Argentine wine

Argentina is the fifth largest producer of wine in the world.[2] Argentine wine, as with some aspects of Argentine cuisine, has its roots in colonial Spain, as well in the subsequent large Spanish and Italian immigration which installed its mass consumption.[3][4][5][6] During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, vine cuttings were brought to Santiago del Estero in 1557, and the cultivation of the grape and wine production stretched first to neighboring regions, and then to other parts of the country.[citation needed]

Historically, Argentine winemakers were traditionally more interested in quantity than quality.[5] The country's wine industry exploded in the 1880s and into the early 20th century as the result of a rapidly growing population, the immigration of new producers, workers, and consumers from other wine regions (Italy and Spain), and the completion of a railroad between Mendoza and Buenos Aires.[3] Until the early 1990s, Argentina produced more wine than any other country outside Europe, though the majority of it was considered unexportable and was for internal consumption, as part of the typical Mediterranean diet installed in the country by the mass Italian and Spaniard immigration.[7] [4] [6][8] [9] However, the desire to increase exports fueled significant advances in quality. Argentine wines started being exported during the 1990s, and are currently growing in popularity, making it now the largest wine exporter in South America. The devaluation of the Argentine peso in 2002 further fueled the industry as production costs decreased and tourism significantly increased, giving way to a whole new concept of enotourism in Argentina.[citation needed]

The most important wine regions of the country are located in the provinces of Mendoza, San Juan and La Rioja. Salta, Catamarca, Río Negro and more recently southern Buenos Aires are also wine producing regions. The Mendoza province produces more than 60% of the Argentine wine and is the source of an even higher percentage of the total exports. Due to the high altitude and low humidity of the main wine producing regions, Argentine vineyards rarely face the problems of insects, fungi, molds and other grape diseases that affect vineyards in other countries. This allows cultivating with little or no pesticides, enabling even organic wines to be easily produced.[10]

There are many different varieties of grapes cultivated in Argentina, reflecting the country's many immigrant groups. The French brought Malbec, which makes most of Argentina's best known wines. The Italians brought vines that they called Bonarda, although Argentine Bonarda appears to be the Douce noir of Savoie, also known as Charbono in California. It has nothing in common with the light fruity wines made from Bonarda Piemontese in Piedmont.[11] Torrontés is another typically Argentine grape and is mostly found in the provinces of La Rioja, San Juan, and Salta. It is a member of the Malvasia group[citation needed] that makes aromatic white wines. It has recently been grown in Spain. Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Chardonnay and other international varieties are becoming more widely planted, but some varieties are cultivated characteristically in certain areas.[12]

In November 2010, the Argentine government declared wine as Argentina's national liquor.[1]

History

Viticulture was introduced to Argentina during the Spanish colonization of the Americas and later again by Christian missionaries. In 1556 father Juan Cedrón established the first vineyard in Argentina when cuttings from the Chilean Central Valley were brought to what is now the San Juan and Mendoza wine region, which firmly established viticulture in Argentina.[13] Ampelographers suspect that one of these cuttings brought the ancestor grape of Chile's Pais and California's Mission grape. This grape was the forerunner of the Criolla Chica variety that would be the backbone of the Argentine wine industry for the next 300 years.[14]

The first recorded commercial vineyard was established at Santiago del Estero in 1557 by Jesuit missionaries which was followed by expansion of vineyard plantings in Mendoza in the early 1560s and San Juan between 1569 and 1589. During this time the missionaries and settlers in the area began construction of complex irrigation channels and dams that would bring water down from the melting glaciers of the Andes to sustain vineyards and agriculture.[14] A provincial governor, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, instructed the French agronomist Miguel Aimé Pouget to bring grapevine cuttings from France to Argentina. Of the vines that Pouget brought were the very first Malbec vines to be planted in that country.[12]

As the early Argentine wine industry centralized in the western part of the country among the foothills of the mountains, the population centers of the country developed in the east. Transporting wine by means of a long wagon journey put a crimp in the growth of the wine industry that would not be eased till the 1885 completion of the Argentine railway that connected the city of Mendoza to Buenos Aires. Don Tiburcio Benegas, governor of the province of Mendoza and owner of El Trapiche wine estate, was instrumental in financing and pushing through the construction, convinced that in order for the Argentine wine industry to survive it needed a market.[15] The 19th century also saw the first wave of immigrants from Europe. Many of these immigrants were escaping the scourge of the phylloxera epidemic that ravaged vineyards in their homeland and they brought with them their expertise and winemaking knowledge to their new home.[14]

Economic troubles and growth of export industry

In the 20th century, the development and fortunes of the Argentine wine industry were deeply influenced by the economic influences of the country. In the 1920s, Argentina was the eighth richest nation in the world [citation needed] with the domestic market feeding [citation needed] a strong wine industry. The ensuing global Great Depression dramatically reduced vital export revenues and foreign investment and led to a decline in the wine industry.[citation needed]

There was a brief revival in the economy during the presidency of Juan Perón but the economy declined soon again under the military dictatorship of the 1960s and 1970s. During this time the wine industry was sustained by the domestic consumption of cheap vino de mesa. By the early 1970s, per capita consumption was nearly 90 L or 24 US gal (i.e. around 120 standard 750 mL wine bottles) per year, significantly more than many other countries including the United Kingdom[14] and United States which averaged around three liters (less than a gallon) per person during the same period.[10]

In the 1980s there was a period of hyperinflation, running at up to 12,000% per year in 1989.[16] Foreign investment was mostly stagnant. Under the presidency of Carlos Menem, the country saw some economic stability. The favorable exchange rate on the Argentine peso during the convertibility period saw an influx of foreign investment. However this period also saw a dramatic drop in domestic consumption.[14]

Following the example of neighboring Chile, the Argentine wine industry started to more aggressively focus on the export market—particularly the lucrative British and American markets. The presence of Flying winemakers from France, California and Australia brought modern technical know-how for viticultural and winemaking techniques such as yield control, temperature control fermentation and the use of new oak barrels. By the end of the 1990s, Argentina was exporting more 3.3 million gallons (12.5 million liters) to the United States with exports to the UK also strong. Wine experts such as Karen MacNeil noted that up to this point the Argentine wine industry was considered a "sleeping giant" which by the end of the 20th century was waking up.[10]

Climate and geography

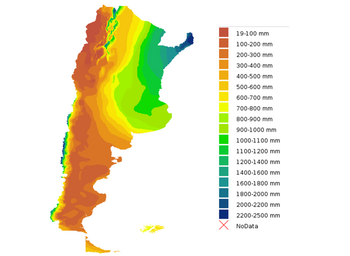

The major wine regions of Argentina are located in the western part of the country among the foothills of the Andes Mountains between the Tropic of Capricorn to the north and the 40th parallel south. Most of the regions have a semi-arid desert-like climate with annual rainfall rarely exceeding more than 250 mm (10 in) a year. In the warmest regions (such as Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan and the eastern outreaches of Mendoza), summer temperatures during the growing season can be very hot during the day with temperatures upwards of 40 °C (104 °F). Nighttime temperatures can drop to 10 °C (50 °F) creating a wide diurnal temperature variation.[14]

Some regions have more temperate climates such as the Cafayate region of Salta, Río Negro and the western reaches of Mendoza which includes the Luján de Cuyo and Tupungato departments. Wintertime temperatures can drop below 0 °C (32 °F) but frost is a rare occurrence for most vineyards, except those planted at extremely high altitudes with poor air circulation. Most rainfall occurs during the summer months and in late summer sometimes fall as hail (known as La Piedra), posing potential damage to the vines.[14] These warmer regions can see an average of 320 days of sunshine a year.[10]

The northwestern wine regions are particularly prone to the effects of the hurricane force winds known as the Zonda which blows from the Andes during the flowering period of early summer. This fierce wind of hot, dry air can disrupt the flowering process and severely reduce potential yields. Most of the growing season is dry with the lack of humidity limiting the risk and hazard from various grape diseases and fungal rot. Many vineyards operate without the need for any chemical spraying, a condition conducive to organic viticulture. The periodic occurrence of the El Niño phenomenon can have a sharp influence on climate condition during a growing season-such as the case during the 1998 vintage when prolong heavy rains brought by El Niño led to widespread rot and fungal disease.[14]

The Andes Mountains are the dominant geographical feature of Argentine wine regions, with the snow-capped mountains often serving as a backdrop view to the vineyards. As the winter snows start to melt in the spring, an intricate irrigation system of dams, canals and channels brings vital water supplies down to the wine regions to sustain viticulture in the dry, arid climates. Most of the wine regions are located within the foothills of the Andes and recent trends have seen a push to plant vineyards on higher elevations closer to the mountains.[12]

The climate in some of this regions can be more continental and less prone to extremes in temperatures. Soils throughout the country are mostly alluvial and sandy with some areas having substrates of clay, gravel and limestone. In the cooler Patagonia region which contains the winemaking provinces of Río Negro and Neuquén, the soil is more chalky.[14]

Viticulture

The growing season in Argentina usually last from budbreak in October to harvest beginning sometime in February. The Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura (INV), the main government controlling body for the wine industry, declares the beginning date for harvest in a region with the harvest season sometimes lasting till April depending on the variety and wine region. A sizable population of itinerant laborers provides an abundance of grape pickers at low cost which has slowed the conversion to mechanical harvesting. After harvest, grapes often have to be transported long distances, taking several hours, from the rural vineyards to winemaking facilities located in more urban areas. In the 1970s, yields were reported as surpassing 49 tonnes per hectare (22 short ton/acre), a sharp contrast to the average yields in premium wine regions such as Bordeaux and Napa Valley of 4 to 11 t/ha (2 to 5 short ton/acre).[10] As the Argentine wine industry continues to grow in the 21st century, several related viticultural trends will involve improvements in irrigation, yield control, canopy management and the construction of more winemaking facilities closer to the vineyards.[14]

Argentina is unique in the wine world for the absence of the phylloxera threat that has devastated vineyards across the globe. The phylloxera louse is present in Argentina but is a particular weak biotype that does not survive long in the soil. When it does attack vines, the damage is not significant enough to kill the vine and the roots eventually grow back.[2]

Because of this, most of the vineyards in Argentina are planted on ungrafted rootstock. There are many theories about why phylloxera has not yet reached this part of the world. The centuries-old tradition of flood irrigation where water is allowed to deeply saturate the soil may be one reason, as is the high proportion of sand present in the soil. The relative isolation of Argentina is also cited as a potential benefit against phylloxera with the country's wine regions being bordered by mountains, deserts and oceans that create natural barriers against the spread of the louse.[14] Despite the minimal risk of phylloxera, some producers are switching to grafted rootstock that provide better yield control.[10]

Various methods of vine training were introduced in Argentina by European immigrants in the 19th and 20th century. The espaldera system combined the traditional method of using three wires to train the vines close to the ground. In the 1950s a new system known as parral cuyano was introduced where vines were trained high off the ground with the clusters allowed to hang down.[12] This style was conducive to the high yielding varieties of Criolla and Cereza that were the backbone of the bulk wine production industry that arose in response to the large domestic market. In the late 20th century, as the market turned to focus more on premium wine production, more producers switched back to the traditional espaldera system and began to practice canopy management in order to control yields.[14]

Irrigation

The intricate irrigation system used to bring water from melted snow caps in the Andes originated in the 16th century (with the Spanish settlers adopting techniques previously used by the Incas[10]) and has been a vital component of agriculture in Argentina. Water flows down from the mountain through a series of ditches and canals where it is stored in reservoirs for use by vineyards which can apply for government-regulated water licenses that grant them access to the water. Newly planted vineyards on land that does not have existing water rights will often use alternative water sources such as drilling deep boreholes to 60–200 m (200–660 ft) below the surface to retrieve water from underground aquifer. These water wells, though costly to build, can supply a vineyard with as much as 250,000 liters (66,000 U.S. gallons) of water per hour.[14]

Historically, flood irrigation was the most common method used, whereby large amounts of water are allowed to run across flat vineyard lands. While this method may have been an unwittingly preventive measure against the advance of phylloxera, it does not provide much control for the vineyard manager to limit yields and increase potential quality in the wine grapes.[12] Subsequently, a method of furrow irrigation was developed whereby water is funneled into furrow channels that the vines are planted in. While providing a little more control, this method was still more suited to producing high yields. In the late 1990s, drip irrigation started to become more popular. Though expensive to install, this method provides for the maximum level of control by the vineyard manager to facilitate yield control and increase potential quality in the grape by leveraging water stress on the vine.[14]

Wine regions

While there is some wine production in the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and La Pampa, the vast majority of wine production takes place in the far western expanse of Argentina leading up to the foothills of the Andes. The Mendoza region is the largest region and the leading producer, responsible for more than two-thirds of the country's yearly production, followed by the San Juan and La Rioja regions to the north.

In the far northwestern corner of the country are the provinces of Catamarca, Jujuy and Salta which includes some of the world's highest planted vineyards. In the southern region of Patagonia, the Río Negro and Neuquén provinces have traditionally been the fruit producing centers of the country but have recently seen growth in the planting of cool climate varietals (such as Pinot noir and Chardonnay).[14]

Mendoza

Despite the total area planted declining from 629,850 to 360,972 acres (254,891 to 146,080 ha) between 1980 and 2003, Mendoza is still the leading producer of wine in Argentina.[14] As of the beginning of the 21st century, the vineyard area in Mendoza alone was slightly less than half of the entire planted area in the United States and more than the area of New Zealand and Australia combined.[10]

The majority of the vineyards are found in the Maipú and Luján departments. In 1993, the Mendoza sub region of Luján de Cuyo was the first controlled appellation established in Mendoza. Other notable sub-regions include the Uco Valley and the Tupungato department. Located in the shadow of Mount Aconcagua, the average vineyards in Mendoza are planted at altitudes 600 to 1,100 m (2,000 to 3,600 ft) above sea level. The soil of the region is sandy and alluvial on top of clay substructures and the climate is continental with four distinct seasons that affect the grapevine, including winter dormancy.[14]

Historically, the region has been dominated by production of wine from the high yielding, pink-skinned varieties of Cereza and Criolla Grande but in recent years Malbec has become the regions most popular planting. Cereza and Criolla Grande still account for nearly a quarter of all vineyard plantings in Mendoza but more than half of all plantings are now to premium red varietals which beyond Malbec include Cabernet Sauvignon, Tempranillo and Italian varieties. In the high altitude vineyards of Tupungato, located southwest of the city of Mendoza in the Uco Valley, Chardonnay is increasing in popularity.[14] The cooler climate and lower salinity in the soils of the Maipú region has been receiving attention for the quality of its Cabernet Sauvignon. Wine producers in the region are working with authorities to establish a controlled appellation.[2]

High-altitude plantings

Argentina's most highly rated Malbec wines originate from Mendoza's high altitude wine regions of Luján de Cuyo and the Uco Valley. These Districts are located in the foothills of the Andes mountains between 850 and 1,520 m (2,800 and 5,000 ft) elevation.[17][18][19][20]

Argentine vintner Nicolas Catena Zapata has been widely credited for elevating the status of Argentine Malbec and the Mendoza region through serious experimentation into the effects of high altitude.[21][22][23] In 1994, he was the first to plant a Malbec vineyard at almost 1,500 m (5,000 ft) elevation in the Gualtallary sub-district of Tupungato, the Adrianna Vineyard,[21][17] and to develop a clonal selection of Argentine Malbec.[24][25][26][21]

High altitude Mendoza has attracted many notable foreign winemakers such as Paul Hobbs, Michel Rolland, Roberto Cipresso and Alberto Antonini[17][18]

San Juan & La Rioja

After Mendoza, the San Juan region is the second largest producer of wine with over 47,000 ha (116,000 acres) planted as of 2003. The climate of this region is considerably hotter and drier than Mendoza with rainfall averaging 150 mm (6 in) a year and summer time temperatures regularly hitting 42 °C (108 °F). Premium wine production is centered on the Calingasta, Ullum and Zonda departments as well as the Tulum Valley.[12] In addition to producing premium red varietals made from Syrah and Douce noir (known locally as Bonarda), the San Juan region has a long history of producing sherry-style wines, brandies and vermouth. The high yielding Cereza vine is also prominent here where it is used for blending and grape concentrate as well as for raisin and table grape consumption.[14]

Recently, the higher-altitude vines planted in the Pedernal valley in Western San Juan, one of the most isolated regions in Argentina, have received significant acclaim for their potential to bring fame to the province's wine industry. The altitude here exceeds that of more southerly Uco Valley in Mendoza, leading to extremely dry conditions with high thermal amplitude and excellent results both for red and white wines.[27]

The La Rioja region was one of the first areas to be planted by Spanish missionaries and has the longest continued history of wine production in Argentina. Though a relatively small region, with only 8,100 ha (20,000 acres) planted as of 2003, the region is known for aromatic Moscatel de Alexandrias and Torrontés made from a local sub-variety known as Torrontés Riojano.[14] Lack of water has curtailed vineyard expansion here.[citation needed]

Northwestern regions

The vineyards of the northwestern provinces of Catamarca, Jujuy and Salta are located between the 24th parallel and 26th parallel south. They include some of the highest elevated vineyards in the world, with many planted more than 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level. Two vineyards planted by Bodega Colomé[28] in Salta are at elevations of 2,250 m (7,380 ft) and 3,000 m (9,800 ft). In contrast, most European vineyards are rarely planted above 900 m (3,000 ft). Wine expert Tom Stevenson notes that the habit of some Argentine producers to tout the altitude of their vineyards in advertisements and on wine labels as if they were grand cru classifications.[29]

The soils and climate of the regions are very similar to Mendoza but the unique mesoclimate and high elevation of the vineyards typically produces grapes with higher levels of total acidity which contribute to the wines balance and depth. Of the three regions, Catamarca is the most widely planted with more than 2,300 ha (5,800 acres) under vine as of 2003. In recent years the Salta region, and particularly its sub-region of Cafayate, have been gaining the most worldwide attention the quality of its full bodied whites made from Torrontés Riojano as well as its fruity reds made from Cabernet Sauvignon and Tannat.[14]

Most of Cafayate region in Salta is located at 1,660 m (5,450 ft) above sea levels in the river delta between the Rio Calchaqui and the Rio Santa Maria. The climate of the area experiences a foehn effect which traps rain producing cloud cover in the mountains and leaves the area dry and sunny. Despite its high altitude daytime temperatures in the summertime can reach 38 °C (100 °F) but at night the area experiences a wide diurnal temperature variation with night time temperatures dropping as low as 12 °C (54 °F). There is some threat of frost during the winter when temperatures can drop as low as −6 °C (21 °F). Despite producing less than 2% of Argentina's yearly wine production, the Cafayate region is increasing gaining in prestige and appearance on wine labels, as well as foreign investment from worldwide wine producers such as enologist Michel Rolland and California wine producer Donald M. Hess.[12]

Patagonia

The southern Patagonia region includes the fruit producing regions of Río Negro and Neuquén. These have a considerably cooler climate than the major regions to the north, which provides a long, drawn-out growing season in the chalky soils of the area. In the early 20th century, Humberto Canale imported vine cuttings from Bordeaux and established the first commercial winery in the region.[12] While 3,800 ha (9,300 acres) were planted as of 2003, the region is growing as more producers plant cool climate varietals like Chardonnay and Pinot noir as well as Malbec, Semillon and Torrontés Riojano. Many of the grapes for the Argentine sparkling wine industry are sourced from this area. Located more than 1,600 km (990 mi) south of Mendoza, the vineyards of Bodega Weinert are noted as the southernmost planted vineyards in the Americas.[14]

The most significant vineyards are located in the Rio Negro Valley, where some of the most prominent Pinot Noir red wines in Argentina are made, and in the upper Neuquen Valley, especially around the town of San Patricio del Chanar. Additionally, there are promising vineyards located in the La Pampa Province near the Colorado river, near the city of 25 de Mayo. These regions have shorter summers with longer daylight hours, and significantly colder winters than the main wine areas further north. Besides Pinot Noir, the area is known for producing good Merlot wines as well as white wines (mostly Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc). Recently, however, the area has gained traction because of its promising Cabernet Franc red wines, which have added to the diversity of Argentine wine with their hint of red fruit, elegant tannins and peppery taste. .[30]

Further south, the Province of Chubut is a mostly uncharted wine frontier. Traditionally considered too cold for plantings, there are micro-climates (e.g. the irrigated Chubut Valley area near the Atlantic coast, the Trevelin Valley where Pacific winds moderate the climate, and some steppe regions) which are promising for winemaking. Production started in the late 2000s, with a new Wine Route established in 2017. The main plantings have been, so far, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewürztraminer, Merlot, Riesling and Pinot Gris.[31]

New developments

Argentine winemakers have long held the belief that vines required hot and arid climates with large temperature variations to produce quality wines. This 'winning formula' led to a concentration of wineries in Mendoza, San Juan and La Rioja provinces in the west, as well as higher-altitude vineyards in Salta. More recently, there has been a shift towards slightly cooler and equally arid climates further south, in Neuquen and Rio Negro. Wineries there still benefit from windy and arid conditions, but with cooler temperatures and a shorter growing season.[citation needed]

However, in the last decade, the potential for 'non-traditional' (or re-discovered) regions has become apparent, concentrated in several areas: (1) the Atlantic coast from Mar del Plata (Buenos Aires) south and including the hills in Southern Buenos Aires, and (2) the mountains in Cordoba Province, which had been significant growers in colonial times, but where winemakers have only recently started experimenting with higher altitudes, (3) Entre Rios, an unlikely location because of its humid, warm climate, which had been famous for its wines more than a century ago, and (4) the Patagonian Plateau, a region of cold, windy and arid climates. Except for coastal Buenos Aires, where large investments are underway, most developments have consisted of smaller-scale wineries experimenting with new wine varieties and techniques, with the potential to bring about a completely 'new style' of Argentine wines which will be very different from the typical Malbec produced currently.[citation needed]

The climate in Mar del Plata and along the coast of Buenos Aires Province display the same temperature range as Bordeaux with similar (high) precipitation. Further inland, summers gain a few degrees while winter nights become somewhat colder in the flat southern Pampas. Adding to the variety of climates and soils in the area, there are low mountain areas (generally below 1,000 metres or 3,000 ft.), valleys and rivers. Major wineries (like Trapiche) have made investments in the area and production is likely to increase significantly, but most of the potential in this vast area is untapped. As the coast continues south, the weather becomes drier and windier, with (counter-intuitively) hotter summers. South of the city of Bahia Blanca, the Medanos area is becoming another focal point of the wine industry (see Buenos Aires wines. Weather records suggest that the coast should be adequate for wine making much further south: into Viedma, San Antonio Oeste, Puerto Madryn, Trelew and even Comodoro Rivadavia where cool, windy desert climates are greatly moderated by the Atlantic.[citation needed]

Climate chart for Mar del Plata:

| Climate data for Mar del Plata (1961–1990, extremes 1931–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.6 (106.9) |

38.2 (100.8) |

36.3 (97.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.7 (96.3) |

39.4 (102.9) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

6.4 (43.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 100.1 (3.94) |

72.8 (2.87) |

107.0 (4.21) |

73.3 (2.89) |

73.5 (2.89) |

54.9 (2.16) |

58.9 (2.32) |

64.0 (2.52) |

56.4 (2.22) |

83.4 (3.28) |

75.3 (2.96) |

104.0 (4.09) |

923.6 (36.36) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 107 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 77 | 79 | 81 | 83 | 84 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 77 | 76 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 288.3 | 234.5 | 232.5 | 195.0 | 167.4 | 120.0 | 127.1 | 164.3 | 174.0 | 210.8 | 222.0 | 269.7 | 2,405.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 63 | 60 | 54 | 58 | 51 | 41 | 42 | 46 | 47 | 51 | 52 | 59 | 52 |

| Source 1: NOAA,[32] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows), Oficina de Riesgo Agropecuario (June record low only) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (precipitation days),[33] UNLP (sun only)[34] | |||||||||||||

Climate of Bordeaux (for comparison - note the reverted seasons)

| Climate data for Bordeaux-Mérignac (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.4 (95.7) |

39.2 (102.6) |

38.8 (101.8) |

40.7 (105.3) |

37.0 (98.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.1 (80.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.4 (2.5) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 87.3 (3.44) |

71.7 (2.82) |

65.3 (2.57) |

78.2 (3.08) |

80.0 (3.15) |

62.2 (2.45) |

49.9 (1.96) |

56.0 (2.20) |

84.3 (3.32) |

93.3 (3.67) |

110.2 (4.34) |

105.7 (4.16) |

944.1 (37.17) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.2 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 11.9 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 124.3 |

| Average snowy days | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 3.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 84 | 78 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 75 | 76 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 88 | 80.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 96.0 | 114.9 | 169.7 | 182.1 | 217.4 | 238.7 | 248.5 | 242.3 | 202.7 | 147.2 | 94.4 | 81.8 | 2,035.4 |

| Source 1: Météo France[35][36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity and snowy days, 1961–1990)[37] | |||||||||||||

Another promising region are the Sierras de Cordoba in the middle of the country. Contrasting with the humid temperate Pampas, mountainous areas have better drainage, cooler nights and sunny weather. Historically, wine was grown in two areas: the Northern part of the province around Colonia Caroya and the extreme Western part, around Villa Dolores. These are the warmest, sunniest parts of the province and, in the past, produced sweet, lower quality wines (although new wineries are creating more interesting varietals).[38] The Eastern part of the Sierras, from the Villa General Belgrano area to the Punilla Valley, was generally considered to be too cool and humid, following the old Argentine stereotype of hot-desert wine-making. Over the last decade, however, boutique wineries have discovered the potential of the exceptional variety of soils and micro-climates in the area, producing wines that have won significant national awards (some near La Cumbrecita, an alpine town that would have been considered too cool for vines recently).[39] The scale of production remains minimal, but large numbers of new producers are experimenting with grape varieties and techniques to make wines that are significantly different from the stereotypical Mendoza Malbecs, often with great success. The large variation in elevation in the Sierras make them suitable for high-altitude wine experimentation, similar to what producers have done in Mendoza.[citation needed]

The Province of Entre Ríos has a warm, humid climate similar to neighboring Uruguay, where tannat wines are produced. Until the 1930s there were over 60 wineries in the Province, producing more wine than Mendoza and San Juan; these were however forbidden by law in an effort to ensure the settlement of Western Argentina. In recent years, over 60 producers have started replanting wines.[40]

Finally, the steppes of Central Patagonia in Chubut have the southernmost wines in the world. The climate here is markedly colder than any other region, with a threat of summer frost. Much longer summer days with very cold nights and a short growing season have the potential to produce wines that are markedly different from any other wines in Argentina.[41]

Grape varieties and wines

Under Argentine wine laws, if a grape name appears on the wine label, 100% of the wine must be composed that grape variety.[42] The backbone of the early Argentine wine industry was the high yielding, pink skin grapes Cereza, Criolla Chica and Criolla Grande which still account for nearly 30% of all vines planted in Argentina today. Very vigorous vines, these varieties are able to produce many clusters weighing as much as 9 pounds (4 kg) and tend to produce pink or deeply colored white wines that oxidize easily and often have noticeable sweetness.[14]

These varieties are often used today for bulk jug wine sold in 1 liter cardboard cartons or as grape concentrate which is exported worldwide with Japan being a considerably large market. In the late 20th century, as the Argentine wine industry shifted it focus on premium wine production capable for export, Malbec arose to greater prominence and is today the most widely planted red grape variety followed by Bonarda, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Tempranillo. The influence of Italian immigrants has brought a variety of Italian varietals with sizable plantings throughout Argentina-including Barbera, Dolcetto, Freisa, Lambrusco, Nebbiolo, Raboso and Sangiovese.[14]

While the historic birthplace of Malbec is Southwest France, where it is still widely grown in Cahors, and has some presence in Bordeaux, it is in Argentina where the grape receives most of its notoriety. The grape clusters of Argentine Malbec are different from its French relatives; they have smaller berries in tighter, smaller clusters.[2] Malbec wine is characterized by deep color and intense fruity flavors with a velvety texture.[10] As of 2003 there were over 20,000 ha (50,000 acres) of Malbec. The international variety of Cabernet Sauvignon is gaining in popularity and beside being made as a varietal, it used as a blending partner with Malbec, Merlot, Syrah and Pinot noir. Syrah has been steadily increasing in planting going from 700 ha (1,730 acres) in 1990 to more than 10,000 ha (24,710 acres) in 2003, with the San Juan region earning particular recognition for the grape. Tempranillo (known locally as Tempranilla) is often made by carbonic maceration (similar to Beaujolais); though some premium, old vine examples are made in the Uco Valley.[14] Red wine production accounts for nearly 60% of all Argentine wine. The high temperatures of most regions contribute to soft, ripe tannins and high alcohol levels.[2]

The Pedro Giménez grape (a different but perhaps closely related relative of Spain's Pedro Ximénez) is the most widely planted white grape varietal with more than 14,700 ha (36,300 acres) planted primarily in the Mendoza and San Juan region. The grape is known for its fully bodied wines with high alcohol levels and is also used to produce grape concentrate. The next largest plantings are dedicated to the Torrontés Riojano variety followed by Muscat of Alexandria, Chardonnay, Torrontés Sanjuanino (the sub-variety of Torrontés that is believed to have originated in the San Juan province) and Sauvignon blanc. Other white grape varieties found in Argentina include Chenin blanc, Pinot gris, Riesling, Sauvignonasse, Semillon, Ugni blanc and Viognier.[14]

Torrontés produces some of the most distinctive white wines in Argentina, characterized by floral Muscat-like aromas and a spicy note.[10] The grape requires careful handling during the winemaking process with temperature control during fermentation and a sensitivity to certain strains of yeast. The grape is most widely planted in the northern provinces of La Rioja and Salta, particularly the Calchaquí Valleys, but has spread to Mendoza. In response to international demand, plantings of Chardonnay have steadily increased. The University of California, Davis produced a special clone of the variety (known as the Mendoza clone) that, despite it propensity to develop millerandage, is still widely used in Argentina and Australia. Argentine Chardonnay has shown to thrive in high altitude plantings and is being increasing planted in the Tupungato region on vineyard sites located at altitudes around nearly 1,200 m (3,900 ft).[14]

Modern wine industry

By the turn of the 21st century there were over 1,500 wineries in Argentina. The two largest companies are Bodegas Esmeralda (which owns the widely exported brand Alamos) and Peñaflor (which owns another widely exported brand Bodegas Trapiche). Between the two of them, these companies are responsible for nearly 40% of all the wine made in Argentina. The Argentine wine industry is fifth worldwide in production and eighth in wine consumption.[10]

The continued trend of the industry is to increase quality and control yields. Between the mid-1990s and early 21st century, Argentina had ripped up nearly a third of its vineyards but reduced yearly production only by 10%. This meant there was an increase in yields from 66 hl/ha to 88 hl/ha.[29]

See also

References

- ^ a b Ley No. 26870 – Declárase al Vino Argentino como bebida nacional, 2 de agosto de 2013, B.O., (32693), 1 (in Spanish)

- ^ a b c d e H. Johnson & J. Robinson: The World Atlas of Wine, pp. 300-301, Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4.

- ^ a b Stein, Stephen. ""Lots of Wine, Very Quickly, Very Badly:" European Immigrants and the Making of Argentina's Wine Industry". Bridge to Argentina. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ a b "La influencia de los italianos en la industria vinícola argentina". Italianos en Argentina (in Spanish). 2023-05-22. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ a b Stein, Stephen (2023). "Making Wine for the People's Taste: The Emergence of the Argentine Wine Industry, 1885–1915". Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. 33 (2): 89–113. doi:10.7202/1108199ar.

- ^ a b Portelli, Por Fabricio (2023-11-24). "Cómo el vino se convirtió en la bebida nacional argentina: 10 etiquetas para celebrar su día". infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ Robinson, Jancis (July 13, 2007). "Chile v Argentina - an old rivalry". Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ "Origen del primer vino argentino: Descubre su historia" (in Spanish). 2024-06-26. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "Tomar un vino de... 1940. Crece la costumbre de guardar vino y el gusto por las botellas añejas". LA NACION (in Spanish). 2024-05-15. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pp. 848-857. Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- ^ Robinson, Jancis (September 9, 2008). "Argentina". Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h A. Domine (ed): Wine pp. 840-844. Ullmann Publishing 2008 ISBN 978-3-8331-4611-4.

- ^ "The History of Wine in Argentina". Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition, pp. 29-33. Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ H. Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine pp. 434 Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ New York Times: THE WORLD; For Argentina, Inflation and Rage Rise in Tandem, 4 June 1989

- ^ a b c Catena, Laura (September 2010). Vino Argentino, An Insiders Guide to the Wines and Wine Country of Argentina. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-7330-7.

- ^ a b Rolland, Michel (January 2006). Wines of Argentina. Mirroll. ISBN 978-987-20926-3-4.

- ^ Wine Tip: Malbec Madness, "Wine Spectator", April 12, 2010.

- ^ Tim Atkin: Uco Valley Archived 2018-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, "Tim Atkin: Uco Valley ".

- ^ a b c Julio Elías, Gustavo Ferro, and Alvaro Garcia, 2019."A Quest for Quality: Creativity and Innovation in the Wine Industry of Argentina" Asociación Argentina de Economía Política: Working Papers 4135.

- ^ Pierre-Antoine Rovani's Wine Personalities of the Year Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Parker Jr.’s The Wine Advocate Issue 156 - December 2004, August 27, 2009.

- ^ The Might of Mendoza: the romantic tale behind Argentina's booming malbec grape, The Independent UK, June 2014.

- ^ Catena malbec 'Clone 17', PatentStorm.us, August 27, 2009. Archived October 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nicolás Catena Such Great Heights, Gismondi, Anthony Montecristo Magazine, November 7, 2014.

- ^ Four Magazine Archived 2016-12-27 at the Wayback Machine, Wine Spectator, 2012.

- ^ Wines of Argentina, Pedernal. URL: http://blog.winesofargentina.com/es/pedernal-valley-the-extreme-wines-of-san-juan/

- ^ Bodega Colomé - Historia. Archived 2021-03-03 at the Wayback Machine bodegacolome.com. Retrieved 7 March 2021

- ^ a b T. Stevenson "The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia" p. 545; Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8.

- ^ Wines of Argentina. URL: http://www.winesofargentina.org/argentina/regiones/patagonia/

- ^ La Ruta del Vino en Chubut. URL: http://www.infobae.com/turismo/2017/03/17/la-ruta-del-vino-en-chubut-un-viaje-para-potenciar-todos-los-sentidos/

- ^ "Mar del Plata AERO Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "Valores Medios de Temperature y Precipitación-Buenos Aires: Mar del Plata" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "Datos bioclimáticos de 173 localidades argentinas". Atlas Bioclimáticos (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ "Données climatiques de la station de Bordeaux" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Climat Aquitaine" (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Bordeaux-Merignac (33) - altitude 47m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Mariano Braga Wine Strategist | URL: http://www.marianobraga.com/blog/cordoba-vino-argentina-traslasierra/.

- ^ Prensa de la Provincia de Cordoba | URL: http://prensa.cba.gov.ar/campo/vino-cordobes-gano-premio-internacional/ Archived 2019-12-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Manera, Marcelo (5 August 2016). "Entre Ríos, una zona que vuelve a apostar por el vino" [Between rivers, a zone that bets on the return of wine]. La Nacion: Vino del Parana (in Spanish). Grupo de Diarios América. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Gualjaina elaborara vinos de calidad, Diario La Jornada, URL: http://www.diariojornada.com.ar/182759/sociedad/gualjaina_bodega_elaborara_vinos_de_calidad/.

- ^ Kevin Zraly (2018). Kevin Zraly Windows on the World Complete Wine Course. Sterling Epicure. ISBN 978-1454930464.