Berea College

Official logo of Berea College | |

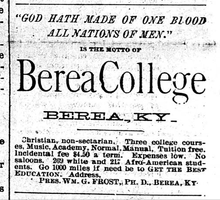

| Motto | God has made of one blood all peoples of the earth.[1] |

|---|---|

| Type | Private liberal arts work college |

| Established | 1855 |

Academic affiliations | Space-grant |

| Endowment | $1.2 billion[2] (2021) |

| President | Cheryl L. Nixon |

Academic staff | 139[3] |

| Undergraduates | 1,454[4] |

| Location | ,, United States 37°34′23″N 84°17′31″W / 37.573°N 84.292°W |

| Campus | Exurban (140 acres) |

| Colors | Blue and White |

| Nickname | Mountaineers |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III—HCAC |

| Website | berea |

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated.[5] It was integrated from as early as 1866 until 1904, and again after 1954.[6]

The college provides a work-study grant that covers the remaining tuition fees after subtracting the total sum a student received from Pell Grant, other grants, and scholarships.[7][8][9] Berea's primary service region is southern Appalachia but students come from more than 40 states in the United States and 70 other countries. Approximately one in three students identify as people of color.

Berea offers bachelor's degrees in 33 majors. It incorporates a mandatory work-study program that requires students to engage in a minimum of 10 hours per week of work for the college.[8]

History

Founded in 1855 by the abolitionist and Augusta College graduate John Gregg Fee (1816–1901), Berea College admitted both black and white students in a fully integrated curriculum, making it the first non-segregated, coeducational college in the South and one of a handful of institutions of higher learning to admit both male and female students in the mid-19th century.[10] The college began as a one-room schoolhouse that also served as a church on Sundays on land that was granted to Fee by politician and abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay. Fee named the new community after the biblical Berea. Although the school's first articles of incorporation were adopted in 1859, founder John Gregg Fee and the teachers were forced out of the area by pro-slavery supporters in that same year.

Fee spent the Civil War years raising funds for the school, trying to provide for his family in Cincinnati, Ohio, and working at Camp Nelson. He returned afterward to continue his work at Berea. He spent nearly 18 months working mostly at Camp Nelson, where he helped provide facilities for the freedmen and their families, as well as teaching and preaching. He helped get funds for barracks, a hospital, school and church.

In 1866, Berea's first full year after the war, it had 187 students, 96 Black and 91 white. It began with preparatory classes to ready students for advanced study at the college level. In 1869, the first college students were admitted, and the first bachelor's degrees were awarded in 1873. Almost all the private and state colleges in the South were racially segregated. Berea was the main exception until a new state law in 1904 forced its segregation.[11] The college challenged the law in state court and further appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in Berea College v. Kentucky. When the challenge failed, the college had to become a segregated all-white school, but it raised funds to establish the Lincoln Institute in 1912 in Simpsonville, Kentucky, to educate Black students.[10] In 1950, when the Day Law was amended to allow integration of schools at the college level, Berea promptly resumed its integrated policies.[10]

In 1911 the college restricted students to eating at college-owned facilities. A local businessman sued but the Kentucky Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling that the college's restriction was legal. (Gott v. Berea College).

In 1925, famed advertiser Bruce Barton, a future congressman, sent a letter to 24 wealthy men in America to raise funds for the college. Every single letter was returned with a minimum of $1,000 in donation. During World War II, Berea was one of 131 colleges nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a navy commission.[12]

Prior to 1968, Berea provided pre-college education in addition to college level curriculum. That year, the elementary and secondary schools (Foundation School) were discontinued in favor of focusing on undergraduate college education.[13]

Presidents

| Name | Years as president | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Henry Fairchild | (1869–1889)[10] |

| 2 | William Boyd Stewart | (1890–1892) |

| 3 | William Goodell Frost | (1892–1920) |

| 4 | William J. Hutchins | (1920–1939) |

| 5 | Francis S. Hutchins | (1939–1967) |

| 6 | Willis D. Weatherford | (1967–1984) |

| 7 | John B. Stephenson | (1984–1994) |

| 8 | Larry Shinn | (1994–2012) |

| 9 | Lyle D. Roelofs | (2012–2023)[14] |

| 10 | Cheryl Nixon | (2023–Present)[15] |

Source:[16]

Academics

Berea College offers 33 majors and 39 minors from which its 1,600 students can choose. Students who wish to pursue a field of study that cannot be met through an established Berea College major have the option to submit a proposal for an independent major, provided they meet the criteria in the college catalog's definition of a major. The student must secure independent major advisers (primary and secondary). Its most popular majors, based on 2021 graduates, were:[17]

- Business Administration and Management (30)

- Computer and Information Sciences (28)

- Biology/Biological Sciences (21)

- Psychology (20)

- Human Development and Family Studies (19)

- Mass Communication/Media Studies (16)

- Engineering Technologies/Technicians (14)

- Political Science and Government (14)

To ensure every student has access to fully experience a liberal arts education, the college provides significant funding to assist students in studying abroad.[18] Berea students are also eligible to win the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, which provides funding for a year of study abroad following graduation.[19] Like many private colleges, Berea does not enroll students based upon semester hours. Berea College uses a course credit system, which has the following equivalencies:

- A 0.25 credit course is the equivalent of 1 semester hour.

- A 0.50 credit course is the equivalent of 2 semester hours.

- A 0.75 credit course is equivalent to 3 semester hours.

- A 1.00 credit course is the equivalent to 4 semester hours.[20]

All students are required to attend the college on a full-time basis, which is 3.00 course credits of enrollment, or 12 semester hours. Students must be enrolled in at least 4.00 course credits to be considered for the Dean's list. Enrollment in 4.75 or more course credits requires the approval of the Academic Adviser, and a minimum cumulative GPA of 3.30. There are also optional Summer opportunities to engage in study. Students may take between 1 and 2.25 credits during Summer. One Berea course credit is equivalent to four semester hours (6 quarter hours). Part-time enrollment is not permitted except during Summer term. A cumulative GPA of 2.0 is required in all majors in order to graduate with a bachelor's degree.

Students are required to attend at least 7 convocation events each semester and receive academic credit. The convocations are designed as a supplement to the curriculum by encouraging educational experience and cultural enrichment. Topics range across academic fields and include lectures, symposia, concerts, and the performing arts. These events are free to Berea College students and open to the public.[21]

Rankings and outcomes

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[22] | 30 |

| Washington Monthly[23] | 1 |

| National | |

| Forbes[24] | 453 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[25] | 231 |

In 2024, Washington Monthly ranked Berea College first in the U.S. among national liberal arts colleges based on its contribution to the public good, as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.[26] The 2022 annual ranking of U.S. News & World Report categorizes Berea as 'more selective' and rates it 30th overall, first in "Service Learning," second for "Most Innovative Schools," tied for 13th in "Best Undergraduate Teaching" and tied for sixth in "Top Performers in Social Mobility" among liberal arts colleges in the U.S.[27][28] Kiplinger's Personal Finance places Berea 35th in its 2019 ranking of 149 best value liberal arts colleges in the United States.[29]

According 2022 data from College Scorecard, Berea College graduates earn a median salary of $40,000 ten years after their entry into the institution.[30][31] Mathematics majors earn around $18,000, biology $29,000, psychology $35,000, and nursing $57,000.[32] 51% of Berea graduates earn higher than a typical high school graduate of the corresponding area.[30]

Scholarships and work program

Berea College provides all students with full-tuition scholarships and many receive support for room and board as well. Berea College charges no tuition beyond the total amount a student receives in Pell Grant and other grants and scholarships. Every admitted student at Berea College is granted the equivalent of a four-year, full-tuition scholarship that covers the remaining tuition fees after deducting any grants and scholarships the student may have received. Admission to the college is granted only to students who need financial assistance (as determined by the FAFSA); in general, applications are accepted only from those whose family income falls within the bottom 40% of U.S. households. About 75% of the college's incoming class is drawn from the Appalachian region of the South and some adjoining areas, and about 8% are international students. Generally, no more than one student is admitted from a given country in a single year (with the exception of countries in distress such as Liberia). This policy ensures that 70 or more nationalities are usually represented in the student body of Berea College. All international students are admitted on full scholarships with the same regard for financial need as U.S. students.[33]

In order to support its extensive scholarship program, Berea College has one of the largest financial reserves of any American college when measured on a per-student basis. The endowment was $1.6 billion as of June 30, 2021.[34] The base of Berea College's finances is dependent on substantial contributions from alumni and from individuals, foundations, and corporations that support the mission of the college. A solid investment strategy increased the endowment from $150 million (~$361 million in 2023) in 1985 to its current amount.[35]

In 2017 the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act enacted an excise tax of 1.4% of endowment incomes that exceed net assets of at least $500,000 per student. Due to the size of Berea's endowment and number of full-time enrolled students, this tax bill would have reduced the number of students it could serve. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 provided an exemption for colleges and universities with fewer than 500 tuition-paying students, making Berea College exempt as it provides tuition-free education to all students.[36]

As a work college, Berea has a student work program in which all students work on campus 10 or more hours per week. Berea is one of nine federally recognized work colleges in the United States and one of two in Kentucky (Alice Lloyd College being the other) to have mandatory work study programs. Employment opportunities range from busing tables at the Boone Tavern Hotel, a historic business owned by the college, to leading campus tours for visitors and prospective students, or making brooms, ceramics and woven items in Student Craft. Other job duties include janitorial labor, building management, resident assistant, teaching assistant, food service, gardening and grounds keeping, information technology, woodworking, and secretarial work. Berea College has helped make the town a center for quality arts and crafts.[37]

As of 2022, students are paid an hourly wage from $5.60 to $8.60 by the college, based on the WLS ("Work, Learning, and Service") level attached to individual labor positions.[38] The college regularly increases student pay on a yearly basis, but it has never been equivalent to the federal minimum wage in the school's history. Because of the scheduling demands of both an academic requirement and a labor requirement, students are not allowed to work at off-campus jobs.

Christian identity

Berea was founded by Protestant Christians. It maintains a Christian identity separate from any particular denomination. The college's motto, "God has made of one blood all peoples of the earth," is taken from Acts 17:26. One General Studies course is focused on Christian faith, as every student is required to take an Understandings of Christianity course. In an effort to be sensitive to the diverse preferences and experiences of students and faculty, these courses are designed to be taught with respect for the unique spiritual journey of each individual, regardless of religious identification.

Library collections

The Hutchins Library maintains an extensive collection of books, archives, and music pertaining to the history and culture of the Southern Appalachian region. The Southern Appalachian Archives contain organizational records, personal papers, oral histories, and photographs. Included are the papers of the Council of the Southern Mountains (1912–1989) and the Appalachian Volunteers (1963–1970).

Student life

Since 2002, all students at Berea have received laptops that they take with them when they graduate. Students are not required to pay for the computers, though they do provide a small fee to support the technological infrastructure. Students must have a special permit to have a car on campus. Such permits are rarely granted to first- or second-year students.

Since 1875, Berea College celebrates Mountain Day, a holiday set aside to enjoy being together in nature. Students take off from classes for a sunrise hike to the top of the Pinnacle Mountain and engage in games, performances, food, and other festivities.[39] Another unique holiday to Berea College is Labor Day, where the campus takes a break from classes to recognize and celebrate the value of student work. Established in 1921, it has expanded to help students find labor placements for the following academic year and soon-to-be graduates prepare for life after college.[40]

Athletics

The Berea athletic teams are called the Mountaineers. The college is a member of Division III of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and joined the Heartland Collegiate Athletic Conference (HCAC) in July 2024 after two years in the Collegiate Conference of the South (CCS). They were also a member of the United States Collegiate Athletic Association (USCAA). The Mountaineers previously competed in the USA South Athletic Conference (USA South) from 2017–18 to 2021–22; as an NCAA D-III Independent from 2014–15 to 2016–17; and in the Kentucky Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (KIAC; now currently known as the River States Conference (RSC) since the 2016–17 school year) of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) from 1916–17 to 2013–14.

Berea competes in 14 intercollegiate varsity sports: Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, golf, soccer, tennis and track & field; while women's sports include basketball, cross country, soccer, softball, tennis, track & field and volleyball.[41]

Move to NCAA Division III

On February 20, 2012, the NCAA announced it had granted Berea permission to begin a one-year period exploring membership in its Division III, non-scholarship athletic program.[42]

On May 4, 2016, the USA South announced that Berea would join the league effective in the 2017–18 school year.[43]

Joining the CCS

The USA South announced in February 2022 that it would split into two leagues the following July, with eight of its then 19 members, including Berea, establishing the new Collegiate Conference of the South.[44]

Move to the HCAC

On June 1, 2023, Berea and the Heartland Collegiate Athletic Conference announced that the Mountaineers would join that league after the 2023–24 school year.[45]

Men's basketball

On February 4, 1954, Irvine Shanks was in the lineup for Berea against Ohio Wilmington, breaking the color barrier in college basketball in Kentucky.

Notable alumni and faculty

- Daniel S. Bentley (1850–1916), American minister, writer, newspaper founder[10]

- John "Bam" Carney – educator; member of the Kentucky House of Representatives from Campbellsville

- Dean W. Colvard – former president of Mississippi State University, notable for his role in a 1963 controversy surrounding the participation of the university's basketball team in the NCAA Tournament

- John Courter – educator; an American composer, organist, and carillonneur, considered one of the leading contemporary composers for the carillon

- John Fenn – recipient of 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Despite his future success, Fenn always felt that he was limited by the lack of meaningful math education in his undergrad years.[46] [47]

- Derby Chukwudi - Miss New Jersey USA 2023

- Finley Hamilton – United States Representative from Kentucky.[48]

- Alix E. Harrow — sci-fi writer and winner of a 2019 Hugo Award.

- bell hooks (Gloria Jean Watkins) – Distinguished Professor in Residence in Appalachian Studies, author of over thirty books[49]

- Julia Britton Hooks – second African-American woman in the United States to graduate from college and paternal grandmother of Benjamin Hooks

- Silas House – NEH Chair in Appalachian Studies, author and activist[50]

- Akilah Hughes – Writer, comedian, YouTuber, podcaster, and actress

- George Samuel Hurst - A health physicist and professor of physics at the University of Kentucky[51]

- Juanita M. Kreps – U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President Jimmy Carter

- C.E. Morgan – author of All the Living[52] and The Sport of Kings[53]

- Tharon Musser – Tony Award-winning lighting designer known especially for her work on A Chorus Line

- Rude Osolnik (1915–2001) woodturner, educator[54][55]

- Willie Parker – abortion provider and reproductive rights activist[56]

- K.C. Potter – academic administrator and LGBT rights activist

- Jeffrey Reddick – American screenwriter, best known for creating the Final Destination series[57]

- Jack Roush – founder, CEO, and owner of Roush Fenway Racing, a NASCAR team

- Green Pinckney Russell (1861–1939), American school administrator, college president, and teacher[58]

- Tijan Sallah - Gambian poet, short story writer, biographer and economist at the World Bank

- Helen Maynor Scheirbeck – Assistant Director for Public Programs at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian

- Chasteen C. Stumm (1848–1895) minister, newspaper journalist, publisher, teacher; attended Berea but did not graduate[59]

- Djuan Trent – Miss Kentucky 2010

- Horace M. Trent - American physicist[60]

- Rocky Tuan – Vice-chancellor of The Chinese University of Hong Kong

- C. C. Vaughn - Kentucky educator and minister

- Muse Watson – American actor[61]

- Billy Edd Wheeler – songwriter, performer and writer

- Carter G. Woodson – African American historian, author, journalist and co-founder of Black History Month

References

- ^ "Our Motto". Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ As of June 30, 2021. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Faculty Fall 2021" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Enrollment Fall 2021" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Our Inclusive History". www.berea.edu. Berea College. June 28, 2022. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022.

- ^ Wills, Matthew (August 20, 2021). "How a Southern College Tried to Resist Segregation". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Funding Opportunities". www.berea.edu. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Berea College. "Earnings from Work". berea.smartcatalogiq.com. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Cost of Attendance". www.berea.edu. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Gerald L.; McDaniel, Karen Cotton; Hardin, John A. (August 28, 2015). The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8131-6066-5.

- ^ Richard Allen Heckman and Betty Jean Hall. "Berea College and the Day Law." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 66.1 (1968): 35–52. in JSTOR Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Navy V-12 List of Deceased". Berea, Kentucky: Berea College. 2011. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ "About Berea College - History". Berea College. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Lyle Roelofs: A Presidential Report Card – Berea College Magazine". magazine.berea.edu. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ ">. www.berea.edu. Retrieved July 1, 2023. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Berea College Early History". Berea College. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Berea College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Center for International Education: Berea College". Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "Thomas J. Watson Fellowship: CIE-Berea College". Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "Academic Services Advisor Guide: Berea College". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "About Convocations". Berea College. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Ranking". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Best National Liberal Arts Colleges". US News & World Report. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Top Universities Impacting Social Mobility". US News & World Report. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Kiplinger's Best College Values". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. July 2019. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "College Scorecard: Berea College". collegescorecard.ed.gov. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Berea College: US News and World Report".

- ^ "Data Home | College Scorecard". collegescorecard.ed.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Admission Requirements: Prospective Students". Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ As of June 30, 2018. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2017 to FY 2018" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ Brull, Steven. (September 2005). "Appalachian spring". Institutional Investor, p. 35.

- ^ King, Critley (February 9, 2018). "Berea College endowment receives tax exemption". Richmond Register. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "About Our Labor Program- Berea College". Archived from the original on October 5, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ "Pay Schedule & Scale". Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ "Mountain Day". Forestry Outreach. January 30, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Labor Day". Berea Labor Program Office. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Berea College - Official Athletics Website". Berea College. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "DIII panel suggests consequences for not meeting conference requirements". NCAA.org. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ "Berea College and Pfeiffer University Set to Join USA South" (Press release). USA South Athletic Conference. May 4, 2016. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "USA South Announces Conference Restructuring" (Press release). USA South Athletic Conference. February 18, 2022. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "HCAC Welcomes Berea College as its Newest Member" (Press release). Heartland Collegiate Athletic Conference. June 1, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Herschbach, Dudley R.; Kolb, Charles E. (2014). "John Bennett Fenn" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "John B. Fenn - Autobiography". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on December 21, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ "HAMILTON, Finley | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ "Get to know bell hooks". Berea College. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Berea College (StudentsReview) - Comments, Reviews and Advice, Student Life at Berea College". StudentsReview. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Ellis, Normandi. (Spring 2007). Sam Hurst touches on a Few Great Ideas. Berea College Magazine. Berea College. Berea, KY. 77(4): 22–27.

- ^ The National Book Foundation's "5 Under 35" Fiction Selections for 2009 Archived 2010-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, National Book Foundation, accessed July 27, 2010

- ^ "The Sport of Kings by C. E. Morgan". www.publishersweekly.com. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "Rude Osolnik, a master wood "turner", dies at 86". New Bedford Standard-Times. AP Press. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "Obituaries". Lexington Herald-Leader. November 21, 2001. p. 18. Retrieved November 28, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Willie Parker, M.D. to Speak at Berea College Convocation". Berea College - First Interracial/Coeducational College in the South. November 7, 2016. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Biography for Jeffrey Reddick at IMDb

- ^ Hardin, John A. (1995). "Green Pinckney Russell of Kentucky Normal and Industrial Institute for Colored Persons". Journal of Black Studies. 25 (5): 610–621. doi:10.1177/002193479502500506. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2784634. S2CID 143448048.

- ^ Pegues, Albert Witherspoon (1892). "Rev. C. C. Stumm". Our Baptist Ministers and Schools. Willey & Company. pp. 472–481.

- ^ "Obituaries, Horace M. Trent". Physics Today. 18 (2): 86. 1965. doi:10.1063/1.3047224.

- ^ Writer, Crystal WylieRegister News (April 16, 2014). "Theater students hear actor, Berea alum Muse Watson". Richmond Register. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

Bibliography

- Adams, John D (2012). "The Berea College Mission to the Mountains: Teacher Training, The Normal Department, and Rural Community Development". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 110 (1): 33–66. doi:10.1353/khs.2012.0005. S2CID 154827109.

- Burnside, Jacqueline Grisby. "Philanthropists and politicians: A sociological profile of Berea College, 1855-1908" (PhD dissertation, Yale University) ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1988. 8917149.

- Harris, Adam (October 2018). "The Little College Where Tuition Is Free and Every Student Is Given a Job". The Atlantic.

- Lucas, Marion B. "Berea College in the 1870s and 1880s: Student Life at a Racially Integrated Kentucky College." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 98.1 (2000): 1–22. online

- Nelson, Paul David. "Experiment in interracial education at Berea College, 1858–1908." Journal of Negro History 59.1 (1974): 13–27.

- Peck, Elizabeth. Berea's First Century, 1855–1955. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1955.

- Wilson, Shannon H. Berea College: An Illustrated History. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006). ISBN 978-0-8131-2379-0 online