1799 Vendée earthquake

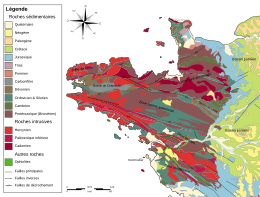

The Marais breton-vendéen is situated in the Vendéen zone of the south west Armorican Massif, to the east of the island of Noirmoutier. Its bedrock comprises Quaternary sedimentary rocks.[1] | |

| UTC time | 1799-01-25 03:00 |

|---|---|

| Local date | January 25, 1799 |

| Local time | 04:00 CET |

| Magnitude | 6.5 |

| Depth | 24 km (15 mi) |

| Epicenter | 46°57′34″N 2°05′32″W / 46.959313°N 2.092153°W |

| Max. intensity | MMI VIII (Severe) |

| Tsunami | not recorded but probable |

| Aftershocks | until 6 February 1799 |

The 1799 Vendée earthquake (French: Séisme de 1799 dans le Marais breton-vendéen) or Bouin earthquake was a magnitude 6.4 earthquake that struck the Vendée area of western France on 25 January 1799 (6 Pluviôse of year VII in the French Republican calendar) with aftershocks on the following days. Its epicenter was located at a depth of 24 km in the Bay of Bourgneuf at the level of the island of Bouin. Shocks of intensity VII–VIII were felt throughout the west of France.

Location

The passage du Gois, in the Bay of Bourgneuf, links Beauvoir-sur-Mer on the mainland to Barbâtre on the île de Noirmoutier.

Another reference in terms of regional seismicity is the 1972 earthquake on the island of Oléron in Loire-Atlantique and in Vendée

The earthquake of 25 January 1799 was located in the Marais Breton marshland, a wetland located on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean which marks the limit between the two former French provinces of Brittany and Poitou and extends over the two departments of Loire-Atlantique and Vendée in the French region of Pays de la Loire.[2]

The epicenter was located at sea, in the bay of Bourgneuf, between Barbâtre at the entrance to the island of Noirmoutier and Bouin on the mainland. The most significant damage occurred in Bouin, Machecoul, Bois-de-Céné, La Garnache, Beauvoir-sur-Mer and Barbâtre areas.[2]

The earthquake was felt all along the coast, as far as Vannes in the north and La Rochelle in the south,[2][3] and up to a distance of one hundred and fifty to two hundred kilometres inland. The Grand-Ouest of France was shaken from Brittany to Normandy, from Berry to Anjou and Touraine, from Limousin to Poitou, from Saintonge to Aunis and Bordelais, in Auvergne, in the Morvan and as far as Île-de-France.[2][4]

- Landscape of the Vendéen Marais Breton at Bouin.

- Church of Our Lady of Bouin (14th century):[5]

....the spire of the steeple, all in dressed stone, built with cement, is about to fall...

- Landscape of the Marais breton-vendéen near Bois-de-Céné.

- The marshes at Beauvoir-sur-Mer.

- The marshes towards Bourgneuf-en-Retz.

Characteristics

The earthquake of 25 January 1799 is one of the major events of the Grand-Ouest of France. By its magnitude and intensity of VIII, maximum for the Armorican Massif, it constitutes the most important earthquake recorded to date in this region and it is one of the six historic earthquakes to have had destructive effects in metropolitan France along with those from Basel near the French border (intensity IX–X) in 1356, Bagnères-de-Bigorre (intensity VIII–IX) in 1660, Remiremont (intensity VIII) in 1682, from the Ligurian sea off the Côte d'Azur (intensity X) in 1887 and Lambesc (intensity IX) in 1909[2][6][7] that of Arette (intensity VIII–IX) in 1967 being the first earthquake with destructive effect in mainland France to be documented by instrumental seismicity.[8]

The 6 Pluviose of the Year VII of the Republic, around 4 am, the population of the Vendée was suddenly awakened by the earthquake that would add its ruins to those of a region already hit by the War in the Vendée still nearby and by the harsh climatic conditions of the winter of 1799.[2]

In Bouin the duration of the tremor was a "half-minute" and its direction from south to north.[2]

Several recent studies have made it possible to estimate the magnitude at 6.4 and the depth at 24 km, estimates adopted by the Bureau of Geological and Mining Research.[9]

The intensity was of the order of VII–VIII at the epicenter, the centre of the tremor not being located in the heart of the marshland as initially advanced but more to the west, at sea, in the bay of Bourgneuf. In the hardest hit area, the earthquake is estimated to have reached intensity VIII due to the lower resistance of the sediments making up the marsh, which locally amplified the seismic movement.[2] Intensity decreases with increasing distance but remained significant in Nantes and Les Sables-d'Olonne (VI–VII), La Rochelle, Ile d'Oléron and Belle-Île-en-Mer (VI). It was still V–IV in Tours, Guernsey, Vannes, Châteauroux, Rennes and Limoges and weaker (III) but still felt in Paris, Bordeaux or Caen.[9]

Several aftershocks occurred in the sector of Bouin and Machecoul, on 27 and 28 January, then on 5 and 6 February.[2] The variations in the movement of the waters of the region demonstrate that the earthquake was indeed underwater and that it may have given rise to a tsunami.[10]

Probable cause

The collision between the Aquitaine and Armorican tectonic plates gave birth in the Carboniferous period to the Hercynian basement of the Armorican massif creating faults oriented north-west, south-east, which go from the Pointe du Raz to Nantes and the Landes de Lanvaux to Angers and extend south of the Loire estuary. These shear fractures are at the origin of grabens which are accentuated during the Mesozoic and the Cenozoic, and fill up with sediments that may be more than 100 m thick in the deepest ditches. They are still active in the Quaternary and their replay explains the earthquakes of the south of the Loire and more particularly those of the Vendée.[10][11]

The municipalities where the greatest damage was reported (Bouin, Machecoul) are close to these fractures, as are the localities where the earthquake was felt with force even if the damage was less ( Champtoceaux, Beauvoir-sur-Mer, Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie, Nantes, La Brière, Tiffauges, and, further on, La Flèche).[10] The epicenter was located on the continental shelf off the island of Noirmoutier, in Bourgneuf bay. The earthquake caused a large wave felt in Belle-Île-en-Mer, La Rochelle and in the Loire Valley.[10]

Damage

In some villages, Bouin and Machecoul in particular, the shock was so violent that many houses cracked or collapsed.[4][10]

In Bouin there were two types of constructions, those of the town, built on a hard limestone hillock in the middle of the marshes and constructed from stones extracted from the hill itself and those of the marsh, built on mudflats - far more fragile buildings which could not be repaired after the shocks. About 6-8% of the total number of houses were close to ruin (14 collapsed and 150 damaged). These were probably the most fragile. Lightweight constructions were not, however, the only buildings affected by the earthquake, as one testimony reports: "the spire of the steeple, all in dressed stone, built with cement, is on the verge of falling".[10][11][12]

The observations made at Machecoul are quite comparable. Here too, it was especially the fragile buildings of the marshes that seem to be the most affected. Most of the houses damaged during the civil war had only been repaired temporarily and were all the more weakened.[10][12]

Damage was also noted in La Garnache, 6 km northeast of Challans, in the Bois-de-Céné marsh area, in Barbâtre, a town which, partly destroyed by the earthquake, lost its title of municipality and was united in Noirmoutier, and Bourgneuf-en-Retz. The unique case of a house destroyed in Champtoceaux in Maine-et-Loire, a village on the left bank of the Loire about 25 kilometers upstream from Nantes was also reported.[10]

In the Marais, the towns of Noirmoutier, Beauvoir-sur-Mer and Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie strongly felt the tremors without any damage being reported however. In the neighbouring areas of the Marais, fairly detailed information on the effects of the earthquake was reported for Nantes, Saint-Lyphard en Brière,[12] Tiffauges, around the Lac de Grand-Lieu, near the Temple but also for the municipalities of the neighbouring departments like Vannes and Josselin in Morbihan, Le Mans, La Flèche, La Ferté-Bernard in Sarthe, Angers, Beaufort-en-Vallée in Maine-et-Loire, Rennes, La Guerche in Ille-et-Vilaine, La Rochelle in Charente-Maritime.[10]

Significant water movements are indicated by letters and newspaper articles: flooding, submersion of dykes, strong wave shaking boats, abnormal rises of rivers, etc., south of the Loire as near Bouin (submersion of dykes and wave), in Bourgneuf (waves and land transport), in La Rochelle (wave) as well as in the north of the Loire as in Nantes (waves), in Brière near Saint-Nazaire (water movements) or again at Belle-Île-en-Mer (dyke submersion).[10]

Some of the water movements, in particular floods and abnormal rises in rivers, are of dubious cause. They could equally be explained by a sudden thaw removing the ice dams in the rivers reported a few weeks earlier as by a tidal wave. Other observations, made just after the earthquake (strong wave shaking the boats, submersion of the dikes), are more convincing. They seem to show that the epicenter of the earthquake was at sea and not around Bouin as first thought. This wave and these submersions could be due to a tsunami.[10]

Consequences on the local economy

Salt from Noirmoutier.

Beyond the destruction of buildings and superstructures, the more or less long-term consequences of the earthquake on the local economy were reported in particular to the central administration of Loire-Inférieure by the municipal administration of Herbignac which indicates the 1st March 1799 (11 Ventose year VII) that the population of the municipalities of La Briere in St-Hyphard and Herbignac that "... usually draw clods which are used for heating the township and still supply all the surrounding townships and allow them to live for two thirds of the year" showed losses caused by the earthquake. Likewise, the municipal administration of Machecoul pointed out that if the owners succeeded in partially re-establishing the crops destroyed by the civil war, they had not yet derived any benefit from it at the date of the earthquake and that "the lowlands both in the upper and lower marshes of the municipality de Machecoul will not yet produce anything this year, these lands have been under water for more than two months, the wheat will be rotten like last year".[12]

Informing the authorities

The Commissioners of the Directory such as Sieur Mignon, Commissioner of the executive board for the canton of Bouin, informed the "Citizen Minister" of the event. The central administration of Loire-Inférieure was quickly warned of the significant damage suffered in the town of Machecoul. From the coast and up to a distance of one hundred and fifty to two hundred kilometers inland, the earthquake created such a commotion that the central administration near all the departments close to the earthquake did not fail to inform the Minister of the Interior, from Nantes, Laval, Le Mans, Tours, Poitiers, Châteauroux, Fontenay-le-Comte, Châteaubriant, etc.[2][4][12]

Press coverage

The local press, Le Publicateur de Nantes, La Feuille Nantes, Les Étrennes de Nantes, L'Ami de la liberté, La Feuille du jour, etc. recount the event over several days, relayed by the national press, Le Bien Informé, La Gazette nationale, Les Annales de la République. In this period of development of the written press, these pages are important sources of information for future seismology when the original records are lost: they indeed publish the testimonies and the communiques of the authorities, directly or with the hindsight and analysis of their own.[12]

Testimonials

The writings which relate the effects of the earthquake are marked by the proximity of the Vendée War which ravaged the region, and must be considered in this historical framework. The letters from the local administrators describe the damage most accurately and precisely. Newspapers can provide additional insight, but their information should be examined with caution.[10][12]

Other earthquakes in the region

No other example of an earthquake of such magnitude has been identified in the area The only tremors recorded are minor and were noted on the island of Noirmoutier (23 August 1747, 5 February 1833, 15 October 1945 and 22 June 2005) and Bourgneuf-en-Retz (7 April 1767). On the Atlantic coast near the marsh, however, approaching tremors were noted at Vannes (intensity VII) on 9 January 1930, in Quimper (intensity VII) on 2 January 1959 and on the island of Oléron (intensity VII), 7 September 1972.[2]

Contemporary projections

Bouin, like all the communes of the Vendée and the 146 communes of the south of Loire-Atlantique, is classified in seismicity zone 3 (moderate risk).[13]

The authors of the 2016 Geological and Mining Research Bureau study report "Impact of the 1799 earthquake on current buildings in the departments of Loire-Atlantique (44) and Vendée (85)",[9] modelled the 1799 earthquake in the contemporary setting of the two departments. They estimated damage of the order of 10,000 to 12,000 uninhabitable buildings would occur, i.e. a much larger consequence than at the time due to the urbanisation that has since taken place and in particular on poor quality land on which would reproduce, on buildings constructed before the implementation of the 2011 building regulations, the known effects on the mudflats of the Marais Breton in 1799.[9]

In 2019, Caroline Kaub proposed in her thesis to "characterise the geometry of possible plio-Quaternary and potentially active faults in this region, with a particular interest in the Machecoul fault, bordering the sedimentary basins of the Breton Marsh and the Bay of Bourgneuf and potential candidate for the Vendéen earthquake of 1799 [suggesting] that the plio-Quaternary sedimentation of the sea and land basins south of the Machecoul fault could be controlled by this fault probably inherited from the Eocene [and in providing] a bundle of clues making it possible to link the Machecoul fault to the rupture of the Vendéen earthquake of 1799".[14][15]

The Bouin earthquake is the reference earthquake[clarify] for the Blayais Nuclear Power Plant.[16]

Notes and references

- ^ The active faults involved in this earthquake of which the epicentre is localised in the Bay of Bourgneuf, are not shown on the map. See their representation in: Limasset, Jean-Claude; Limasset, Odette; Martin, Jean-Clément (1992). "Histoire et étude des séismes" [History and study of earthquakes]. Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest (in French). 99 (2): 115. doi:10.3406/abpo.1992.3421.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lambert, J.; Ministère de l'Écologie (June 2013). "Le séisme du Marais breton-vendéen du 25 janvier 1799" (PDF). sisfrance.irsn.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ Henot, Steve (4 February 2015). "Séismes : un phénomène habituel en Deux-Sèvres" [Earthquakes : a habitual problem in the Deux-Sevres area]. La Nouvelle République (in French).

- ^ a b c Quenet, Grégory (2005). Les tremblements de terre aux XVIIeme et XVIIIeme siècles: la naissance d'un risque [Earthquakes in the 17th and 18th centuries: the birth of a risk] (in French). Seyssel: Éditions Champ Vallon. ISBN 2-87673-414-1. BnF 39972228.

- ^ Église Notre-Dame de Bouin Base Mérimée: PA00110053, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ "Séisme d'Oléron (Charente-Maritime) 18 avril 2005. Sismicité antérieure et contexte sismotectonique" (in French). Commissariat à l'énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives.

- ^ Bossu, Rémy; Guilbert, Jocelyn; Feignier, Bruno (2016). Où sera le prochain séisme ? : défis de la sismologie au XXIeme siècle [Where will the next earthquake be? : Challenges of seismology in the 21st century] (in French). Les Ulis: EDP Sciences. ISBN 978-2-7598-0942-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) BnF 45107858 - ^ "Séisme d'Arette (France) du 13 août 1967" (PDF) (in French). Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ a b c d Rey, J.; Monfort-Climent, D.; Tinard, Pierre (September 2016). "Impact du séisme de 1799 sur le bâti courant des départements de Loire-Atlantique (44) et de Vendée (85)" (PDF) (in French). BGRM.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Limasset, Jean-Claude; Limasset, Odette; Martin, Jean-Clément (1992). "Histoire et étude des séismes" [History and study of earthquakes]. Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest (in French). 99 (99–2): 97–116. doi:10.3406/abpo.1992.3421.

- ^ a b Rothé, Jean-Pierre (1984). Séismes et volcans [Earthquakes and Volcanoes] (in French) (8 ed.). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-038626-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) BnF 34770475 - ^ a b c d e f g Fradet, Thibault (2016). Vulnérabilité et perception face aux tremblements de terre en France, 1650-1850 (PDF) (in French). Université Paris-Saclay. pp. 57–67–78–79–84–92. (NB: The author sometimes erroneously refers to the Marais Poitevin instead of the Marais Breton)

- ^ "Commune de Bouin. Information sur les risques naturels et technologiques" (PDF) (in French). bouin.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-30.

- ^ Kaub, Caroline (2019). "Déformation active intraplaque : étude pluridisciplinaire terre-mer du risque sismique en Vendée, à partir du séisme du Marais Breton de 1799 (M6)" (PDF). Université de Bretagne-Occidentale.

- ^ Kaub, Caroline (2018). "Étude de l'activité sismique et des failles du Marais Breton : approche pluridisciplinaire" (PDF). Réseau sismologique et géodésique français Résif-Epos..

- ^ Autorité de sûreté nucléaire (2 June 2003). "Réexamens de sûreté des centrales nucléaires VD2 1300 MWe et VD3 900 MWe. Détermination des mouvements sismiques à prendre en compte pour la sûreté des installations nucléaires, en application de la RFS 2001-01" (PDF) (in French). observ.nucleaire.free.fr.

![Church of Our Lady of Bouin (14th century):[5] ...the spire of the steeple, all in dressed stone, built with cement, is about to fall... .](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Eglise_de_Bouin_85230.jpg/120px-Eglise_de_Bouin_85230.jpg)

![The castle [fr] of Gilles de Retz at Machecoul burned during the War in the Vendée.](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Chateau_de_Machecoul_%28_de_Gilles_de_Rais_%29.jpg/180px-Chateau_de_Machecoul_%28_de_Gilles_de_Rais_%29.jpg)