Arson in royal dockyards

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the better securing and preserving His Majesty's Dock Yards, Magazines, Ships, Ammunition, and Stores. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 12 Geo. 3. c. 24 |

| Introduced by | Sir Charles Whitworth[2] |

| Territorial extent | British Empire |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 16 April 1772[3] |

| Commencement | 21 January 1772[4] |

| Repealed | 14 October 1971[5] |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | Statute Law Revision Act 1888 |

| Repealed by | Criminal Damage Act 1971[5] |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

Arson in royal dockyards and armories was a criminal offence in the United Kingdom and the British Empire. It was among the last offences that were punishable by capital punishment in the United Kingdom. The crime was created by the Dockyards etc. Protection Act 1772 (12 Geo. 3. c. 24) passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, which was designed to prevent arson and sabotage against vessels, dockyards, and arsenals of the Royal Navy.

It remained one of the few capital offences after reform of the death penalty in 1861, and remained in effect even after the death penalty was permanently abolished for murder in 1969. However, it was eliminated by the Criminal Damage Act 1971.[5]

Passage

The Dockyards &c. Protection Act 1772 was passed in order to protect military materiel from damage. At the time, ships were built of flammable oak wood and tar, and the naval yards were full of these supplies.[6] Punishment for violating the act was a death sentence without benefit of clergy.[7][6]

The act's first section made it an offence, anywhere in the British Empire, to "wilfully and maliciously burn, set on fire, or otherwise destroy":—[7]

- "His Majesty's ships or vessels of war", whether afloat or being built, in a Royal Dockyard or private dockyard;

- buildings or materials in royal dockyards or ropeyards;

- buildings or contents of "military, naval, or victualling stores".

The same punishment was mandated for aiding and abetting.

The second section allowed offences occurring outside the Kingdom of Great Britain to be tried in any assize court of England and Wales or sheriff court of Scotland.[8][9]

At the time of the act's passage, the death penalty was common under the "Bloody Code";[10] at the turn of the 19th century, 220 offences carried the death penalty.[11] Setting fire was already a common law offence (arson in England and Wales,[12] punishable by death with benefit of clergy;[10] wilful fire raising in Scots law.[13]) and setting fire to mills and coal mines were capital statutory offences without benefit of clergy.[14] The 1772 act was categorised, under "offences against the monarch" (lèse-majesté), as "injuring the king's armour", together with a 1589 act which imposed a death sentence for stealing or removing ordnance or naval stores of value greater than 20 shillings.[15][16]

While the Dockyards etc. Protection Act 1772 applied to anybody, Royal Navy personnel were already subject to the Navy Act 1661 and its 1748 replacement, which prescribed death for setting fire to any ships or stores other than enemy vessels.[17][18]

Prosecution

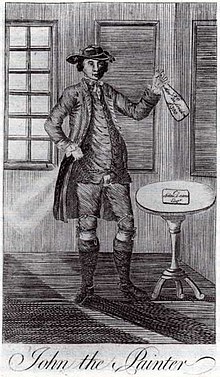

Only one prosecution is known to have been brought under the 1772 act;[19][20] The Scottish saboteur John the Painter (also known as James Hill or John Aitken) was tried in March 1777 at the Hampshire spring assizes in Winchester Castle, for having set fire to the rope house at Portsmouth Royal Dockyard the previous December.[21][22] He was found guilty and hanged from the mizzenmast of the frigate HMS Arethusa, the highest gallows erected in British history,[23] with the ship moored at Portsmouth Royal Dockyards within view of the damage he had caused.[22] A crowd of 20,000 gathered to witness the hanging.[23] John the Painter had also tried to burn merchant vessels in Bristol, in response to which a bill was introduced in the Commons extending the 1772 act from naval to private ships and docks; but it was dropped at committee stage.[24]

The indictment against John the Painter charged that he "feloniously, wilfully, and maliciously, [certain buildings, hemp, ropes and cordage] did set on fire and burn, and cause and procure to be set on fire and burnt, against the form of the statute in such case lately made and provided, and against the peace of our said lord the king, his crown and dignity".[20] The sample indictment in the 1922 edition of Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice states the offence as "Arson, contrary to section 1 of the Dockyards Protection Act, 1772."[25] The offence was not triable at quarter sessions.[25]

After the June 1772 burning of HMS Gaspee in Warwick, Rhode Island, the Earl of Hillsborough as Secretary of State for the Colonies proposed invoking the act, but Edward Thurlow and Alexander Wedderburn, the chief English law officers, advised that it did not apply since the Gaspee had not been in a dockyard.[26]

The systematic collection of criminal statistics for England and Wales began in 1856, and record no further sentences under the 1772 act.[27] In 1913 suspicions that the suffragette arson campaign would target a royal dockyard were fanned by a letter discovered in April and the fire in December at Portsmouth semaphore tower; some reports of both incidents mentioned the capital offence.[28] Sabotage was initially suspected after a 1950 explosion at DM Gosport in Portsmouth, and Sir Jocelyn Lucas asked during question time whether the 1772 act would be applied to the perpetrators; Clement Attlee's reply was noncommittal.[29]

Amendment and repeal

The offence created by the 1772 act was included in the Judgment of Death Act 1823 among those for which the judge could record a death sentence while substituting a lesser one.[30] It was among those for which the 1837 Punishment of Offences Bill, as introduced, proposed to reduce the penalty from death to transportation. However, the House of Lords deleted this provision in committee on the ground that the offence was tantamount to treason.[31][32][33] For a like reason, the Commons voted to exclude it from Lord John Russell's 1840 Substitution of Punishments of Death Bill and its enacted 1841 version.[32][33] Russell introduced a separate bill in 1841 specifically to tighten the wording of the 1772 act to remove the penalty in "cases in which there might be no destruction of naval stores, no treasonable intent, nor any view to cripple the resources of this country".[34] The Criminal Law Consolidation Acts 1861 sharply limited the death penalty for civilians to only five crimes, namely: arson in royal dockyards, murder, treason, espionage, and piracy with violence.[35] Of the 1861 acts, the Criminal Statutes Repeal Bill originally proposed repealing the 1772 act "as to the United Kingdom" but this was again deleted at committee.[36] Unsuccessful Disraeli ministry bills of 1878 and 1879, which attempted to establish a criminal code for England (and Wales) and Ireland, would have repealed the 1772 act in those jurisdictions and made arson in royal dockyards a capital offence only in wartime.[37][38] The Blackburn Commission, which drafted the 1879 bill, suggested alternatively deleting the offence altogether and punishing as simple arson instead.[39]

The above bills and acts applied to England and Wales, and most also to Ireland, but not to Scotland. The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1887 restricted capital punishment there to murder, attempted murder, and treason, implicitly abolishing it for the 1772 offence.[40]

The Naval Discipline Acts of 1860 to 1866, which replaced the Navy Act 1748, permitted lesser penalties than death for its firesetting offence.[41][42] Under the Naval Discipline Act 1957, which replaced the 1866 act, arson in dockyards came under "destruction of public and service property", punishable by imprisonment.[43]

The Statute Law Revision Act 1888 deleted the superfluous enacting formula from section 2 of the 1772 act.[44] The short title "Dockyards etc. Protection Act 1772" was assigned by the Short Titles Act 1892 and again by the Short Titles Act 1896. The Children Act 1908 (8 Edw. 7. c. 67) removed the death penalty for under-16s.

The Attlee ministry's Criminal Justice Bill 1948 was amended by the House of Commons so that the death penalty for murder would be abolished, and that during peacetime the suspension would extend to other capital offences including arson in royal dockyards.[45][46] However, this was not accepted by the House of Lords, and eventually the bill as enacted omitted these provisions,[47] although an unofficial suspension of the death penalty lasted for several months.[46][48]

The Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965 temporarily abolishing the death penalty for murder was made permanent by parliamentary resolution in 1969,[49] leaving the provisions of the Dockyards etc. Protection Act 1772 as one of the four civilian crimes that retained the death penalty.[35] The Criminal Law Act 1967 removed the obsolete references to assize courts and "benefit of clergy" from the 1772 act.[50]

Various acts and subordinate legislation made non-textual amendments extending the scope of the 1772 act so that by 1970 it applied to "naval vessels, naval, military or Air Force installations and certain property vested in the Minister of Technology".[19] That year, the Law Commission's report on the law on criminal damage proposed that the crime be abolished in its draft consolidation bill.[19] This came after the fact that the law was no longer required for its original purposes, as warships were no longer made of flammable materials.[6] The resulting Criminal Damage Act 1971 duly repealed the 1772 act and abolished the offence of arson in royal dockyards and armories.[5][51]

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 and the Human Rights Act 1998 abolished the death penalty for all remaining crimes.[52] In a speech in the House of Lords on the Crime and Disorder Bill, Lord Goodhart stated that the dockyard arson offence disappeared from the list of capital crimes in 1971 "without, so far as I am aware, either comment or concern."[53]

Despite abolition in the United Kingdom, a 2004 episode of the comedy quiz show QI asserted that it is still popularly and erroneously believed that arson in royal dockyards continues to exist as a capital offence.[54][55] Though similar crimes have occurred since abolition, they are now dealt with under general laws relating to arson.[56]

Applicability outside the United Kingdom

The offence defined in the act could be committed "either within this Realm, or in any of the Islands, Countries, Forts, or Places thereunto belonging". Once a British colony or territory gained its own legislature, its domestic law might explicitly or implicitly incorporate the 1772 act via a reception statute. Some Westminster amendments to the 1772 act did not automatically extend outside the United Kingdom, including the 1971 repeal.[5]

Jefferson's Summary View of the Rights of British America and the resulting Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress objected to the act's change of venue provision allowing Americans to be brought from the Thirteen Colonies to Great Britain for trial.[57][58]

In Australasia, the 1772 act was explicitly repealed by local legislatures establishing criminal codes for the jurisdictions of New Zealand (1893[59]), Queensland (1899[60]), and Western Australia (1901[61]). Tasmania's Criminal Code Act 1924 had a general repeal of all "penal enactments" of the Imperial (Westminster) parliament.[62] A 1975 report for Victoria found that the 1772 act was still apparently in force there, as the sections of the 1971 Westminster repeal applied only to the United Kingdom;[8] however, the offence of arson in royal dockyards was obsolete, as the provisions have been superseded by the state's Crimes Act 1958 and the federal Crimes Act 1914 as amended.[8] New South Wales also retained the 1772 act, as it was viewed as being ultra vires for its parliament to amend it.[8] The law reform commission of South Australia recommended repealing the 1772 act in 1986, saying it would not have been possible before the Australia Act 1986 amended the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865.[63]

In Upper Canada, an 1833 act abolishing the death penalty for many offences specifically excluded the 1772 British act.[64] In 1869, shortly after Canadian Confederation, the federal parliament passed an act based on the British Malicious Damage Act 1861; unlike the 1861 act, the 1869 act reduced the punishment for arson in royal dockyards to a term of imprisonment between two years and life.[65] The 1886 replacement of the 1869 act changed this to a mandatory life sentence.[66] The Canadian Criminal Code introduced in 1892 was modelled on the 1879 UK bill but omitted the section which retained the crime of arson in royal dockyards,[67] and repealed the 1886 Canadian act.[68]

The British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar had the act incorporated into its law in the English Law (Application) Act 1962. Thus, the offence was retained in Gibraltarian law; however, section two was repealed in 1972.[69]

The 1772 act was formally repealed in the law of the Republic of Ireland by the Statute Law Revision Act 2007, without implying that it had previously been in force.[70] The 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State said earlier statutes would remain in force unless incompatible with its provisions;[71] similarly to the 1937 Constitution of Ireland.[72]

Sources

- 22 Geo. 3. c. 24 Act for the Better Securing of His Majesty's Dock Yards, Magazines, Ships, Ammunition, and Stores (1772) text of act as passed

- "Dock-yards &c". Journals of the House of Commons. 33: 608, 630, 637, 656, 667, 669, 676, 696, 701. March–April 1772.

- "Dock-yards &c. Bill". Journals of the House of Lords. 33: 352, 355, 360, 363, 364. April 1772.

- Halsbury, Hardinge Stanley Giffard, Earl of (1909). The Laws of England (1st ed.). London: Butterworth.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McLynn, Frank (17 June 2013) [1989]. Crime and Punishment in Eighteenth Century England. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-09316-6. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- Roome, Henry Delacombe; Ross, Robert Ernest (1922). Archbold's Pleading, Evidence, & Practice in Criminal Cases (26th ed.). London: Sweet and Maxwell.

Citations

- ^ The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by the Short Titles Act 1896, section 1 and the first schedule. Due to the repeal of those provisions it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978.

- ^ Journals of the House of Commons v.33 p. 630

- ^ Journals of the House of Commons v.33 p. 701

- ^ Start of 5th session of 13th Parliament of Great Britain

- ^ a b c d e "Criminal Damage Act 1971 [as enacted]". Legislation.gov.uk. ss. 11(2), 11(8), 12(1), Schedule Part III. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Martin David. "'A Solution to the 'Mikado' Problem: Updating Construction and the Separation of Powers'". Edinburgh Postgraduate Law Conference. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ a b Halsbury 1909 "Relations Between the Crown and Subject" Vol. VI p. 357 s. 516

- ^ a b c d Kewley, Gretchen (11 June 1975). Report On The Imperial Acts Application Act 1922 (PDF) (Report). Parliament of Victoria. pp. 106–107. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Roome & Ross 1922 p. 31 "Jurisdiction; Burning, etc., King's ships."

- ^ a b McLynn 2013 "Introduction" p. xi

- ^ Gregory, Derek (2013). Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror, and Political Violence. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1135929060.

- ^ William Blackstone (1765–1769). "Of Offenses against the Habitations of Individuals [Book the Fourth, Chapter the Sixteenth]". Commentaries on the Laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press (reproduced on The Avalon Project at Yale Law School). Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^

- "Fire Safety Support and Education: Information for Partner Organisations" (PDF). Scottish Fire and Rescue Service. 18 March 2022. p. 2. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

Wilful fire raising (Arson in England and Wales) is a legal term.

- Prins, Herschel (17 August 2015). "Arson – or 'what you will'". Offenders, Deviants Or Patients? An Introduction to Clinical Criminology (5th ed.). London. p. 305. doi:10.4324/9781315712413-18. ISBN 9781315712413.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- "Fire Safety Support and Education: Information for Partner Organisations" (PDF). Scottish Fire and Rescue Service. 18 March 2022. p. 2. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ 10 Geo. 2 c. 32 s. 6; 9 Geo. 3 c. 29 s. 2; cited by Radzinowicz, L. (1945). "The Waltham Black Act: A Study of the Legislative Attitude towards Crime in the Eighteenth Century". The Cambridge Law Journal. 9 (1): 76 fn. 73. doi:10.1017/S0008197300122639. ISSN 0008-1973. JSTOR 4503507. S2CID 144547451.

- ^ 31 Eliz. 1 c. 4, amended by 22 Cha. 2. c. 5; McLynn 2013 "Property Crime" p. 94

- ^

- Hawkins, William; Curwood, John (1824). "III: Offences Against the King ; 5: Injuring the King's Armour". A Treatise of the Pleas of the Crown (8th ed.). London: S. Sweet; R. Pheney; A. Maxwell; R. Stevens; J. Cumming. p. 50.

- Riddell, Henry; Rogers, John Warrington (1848). "Offences Against Queen and Government : Offences tending to impair National Defences". An Index to the Public Statutes. Vol. I. London: W. Benning. p. 257.

- ^ An Act for the Establishing Articles and Orders for the regulateing and better Government of His Majesties Navies Ships of Warr & Forces by Sea [13 Cha. 2. St. 1. c. 9] s. 26

- ^ An Act for amending, explaining, and reducing into One Act of Parliament, the Laws relating to the Government of His Majesty's Ships, Vessels, and Forces by Sea [22 Geo. 2. c. 33] s. 24

- ^ a b c The Law Commission (23 July 1970). Criminal Law : Report on offences of damage to property (PDF) (Report). Law Com. Vol. 29. London: HMSO. pp. 6, 22–23, 50. ISBN 0102091714. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ a b R. v. Hill (1777) 20 St. Tr. 1317

- ^ Holgate, Andrew (13 February 2005). "Biography: John The Painter by Jessica Warner". The Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ a b "1776 - Jack the Painter". Portsmouth Royal Dockyard Historical Trust. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ a b Ian Pindar (5 March 2005). "Review: John the Painter by Jessica Warner". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Debates; May 13". The Parliamentary Register: Or, History of the Proceedings and Debates of the House of Commons. Vol. 7. London: J. Almon. 1777. pp. 175–182.

- ^ a b Roome & Ross 1922 pp. 751–752 "Indictment for setting Fire to Ships of War, etc."

- ^

- Morgan, Gwenda; Rushton, Peter (2015). "Arson, Treason and Plot: Britain, America and the Law, 1770–1777" (PDF). History. 100 (3 (341)): 385. doi:10.1111/1468-229X.12111. ISSN 0018-2648. JSTOR 24809702.

But they also judged that the dockyards act might be difficult to implement, as it extended only to 'such ships as are burnt or otherwise destroyed in some Dockyard and not to Ships upon active Service'.

- Leslie, William R. (1952). "The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 39 (2): 239. doi:10.2307/1892182. ISSN 0161-391X. JSTOR 1892182.

- Morgan, Gwenda; Rushton, Peter (2015). "Arson, Treason and Plot: Britain, America and the Law, 1770–1777" (PDF). History. 100 (3 (341)): 385. doi:10.1111/1468-229X.12111. ISSN 0018-2648. JSTOR 24809702.

- ^ Jenkins, Roy (21 December 1966). "Piracy and Arson (Death Sentences)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). HC Deb vol 738 cc348-9W. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^

- Bearman, C. J. (2005). "An Examination of Suffragette Violence". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 381, 383. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei119. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 3490924.

- "Mansion destroyed by militants". Pall Mall Gazette. 9 May 1913. p. 3 col. 5.

Apropos the fire outrages by Suffragettes, the "Daily Dispatch" points out today that in certain circumstances arson is still a capital offence.

- "The Talk of the Town". Pall Mall Gazette. 9 May 1913. p. 4 col. 3.

The militants who have talked so glibly of burning down one of the Royal dockyards are probably unaware that this is capital offence.

- "The Portsmouth Fire". Manchester Courier. 23 December 1913. p. 6 col. 3.

Subsequent investigation goes to show that there does not seem to be any truth in the report first circulated to the effect that the disastrous fire in the Portsmouth dockyard was the work of the suffragists. It is not generally known that arson in royal dockyard or arsenal is crime that may be punished by death.

- ^ "Sabotage (Penalties)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 27 July 1950. HC Deb vol 478 c684. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Halsbury 1909 "Criminal Law and Procedure" Vol. IX s. 734 p. 376 fn. s

- ^ Correspondence between the Secretary of State of the Home Department and the Commissioners for inquiring into the State of the Criminal Law. Sessional papers. Vol. HC 1837 v. 31 (76) 31. 15 September 2023. p. 10.

- ^ a b HC Deb 15 July 1840 vol 55 cc742–3

- ^ a b "Punishment of Death Bill". General Index of Divisions of the House 1836–1850. Sessional papers. Vol. HC 1850 v. 48 (699) 1. 9 August 1850. p. 245.

- ^ Russell, Lord John (8 March 1841). "Amendment of the Criminal Law". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ a b Croker, Charlie (2010). 8 Out of 10 Brits: Intriguing and Useless Statistics about the World's 79th Largest Nation. Random House. p. 175. ISBN 978-0099532866.

- ^ Compare Criminal Statutes Repeal Bill

- as introduced (14 February 1861): (HC 1861 v. 1 (24) 785 p. 5)

- as amended by Select Committee (2 May 1861): HC 1861 v. 1 (124) 790 pp. 4–5

- ^

- Criminal Code (Indictable Offences) Bill 1878 [HC 1878–9 v. 2 (178) 5] s. 38, s. 425, Second Schedule Part I

- Criminal Code (Indictable Offences) Bill 1879 [HC 1879 v. 2 (170) 427] s. 81, s. 552, Second Schedule Part I

- ^ Harris, Seymour Frederick (1884). Principles of the Criminal Law (3rd ed.). London: Stevens and Haynes. pp. 518–520.

- ^ Criminal Code Bill Commission (1879). Report of the Royal Commission appointed to consider the Law relating to Indictable Offences, with an Appendix, containing a Draft Code embodying the Suggestions of the Commissioners. Sessional papers. Vol. HC 1878–9 xx 169. London: HMSO. p. 19. Command paper C. 2345.

- ^

- Select Committee on Capital Punishment (9 December 1930). "The Death Penalty in Scotland". Report. Sessional papers. Vol. HC 1930–31 (15). London: HMSO. p. 13 §§47–48.

it was not until the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act, 1887, ... that the capital penalty was removed from such crimes as robbery, rape, incest, wilful fire-raising, piracy with violence and the destruction of His Majesty's ships-of-war, dockyards, arsenals, and the like.

- Greer, Philippa (18 June 2012). "From death to life". Journal of the Law Society of Scotland. 57 (6). Retrieved 13 June 2023.

the death penalty was eventually restricted by the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1887 to cases of murder, attempted murder and treason.

- "Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1887". legislation.gov.uk. §§ 56, 74, 75. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- Criminal Law (Scotland) Act 1829 (10 Geo. 4. c. 38)

- Select Committee on Capital Punishment (9 December 1930). "The Death Penalty in Scotland". Report. Sessional papers. Vol. HC 1930–31 (15). London: HMSO. p. 13 §§47–48.

- ^ Naval Discipline Act 1860 (23 & 24 Vict. c. 123) s. 30; Naval Discipline Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict. c. 115) s. 30; Naval Discipline Act 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 119) s. 30; Naval Discipline Act 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 109) s. 34

- ^ Roome & Ross 1922 p. 748 "Setting Fire to or Destroying Ships, etc."

- ^ Naval Discipline Act 1957 ss. 29, 137; Sixth Schedule

- ^ Statute Law Revision Act 1888 [51 Vict. c. 3] preamble, s. 1(1) and Schedule Part I

- ^ "Traitors not to Hang". Daily Herald. London. 17 April 1948. p. 1.

- ^ a b Bailey, Victor (2000). "The Shadow of the Gallows: The Death Penalty and the British Labour Government, 1945–51" (PDF). Law and History Review. 18 (2): 305–350. doi:10.2307/744298. hdl:1808/16647. JSTOR 744298. S2CID 143024383. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Hart, Stephen (2021). James Chuter Ede: Humane Reformer and Politician. Pen & Sword. ISBN 9781526783721.

- ^ "Criminal Justice Act 1948 [1948 c. 58]". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Hansard: HC Deb 16 December 1969 vol 793 cc1297, HL Deb 18 December 1969 vol 306 cc1264-1321; "MPs vote to abolish hanging". BBC. 16 December 1969. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. 58) Schedule III Part 3". Legislation.data.gov.uk. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "The Criminal Damage Act 1971". The Journal of Criminal Law. 36 (3): 185–187. July–September 1972. doi:10.1177/002201837203600307. S2CID 220191230.; The Lord Chancellor (14 July 1971). "Royal Assent". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. col. 431.

- ^ Hood, Roger; Hoyle, Carolyn (2015). The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 56.

- ^ Lord Goodhart (12 February 1998). "Crime and Disorder Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. col. 1347–1350.

- ^ "Beavers". QI. Series 2. Episode 6. 5 November 2004. Event occurs at 25:45. BBC. BBC 2.

- ^ "QI Series B, Episode 6 – Beavers". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ "Navy chef jailed for Portsmouth Dockyard arson". Portsmouth News. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. "A Summary View of the Rights of British America". The Avalon Project. Yale University: Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Kurland, Philip B.; Lerner, Ralph, eds. (1986). "Chapter 1: Fundamental Documents; Document 1: The Continental Congress, Declaration and Resolves". The Founders' Constitution. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

Also 12 Geo. III. ch. 24. intituled, "An act for the better securing his majesty's dockyards, magazines, ships, ammunition, and stores," which declares a new offence in America, and deprives the American subject of a constitutional trial by jury of the vicinage, by authorising the trial of any person, charged with the committing any offence described in the said act, out of the realm, to be indicted and tried for the same in any shire or county within the realm.

- ^ Criminal Code Act 1893 s. 422 and Schedule 3 Part I

- ^ Criminal Code Act 1899 s. 3(1) and Schedule 2; "Alphabetical table of Imperial legislation no longer applying in Queensland" (PDF). Queensland Legislation. Queensland Government. 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

(Warships) Act 1772 12 Geo 3 c 24 (rep 1899 63 Vic No. 9 s 3 sch 2)*

- ^ Criminal Code Act 1902 s. 3(1) and Schedule 2

- ^ Criminal Code Act 1924 s. 3(1)

- ^ Law Reform Committee of South Australia (1986). Relating to the Inherited Imperial Law and to Statutes Previously Covered by the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 (Report). Vol. 102. pp. 3, 5.

- ^ 3 Will 4 c 4 (U.C.) s 14

- ^ 32 & 33 Vict. c. 22 s. 5

- ^ 49 Vict. c. 168 s. 6

- ^ compare Criminal Code Bill 1879 ss. 80–82 with Criminal Code 1892 ss. 71–72

- ^ Criminal Code 1892 [55–56 Vict c. 29] s. 981(1), and Schedule 2

- ^ "English Law (Application) Act [Act. No. 1962-17]" (PDF). Laws of Gibraltar. Government of Gibraltar. Appendix 2: Acts of the Parliament at Westminster that have been disapplied since 1 June 1962. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Statutes of Great Britain Affected: 1772". Irish Statute Book. 13 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.; "Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 (Bill 5 of 2007) Explanatory Memorandum" (PDF). Oireachtas. 1 February 2007. p. 2: Section 3; Subsection (3). Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Third Dáil sitting as a Constituent Assembly (25 October 1922). "Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922; First Schedule". electronic Irish Statute Book. Attorney General of Ireland. Article 73. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ 8th Dáil (14 June 1937). "Constitution of Ireland". electronic Irish Statute Book. Attorney General of Ireland. Article 50.1. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)