. (eds.). Sophus Lie and Felix Klein: The Erlangen Program and Its Impact in Mathematics and Physics. pp. 91–136. arXiv:1406.7309. doi:10.4171/148-1/5. ISBN 978-3-03719-148-4. S2CID 6389531.

- Nielsen, Frank; Muzellec, Boris; Nock, Richard (2016), "Classification with mixtures of curved mahalanobis metrics", 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), pp. 241–245, doi:10.1109/ICIP.2016.7532355, ISBN 978-1-4673-9961-6, S2CID 7481968

Further reading

- Drösler, Jan (1979), "Foundations of multidimensional metric scaling in Cayley–Klein geometries", British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 32 (2): 185–211

![{\displaystyle [z:1]{\begin{pmatrix}-1&1\\p&-q\end{pmatrix}}=[p-z:z-q]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/60c0af350e3015b584d15d8cfe1b51d2b5b3bb7b)

![{\displaystyle [z:1]{\begin{pmatrix}1&0\\0&w\end{pmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd288fb6c50a9286e6732d3bd0a83ab9fa7bb15a)

![{\displaystyle \{[x:y:z]:x^{2}+y^{2}=z^{2}\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0724641be3f1284f43ef62f2b14ffed638c32e53)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{c}\cos ^{-1}{\dfrac {\sum a_{\alpha \beta }x_{\alpha }y_{\beta }}{{\sqrt {\sum a_{\alpha \beta }x_{\alpha }x_{\beta }}}{\sqrt {\sum a_{\alpha \beta }y_{\alpha }y_{\beta }}}}}\\\left[\alpha ,\beta =1,2\right]\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9298d221f7c193903e8bee1506ef0b977295dce6)