Aden Colony

Aden Colony مُسْتْعَمَرَةْ عَدَنْ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937–1963 | |||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||

Map of Aden Colony and its dependencies in red | |||||||||

Map of Aden Colony | |||||||||

| Status | Crown colony of the United Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Aden 12°48′N 45°02′E / 12.800°N 45.033°E | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Adenese | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1937–1952 | George VI | ||||||||

• 1952–1963 | Elizabeth II | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1937–1940 | Sir Bernard Reilly | ||||||||

• 1960–1963 | Sir Charles Johnston | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Aden Settlement established | 1839 | ||||||||

• Aden Colony established | 1937 | ||||||||

• State of Aden established | 18 January 1963 | ||||||||

• State of Aden disestablished | 30 November 1967 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1955 | 138,230[1] | ||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Yemen |

|---|

|

|

Aden Colony (Arabic: مُسْتْعَمَرَةْ عَدَنْ, romanized: Musta'marat 'Adan) was a crown colony of the United Kingdom from 1937 to 1963 located in the southern part of modern-day Yemen. It consisted of the port city of Aden and also included the outlying islands of Kamaran, Perim and the Khuria Muria archipelago with a total area of 192 km2 (74 sq mi). Initially a key port for the British East India Company, it was annexed by the British in 1839 to secure maritime routes and prevent piracy in the Arabian Sea. Its strategic position at the entrance to the Red Sea made it a vital stopover for ships traveling between Europe, India, and the Far East, especially after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Aden quickly became a major coaling station and transit hub for British shipping, and its significance to the British Empire grew throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Prior to 1937, Aden had been governed as part of British India (originally as the Aden Settlement subordinate to the Bombay Presidency, and then as a Chief Commissioner's province). In 1 April 1937, Aden was separated from British India to become a Crown colony under the Government of India Act 1935, consisting of the city of Aden and its surrounding areas. The colony experienced rapid development due to its thriving port, but it was also marked by growing civil unrest. Economic inequality, labor strikes, and the rise of Arab nationalism contributed to increasing tensions, which were intensified by the anti-colonial sentiment in the Middle East. During this period, Aden became important for British military and commercial purposes in the region, as well as a base for the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. The colony's surrounding hinterland, was governed separately as the Aden Protectorate.

By the early 1960s, widespread dissatisfaction with British rule led to the Aden Emergency, a violent uprising against colonial authorities. In 1963, Aden Colony was reconstituted as the State of Aden within the newly created Federation of South Arabia in an attempt to grant limited self-governance, but the unrest continued. The British withdrew in 1967, and the colony was succeeded by the People's Republic of Southern Yemen, marking the end of British control after 128 years of rule.

History

On 18 January 1839, the British East India Company landed Royal Marines at Aden. Their aims were to establish a supply port and stop attacks by Arab pirates against British shipping to India. The British Government thereafter considered Aden to be an important settlement due to its location, as the Royal Navy could easily access the port for resupply and repairs.[2] Later, British influence extended progressively into the hinterland, both west and east, leading to the establishment of the Aden Protectorate.

Aden soon became an important transit port and coaling station for trade between British India and the Far East, and Europe. The commercial and strategic importance of Aden increased considerably when the Suez Canal opened in 1869. From then and until the 1960s, the Port of Aden was to be one of the busiest ship-bunkering, duty-free shopping, and trading ports in the world.[3]

In 1937, Aden was separated from British India to become a Crown colony, a status that it retained until 1963. It consisted of the port city of Aden and its immediate surroundings (an area of 192 km2 [74 sq mi]). The Aden Settlement, and later Aden Colony, also included the outlying islands of Kamaran (de facto),[4] Perim and Kuria Muria (see map).

Prior to 1937, Aden had been governed as part of British India (originally as the Aden Settlement under the Bombay Presidency, and then as a Chief Commissioner's province). Under the Government of India Act 1935 the territory was detached from British India, and was re-organised as a separate Crown colony of the United Kingdom; this separation took effect on 1 April 1937.[citation needed]

Through the latter years of its existence, Aden Colony was plagued by civil unrest.

Elizabeth II visit

| External videos | |

|---|---|

On 27 April 1954, Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh visited the colony as part of their first Commonwealth tour.[a][6][7] They were greeted by Governor of Aden Tom Hickinbotham and travelled to an enclosure to watch a military parade which included the RAF, Aden Protectorate Levies, Armed Police, Government Guards, the Hadhrami Bedouin Legion, and Somaliland Scouts.[7]

The visit saw Aden hold its first and only knighthood ceremony in which local leader Sayyid Abubakr bin Shaikh Al-Kaff was knighted whilst kneeling on a chair instead of bowing due to his Muslim faith.[8][9] The Queen also knighted Claude Pelly, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Air Force in the Middle East.[7]

A bronze plaque marks the foundation stone Elizabeth II laid for Al Jumhuriyah hospital during the visit.[7] The hospital which was originally named after her until the end of British rule in 1967 was bombed by the Houthi movement in 2015, but remains open due to a UAE-funded restoration project.[7][10]

Administration

The fundamental law for the Crown colony of Aden was the Order of Council 28 September 1936, which follows the usual lines of basic legislation for British colonies. The town of Aden was noted as being tied "much more closely into the fabric of the British Empire", with a faster rate of development, than the area surrounding it.[11]

Aden was notable in that sharia law was not used in the colony. "All suits, including those dealing with personal status and inheritance of Muslims, are entertained in the ordinary secular courts of the colony".[12]

Within Aden Colony, there were three local government bodies. The Aden municipality, which covered the town, Tawali, Ma'alla and Crater, the Township authority of Sheikh Othman and finally Little Aden had been established in recent years as a separate body, covering the oil refinery and the workers' settlement. All of these bodies were under the overall control of the Executive Council, which in turn was kept in check by the Governor.

Until 1 December 1955, the Legislative Council was entirely unelected. The situation improved only slightly after this date, as four members were elected.[13] Judicial administration was also entirely in British hands. "Compared with other British possessions, the development towards self-government and greater local participation has been rather slow".[13]

Education was provided for all children, both boys and girls, until at least intermediate level. Higher education was available on a selective basis through scholarships to study abroad. Primary and Intermediate education was conducted in Arabic while Secondary and independent schools conducted their lessons in Arabic, English, Urdu, Hebrew and Gujarati. There were also Quranic schools for both boys and girls, but these were unrecognised.[14]

Economy and finances

After 1937, the economy of Aden continued to be largely dependent on the city's role as an entrepôt for east–west trade. During the course of 1955, 5239 vessels called at Aden, making its harbour the second busiest in the world after New York.[15] However, tourism declined over the last years of the Colony with the number of tourists landing dropping by 37% from 204,000 in 1952 to 128,420 in 1966. At the end of British rule in 1967, the main revenues of the Colony were the Port Trust with an annual gross revenue of £1.75 million (2014 prices: £28.4 million) and the British Petroleum refinery which made direct payments to the Aden Government of £1.135 million (2014 prices: £18.4 million).[16]

In 1956, Aden Colony had a revenue of £2.9 million (approximately £65 million in 2014 prices). This was equivalent to around £58 per capita, one of the highest per head revenue earners amongst Britain's smaller colonies behind only the Falkland Islands, Brunei and Bermuda.[17] However, the benefit to the United Kingdom of this was tempered by their commitments to the Aden protectorates which had revenue per capita of only 2.5 pence (only 23p in 2014 prices).

By the time British rule was ending the Federation of South Arabia, of which the Colony was a part, was receiving £12.6 million (£209 million in 2014) from the British government to support its 1966–67 Budget.[18]

Demographics

The colony's population was 80,516 in the census of 1946;[19][20] in its second census in 1955, the total had risen to 138,230.[1]

| Arabs | Somalis | Jews | Indians | Europeans | Miscellaneous | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103,879 | 10,611 | 831 | 15,817 | 4,484 | 2,608 | 138,230 |

The 1955 census enumerated the colony's 103,879 Arabs as Aden Arabs (36,910), Protectorate Arabs (18,881) and Yemeni Arabs (48,088).[1] The European population consisted of 3,763 British (including military) and 721 other Europeans.[1] The colony's Somali population predated the arrival of the British in Aden.[21] The colony's Jewish population (qv.) had been over 7,000 in 1946,[19] but dropped following the removal of most Jews to the new state of Israel in Operation Magic Carpet.

The colony's estimated population grew to well over 200,000 in the 1960s.

Domestic issues

Labour movements, trade unions and internal dissent

Trade unions formed the basis for most of the outlet of social dissatisfaction in Aden. The first union, the Aden Harbour Pilots Association, had been formed in 1952,[22] quickly followed by two more by the end of 1954. By 1956 most trades had formed a Union. There had been an assumption that the British model of Trade Union development would be followed.[23] However, in the local tangle of grievances, the nationalist and economic were difficult to differentiate. As a result, strikes and demonstrations were often politically motivated, rather than by purely economic reasons.

The British Army returned to Aden in July 1955 after Yemeni-armed rebel tribesmen caused disturbances.[24] Minor events continued into early 1956, when a British assistant adviser to part of the Western Aden Protectorate was wounded in a rebel ambush.[25]

On the 19 March 1956, labourers at the Little Aden refinery went on strike. Workers stoned policemen at the refinery gates, with clashes resulting in some deaths.[26] The strike lasted ten days, being called off on the 29 March, with agreement reached mainly on pay.[27] The strikes in 1956 were marked by a good many attacks on non-Arab groups. It was during this time that the Army took over command of Aden from the Royal Air Force, with its presence maintained "in view of the importance of preserving internal security" according to War Secretary Antony Head.[28] Days after the strike had ended, the Governor Sir Tom Hickinbotham conferred with almost all of the tribal leaders from the Aden Protectorates, where broad agreement was reached that they should "seek some form of close association with each other".[29]

In May 1958 a state of emergency was declared and there were a number of bombings until the arrest of the principal instigators in July. However, in October 1958 there was a general strike, which was accompanied by widespread rioting and disorder which ended in the deportation of 240 Yemenis from Aden, as claimed by author Gillian King: "By ignoring the views of the local labour force, the British pushed much of the Arab population into opposition against their rule, who previously had been by no means captivated by Nasser".[30]

At the time much of the blame for these disturbances was placed on the broadcasts from Radio Cairo encouraged by Nasser's anti-imperialist and Arab Nationalist regime there, as claimed by author R. J. Gavin: "Radio Cairo began to speak in the tones of revolutionary Arab Nationalism. Men who had long lived in isolation now found a common political language and a breathtaking, liberating community of sentiment across the Arab world".[31]

In December 1963 there was a grenade attack by an unidentified assailant on the high commissioner who was unharmed; however, three bystanders were killed.

Jews in Aden

There had been Jewish tribes in Aden and Yemen for millennia,[32] where they had primarily constituted the artisans and craftsmen of these areas, but it was after the British occupation of 1839 that Aden became an important congregation.

During the two World Wars the Jews in Aden had prospered while those in Yemen suffered.[33] The Balfour declaration had encouraged increased Jewish immigration into the Holy Land, and as a result many of the Jewish communities from all over the Middle East sought a new home there. The Palestine issue had a serious effect on British prestige in Aden.[citation needed]

During the Second World War, Jews from Yemen flocked in large numbers into Aden while en route to Palestine, where they were placed in refugee camps, primarily for their own safety. However conditions in the camps were difficult and in 1942 there was an outbreak of Typhus. The need for the camps was apparent when in December 1947, following the UN declaration for the creation of a Jewish state, there were serious riots in Aden Town, where at least 70 Jews were killed and much of the Jewish Quarter was burnt and looted. Until this point nearly all the refugees had been from Yemen and the Aden Protectorate, but now after the growing violence against Jews in the Town itself, most tried to leave. This was shown by the population figures which from a high of roughly 4,500 in 1947 less than 500 were left in 1963. "The 1947 incident found Government policies at odds with the whole Arab community, including those who manned the police forces".[34]

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War made immigration into Israel very difficult, as the Red Sea and Suez Canal were closed by the Egyptian government. By 1949 and after the declaration of a cease fire, 12,000 Jews from Yemen, Aden and the Protectorate were gathered in camps, from where they were airlifted on average 300 a day to Israel, in Operation Magic Carpet.

Foreign policy issues

Aden was located in a vital strategic location, on the main shipping routes between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. During the days of Empire, the value of the port was in providing key communications and bunkering facility between the Suez Canal and India. Even after the independence of India, Aden continued to be regarded as a vital asset in Britain's worldwide defence network.[35] By 1958, Aden was the second-busiest harbour in the world, after New York City, described as having importance that "cannot be overestimated" while protecting British oil interests in the region.[36] The Little Aden oil refinery was essential to the economy of Aden as it could process 5 million tons of crude oil annually and formed one of the Colony's only exports. The safety of this refinery was a clear priority for the government of Aden.[37]

"As a temporary expedient, the Aden base has the merits of a stabiliser at a moment when the Yemen is split by civil war, when the Saudi Royal house has not yet made itself a name for consistent rule, when the Iraqi and Syrian governments are prone to overnight revolutions and when Egypt's relations with both of them are uncertain".[38]

For much of Aden's later history, relations with the United Arab Republic (UAR) were of primary consideration. Its 1958 establishment was described as having "increased the importance of Aden as a British military base in this troubled corner of the world".[39] However even before the formation of the UAR, Arab nationalism had been growing in the awareness of Adeni's. "In 1946, Students protested that the anniversary of the founding of the Arab league had not been made a public holiday".[40]

The most serious problem facing Aden in the late 50s and 60s was the relationship with the Yemen and Yemeni raids along the borders. But the adherence of Yemen to the UAR created a delicate situation and several political problems arose. Immigration into the Colony was a major concern of the local Arab workforce.

Previously to the creation of the UAR, peace in Aden it was admitted came not from the presence of the tiny garrison, but from a lack of Arab poles of attraction for malcontents.

However some contemporary writers, such as Elizabeth Monroe thought that the British presence in Aden may have been self-defeating, as it provided a casus belli for Arab nationalists. So rather than supporting British peace efforts in the region, Aden was actually the cause of much anti-British sentiments in the region.

"As in Kuwait prosperous older men appreciate the advantages of the British connection, but young Arab nationalists and a vigorous trade union movement think it humiliating".[41]

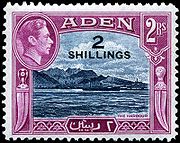

Monetary system in Aden

Being an extension of British India, the British Indian rupee was the currency of Aden until shortly after India gained independence in 1947. In 1951, the rupee was replaced by the East African shilling which was on par with the shilling sterling. Then with the advent of the South Arabian Federation, a new South Arabian dinar was introduced in 1965 which was on par with the pound sterling. The South Arabian dinar was a decimal unit divided into fils.

Aden became independent as the South Yemen on 30 November 1967 without joining the Commonwealth, but the South Arabian dinar continued at the one-to-one parity with sterling until 1972. In June 1972, the British Prime Minister Edward Heath unilaterally reduced the sterling area to include only the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands and Ireland (and Gibraltar the following year).[42][43]

The South Yemen reciprocated immediately by introducing its own exchange controls and ending the fixed peg to sterling. South Yemen was still however listed in British law as being part of the overseas sterling area, that being a list of scheduled territories which continued to enjoy some exchange control privileges with the United Kingdom right up until 1979 when Geoffrey Howe abolished all United Kingdom exchange controls.

Federation and the end of Aden colony

To solve many of the above problems, as well as continuing the process of self-determination that was accompanying the dismantling of the Empire, it was proposed that Aden Colony should form a federation with the protectorates of East and West Aden. It was hoped that this would lessen Arab calls for complete independence, while still allowing British control of foreign affairs and the BP refinery at Little Aden to continue. It was the hope of the government of Harold Macmillan that creating a federation that would be dominated by the traditional sultans would allow for indirect British control as he wrote in his diary that his government planned to use "the Sultans to help us keep the colony and its essential defence facilities".[44] However, the population of Aden was urban, well educated, secular and generally left-wing while the population of the protectorates were rural, mostly illiterate, religious and generally conservative, making the proposed federation a mismatch.[44]

Federalism was first proposed by ministers from both the colony and protectorates, the suggested amalgamation would be beneficial they argued, in terms of economics, race, religion and languages. However the step was illogical in terms of Arab Nationalism, for it was taken just prior to some impending elections, and was against the wishes of Aden Arabs, notably many of the trade unions. An additional problem was the huge disparity in political development, as at the time Aden colony was some way down the road to self-government and in the opinion of some dissidents, political fusion with the autocratic and backward Sultanates was a step in the wrong direction. In the federation, Aden colony was to have 24 seats on the new council, while each of the eleven sultanates was to have six. While the federation as a whole would have financial and military aid from Britain. The federation was opposed by the majority of the people of Aden, leading to a series of strikes and protest marches while the elections for the council were rigged in favour of supporters of the federation.[45] Right from start, the federation was seen as illegitimate.[46]

On 18 January 1963, the colony was reconstituted as the State of Aden (Arabic: ولاية عدن Wilāyat ʿAdan), within the new Federation of South Arabia. With this Sir Charles Johnston stepped down as the last Governor of Aden.

Many of the problems that Aden had suffered in its time as a colony did not improve on federation. Internal disturbances continued and intensified, leading to the Aden Emergency and the final departure of British troops. British rule ended on 30 November 1967.

The federation became the People's Republic of Southern Yemen, and in line with other formerly British Arab territories in the Middle East, it did not join the Commonwealth of Nations.

Governors of Aden colony

- Sir Bernard Rawdon Reilly (1 April 1937 – 24 October 1940)

- John Hathorn Hall (24 October 1940 – 1 January 1945) (From 2 December 1940, Sir John Hathorn Hall)

- Reginald Stuart Champion (1 January 1945 – 1950) (From 1 January 1946, Sir Reginald Stuart Champion)

- William Allmond Codrington Goode (1950 – April 1951) (Acting)

- Sir Tom Hickinbotham (April 1951 – 13 July 1956)

- Sir William Luce (13 July 1956 – 23 October 1960)

- Sir Charles Johnston (23 October 1960 – 18 January 1963)

Chief Justices of Aden Colony

- James Taylor Lawrence (1938–1942; died 1944)

- Charles Theodore Abbott (1940–41; acting and afterwards in Federation of Malaya)

- Geoffrey Barkitt Whitcombe Rudd (1944; acting and afterwards in Kenya)

- Ronald Knox-Mawer (1952; acting and afterwards in Fiji)

- Ralph Abercrombie Campbell (1956–1960; afterwards Chief Justice of the Bahamas, 1960)

- Richard Lyle Le Gallais (1960–1963)

See also

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Reginald Sorensen. "Aden, the Protectorates and the Yemen." Fabian Tract 332. Fabian International and Commonwealth Bureaux, 1961. p. 12.

- ^ "Port of Aden from the Sea". World Digital Library. December 1894. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Port of Aden".

- ^ Kamaran was Turkish until 1915 and served as a quarantine station for Muslims on the pilgrimage to Mecca. The British captured Kamaran in 1915 and, since they could not come to an agreement with the Imam of Yemen who claimed the island, they continued to occupy the 108 km2 (42 sq mi) island without a clear title to it until it was handed over to the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) in 1967. Some pictures of Kamaran in 1954: "British-Yemeni Society: The island of two moons: Kamaran 1954". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ Chris Cook and John Paxton, Commonwealth Political Facts (Macmillan, 1978).

- ^ "Commonwealth visits since 1952". Official website of the British monarchy. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Mahmood, Ali (2 June 2022). "Platinum Jubilee: Yemen remembers Queen Elizabeth's visit and a lost era of hope". The National. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023.

- ^ Noman, Alaa; Magdy, Samy (17 September 2022). "In Yemen, Queen Elizabeth's death recalls memories of Britain's colonial rule". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023.

- ^ Al-Shamahi, Abubakr (9 September 2022). "Queen Elizabeth II's last foothold in Arabia". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023.

- ^ Salman, Fawaz (15 September 2022). "In once flourishing Aden, Yemeni matriarch recalls British queen's visit". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023.

- ^ H. J. Liebensy. Administration and Legal Development in Arabia. Middle East Journal 9. 1955. p. 385.

- ^ H. J. Liebensy. "Administration and Legal Development in Arabia", Middle East Journal (1955), p. 385.

- ^ a b E. H. Rawlings. The Importance of Aden. Contemporary Review 195. 1959. p. 241.

- ^ Colonial Reports. Aden Report. p. 37

- ^ Colonial Office List, 1958 (London, HMSO, 1958), cited in Spencer Mawby, British Policy in Aden and the Protectorates, 1955–1967, Last Outpost of a Middle East Empire, London, Routledge, 2005, p. 14.

- ^ 'Aden port faced by staff crisis', The Times, March 22, 1967

- ^ The Times Friday, May 25, 1956

- ^ The Times, June 10, 1966

- ^ a b R. J. Gavin. Aden Under British Rule 1839–1967. C. Hurst & Co., 1975. p. 445. ISBN 9780903983143

- ^ Report on Aden and Aden Protectorate for the Year 1946. Colonial Annual Reports. His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1948. p. 12.

- ^ Edward A. Alpers. "The Somali Community at Aden in the Nineteenth Century." Northeast African Studies. 8:2/3 (1986). p. 143. JSTOR 43660375

- ^ Colonial Reports. Aden Report 1953&54. HM Stationery Office 1956.

- ^ D. C. Watt. Labour relations and Trade Unionism in Aden 1952–60.

- ^ The Times Wednesday, Mar 28, 1956

- ^ The Times Tuesday, Feb 21, 1956

- ^ The Times Wednesday, Mar 21, 1956

- ^ The Times Saturday, March 31, 1956

- ^ The Times Wednesday, March 28, 1956

- ^ The Times Monday, April 02, 1956

- ^ Gillian King. Imperial Outpost-Aden - Its Place In British Strategic Policy. Chatham House Essay Series. 1964. p.323

- ^ R. J. Gavin. Aden Under British Rule 1839–1967. p.332

- ^ Montville, Joseph V. (2011). History as Prelude: Muslims and Jews in the Medieval Mediterranean. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739168141.

- ^ N. Bentwich. "The Jewish Exodus from Yemen and Aden." Contemporary Review, 177. 1950. p. 347

- ^ R. J. Gavin. Aden Under British Rule. p.323.

- ^ Gillian King. Imperial Outpost-Aden. Chatham House Essay Series. 1964

- ^ E. H. Rawlings, Contemporary review 195. 1955. p. 241.

- ^ Spencer Mawby. British Policy in Aden and the Protectorates 1955–67: Last Outpost of a Middle East Empire.

- ^ Elizabeth Monroe. Kuwayt and Aden. p. 73.

- ^ E. H. Rawlings. The Importance of Aden. Contemporary Review 195. 1959. p. 241.

- ^ R. J. Gavin. Aden Under British Rule. p. 325.

- ^ Elizabeth Monroe. Kuwayt and Aden. p. 70.

- ^ Schmitthoff, Clive Macmillan; Cheng, Chia-Jui (1937), Clive M. Schmitthoff's select essays on international trade law (reprint ed.), BRILL, p. 390, ISBN 978-90-247-3702-4

- ^ Belchem, John (2000), A New History of the Isle of Man: The modern period 1830–1999, Liverpool University Press, p. 270, ISBN 978-0-85323-726-6

- ^ a b Newsinger 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Newsinger 2012, p. 115-116.

- ^ Newsinger 2012, p. 116.

General references

- Colonial Reports. Aden Report: 1953 & 1954, HM Stationery Office 1956.

- Paul Dresch. A History of Modern Yemen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- R.J. Gavin. Aden Under British Rule: 1839–1967. London: C. Hurst & Company, 1975.

- Gillian King. Imperial Outpost: Aden: Its Place in British Foreign Policy. Chatham House Essay Series, 1964.

- H. J. Liebensy. Administration and Legal Development in Arabia. Middle East Journal, 1955.

- Tom Little. South Arabia: Arena of Conflict. London: Pall Mall Press, 1968.

- Elizabeth Monroe. Kuwayt and Aden: A Contrast in British Policies. Middle East Journal, 1964.

- Newsinger, John (2012). British Counterinsurgency. London: Springer. ISBN 978-1137316868.

- E. H. Rawlings. The Importance of Aden. Contemporary Review, 195, 1959.

- Jonathan Walker. Aden Insurgency: The Savage War in South Arabia 1962–67, Spellmount, 2004.

- D. C. Watt. Labour Relations and Trade Unionism in Aden: 1952–60. Middle East Journal, 1962.

Further reading

- Schaefer, Charles (1999). "'Selling at a Wash:' Competition and the Indian Merchant Community in Aden Crown Colony". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 19 (2): 16–23. doi:10.1215/1089201X-19-2-16.