Indian art

| History of art |

|---|

| Art forms of India |

|---|

|

Indian art consists of a variety of art forms, including painting, sculpture, pottery, and textile arts such as woven silk. Geographically, it spans the entire Indian subcontinent, including what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and at times eastern Afghanistan. A strong sense of design is characteristic of Indian art and can be observed in its modern and traditional forms.

The origin of Indian art can be traced to prehistoric settlements in the 3rd millennium BCE. On its way to modern times, Indian art has had cultural influences, as well as religious influences such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and Islam. In spite of this complex mixture of religious traditions, generally, the prevailing artistic style at any time and place has been shared by the major religious groups.

In historic art, sculpture in stone and metal, mainly religious, has survived the Indian climate better than other media and provides most of the best remains. Many of the most important ancient finds that are not in carved stone come from the surrounding, drier regions rather than India itself. Indian funeral and philosophic traditions exclude grave goods, which is the main source of ancient art in other cultures.

Indian artist styles historically followed Indian religions out of the subcontinent, having an especially large influence in Tibet, South East Asia and China. Indian art has itself received influences at times, especially from Central Asia and Iran, and Europe.

Early Indian art

Rock Art

Rock art of India includes rock relief carvings, engravings and paintings, some (but by no means all) from the South Asian Stone Age. It is estimated there are about 1300 rock art sites with over a quarter of a million figures and figurines.[1] The earliest rock carvings in India were discovered by Archibald Carlleyle, twelve years before the Cave of Altamira in Spain,[2] although his work only came to light much later via J Cockburn (1899).[3]

Dr. V. S. Wakankar discovered several painted rock shelters in Central India, situated around the Vindhya mountain range. Of these, the c. 750 sites making up the Bhimbetka rock shelters have been enrolled as a UNESCO World Heritage Site; the earliest paintings are some 10,000 years old.[4][5][6][7][8] The paintings in these sites commonly depicted scenes of human life alongside animals, and hunts with stone implements. Their style varied with region and age, but the most common characteristic was a red wash made using a powdered mineral called geru, which is a form of iron oxide (hematite).[9]

Indus Valley civilisation (c. 3300 BCE – c. 1750 BCE)

Despite its wide spread and sophistication, the Indus Valley civilisation seems to have taken no interest in public large-scale art, unlike many other early civilizations. A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some forms of dance. Additionally, the terracotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs.

By far the most common form of figurative art found is small carved seals. Thousands of steatite seals have been recovered, and their physical character is fairly consistent. In size they range from 3⁄4 inch to 11⁄2 inches square. In most cases they have a pierced boss at the back to accommodate a cord for handling or for use as personal adornment. Seals have been found at Mohenjo-Daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another, on the Pashupati Seal, sitting cross-legged in a yoga-like pose. This figure has been variously identified. Sir John Marshall identified a resemblance to the Hindu god, Shiva.[10]

The animal depicted on a majority of seals at sites of the mature period has not been clearly identified. Part bull, part zebra, with a majestic horn, it has been a source of speculation. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate claims that the image had religious or cultist significance, but the prevalence of the image raises the question of whether or not the animals in images of the IVC are religious symbols.[11] The most famous piece is the bronze Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-Daro, which shows remarkably advanced modelling of the human figure for this early date.[12]

After the end of the Indus Valley Civilization, there is a surprising absence of art of any great degree of sophistication until the Buddhist era. It is thought that this partly reflects the use of perishable organic materials such as wood.[13]

Vedic period

The millennium following the collapse of the Indus Valley civilisation, coinciding with the Indo-Aryan migration during the Vedic period, is devoid of anthropomorphical depictions.[14] It has been suggested that the early Vedic religion focused exclusively on the worship of purely "elementary forces of nature by means of elaborate sacrifices", which did not lend themselves easily to anthropomorphological representations.[15][16] Various artefacts may belong to the Copper Hoard culture (2nd millennium BCE), some of them suggesting anthropomorphological characteristics.[17] Interpretations vary as to the exact signification of these artifacts, or even the culture and the periodization to which they belonged.[17] Some examples of artistic expression also appear in abstract pottery designs during the Black and red ware culture (1450-1200 BCE) or the Painted Grey Ware culture (1200-600 BCE), with finds in a wide area, including the area of Mathura.[17]

After a gap of about a thousand years, most of the early finds correspond to what is called the "second period of urbanization" in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE.[17] The anthropomorphic depiction of various deities apparently started in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, possibly as a consequence of the influx of foreign stimuli initiated with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, and the rise of alternative local faiths challenging Vedism, such as Buddhism, Jainism and local popular cults.[14]

Mauryan art (c. 322 BCE – c. 185 BCE)

The north Indian Maurya Empire flourished from 322 BCE to 185 BCE, and at its maximum extent controlled all of the sub-continent except the extreme south as well as influences from Indian ancient traditions, and Ancient Persia,[18] as shown by the Pataliputra capital.

The emperor Ashoka, who died in 232 BCE, adopted Buddhism about half-way through his 40-year reign, and patronized several large stupas at key sites from the life of the Buddha, although very little decoration from the Mauryan period survives, and there may not have been much in the first place. There is more from various early sites of Indian rock-cut architecture.

The most famous survivals are the large animals surmounting several of the Pillars of Ashoka, which showed a confident and boldly mature style and craft and first of its kind iron casting without rust until date, which was in use by vedic people in rural areas of the country, though we have very few remains showing its development.[19] The famous detached Lion Capital of Ashoka, with four animals, was adopted as the official Emblem of India after Indian independence.[20] Mauryan sculpture and architecture is characterized by a very fine Mauryan polish given to the stone, which is rarely found in later periods.

Many small popular terracotta figurines are recovered in archaeology, in a range of often vigorous if somewhat crude styles. Both animals and human figures, usually females presumed to be deities, are found.[21]

Colossal Yaksha statuary (2nd century BCE)

Yakshas seem to have been the object of an important cult in the early periods of Indian history, many of them being known such as Kubera, king of the Yakshas, Manibhadra or Mudgarpani.[23] The Yakshas are a broad class of nature-spirits, usually benevolent, but sometimes mischievous or capricious, connected with water, fertility, trees, the forest, treasure and wilderness,[24][25] and were the object of popular worship.[26] Many of them were later incorporated into Buddhism, Jainism or Hinduism.[23]

In the 2nd century BCE, Yakshas became the focus of the creation of colossal cultic images, typically around 2 meters or more in height, which are considered as probably the first Indian anthropomorphic productions in stone.[27][23] Although few ancient Yaksha statues remain in good condition, the vigor of the style has been applauded, and expresses essentially Indian qualities.[27] They are often pot-bellied, two-armed and fierce-looking.[23] The Yakshas are often depicted with weapons or attributes, such as the Yaksha Mudgarpani who in the right hand holds a mudgar mace, and in the left hand the figure of a small standing devotee or child joining hands in prayer.[28][23] It is often suggested that the style of the colossal Yaksha statuary had an important influence on the creation of later divine images and human figures in India.[29] The female equivalent of the Yakshas were the Yakshinis, often associated with trees and children, and whose voluptuous figures became omnipresent in Indian art.[23]

Some Hellenistic influence, such as the geometrical folds of the drapery or the walking stance of the statues, has been suggested.[27] According to John Boardman, the hem of the dress in the monumental early Yaksha statues is derived from Greek art.[27] Describing the drapery of one of these statues, John Boardman writes: "It has no local antecedents and looks most like a Greek Late Archaic mannerism", and suggests it is possibly derived from the Hellenistic art of nearby Bactria where this design is known.[27]

In the production of colossal Yaksha statues carved in the round, which can be found in several locations in northern India, the art of Mathura is considered as the most advanced in quality and quantity during this period.[30]

Buddhist art (c. 150 BCE – c. 500 CE)

The major survivals of Buddhist art begin in the period after the Mauryans, from which good quantities of sculpture survives. Some key sites are Sanchi, Bharhut and Amaravati, some of which remain in situ, with others in museums in India or around the world. Stupas were surrounded by ceremonial fences with four profusely carved toranas or ornamental gateways facing the cardinal directions. These are in stone, though clearly adopting forms developed in wood. They and the walls of the stupa itself can be heavily decorated with reliefs, mostly illustrating the lives of the Buddha. Gradually life-size figures were sculpted, initially in deep relief, but then free-standing.[32]

Mathura was the most important centre in this development, which applied to Hindu and Jain art as well as Buddhist.[33] The facades and interiors of rock-cut chaitya prayer halls and monastic viharas have survived better than similar free-standing structures elsewhere, which were for long mostly in wood. The caves at Ajanta, Karle, Bhaja and elsewhere contain early sculpture, often outnumbered by later works such as iconic figures of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, which are not found before 100 CE at the least.

Buddhism developed an increasing emphasis on statues of the Buddha, which was greatly influenced by Hindu and Jain religious figurative art, The figures of this period which were also influenced by the Greco-Buddhist art of the centuries after the conquests of Alexander the Great. This fusion developed in the far north-west of India, especially Gandhara in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan.[34] The Indian Kushan Empire spread from Central Asia to include northern India in the early centuries CE, and briefly commissioned large statues that were portraits of the royal dynasty.[35]

Shunga Dynasty (c. 185 BCE – 72 BCE)

With the fall of the Maurya Empire, control of India was returned to the older custom of regional dynasties, one of the most significant of which was the Shunga Dynasty (c. 185 BCE – 72 BCE) of central India. During this period, as well as during the Satavahana Dynasty which occurred concurrently with the Shunga Dynasty in south India, some of the most significant early Buddhist architecture was created. Arguably, the most significant architecture of this dynasty is the stupa, a religious monument which usually holds a sacred relic of Buddhism. These relics were often, but not always, in some way directly connected to the Buddha. Due to the fact that these stupas contained remains of the Buddha himself, each stupa was venerated as being an extension of the Buddha's body, his enlightenment, and of his achievement of nirvana. The way in which Buddhists venerate the stupa is by walking around it in a clockwise manner.[36]

One of the most notable examples of the Buddhist stupa from the Shunga Dynasty is The Great Stupa at Sanchi, which was thought to be founded by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka c. 273 BCE – 232 BCE during the Maurya Empire.[37] The Great Stupa was enlarged to its present diameter of 120 feet, covered with a stone casing, topped with a balcony and umbrella, and encircled with a stone railing during the Shunga Dynasty c. 150 BCE – 50 BCE.

In addition to architecture, another significant art form of the Shunga Dynasty is the elaborately moulded terracotta plaques. As seen in previous examples from the Mauryan Empire, a style in which surface detail, nudity, and sensuality is continued in the terracotta plaques of the Shunga Dynasty. The most common figural representations seen on these plaques are women, some of which are thought to be goddesses, who are mostly shown as bare-chested and wearing elaborate headdresses.[38]

Satavahana dynasty (c. 1st/3rd century BCE – c. 3rd century CE)

The Satavahana dynasty ruled in central India, and sponsored many large Buddhist monuments, stupas, temples, and prayer-halls, including the Amaravati Stupa, the Karla Caves, and the first phase of the Ajanta Caves.[39]

Stupas are religious monuments built on burial mounds, which contain relics beneath a solid dome. Stupas in different areas of India may vary in structure, size, and design; however, their representational meanings are quite similar. They are designed based on a mandala, a graph of cosmos specific to Buddhism. A traditional stupa has a railing that provides a sacred path for Buddhist followers to practice devotional circumambulation in ritual settings. Also, ancient Indians considered caves as sacred places since they were inhabited by holy men and monks. A chaitya was constructed from a cave.[36]

Relief sculptures of Buddhist figures and epigraphs written in Brahmi characters are often found in divine places specific to Buddhism.[40] To celebrate the divine, Satavahana people also made stone images as the decoration in Buddhist architectures. Based on the knowledge of geometry and geology, they created ideal images using a set of complex techniques and tools such as chisels, hammers, and compasses with iron points.[41]

In addition, delicate Satavahana coins show the capacity of creating art in that period. The Satavahanas issued coins primarily in copper, lead and potin. Later on, silver came into use when producing coins. The coins usually have detailed portraits of rulers and inscriptions written in the language of Tamil and Telugu.[40]

Kushan Empire (c. 30 CE – c. 375 CE)

Officially established by Kujula Kadphises, the first Kushan emperor who united the Yuezhi tribes, the Kushan empire was a syncretic empire in central and southern Asia, including the regions of Gandhara and Mathura in northern India. From 127 to 151 CE, Gandharan reached its peak under the reign of Kanishka the Great. In this period, Kushan art inherited the Greco-Buddhist art.[42] Mahayana Buddhism flourished, and the depictions of Buddha as a human form first appeared in art. Wearing a monk's robe and a long length of cloth draped over the left shoulder and around the body, the Buddha was depicted with 32 major lakshanas (distinguishing marks), including a golden-colored body, an ushnisha (a protuberance) on the top of his head, heavy earrings, elongated earlobes, long arms, the impression of a chakra (wheel) on the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet, and the urna (a mark between his eyebrows).[36]

One of the hallmarks of Gandharan art is its relation to naturalism of Hellenistic art. The naturalistic features found in Gandharan sculptures include the three-dimensional treatment of the drapery, with unregularized folds that are in realistic patterns of random shape and thickness. The physical form of the Buddha and his bodhisattvas are well-defined, solid, and muscular, with swelling chests, arms, and abdomens.[43] Buddhism and Buddhism art spread to Central Asia and the far East across Bactria and Sogdia, where the Kushan Empire met the Han Dynasty of China.[44]

Gupta art (c. 320 CE – c. 550 CE)

The Gupta period is generally regarded as a classic peak of north Indian art for all the major religious groups. Although painting was evidently widespread, and survives in the Ajanta Caves, the surviving works are almost all religious sculpture.

The period saw the emergence of the iconic carved stone deity in Hindu art, as well as the Buddha-figure and Jain tirthankara figures, these last often on a very large scale. The main centres of sculpture were Mathura Sarnath, and Gandhara, the last the centre of Greco-Buddhist art.

The Gupta period marked the "golden age" of classical Hinduism,[45] and saw the earliest constructed Hindu temple architecture, though survivals are not numerous.

- Seated Buddha, 5th century CE, Sarnath Museum

- Iron Pillar of Delhi known for its rust-resistant composition of metals, c. 3rd–4th century CE

- Ajanta Caves Fresco

Middle kingdoms and the Early Medieval period (c. 600 CE – c. 1206 CE/1526 CE)

Over this period Hindu temple architecture matured into a number of regional styles, and a large proportion of the art historical record for this period consists of temple sculpture, much of which remains in place. The political history of the middle kingdoms of India saw India divided into many states, and since much of the grandest building was commissioned by rulers and their court, this helped the development of regional differences. Painting, both on a large scale on walls, and in miniature forms, was no doubt very widely practiced, but survivals are rare. Medieval bronzes have most commonly survived from either the Tamil south, or the Himalayan foothills.

Dynasties of South India (c. 3rd century CE – c. 1200 CE)

Inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka mention coexistence of the northern kingdoms with the triumvirate of Chola, Chera and Pandya Tamil dynasties, situated south of the Vindhya mountains.[46] The medieval period witnessed the rise and fall of these kingdoms, in conjunction with other kingdoms in the area. It is during the decline and resurgence of these kingdoms that Hinduism was renewed. It fostered the construction of numerous temples and sculptures.

- Youth in lotus pond, ceiling fresco at Sittanvasal, 850 CE

The Shore Temple at Mamallapuram constructed by the Pallavas symbolizes early Hindu architecture, with its monolithic rock relief and sculptures of Hindu deities. They were succeeded by Chola rulers who were prolific in their pursuit of the arts. The Great Living Chola Temples of this period are known for their maturity, grandeur and attention to detail, and have been recognized as a UNESCO Heritage Site.[47] The Chola period is also known for its bronze sculptures, the lost-wax casting technique and fresco paintings. Thanks to the Hindu kings of the Chalukya dynasty, Jainism flourished alongside Islam evidenced by the fourth of the Badami cave temples being Jain instead of Vedic. The kingdoms of South India continued to rule their lands until the Muslim invasions that established sultanates there and destroyed much of the temples and marvel examples of architectures and sculptures

Other Hindu states are now mainly known through their surviving temples and their attached sculpture. These include Badami Chalukya architecture (5th to 6th centuries), Western Chalukya architecture (11th to 12th centuries) and Hoysala architecture (11th to 14th centuries), all centred on modern Karnataka.

Eastern India

In east India, Odisha and West Bengal, Kalinga architecture was the broad temple style, with local variants, before the Muslim conquest.

In antiquity, Bengal was a pioneer of painting in Asia under the Pala Empire. Miniature and scroll painting flourished during the Mughal Empire. Kalighat painting or Kalighat Pat originated in the 19th century Bengal, in the vicinity of Kalighat Kali Temple of Kolkata, and from being items of souvenir taken by the visitors to the Kali temple, the paintings over a period of time developed as a distinct school of Indian painting. From the depiction of Hindu gods other mythological characters, the Kalighat paintings developed to reflect a variety of themes.

- Rasmancha, Bishnupur. Built by King Bir Hambir, the temple has an unusual elongated pyramidical tower, surrounded by hut-shaped turrets, which were very typical of Bengali roof structures of the time.

- Wooden Owls of Natungram, West Bengal, India. The wooden owl is an integral part of an ancient and indigenous tradition and art form in Bengal.

late Medieval Period and Colonial Era (c. 1526 CE – c. 1757 CE)

Mughal art

Although Islamic conquests in India were made as early as the first half of the 10th century, it wasn't until the Mughal Empire that one observes emperors with a patronage for the fine arts. Emperor Humayun, during his reestablishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1555, brought with him Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad, two of the finest painters from Persian Shah Tahmasp's renowned atelier.

During the reign of Akbar (1556–1605), the number of painters grew from around 30 during the creation of the Hamzanama in the mid-1560s, to around 130 by the mid-1590s.[48] According to court historian Abu'l-Fazal, Akbar was hands-on in his interest of the arts, inspecting his painters regularly and rewarding the best.[49] It is during this time that Persian artists were attracted to bringing their unique style to the empire. Indian elements were present in their works from the beginning, with the incorporation of local Indian flora and fauna that were otherwise absent from the traditional Persian style. The paintings of this time reflected the vibrancy and inclusion of Akbar's kingdom, with production of Persian miniatures, the Rajput paintings (including the Kangra school) and the Pahari style of Northern India. They also influenced the Company style watercolor paintings created during the British rule many years later.

- Jama Masjid, Delhi, Willam Carpenter, 1852. Watercolor.

With the death of Akbar, his son Jahangir (1605–1627) took the throne. He preferred each painter work on a single piece rather than the collaboration fostered during Akbar's time. This period marks the emergence of distinct individual styles, notably Bishan Das, Manohar Das, Abu al-Hasan, Govardhan, and Daulat.[50] Jahangir himself had the capability to identify the work of each individual artist, even if the work was unnamed. The Razmnama (Persian translation of the Hindu epic Mahabharata) and an illustrated memoir of Jahangir, named Tuzuk-i Jahangiri, were created under his rule. Jahangir was succeeded by Shah Jahan (1628–1658), whose most notable architectural contribution is the Taj Mahal. Paintings under his rule were more formal, featuring court scenes, in contrast to the personal styles from his predecessor's time. Aurangzeb (1658–1707), who held increasingly orthodox Sunni beliefs, forcibly took the throne from his father Shah Jahan. With a ban of music and painting in 1680, his reign saw the decline of Mughal patronage of the arts.

As painting declined in the imperial court, artists and the general influence of Mughal painting spread to the princely courts and cities of north India, where both portraiture, the illustration of the Indian epics, and Hindu religious painting developed in many local schools and styles. Notable among these were the schools of Rajput, Pahari, Deccan, Kangra painting.

- Jahangir in Darbar, from the Jahangir-nama, c. 1620. Gouache on paper.

- Portrait of the emperor Shah Jahan, enthroned. ca. 17th century.

- A durbar scene with the newly crowned Emperor Aurangzeb.

Other medieval Indian kingdoms

The last empire in southern India has left spectacular remains of Vijayanagara architecture, especially at Hampi, Karnataka, often heavily decorated with sculpture. These developed the Chola tradition. After the Mughal conquest, the temple tradition continued to develop, mainly in the expansion of existing temples, which added new outer walls with increasingly large gopurams, often dwarfing the older buildings in the centre. These became usually thickly covered with plaster statues of deities and other religious figures, which need have their brightly coloured paint kept renewed at intervals so they do not erode away.

In South-Central India, during the late fifteenth century after the Middle kingdoms, the Bahmani sultanate disintegrated into the Deccan sultanates centered at Bijapur, Golconda, Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Berar. They used vedic techniques of metal casting, stone carving, and painting, as well as a distinctive architectural style with the addition of citadels and tombs from Mughal architecture. For instance, the Baridi dynasty (1504–1619) of Bidar saw the invention of bidri ware, which was adopted from Vedic and Maurya period ashoka pillars of zinc mixed with copper, tin, and lead and inlaid with silver or brass, then covered with a mud paste containing sal ammoniac, which turned the base metal black, highlighting the colour and sheen of the inlaid metal. Only after the Mughal conquest of Ahmadnagar in 1600 did the Persian influence patronized by the Turco-Mongol Mughals begin to affect Deccan art.

- Bidriware water-pipe base, c. 18th century. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Portrait of Abu'l Hasan, the last Sultan of Golconda, c. late 17th—early 18th century

- Chand Bibi hawking, an 18th-century Deccan painting, gouache heightened with gold on paper

British period (1857–1947)

British colonial rule had a great impact on Indian art, especially from the mid-19th century onwards. Many old patrons of art became less wealthy and influential, and Western art more ubiquitous as the British Empire established schools of art in major cities. The oldest, the Government College of Fine Arts, Chennai, was established in 1850. In major cities with many Europeans, the Company style of small paintings became common, created by Indian artists working for European patrons of the East India Company. The style mainly used watercolour, to convey soft textures and tones, in a style combining influences from Western prints and Mughal painting.[51] By 1858, the British government took over the task of administration of India under the British Raj. Many commissions by Indian princes were now wholly or partly in Western styles, or the hybrid Indo-Saracenic architecture. The fusion of Indian traditions with European style at this time is evident from Raja Ravi Varma's oil paintings of sari-clad women in a graceful manner.

- Company painting by Dip Chand (c. 1760 – c. 1764) depicting an official of the East India Company, perhaps William Fullerton of Rosemount, surgeon and mayor of Calcutta in 1757

- Tipu's Tiger, an 18th-century automata with its keyboard visible. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

- Shakuntala by Raja Ravi Varma (1870). Oil on canvas.

- Asoka's Queen by Abanindranath Tagore (c. 1910). Chromoxylograph.

Bengal School of Art

The Bengal School of Art commonly referred as Bengal School, was an art movement and a style of Indian painting that originated in Bengal, primarily Kolkata and Shantiniketan, and flourished throughout the Indian subcontinent, during the British Raj in the early 20th century. Also known as 'Indian style of painting' in its early days, it was associated with Indian nationalism (swadeshi) and led by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951), but was also promoted and supported by British arts administrators like E. B. Havell, the principal of the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata from 1896; eventually it led to the development of the modern Indian painting.

Tagore later attempted to develop links with Japanese artists as part of an aspiration to construct a pan-Asianist model of art. Through the paintings of 'Bharat Mata', Abanindranath established the pattern of patriotism. Painters and artists of Bengal school were Nandalal Bose, M.A.R Chughtai, Sunayani Devi (sister of Abanindranath Tagore), Manishi Dey, Mukul Dey, Kalipada Ghoshal, Asit Kumar Haldar, Sudhir Khastgir, Kshitindranath Majumdar, Sughra Rababi, Sukhvir Sanghal.[52]

Between 1920 and 1925, Gaganendranath pioneered experiments in modernist painting. Partha Mitter describes him as "the only Indian painter before the 1940s who made use of the language and syntax of Cubism in his painting". From 1925 onwards, the artist developed a complex post-cubist style.

With the Swadeshi Movement gaining momentum by 1905, Indian artists attempted to resuscitate pre-colonial Indian cultural identities, rejecting the Romanticized style of the Company paintings and the mannered work of Raja Ravi Varma and his followers. Thus was created what is known today as the Bengal School of Art, led by the reworked Asian styles (with an emphasis on Indian nationalism) of Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951), who has been referred to as the father of Modern Indian art.[53] Other artists of the Tagore family, such as Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) and Gaganendranath Tagore (1867–1938) as well as new artists of the early 20th century such as Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941) were responsible for introducing Avant-garde western styles into Indian Art. Many other artists like Jamini Roy and later S.H. Raza took inspiration from folk traditions. In 1944, K.C.S. Paniker founded the Progressive Painters' Association (PPA) thus giving rise to the "madras movement" in art.[54]

- Bharat Mata by Abanindranath Tagore.

- Journey's End by Abanindranath Tagore.

- Two cats holding a large prawn by Jamini Roy.

- Pratima Visarjan by Gaganendranath Tagore.

- Gaganendranath Tagore – Meeting at the Staircase.

- Fresco by Nandalal Bose in Dinantika – Ashram Complex – Santiniketan.

Contemporary art (c. 1900 CE-present)

In 1947, India became independent of British rule. A group of six artists – K. H. Ara, S. K. Bakre, H. A. Gade, M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza and Francis Newton Souza – founded the Bombay Progressive Artists' Group in the year 1952, to establish new ways of expressing India in the post-colonial era. Though the group was dissolved in 1956, it was profoundly influential in changing the idiom of Indian art. Almost all India's major artists in the 1950s were associated with the group. Some of those who are well-known today are Bal Chabda, Manishi Dey, V. S. Gaitonde, Krishen Khanna, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, K. G. Subramanyan, A. Ramachandran, Devender Singh, Akbar Padamsee, John Wilkins, Himmat Shah and Manjit Bawa.[55] Present-day Indian art is varied as it had been never before. Among the best-known artists of the newer generation include Bose Krishnamachari and Bikash Bhattacharjee.

Painting and sculpture remained important in the later half of the twentieth century, though in the work of leading artists such as Nalini Malani, Subodh Gupta, Narayanan Ramachandran, Vivan Sundaram, Jitish Kallat, GR Iranna, Bharati Kher, Chittravanu Muzumdar, they often found radical new directions. Bharti Dayal has chosen to handle the traditional Mithila painting in most contemporary way and created her own style through the exercises of her own imagination, they appear fresh and unusual.

The increase in discourse about Indian art, in English as well as vernacular Indian languages, changed the way art was perceived in the art schools. Critical approach became rigorous; critics like Geeta Kapur, R. Siva Kumar,[56][57] Shivaji K. Panikkar, Ranjit Hoskote, amongst others, contributed to re-thinking contemporary art practice in India.

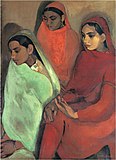

- Group of Three Girls by Amrita Sher-Gil

- Boating by Jamini Roy.

- Pseudorealistic Indian painting. Couple, Kids and Confusion. by Devajyoti Ray.

- Mural by Satish Gujral.

By materials and art forms

Sculpture

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilisation (3300–1700 BC), found in sites at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan. These include the famous small bronze male dancerNataraja. However such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered by pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted. After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[58]

The great tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to begin relatively late, with the reign of Ashoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, mostly lions, of which six survive.[59] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood.[60] Indeed, wood continued to be the main sculptural and architectural medium in Kerala throughout all historic periods until recent decades.[61]

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE in far northern India, in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara from what is now southern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, sculptures became more explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha's life and teachings. Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human form before this time, but only through some of his symbols. This may be because Gandharan Buddhist sculpture in modern Afghanistan displays Greek and Persian artistic influence. Artistically, the Gandharan school of sculpture is said to have contributed wavy hair, drapery covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, acanthus leaf decorations, etc.

The pink sandstone Hindu, Jain and Buddhist sculptures of Mathura from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE reflected both native Indian traditions and the Western influences received through the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and effectively established the basis for subsequent Indian religious sculpture.[60] The style was developed and diffused through most of India under the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550) which remains a "classical" period for Indian sculpture, covering the earlier Ellora Caves,[62] though the Elephanta Caves are probably slightly later.[63] Later large scale sculpture remains almost exclusively religious, and generally rather conservative, often reverting to simple frontal standing poses for deities, though the attendant spirits such as apsaras and yakshi often have sensuously curving poses. Carving is often highly detailed, with an intricate backing behind the main figure in high relief. The celebrated lost wax bronzes of the Chola dynasty (c. 850–1250) from south India, many designed to be carried in processions, include the iconic form of Shiva as Nataraja,[64] with the massive granite carvings of Mahabalipuram dating from the previous Pallava dynasty.[65] The Chola period is also remarkable for its sculptures and bronzes.[66] Among the existing specimens in the various museums of the world and in the temples of South India may be seen many fine figures of Siva in various forms, Vishnu and his wife Lakshmi, Siva saints and many more.[67]

Wall painting

The tradition and methods of Indian cliff painting gradually evolved throughout many thousands of years – there are multiple locations found with prehistoric art. The early caves included overhanging rock decorated with rock-cut art and the use of natural caves during the Mesolithic period (6000 BCE). Their use has continued in some areas into historic times.[68] The Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka are on the edge of the Deccan Plateau where deep erosion has left huge sandstone outcrops. The many caves and grottos found there contain primitive tools and decorative rock paintings that reflect the ancient tradition of human interaction with their landscape, an interaction that continues to this day.[69]

The oldest surviving frescoes of the historical period have been preserved in the Ajanta Caves with Cave 10 having some from the 1st century CE, though the larger and more famous groups are from the 5th century. Despite climatic conditions that tend to work against the survival of older paintings, in total there are known more than 20 locations in India with paintings and traces of former paintings of ancient and early medieval times (up to the 8th to 10th centuries CE),[70] although these are just a tiny fraction of what would have once existed. The most significant frescoes of the ancient and early medieval period are found in the Ajanta, Bagh, Ellora, and Sittanavasal caves, the last being Jain of the 7th-10th centuries. Although many show evidence of being by artists mainly used to decorating palaces, no early secular wall-paintings survive.[71]

The Chola fresco paintings were discovered in 1931 within the circumambulatory passage of the Brihadisvara Temple at Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, and are the first Chola specimens discovered. Researchers have discovered the technique used in these frescoes. A smooth batter of limestone mixture is applied over the stones, which took two to three days to set. Within that short span, such large paintings were painted with natural organic pigments. During the Nayak period the Chola paintings were painted over. The Chola frescoes lying underneath have an ardent spirit of saivism is expressed in them. They probably synchronised with the completion of the temple by Rajaraja Cholan the Great.

Kerala mural painting has well-preserved fresco or mural or wall painting in temple walls in Pundarikapuram, Ettumanoor and Aymanam and elsewhere.

Miniature painting

Although few Indian miniatures survive from before about 1000 CE, and some from the next few centuries, there was probably a considerable tradition. Those that survive are initially illustrations for Buddhist texts, later followed by Jain and Hindu equivalents, and the decline of Buddhist as well as the vulnerable support material of the palm-leaf manuscript probably explain the rarity of early examples.[72]

Mughal painting in miniatures on paper developed very quickly in the late 16th century from the combined influence of the existing miniature tradition and artists trained in the Persian miniature tradition imported by the Mughal Emperor's court. New ingredients in the style were much greater realism, especially in portraits, and an interest in animals, plants and other aspects of the physical world.[73] Deccan painting developed around the same time in the Deccan sultanates courts to the south, in some ways more vital, if less poised and elegant.[74]

Miniatures either illustrated books or were single works for muraqqas or albums of painting and Islamic calligraphy. The style gradually spread in the next two centuries to influence painting on paper in both Muslim and Hindu princely courts, developing into a number of regional styles often called "sub-Mughal", including Rajput painting, Pahari painting, and finally Company painting, a hybrid watercolour style influenced by European art and largely patronized by the people of the British raj. In "pahari" ("mountain") centres like that of Kangra painting the style remained vital and continued to develop into the early decades of the 19th century.[75] From the mid-19th century Western-style easel paintings became increasingly painted by Indian artists trained in Government art schools.

Jewellery

The Indian subcontinent has the longest continuous legacy of jewellery-making, with a history of over 5,000 years.[76] Using jewellery as a store of capital remains more common in India than in most modern societies, and gold appears always to have been strongly preferred for the metal. India and the surrounding areas were important sources of high-quality gemstones, and the jewellery of the ruling class is typified by using them lavishly. One of the first to start jewellery-making were the people of the Indus Valley civilization. Early remains are few, as they were not buried with their owners.

Other materials

Wood was undoubtedly extremely important, but rarely survives long in the Indian climate. Organic animal materials such as ivory or bone were discouraged by the Dharmic religions, although Buddhist examples exist, such as the Begram ivories, many of Indian manufacture, but found in Afghanistan, and some relatively modern carved tusks. In Muslim settings they are more common.

Temple art

Obscurity shrouds the period between the decline of the Harappans and the definite historic period starting with the Mauryas, and in the historical period, the earliest Indian religion to inspire major artistic monuments was Buddhism. Though there may have been earlier structures in wood that have been transformed into stone structures, there are no physical evidences for these except textual references. Soon after the Buddhists initiated rock-cut caves, Hindus and Jains started to imitate them at Badami, Aihole, Ellora, Salsette, Elephanta, Aurangabad and Mamallapuram and Mughals. It appears to be a constant in Indian art that the different religions shared a very similar artistic style at any particular period and place, though naturally adapting the iconography to match the religion commissioning them.[77] Probably the same groups of artists worked for the different religions regardless of their own affiliations.

Buddhist art first developed during the Gandhara period and Amaravati periods around the 1st century BCE. It continued to flourish during the Gupta Periods and Pala periods that comprise the Golden Age of India, even as rulers became mostly Hindu.[78] Buddhist art largely disappeared by the end of the first millennium, after which Hindu dynasties like the Pallava, Chola, Hoysala and Vijayanagara Empires developed their own styles.

There is no time line that divides the creation of rock-cut temples and free-standing temples built with cut stone as they developed in parallel. The building of free-standing structures began in the 5th century, while rock-cut temples continued to be excavated until the 12th century. An example of a free-standing structural temple is the Shore Temple, a part of the Mahabalipuram World Heritage Site, with its slender tower, built on the shore of the Bay of Bengal with finely carved granite rocks cut like bricks and dating from the 8th century.[79][80]

Folk and tribal art

Folk and tribal art in India takes on different manifestations through varied media such as pottery, painting, metalwork,[81] paper-art, weaving and designing of objects such as jewellery and toys. These are not just aesthetic objects but in fact have an important significance in people's lives and are tied to their beliefs and rituals. The objects can range from sculpture, masks (used in rituals and ceremonies), paintings, textiles, baskets, kitchen objects, arms and weapons, and the human body itself (tattoos and piercings). There is a deep symbolic meaning that is attached to not only the objects themselves but also the materials and techniques used to produce them.

Often puranic gods and legends are transformed into contemporary forms and familiar images. Fairs, festivals, local heroes (mostly warriors) and local deities play a vital role in these arts (Example: Nakashi art from Telangana or Cherial Scroll Painting).

Folk art also includes the visual expressions of the wandering nomads. This is the art of people who are exposed to changing landscapes as they travel over the valleys and highlands of India. They carry with them the experiences and memories of different spaces and their art consists of the transient and dynamic pattern of life. The rural, tribal and arts of the nomads constitute the matrix of folk expression. Examples of folk arts are:

- Warli Painting - The Warli region of Maharashtra had the tribal art form known as "Warli painting" first appear. The art genre uses straightforward geometric patterns and shapes to produce images of everyday life, the natural world, and religious themes. The paintings are often created in white on a background of red or ochre.[82]

- Madhubani Painting: Folk art, known as "Madhubani painting", has its roots in the Mithila area of Bihar. The paintings incorporate sophisticated geometric patterns frequently and depict images of deities, nature, and everyday life in vivid colors.[83]

- Gond Painting: The Gond region of Madhya Pradesh had the tribal art form known as "Gond painting" first appear. The elaborate patterns and designs of the art form are frequently influenced by nature and the spiritual practices of the Gond people. The paintings are typically done in bright colors and feature bold, graphic lines.[84]

While most tribes and traditional folk artist communities are assimilated into the familiar kind of civilized life, they still continue to practice their art. Unfortunately though, market and economic forces have ensured that the numbers of these artists are dwindling.[85][86] A lot of effort is being made by various NGOs and the Government of India to preserve and protect these arts and to promote them. Several scholars in India and across the world have studied these arts and some valuable scholarship is available on them. The folk spirit has a tremendous role to play in the development of art and in the overall consciousness of indigenous cultures.

Contextual Modernism

The year 1997 bore witness to two parallel gestures of canon formation. On the one hand, the influential Baroda Group, a coalition whose original members included Vivan Sundaram, Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh, Bhupen Khakhar, and Nalini Malani—and which had left its mark on history in the form of the 1981 exhibition “Place for People”—was definitively historicized in 1997 with the publication of Contemporary Art in Baroda, an anthology of essays edited by Sheikh. On the other hand, the art historian R. Siva Kumar's benchmark exhibition and related publication, A Contextual Modernism, restored the Santiniketan artists—Rabindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Benode Behari Mukherjee, and Ramkinkar Baij—to their proper place as the originators of an indigenously achieved yet transcultural modernism in the 1930s, well before the Progressives composed their manifesto in the late 1940s. Of the Santiniketan artists, Siva Kumar observed that they “reviewed traditional antecedents in relation to the new avenues opened up by cross-cultural contacts. They also saw it as a historical imperative. Cultural insularity, they realized, had to give way to eclecticism and cultural impurity.”[87]

The idea of Contextual Modernism emerged in 1997 from R. Siva Kumar's Santiniketan: The Making of a Contextual Modernism as a postcolonial critical tool in the understanding of an alternative modernism in the visual arts of the erstwhile colonies like India, specifically that of the Santiniketan artists.

Several terms including Paul Gilroy's counter culture of modernity and Tani Barlow's Colonial modernity have been used to describe the kind of alternative modernity that emerged in non-European contexts. Professor Gall argues that 'Contextual Modernism' is a more suited term because “the colonial in colonial modernity does not accommodate the refusal of many in colonized situations to internalize inferiority. Santiniketan's artist teachers' refusal of subordination incorporated a counter vision of modernity, which sought to correct the racial and cultural essentialism that drove and characterized imperial Western modernity and modernism. Those European modernities, projected through a triumphant British colonial power, provoked nationalist responses, equally problematic when they incorporated similar essentialisms.”[88]

According to R. Siva Kumar "The Santiniketan artists were one of the first who consciously challenged this idea of modernism by opting out of both internationalist modernism and historicist indigenousness and tried to create a context sensitive modernism."[89] He had been studying the work of the Santiniketan masters and thinking about their approach to art since the early 80s. The practice of subsuming Nandalal Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, Ram Kinker Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee under the Bengal School of Art was, according to Siva Kumar, misleading. This happened because early writers were guided by genealogies of apprenticeship rather than their styles, worldviews, and perspectives on art practice.[89]

Contextual Modernism in the recent past has found its usage in other related fields of studies, specially in Architecture.[90]

Art museums of India

Major cities

- National Museum, New Delhi

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai (formerly Prince of Wales Museum of Western India)

- Indian Museum, Kolkata

- Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad

- Government Museum (Bangalore)

- Government Museum, Chennai

- Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh

Archaeological museums

- AP State Archaeology Museum, Hyderabad

- Archaeological Museum, Thrissur

- City Museum, Hyderabad

- Government Museum, Mathura

- Government Museum, Tiruchirappalli

- Hill Palace, Tripunithura, Ernakulam

- Odisha State Museum, Bhubaneswar

- Patna Museum

- Pazhassi Raja Archaeological Museum, Kozhikode

- Sanghol Museum

- Sarnath Museum

- State Archaeological Gallery, Kolkata

- Victoria Jubilee Museum, Vijayawada

Modern art museums

- National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi – established 1954.

- National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai – established 1996.

- National Gallery of Modern Art, Bangalore – inaugurated 2009.

- Kolkata Museum of Modern Art – foundation laid in 2013.

Other museums

- Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Allahabad Museum

- Asutosh Museum of Indian Art, Kolkata

- Baroda Museum & Picture Gallery

- Goa State Museum, Panaji

- Napier Museum, Thiruvananthapuram

- National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum, New Delhi

- Sanskriti Museums, Delhi

- Watson Museum, Rajkot

- Srimanthi Bai Memorial Government Museum, Mangalore

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

| History of art |

|---|

- Indian painting

- Government College of Fine Arts, Chennai

- Indian architecture

- Crafts of India

- Rasa (art)

- Other Indian Art and Architecture forms

- Architecture of India

- Indo-Greek art

- Art of Mathura

- Gupta art

- Mauryan art

- Kushan art

- Sundari painting

- Hoysala architecture

- Vijayanagara architecture

- Greco-Buddhist art

- Chola art and architecture

- Pallava art and architecture

- Badami Chalukya architecture

Notes

- ^ Jagadish Gupta (1996). Pre-historic Indian Painting. North Central Zone Cultural Centre. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ^ Shiv Kumar Tiwari (1 January 2000s). Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-81-7625-086-3. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ Cockburn, John (1899). "Art. V.—Cave Drawings in the Kaimūr Range, North-West Provinces". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. New Series. 31 (1): 89–97. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00026113. S2CID 162764849. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2019-09-06.

- ^ Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9788170171935. Archived from the original on 2020-04-03. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2000). Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. p. 189. ISBN 9788176250863. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka (PDF). UNESCO. 2003. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2011). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 – 5000 BC. Orion. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-78022-259-2. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Javid, Ali; Jāvīd, ʻAlī; Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-87586-484-6. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Pathak, Dr. Meenakshi Dubey. "Indian Rock Art – Prehistoric Paintings of the Pachmarhi Hills". Bradshaw Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Marshall, Sir John. Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilisation, 3 vols, London: Arthur Probsthain, 1931

- ^ Keay, John, India, a History. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

- ^ Harle, 15-19

- ^ Harle, 19-20

- ^ a b Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and West. 39 (1/4): 111–143, especially 112–114, 115, 125. JSTOR 29756891.

- ^ Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and West. 39 (1/4): 111–143. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756891.

- ^ Krishan, Yuvraj; Tadikonda, Kalpana K. (1996). The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. ix-x. ISBN 978-81-215-0565-9. Archived from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ^ a b c d Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (2008). A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-470-75196-1. Archived from the original on 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ^ Harle, 22-28

- ^ Harle, 22-26

- ^ State Emblem Archived May 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Know India india.gov.in

- ^ Harle, 39-42

- ^ Dated 100 BCE in Fig.88 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL. p. 368, Fig. 88. ISBN 9789004155374. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Dalal, Roshen (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. pp. 397–398. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 430. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ "yaksha". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ Sharma, Ramesh Chandra (1994). The Splendour of Mathurā Art and Museum. D.K. Printworld. p. 76. ISBN 978-81-246-0015-3. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b c d e Boardman, John (1993). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-691-03680-2.

- ^ Fig. 85 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL. p. Fig.85, p.365. ISBN 9789004155374. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "The folk art typifies an older plastic tradition in clay and wood which was now put in stone, as seen in the massive Yaksha statuary which are also of exceptional value as models of subsequent divine images and human figures." in Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana (1965). Indian Art: A history of Indian art from the earliest times up to the third century A. D. Prithivi Prakashan. p. 84. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "With respect to large-scale iconic statuary carved in the round (...) the region of Mathura not only rivaled other areas but surpassed them in overall quality and quantity throughout the second and early first century BCE." in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL. p. 24. ISBN 9789004155374. Archived from the original on 2020-06-13. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9789004155374. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ Harle, 105-117, 26-47

- ^ Harle, 59-70

- ^ Harle, 105-117, 71-84 on Gandhara

- ^ Harle, 68-70 (but see p. 253 for another exception)

- ^ a b c Stokstad, Marilyn (2018). Art History. United States: Pearson Education. pp. 306–310. ISBN 978-0-13-447588-2.

- ^ Department of Asian Art (2000). "Shunga Dynasty (ca. Second – First Century B.C.)". Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "Indian subcontinent". Oxford Art Online. 2003. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Sarkar (2006). Hari smriti. New Delhi : Kaveri Books. p. 73. ISBN 8174790756.

- ^ a b Sarma, I.K (2001). Sri Subrahmanya Smrti. New Delhi : Sundeep Prakashan. pp. 283–290. ISBN 8175741023.

- ^ Nārāyaṇa Rāya, Udaya (2006). Art, archaeology, and cultural history of India. Delhi : B.R. Pub. Corp. ISBN 8176464929.

- ^ Xinru Liu, The Silk Road in World History, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, 42.

- ^ Lolita Nehru, Origins of the Gandharan Style, p. 63.

- ^ Chakravarti, Ranabir (2016-01-11), "Kushan Empire", The Encyclopedia of Empire, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe147, ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4

- ^ Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. Princeton University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-691-08953-9. Archived from the original on 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ^ Dhammika, Ven. S. (1994). "The Edicts of King Ashoka (an English rendering)". DharmaNet International. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

... Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, ...

- ^ "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. 1987. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Seyller, John (1987). "Scribal Notes on Mughal Manuscript Illustrations". Artibus Asiae. 48 (3/4): 247–277. doi:10.2307/3249873. JSTOR 3249873.

- ^ Fazl, Abu'l (1927). Ain-i Akbari. Translated by H Blochmann. Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ^ "Daulat". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ George Michell; Catherine Lampert; Tristram Holland (1982). In the Image of Man: The Indian Perception of the Universe Through 2000 Years of Painting and Sculpture. Alpine Fine Arts Collection. ISBN 978-0-933516-52-6. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ^ Kala, S. C. (25 June 1972). "Art of Singhal". The Economic Times. p. 5.

- ^ Hachette India (25 October 2013). Indiapedia: The All-India Factfinder. Hachette India. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-93-5009-766-3. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "For art's sake". The Hindu. February 12, 2009. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved Nov 23, 2014.

- ^ "Showcase – Artists Collectives". National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. 2012-11-09. Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ^ "National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi". Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ^ "Rabindranath Tagore: The Last Harvest". Archived from the original on 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ^ Harle, 17–20

- ^ Harle, 22–24

- ^ a b Harle, 26–38

- ^ Harle, 342-350

- ^ Harle, 87; his Part 2 covers the period

- ^ Harle, 124

- ^ Harle, 301-310, 325-327

- ^ Harle, 276–284

- ^ Chopra. et al., p. 186.

- ^ Tri. [Title needed]. p. 479.

- ^ "Prehistoric Rock Art". art-and-archaeology.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-03. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

- ^ "Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka". Archived from the original on 2007-03-08. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ "Ancient and medieval Indian cave paintings – Internet encyclopedia". Wondermondo. 2010-06-10. Archived from the original on 2018-06-24. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ Harle, 355

- ^ Harle, 361-366

- ^ Harle, 372-382

- ^ Harle, 400-406

- ^ Harle, 407-420

- ^ Untracht, Oppi. Traditional Jewelry of India. New York: Abrams, 1997 ISBN 0-8109-3886-3. p15.

- ^ Harle, 59

- ^ Glucklich, Ariel (2008). The strides of Vishnu : Hindu culture in historical perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2. OCLC 473566974.

- ^ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 36–37, 51. ISBN 978-0-7946-0011-2.

- ^ "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent". Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ^ dhokra art Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bose, Aurobindo. Folk art of India.

- ^ Thakur, Upendra (1991). Madhubani Painting. Abhinav Publications.

- ^ Upadhya, Hema (2008). Gond Art: Tribal Art of India. Rupa Publications.

- ^ GVSS, Gramin Vikas Seva Sanshtha (12 June 2011). "Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgarh and Bihar" (PDF). Planning Commission. Socio-Economic Research (SER) Division, Planning Commission, Govt. of India New Delhi. p. 53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

... globalization has triggered the emergence of a synthetic macro-culture...is gaining popularity day by day and silently engineering the gradual attrition of tribal/folk art and culture.

- ^ "Decline of tribal and folk arts lamented". Deccan Herald. Gudibanda, Karnataka, India. 3 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

In the wave of electronic media, our ... ancient culture and tribal art have been declining, ..., said folklore researcher J Srinivasaiah.

- ^ Hapgood, Susan; Hoskote, Ranjit (2015). "Abby Grey And Indian Modernism" (PDF). Grey Art Gallery. New York: New York University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Gall, David. "Overcoming Polarized Modernities: Counter-Modern Art Education: Santiniketan1Overcoming Polarized Modernities: Counter-Modern Art Education: Santiniketan, The Legacy of a Poet's School" (PDF). Hawaii University International Conferences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Humanities underground » All the Shared Experiences of the Lived World II". Archived from the original on 2014-11-20. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ ""Contextual modernism" – is it possible? Steps to improved housing strategy". 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

References

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Harsha V. Dehejia, The Advaita of Art (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2000, ISBN 81-208-1389-8), p. 97

- Kapila Vatsyayan, Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts (New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1977), p. 8

- Mitter, Partha. Indian Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-284221-8)

Further reading

- Gupta, S. P., & Asthana, S. P. (2007). Elements of Indian art: Including temple architecture, iconography & iconometry. New Delhi: Indraprastha Museum of Art and Archaeology.

- Gupta, S. P., & Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute. (2011). The roots of Indian art: A detailed study of the formative period of Indian art and architecture, third and second centuries B.C., Mauryan and late Mauryan. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation.

- Abanindranath Tagore (1914). Some Notes on Indian Artistic Anatomy. Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta. OL 6213535M.

- Kossak, Steven (1997). Indian court painting, 16th-19th century.. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-783-9. (see index: pages 148-152)

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-374-9. fully online

- Smith, Vincent A. (1930). A History Of Fine Art In India And Ceylon. The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Welch, Stuart Cary (1985). India: art and culture, 1300–1900. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-944142-13-4. fully online