Hwasong-10

| Hwasong-10[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Intermediate-range ballistic missile |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | Successful test on 22 June 2016[1] |

| Used by | Korean People's Army Strategic Force, possibly Iran |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 12m |

| Diameter | 1.5m |

| Warhead |

|

| Warhead weight | 650–1,250 kg (est.)[2][3] |

| Engine | Liquid-propellant rocket (same or derived from R-27 R-29) |

| Propellant | Hypergolic combination of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) as fuel, and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) as oxidizer[4] |

Operational range | 3,000–4,000 km (est.)[2][5] |

Guidance system | Inertial guidance |

| Accuracy | 1,600 m Circular error probable[6] |

Launch platform | MAZ-based vehicle |

| Korean name | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 《화성-10》형 (무수단) |

|---|---|

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Hwaseong-10 |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hwasŏng-10 |

The Hwasong-10[a] (Korean: 《화성-10》형; Hancha: 火星 10型; lit. Mars Type 10) is a mobile intermediate-range ballistic missile developed by North Korea. Hwasong-10 was first revealed to the international community in a military parade on 10 October 2010 celebrating the Workers' Party of Korea's 65th anniversary, although experts believe these were mock-ups of the missile.[7][4] Hwasong-10 resembles the shape of the Soviet Union's R-27 Zyb submarine-launched missile, but is slightly longer.[4] It is based on the R-27, which uses a 4D10 engine propelled by unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO). These propellants are much more advanced than the kerosene compounds used in North Korea's Scuds and Hwasong-7 (Nodong) missiles.[6]

Since April 2016 the Hwasong-10 has been tested a number of times, with two apparent partial successes and a number of failures. The Hwasong-10 was not shown in the April 2017 and February 2018 military parades, suggesting that the design had not been deployed.[8][9]

Assuming a range of 3,200 km (2,000 mi), the Musudan could hit any target in East Asia (including US military bases in Guam and Okinawa).[10] The North Korean inventory of the missile is less than 50 launchers.[11]

Development

In the mid-1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, North Korea invited the Makeyev Design Bureau's ballistic missile designers and engineers to develop this missile, based on the R-27 Zyb. In 1992, a large contract between Korea Yon’gwang Trading Company and Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau of Miass, Russia was signed. The agreement stated that Russian engineers would go to the DPRK and assist in the development of the Zyb Space Launch Vehicle (SLV).[10]

It was decided that, as the Korean People's Army's MAZ-547A/MAZ-7916 Transporter erector launcher could carry 20 tonnes, and the R-27 Zyb was only 14.2 tonnes, the R-27 Zyb's fuel/oxidizer tank could be extended by approximately 2 metres.[4] Additionally, the warhead was reduced from a three-warhead MIRV to a single warhead.[citation needed]

The actual rocket design is a liquid fuel rocket, generally believed to use a hypergolic combination of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) as fuel, and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) as oxidizer.[4] Once the fuel/oxidizer combination are fed into the missile, it could maintain a 'ready to launch' condition for several days, or even weeks, like the R-27 SLBM, in moderate ambient temperatures. A fueled Hwasong-10 would not have the structural strength to be safely land transported, so would have to be fueled at the launch site.[4]

It was originally believed that the rocket motors of Hwasong-10 were the same as those within the second stage of the Taepodong-2, which North Korea unsuccessfully test fired in 2006.[12] However analysis of the Unha-3 launch, believed to be based on the Taepodong-2, showed that the second stage did not use the same fuel as the R-27, and is probably based on Hwasong-7 (Nodong) rocket technology.[4]

Before its test flight it was believed that there was a possibility that the Hwasong-10 would use the Nodong's kerosene and corrosion inhibited red fuming nitric acid (IRFNA) propellants, reducing the missile's range by about half.[4][13]

However it is unlikely that North Korea uses IRFNA propellants which would reduce its range by about half, after the experts acknowledged that the 22 June 2016 test could have had a range of 3,150 km if the missile was not launched in the lofted trajectory.[14]

Iranian Khorramshahr

North Korea sold a version of this missile to Iran under the designation BM-25. The number 25 represents the missile range (2500 km).[15][16][10][17] The Iranian designation is Khorramshahr, and it was unveiled and test-fired in September 2017.[18][19][20] Earlier test firing occurred in January 2017.[21] According to IISS expert Dempsey, the missile looks very similar to Hwasong-10.[22][23] It carries 1800 kg payload over 2000 km[24] (Iran claims it has decreased missile size over the initial version, thus reducing propellant mass and range).[25] Such a range covers targets not only in Israel, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, but even NATO members Romania, Bulgaria and Greece, if fired from Western Iran.[25] Iran claims it can carry multiple warheads, most likely a reference to submunitions.[26]

List of Hwasong-10 tests

| Attempt | Date | Location | Pre-launch announcement / detection | Outcome | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 April 2016 5:30 am Pyongyang Standard Time (PST) | Wonsan | Reports of the test is imminent surfaced on just a day before.[27] | Failure | Both United States and South Korea "detected and tracked" the missile followed by the confirmation of launch failure. South Korea further claims the missile in this test deviated from a "normal" trajectory.[28]

North Korea kept silent on the test despite the day is the 104th anniversary of the birthday of Kim Il Sung. |

| 2 | 28 April 2016 6:10 am PST | North Eastern Coast | None | Failure | Crashed a few seconds after liftoff. North Korea kept silent on the test.[29][30] |

| 3 | 28 April 2016 6:56 pm PST | Wonsan | None | Failure | According to United States sources, the missiles went an estimated 200 meters off the launchpad. North Korea kept silent on the test.[30] |

| 4 | 31 May 2016 5:20 am PST | Wonsan | None | Failure | Missile exploded on site. North Korea kept silent on the test.[31] |

| 5 | 22 June 2016 5:58 am PST | Wonsan | None | Success (North Korea) / Failure (South Korea & United States authorities) | Missile crashed at 150 km away from the site. First successful Hwasong-10 missile test that safely launched from the launch site but still exploded in the midway.[32][33] North Korea did not respond until after the 6th launch which hails the twin missile test was a success.

Although initial reports suggested that this test was a failure due to a relative short distance and the missile did explode in mid air, at least one US missile expert suggested otherwise. David Wright, a missile expert and co-director of the Union of Concerned Scientists' Global Security Program suggested that the North could have intentionally terminated its flight early to keep it from flying over Japan after launching it at a normal angle because the distance of flight at 150 km, corresponds roughly to burnout of the Hwasong-10 engines.[34] |

| 6 | 22 June 2016 5:58 am PST | Wonsan | None | Success (North Korea) / Partial Success (South Korea & United States) | South Korea, US and Japan eventually confirmed that the missile reached an apogee of about 1,000 km and landed in Sea of Japan (East Sea of Korea) at about 400 km away from the launch site. South Korea originally skeptical of the test as success because the missile did not reach a minimum of 500 km to be considered as an IRBM.

However, with the subsequent analysis, experts agreed that the about 1,000 km apogee is intended for the missile to fly at a steeper angle than would be ideal that could reach its maximum range of 3,500 km or more as a deliberate attempt to avoid Japanese airspace.[35] North Korea have hailed the twin test in 22 Jun 2016 as a 'complete success'in the state-owned TV channel KCNA with mentioning the missile accurately landed in the targeted waters 400 km away after flying to the maximum altitude of 1,413. 6 km along the planned flight orbit. North Korea confirms this missile as "Hwasong-10" The extract is re-uploaded in YouTube.[1] Kim Jong Un reiterate that "We have the sure capability to attack in an overall and practical way the Americans in the Pacific operation theatre.".[36] However, there are missile experts who are skeptical of Hwasong-10 being able to hit Guam with a 650 kg payload with the estimated range of 3,150 km. They have added that Hwasong-10 at this configuration will need to have their warhead reduced to below 500 kg in order to reach Guam, which is about slightly further than 3,400 km away from North Korea.[14] |

| 7 (Alleged) | 15 October 2016 12:03 pm PST | Kusong | None | Failure (South Korea & United States) | Intermediate Ballistic Missile launch failure detected by US military without elaborate details, which is believed to be a Hwasong-10 missile.[37][38] North Korea is silent on this report.

On 26 Oct 2016, Washington Post carried a report from an analysis from Jeffrey Lewis[b] who raised that there is 50% chance which the North Korea might have actually tested their domestic ICBM (Western intelligence sources named this missile as KN-08) based on the burn scars evidence taken from satellite imagery to be bigger than any other Musudan (Hwasong-10) tests. He concluded that this test has damaged the launch vehicle without flight.[39] In the same report, Jeffery Lewis has also stated not to place full trust on the U.S. agency StratCom for identifying missile. He had cited the track of StratCom which has misidentified the three missiles launched last month by identifying them initially as short-range Rodongs, subsequently medium-range Musudans which turned out to be extended-range Scud missiles.[39] The news is also reported by other media agencies, including Yonhap.[40][41] |

| 8 (Alleged) | 20 October 2016 7:00 am PST | Kusong | None | Failure (South Korea & United States) | Intermediate Ballistic Missile launch failure again detected by US military without elaborate details, which is again believed to be a Hwasong-10 missile.[42]

The launch just took place hours before the final US Presidential Election 2016 debates starts and the North Korea is silent on this report. On 26 Oct 2016, Washington Post carried a report from an analysis from Jeffrey Lewis[b] who raised that there is 50% chance which the North Korea might have actually tested their domestic ICBM (Western intelligence sources named this missile as KN-08) based on the burn scars evidence taken from satellite imagery to be bigger than any other Musudan (Hwasong-10) tests. However, the missile in 20 Oct 2016 test could have fly for a short distance before things went wrong as compared to the test in 15 October 2016 which damaged the launch vehicle instead.[39] In the same report, Jeffery Lewis has also stated not to place full trust on the U.S. agency StratCom for identifying missile. He had cited the track of StratCom which has misidentified the three missiles launched last month by identifying them initially as short-range Hwasong-7 (Rodong) missiles, subsequently medium-range Hwasong-10 (Musudan) missiles which turned out to be extended-range Scud missiles (Hwasong-9).[39] The news is also reported by other media agencies, including Yonhap.[40][41] |

Strategic implications

Currently, North Korea is also working on land based nuclear deterrents that are of Intercontinental range, such as Hwasong-13 (and its variant, named KN-14 under United States naming convention). It is also working a sea-based nuclear deterrent, such as Pukguksong-1 SLBM.

North Korea has confirmed to have successfully launched a Pukguksong-1 missile in a full test flight in a lofted trajectory and expecting Pukguksong-1 to be operationally deployed as early as before 2017 by South Korea military source on 25 August 2016.[43]

In May 2017, North Korea successfully tested a new missile, the Hwasong-12, with a similar range to the Hwasong-10. It had been displayed in the April 2017 military parade on the Hwasong-10 mobile launcher, and the Hwasong-12 may be intended to replace the Hwasong-10 which has been shown unreliable during its test programme.[44][8] The Hwasong-10 was not shown in the February 2018 military parade, suggesting again that the design had not been deployed.[9]

Description and technical specifications

- Launch weight: about 20 tons (est.)[4]

- Diameter: 1.5 m[4]

- Total Length: 12 m[4]

- Payload: 1,000–1,250 kg (est.)[2]

- Warhead: single

- Maximum range: 2,500–4,000 km (est.)[2]

- CEP: 1.3 km

- Launch platform: North Korean-produced TEL, resembling a stretched and modified MAZ-543

Operators

Current operators

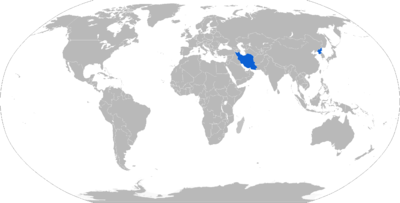

North Korea: According to one source, more than 200;[46] other source claims 12 deployed.[47] 16 were seen at once during the October 10, 2010 Military Parade, although experts contacted by the Washington Post believed these were mock-ups of the missile.[7]

North Korea: According to one source, more than 200;[46] other source claims 12 deployed.[47] 16 were seen at once during the October 10, 2010 Military Parade, although experts contacted by the Washington Post believed these were mock-ups of the missile.[7]

Suspected operators

Iran: 19, according to a leaked, classified U.S. State Department cable,[48] although Iran has not displayed the missiles until 2017 causing some U.S. intelligence officials to doubt the missiles were transferred to Iran.[7]

Iran: 19, according to a leaked, classified U.S. State Department cable,[48] although Iran has not displayed the missiles until 2017 causing some U.S. intelligence officials to doubt the missiles were transferred to Iran.[7]

Section 25 of this leaked cable (written before the 10 October 2010 appearance of the missile)[49] says:

Russia said that during its presentations in Moscow and its comments thus far during the current talks, the U.S. has discussed the BM-25 as an existing system. Russia questioned the basis for this assumption and asked for any facts the U.S. had to provide its existence such as launches, photos, etc. For Russia, the BM-25 is a mysterious missile. North Korea has not conducted any tests of this missile, but the U.S. has said that North Korea transferred 19 of these missiles to Iran. It is hard for Russia to follow the logic trail on this. Since Russia has not seen any evidence of this missile being developed or tested, it is hard for Russia to imagine that Iran would buy an untested system. Russia does not understand how a deal would be made for an untested missile. References to the missile's existence are more in the domain of political literature than technical fact. In short, for Russia, there is a question about the existence of this system.

Iran displayed the Khorramshahr missile 22 September 2017, claiming its range to be 2,000 km (1,200 mi).[50]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c KCTV (Kim Jong Un Guides Test-fire of Ballistic Rocket Hwasong-10) - YouTube, courtesy of KCNA

- ^ a b c d "Facts about North Korea's Musudan missile". AFP. GlobalPost. 8 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

IHS Jane's puts the estimated range at anywhere between 2,500 and 4,000 kilometres ... potential payload size has been put at 1.0-1.25 tonnes.

- ^ "Ракеты средней дальности КНДР | MilitaryRussia.Ru — отечественная военная техника (после 1945г.)". Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Markus Schiller (2012). Characterizing the North Korean Nuclear Missile Threat (Report). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-7621-2. TR-1268-TSF. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.nasic.af.mil/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=F2VLcKSmCTE%3d&portalid=19 [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b "Musudan (BM-25) - Missile Threat". Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b c John Pomfret and Walter Pincus (1 December 2010). "Experts question North Korea-Iran missile link from WikiLeaks document release". Washington Post. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b Panda, Ankit (15 May 2017). "North Korea's New Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile, the Hwasong-12: First Takeaways". The Diplomat. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ a b Elleman, Michael (8 February 2018). "North Korea's Army Day Military Parade: One New Missile System Unveiled". 38 North. U.S.-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b c https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/150325_Korea_Military_Balance.pdf[permanent dead link] [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat (Report). Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee. June 2017. p. 25. NASIC-1031-0985-17. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ "2nd 3rd Right Side". Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Markus Schiller, Robert H. Schmucker (31 May 2012). Explaining the Musudan (PDF) (Report). Schmucker Technologie. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ a b Michael Elleman: North Korea's Musudan missile effort advances Archived 2016-06-28 at the Wayback Machine - IISS Voices, 27 Jun 2016

- ^ "Janes | Latest defence and security news".

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (2017-02-02). "Iran's New Missile That Has Donald Trump Steaming Mad: Born in North Korea?". The National Interest. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Iran's Missile Test: Getting the Facts Straight on North Korea's Cooperation". 38 North. 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ^ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/iran-shows-khorramshahr-ballistic-missile-after-trump-s [dead link]

- ^ "Iran Unveils New Multiple Warhead Ballistic Missile". Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Iran ballistic missile Khorramshahr unveiled". 2017-09-22. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Iran Tests Khorramshahr Medium Range Ballistic Missile - Missile Threat". 31 January 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Trevithick, Joseph (23 September 2017). "Iran's New Ballistic Missile Looks a Lot Like a Modified North Korean One". Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Dempsey, Joseph. "Could #Iran Khorramshahr tapered end be consistent with distinct (submerged within fuel tank) Soviet 4D10 engine design used by #NorthKorea?pic.twitter.com/6zi2Q3ZtUO". Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Video of Iran's Successfull [sic] Test of New Long-Range Ballistic Missile". Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b Hilary Clarke; Shirzad Bozorgmehr (23 September 2017). "Iran tests new ballistic missile hours after showing it off". CNN. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Iran Displays Khorramshahr Missile - Missile Threat". 22 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Ahn, JH (14 Apr 2016) North Korea deploys missile for possible launch Archived 2017-02-28 at the Wayback Machine North Korea News, Retrieved 14 Apr 2016

- ^ North Korea's missile launch has failed, South's military says - Washingtonpost.com, 15 April 2016

- ^ South Korea: Suspected midrange North Korean missiles fail - Airforcetimes.com, 28 April 2016

- ^ a b North Korea launches two midrange missiles; both tests fail - CNN, 29 April 2016 GMT

- ^ Tamir Eshel (31 May 2016). "North Korean Musudan IRBM Failed - Again". Defense Update. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "(3rd LD) N. Korea botches fifth Musudan missile test-launch". Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "North Korean missiles fall in Sea of Japan- Pentagon". Reuters. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ N. Korea's fifth Musudan test might not have been failure: US expert - The Korea Times, 29 Jun 2016

- ^ North Korea's Musudan Missile Test Actually Succeeded. What Now? - The Diplomat, 23 Jun 2016

- ^ Kim Jong-un boasts of North Korea's Musudan missiles launch - International Business Times, 23 Jun 2016

- ^ North Korea conducted failed ballistic missile test, US military says - The Guardian, 15 Oct 2016 22:34 British Standard Time

- ^ US military detects 'failed ballistic missile launch' in North Korea after state media vows revenge for 'hostile acts' - The Independent, 15 Oct 2016

- ^ a b c d e Did North Korea just test missiles capable of hitting the U.S.? Maybe. - Washington Post, 26 Oct 2016

- ^ a b (LEAD) N. Korea's failed missile tests could have involved KN-08: U.S. expert, Yonhap 27 Oct 2016 12:06

- ^ a b 美专家:朝鲜本月试射的并非“舞水端”而是洲际弹道导弹 - CRI Online (In Chinese: "American Exert: North Korea's missile test in this month isn't 'Musudan' but an ICBM"), 27 Oct 2016 11:33:25

- ^ (LEAD) N. Korea's launch of Musudan missile ends in failure again: military - Yonhap, 20 Oct 2016 11:11

- ^ (2nd LD) N.K. leader calls SLBM launch success, boasts of nuke attack capacity - Yonhap, 25 Aug 2016 08:17am

- ^ Schilling, John (14 May 2017). "North Korea's Latest Missile Test: Advancing towards an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) While Avoiding US Military Action". 38 North. U.S.-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "How potent are North Korea's threats?". BBC News Online. 15 September 2015.

- ^ North's Missiles Raise Concerns, Radio Free Asia, 13 October 2010

- ^ North Korea Rolls Out Ballistic Missiles Archived 2010-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Global Security Newswire, 13 October 2010

- ^ William J. Broad; James Glanz; David E. Sanger (28 November 2010). "Iran Fortifies Its Arsenal With the Aid of North Korea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ U.S. Secretary of State (2010-02-24). "U.S.-Russia Joint Threat Assessment Talks - December 2009". 10STATE17263. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Ali Arouzi, NBC News (22 September 2017) Iran Shows Off Khorramshahr Ballistic Missile After Trump Speech

External links

- Missile Threat CSIS - Musudan (BM-25)

- R-27, astronautix.com

- R-27, Globalsecurity.org