Art of El Greco

El Greco (1541–1614) was a prominent painter, sculptor and architect active during the Spanish Renaissance. He developed into an artist so unique that he belongs to no conventional school. His dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but gained newfound appreciation in the 20th century.[1]

He is best known for tortuously elongated bodies and chests on the figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantine traditions with those of Western civilization.[2] Of El Greco, Hortensio Félix Paravicino, a seventeenth-century Spanish preacher and poet, said: "Crete gave him life and the painter's craft, Toledo a better homeland, where through Death he began to achieve eternal life."[3] According to author Liisa Berg, Paravacino revealed in a few words two main factors that define when a great artist gains the appraisal he deserves: no one is a prophet in his homeland and often it is in retrospect that one's work gains its true appreciation and value.[3]

Re-evaluation of his art

|

|

El Greco was disdained by the immediate generations after his death because his work was opposed in many respects to the principles of the early baroque style which came to the fore near the beginning of the 17th century and soon supplanted the last surviving traits of the 16th-century Mannerism.[1] The painter was deemed incomprehensible and had no important followers.[4] Only his son and a few unknown painters produced weak copies of El Greco's works. Later 17th- and early 18th-century Spanish commentators praised his skill but criticized his anti-naturalistic style and his complex iconography. Some of these commentators, such as Antonio Palomino and Céan Bermúdez described his mature work as "contemptible", "ridiculous" and "worthy of scorn".[5] The views of Palomino and Bermúdez were frequently repeated in Spanish historiography, adorned with terms such as "strange", "queer", "original", "eccentric" and "odd".[6] The phrase "sunk in eccentricity", often encountered in such texts, in time became his "madness".[k]

With the arrival of Romantic sentiments, El Greco's works were examined anew.[4] To French writer Théophile Gautier, El Greco was the precursor of the European Romantic movement in all its craving for the strange and the extreme.[7] French Romantic writers praised his work for the same "extravagance" and "madness" which had disturbed 18th century commentators. During the operation of the Spanish Museum in Paris, El Greco was admired as the ideal romantic hero and all the romantic stereotypes (the gifted, the misunderstood, the marginal, the mad, the one who lost his reason because of the scorn of his contemporaries) were projected onto his life.[6] The myth of El Greco's madness came in two versions. On the one hand, Théophile Gautier, a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist and literary critic, believed that El Greco went mad from excessive artistic sensitivity.[8] On the other hand, the public and the critics would not possess the ideological criteria of Gautier and would retain the image of El Greco as a "mad painter" and, therefore, his "maddest" paintings were not admired but considered to be historical documents proving his "madness".

The critic Zacharie Astruc and the scholar Paul Lefort helped to promote a widespread revival of interest in his painting. In the 1890s, Spanish painters then living in Paris adopted him as their guide and mentor.[7]

In 1908, art historian Manuel Bartolomé Cossío, who regarded El Greco's style as a response to Spanish mystics, published the first comprehensive catalogue of El Greco's works.[9] In this book, El Greco is described as the founder of the Spanish School and as the conveyor of the Spanish soul.[10] Julius Meier-Graefe, a scholar of French Impressionism, travelled in Spain in 1908 and wrote down his experiences in The Spanische Reise, the first book which established El Greco as a great painter of the past. In El Greco's work, Meier-Graefe found foreshadowings of modernity.[11] To the Der Blaue Reiter group in Munich in 1912, El Greco typified that mystical inner construction that it was the task of their generation to rediscover.[10] To the English artist and critic Roger Fry in 1920, El Greco was the archetypal genius who did as he thought best "with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public". Fry described El Greco as "an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way".[12] At the same period, some other researchers developed certain disputed theories. Doctors August Goldschmidt and Germán Beritens argued that El Greco painted such elongated human figures because he had vision problems (possibly progressive astigmatism or strabismus) that made him see bodies longer than they were, and at an angle to the perpendicular. This theory enjoyed surprising popularity during the early years of the twentieth century and was opposed by the German psychologist David Kuntz.[13] Whether or not El Greco had progressive astigmatism is still open to debate.[14] Stuart Anstis, Professor at the University of California (Department of Psychology) concludes that "even if El Greco were astigmatic, he would have adapted to it, and his figures, whether drawn from memory or life, would have had normal proportions. His elongations were an artistic expression, not a visual symptom."[15] According to Professor of Spanish John Armstrong Crow, "astigmatism could never give quality to a canvas, nor talent to a dunce".[16] The English writer W. Somerset Maugham attributed El Greco's personal style a "latent homosexuality" which he claimed the artist might have had; the doctor Arturo Perera attributed El Greco's style to the use of cannabis.[17]

El Greco's re-evaluation was not limited to just scholarship. His expressiveness and colors influenced Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet.[18] The first painter who appears to have noticed the structural code in the morphology of the mature El Greco was Paul Cézanne, one of the forerunners of cubism.[4] Comparative morphological analyses of the two painters revealed their common elements, such as the distortion of the human body, the reddish and (in appearance only) unworked backgrounds, the similarities in the rendering of space etc.[19] According to Brown, "Cézanne and El Greco are spiritual brothers despite the centuries which separate them".[20] Fry observed that Cézanne drew from "his great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme".[21]

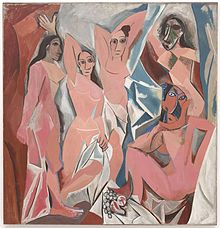

The Symbolists, and Pablo Picasso during his blue period, drew on the cold tonality of El Greco, utilizing the anatomy of his ascetic figures. While Picasso was working on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, he visited his friend Ignacio Zuloaga in his studio in Paris and studied El Greco's Opening of the Fifth Seal (owned by Zuloaga since 1897).[22] The relation between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was pinpointed in the early 1980s, when the stylistic similarities and the relationship between the motifs of both works were analysed.[23] According to art historian John Richardson Les Demoiselles d'Avignon "turns out to have a few more answers to give once we realize that the painting owes at least as much to El Greco as Cézanne".[24] Picasso said about Demoiselles d'Avignon, "in any case, only the execution counts. From this point of view, it is correct to say that Cubism has a Spanish origin and that I invented Cubism. We must look for the Spanish influence in Cézanne. Things themselves necessitate it, the influence of El Greco, a Venetian painter, on him. But his structure is Cubist".[25]

The early cubist explorations of Picasso were to uncover other aspects in the work of El Greco: structural analysis of his compositions, multi-faced refraction of form, interweaving of form and space, and special effects of highlights. Several traits of cubism, such as distortions and the materialistic rendering of time, have their analogies in El Greco's work. According to Picasso, El Greco's structure is cubist. On February 22, 1950, Picasso began his series of "paraphrases" of other painters' works with The Portrait of a Painter after El Greco.[26] Foundoulaki asserts that Picasso "completed ... the process for the activation of the painterly values of El Greco which had been started by Manet and carried on by Cézanne".[27]

The expressionists focused on the expressive distortions of El Greco. According to Franz Marc, one of the principal painters of the German expressionist movement, "we refer with pleasure and with steadfastness to the case of El Greco, because the glory of this painter is closely tied to the evolution of our new perceptions on art".[28] Jackson Pollock, a major force in the abstract expressionist movement, was also influenced by El Greco. By 1943, Pollock had completed sixty drawing compositions after El Greco and owned three books on the Cretan master.[29]

Contemporary artists are also inspired by El Greco's art. Kysa Johnson used El Greco's paintings of the Immaculate Conception as the compositional framework for some of her works, and the master's anatomical distortions are somewhat reflected in Fritz Chesnut's portraits.[30]

Technique and style

The primacy of the imagination over the subjective character of creation was a fundamental principle of El Greco's style. According to Lambraki-Plaka "intuition and the judgement of the eye are the painter's surest guide".[31]

Artistic beliefs

Scholars' conclusions about El Greco's aesthetics are mainly based on the notes El Greco inscribed in the margins of two books in his library. El Greco discarded classicist criteria such as measure and proportion. He believed that grace is the supreme quest of art. But the painter achieves grace only if he manages to solve the most complex problems with obvious ease.[31]

El Greco regarded color as the most important and the most ungovernable element of painting ("I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art."—Notes of the painter in one of his commentaries).[32] He declared that color had primacy over drawing; thus his opinion on Michelangelo was that "he was a good man, but he did not know how to paint".[31] Francisco Pacheco, a painter and theoretician who visited El Greco in 1611, was startled by the painter's technique: "If I say that Domenico Greco sets his hand to his canvases many and many times over, that he worked upon them again and again, but to leave the colors crude and unblent in great blots as a boastful display of his dexterity?"[33] Pacheco asserts that "El Greco believed in constant repainting and retouching in order to make the broad masses tell flat as in nature".[33]

Further assessments

Art historian Max Dvořák was the first scholar to connect El Greco's art with Mannerism and Antinaturalism.[34] Modern scholars characterize El Greco's theory as "typically Mannerist" and pinpoint its sources in the Neoplatonism of the Renaissance.[35] According to Brown, the painter endeavored to create a sophisticated form of art.[36] Nicholas Penny, senior curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, asserts that "once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his own – one that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting".[37]

In his mature works El Greco demonstrated a characteristic tendency to dramatize rather than to describe.[1] The strong spiritual emotion transfers from painting directly to the audience. According to Pacheco, El Greco's perturbed, violent and at times seemingly careless-in-execution art was due to a studied effort to acquire a freedom of style.[33] The preference of El Greco for very tall and slender figures and elongated compositions, which served both the expressive purposes and the aesthetic principles of the master, led him to disregard the laws of nature and elongate his compositions more and more, particularly when they were destined for altarpieces.[38] The anatomy of the human body becomes even more otherworldly in the painter's mature works. For example, for the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception that he painted for the side-chapel of Isabella Oballe in the church of Saint Vincent in Toledo (1607–1613), El Greco asked to lengthen the altarpiece itself by another 1.5 feet "because in this way the form will be perfect and not reduced, which is the worst thing that can happen to a figure'". The minutes concerning the commission, which were composed by the personnel of the municipality, describe El Greco as "one of the greatest men in both this kingdom and outside it".[39] A significant innovation of El Greco's mature works is the interweaving between form and space; a reciprocal relationship is developed between them which completely unifies the painting surface. This interweaving would re-emerge three centuries later in Cézanne's and Picasso's works.[38]

Another characteristic of El Greco's mature style is the use of light. As Brown notes, "each figure seems to carry its own light within or reflects the light that emanates from an unseen source".[40] Fernando Marias and Agustín Bustamante García, the scholars who transcribed El Greco's handwritten notes, connect the power that the painter gives to light with the ideas underlying Christian Neo-Platonism.[41] The later works of the painter turn this use of light into glowing colors. In The Vision of Saint John and the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse the scenes owe their power to this otherworldly stormy light, which reveals their mystic character.[38] The renowned View of Toledo (c. 1600) also acquires its visionary character because of this stormy light. The grey-blue clouds are split by lightning bolts, which vividly highlight the noble buildings of the city.[38] His last landscape, View and Plan of Toledo, is almost like a vision, all of the buildings painted glistening white. According to Wethey, in his surviving landscapes, "El Greco demonstrated his characteristic tendency to dramatize rather than to describe".[1] Professor Nicos Hadjinicolaou notes the manner in which El Greco could adjust his style in accordance with his surroundings and stresses the importance of Toledo for the complete development of El Greco's mature style.[42]

Wethey asserts that "although Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, the artist became so immersed in the religious environment of Spain that he became the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism". The same scholar believes that in El Greco's mature works "the devotional intensity of mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the period of the Counter-Reformation".[1] El Greco often produces an open pipe between Earth and Heaven in his paintings. The Annunciation is one example of this spiritual conduit being present. The people, clouds, and other objects in many of his paintings open away from a central, empty passageway between the ground and the upper spiritual firmament. This is sometimes a subtle concavity in fabrics that implies a ghostly passageway that leads vertically from the people at the bottom to the angels at the top of the paintings. In other paintings, this central cylinder of open space is very prominent, providing a distinctive visionary style, due to the deep insights of the pious painter. These paintings imply that El Greco, himself, can see the holy path from common human existence toward a very real Heaven.

El Greco excelled also as a portraitist, mainly of ecclesiastics or gentlemen, who was able not only to record a sitter's features but to convey his character.[43] Although he was primarily a painter of religious subjects, his portraits, though less numerous, are equally high in quality. Two of his late works are the portraits of Fray Felix Hortensio Paravicino (1609) and Cardinal Don Fernando Niño de Guevara (c. 1600). Both are seated, as was customary in portraits presenting important ecclesiastics. Wethey says that "by such simple means, the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank as a portraitist, along with Titian and Rembrandt".[1]

Suggested Byzantine affinities

During the first half of the 20th century some scholars developed certain theories concerning the Byzantine origins of El Greco's style. Professor Angelo Procopiou had asserted that, although El Greco belongs to Mannerism, his roots were firmly in the Byzantine tradition.[44] According to art historian Robert Byron "all Greco's most individual characteristics, which have so puzzled and dismayed his critics, derive directly from the art of his ancestors".[45] On the other hand, Cossío had argued that Byzantine art could not be related to El Greco's later work.[46]

The discovery of the Dormition of the Virgin on Syros, an authentic and signed work from the painter's Cretan period (the iconographic type of the Dormition was suggested as the compositional model for the Burial of the Count of Orgaz for quite some time),[45] and the extensive archival research in the early 1960s contributed to the rekindling and reassessment of these theories. Significant scholarly works of the second half of the 20th century devoted to El Greco reappraise many of the various interpretations of him, including his supposed Byzantinism.[47] Based on the notes written in El Greco's own hand and on his unique style, they see an organic continuity between Byzantine painting and his art.[48] German art historian August L. Mayer emphasizes what he calls "the oriental element" in El Greco's art. He argues that the artist "remained a Greek reflecting vividly the Oriental side of Byzantine culture ... The fact that he signed his name in Greek characters is no mere accident".[49] In this judgement, Mayer disagrees with Oxford University professors, Cyril Mango and Elizabeth Jeffreys, who assert that "despite claims to the contrary, the only Byzantine element of his famous paintings was his signature in Greek lettering".[50] Hadjinicolaou, another scholar who is opposed to the persistence of El Greco's Byzantine origins, states that from 1570 on the master's painting is "neither Byzantine nor post-Byzantine but Western European. The works he produced in Italy belong to the history of the Italian art, and those he produced in Spain to the history of Spanish art".[51]

The Welsh art historian David Davies seeks the roots of El Greco's style in the intellectual sources of his Greek-Christian education and in the world of his recollections from the liturgical and ceremonial aspect of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Davies believes that the religious climate of the Counter-Reformation and the aesthetics of mannerism acted as catalysts to activate his individual technique. According to Davies, "El Greco sought to convey the essential or universal meaning of the subject through a process of redefinition and reduction. In Toledo, he accomplished this by abandoning the Renaissance emphasis on the observation and selection of natural phenomena. Instead he responded to Byzantine and sixteenth-century Mannerist art in which images are conceived in the mind".[52] Additionally, he asserts that the philosophies of Platonism and ancient Neo-Platonism, the works of Plotinus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, and the texts of the Church fathers and the liturgy offer the keys to the understanding of El Greco's style.[52]

Summarizing the ensuing scholarly debate on this issue, José Álvarez Lopera, curator at the Museo del Prado, concludes that the presence of "Byzantine memories" is obvious in El Greco's mature works, though there are still some obscure issues about El Greco's Byzantine origins needing further illumination.[53] According to Lambraki-Plaka "far from the influence of Italy, in a neutral place which was intellectually similar to his birthplace, Candia, the Byzantine elements of his education emerged and played a catalytic role in the new conception of the image which is presented to us in his mature work".[54] According to Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco employed a deliberately non-naturalistic style and his completely spiritualized figures are a reference to the ascetics of Byzantine hagiography.[55]

Architecture and sculpture

El Greco in his lifetime was highly esteemed as an architect and sculptor.[56] He usually designed complete altar compositions, working as architect and sculptor as well as painter, for instance at the Hospital de la Caridad. There he decorated the chapel of the hospital, but the wooden altar and the sculptures he executed have in all probability perished.[57] For Espolio the master designed the original altar of gilded wood which has been destroyed, but his small, sculptured group of the Miracle of St. Ildefonso still survives on the lower centre of the frame.[1]

| "I would not be happy to see a beautiful, well-proportioned woman, no matter from which point of view, however extravagant, not only lose her beauty in order to, I would say, increase in size according to the law of vision, but no longer appear beautiful, and, in fact, become monstrous." |

| El Greco (marginalia the painter inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius)[58] |

His most important architectural achievement was the church and Monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, for which he also executed sculptures and paintings.[59] El Greco is regarded as a painter who incorporated architecture in his painting. He is also credited with the architectural frames to his own paintings in Toledo. Pacheco characterized him as "a writer of painting, sculpture and architecture".[31]

In the marginalia El Greco inscribed in his copy of Daniele Barbaro's translation of Vitruvius' De Architectura, he refuted Vitruvius' attachment to archaeological remains, canonical proportions, perspective and mathematics. He also saw Vitruvius's manner of distorting proportions in order to compensate for distance from the eye as responsible for creating monstrous forms.[60] El Greco was averse to the very idea of rules in architecture; he believed above all in the freedom of invention and defended novelty, variety, and complexity. These ideas were, however, far too extreme for the architectural circles of his era and had no immediate resonance.[60]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Greco, El". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- ^ M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco-The Greek, 60

- ^ a b L. Berg, El Greco in Toledo Archived June 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco-The Greek, 49

- ^ Brown-Mann, Spanish Paintings, 43

* E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to Cézanne, 100–101 - ^ a b E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to Cézanne, 100–101

- ^ a b J. Russel, Seeing The Art Of El Greco As Never Before

- ^ T. Gautier, Voyage en Espagne, 217

- ^ Brown-Mann, Spanish Paintings, 43

- ^ a b E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to Cézanne, 103

- ^ J.J. Sheehan, Museums in the German Art World, 150

- ^ M. Kimmelmann, El Greco, Bearer Of Many Gifts

- ^ R.M. Helm, The Neoplatonic Tradition in the Art of El Greco, 93–94

* M. Tazartes, El Greco, 68–69 - ^ I. Grierson, The Eye Book, 115

- ^ S. Anstis, Was El Greco Astigmatic, 208

- ^ J.A. Crow, Spain: The Root and the Flower, 216

- ^ M. Tazartes, El Greco, 68–69

- ^ H.E. Wethey, El Greco and his School, II, 55

- ^ E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to Cézanne, 105–106

- ^ J. Brown, El Greco, the Man and the Myths, 28

- ^ M. Lambraki-Plaka, From El Greco to Cézanne, 15

- ^ C.B. Horsley, The Shock of the Old

- ^ R. Johnson, Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon, 102–113

- ^ J. Richardson, Picasso's Apocalyptic Whorehouse, 40–47

- ^ D. de la Souchère, Picasso à Antibes, 15

- ^ E. Foundoulaki, From El Greco to Cézanne, 111

- ^ E. Foundoulaki, Reading El Greco through Manet, 40–47

- ^ Kandinsky-Marc, Blaue Reiter, 75–76

- ^ J.T. Valliere, The El Greco Influence on Jackson Pollock, 6–9

- ^ H.A. Harrison, Getting in Touch With That Inner El Greco

- ^ a b c d M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco-The Greek, 47–49

- ^ Marias-Bustamante, Las Ideas Artísticas de El Greco, 80

- ^ a b c A. E. Landon, Reincarnation Magazine 1925, 330

- ^ J.A. Lopera, El Greco: From Crete to Toledo, 20–21

- ^ J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 110

* F. Marias, El Greco's Artistic Thought, 183–184 - ^ J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 110

- ^ N. Penny, At the National Gallery

- ^ a b c d M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco, 57–59

- ^ J. Gudiol, El Greco, 252

- ^ J. Brown, El Greco and Toledo, 136

- ^ Marias-Bustamante, Las Ideas Artísticas de El Greco, 52

- ^ N. Hadjinikolaou, Inequalities in the work of Theotocópoulos, 89–133

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, El Greco

- ^ A. Procopiou, El Greco and Cretan Painting, 74

- ^ a b R. Byron, Greco: The Epilogue to Byzantine Culture, 160–174

- ^ M.B Cossío, El Greco, 501–512

- ^ Cormack-Vassilaki, The Baptism of Christ Archived 2009-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ R.M. Helm, The Neoplatonic Tradition in the Art of El Greco, 93–94

- ^ A.L. Mayer, El Greco-An Oriental Artist, 146

- ^ Mango-Jeffreys, Towards a Franco-Greek Culture, 305

- ^ N. Hadjinikolaou, El Greco, 450 Years from his Birth, 92

- ^ a b D. Davies, "The Influence of Neo-Platonism on El Greco", 20 etc.

* D. Davies, the Byzantine Legacy in the Art of El Greco, 425–445 - ^ J.A. Lopera, El Greco: From Crete to Toledo, 18–19

- ^ M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco, the Puzzle, 19

- ^ M. Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco, 54

- ^ W. Griffith, Historic Shrines of Spain, 184

- ^ E. Harris, A Decorative Scheme by El Greco, 154

- ^ Lefaivre-Tzonis, The Emergence of Modern Architecture, 165

- ^ I. Allardyce, Historic Shrines of Spain, 174

- ^ a b Lefaivre-Tzonis, The Emergence of Modern Architecture, 164