Enver Pasha

İsmail Enver | |

|---|---|

Enver Bey in 1911 | |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 3 January 1914 – 13 October 1918 | |

| Prime Minister | Mehmed Talaat Pasha Said Halim Pasha |

| Preceded by | Ahmet Izzet Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmet Izzet Pasha |

| Chief of the General Staff | |

| In office 8 January 1914 – 13 October 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Mehmed Hâdî Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Izzet Pasha |

| Deputy Commander-in-Chief | |

| In office 8 January 1914 – 10 August 1918 | |

| Monarchs | Mehmed V Mehmed VI |

| Chief of Staff of the Commander-in-Chief | |

| In office 10 August 1918 – 13 October 1918 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed VI |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 November 1881 Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (present-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 4 August 1922 (aged 40) Bukharan People's Soviet Republic (present-day Tajikistan) |

| Resting place | Monument of Liberty, Istanbul, Turkey 41°04′05″N 28°58′55″E / 41.06814°N 28.982041°E |

| Political party | Union and Progress Party |

| Spouse | Emine Naciye Sultan |

| Children | Mahpeyker Hanımsultan Türkan Hanımsultan Sultanzade Ali Bey |

| Alma mater | Army War College (1903)[1] |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Ottoman Army |

| Years of service | 1903–1918 |

| Rank | Mirliva and the de facto Commander-in-Chief |

| Commands | Army of Islam Yildirim Army Group Third Army |

| Battles/wars | |

İsmail Enver (Ottoman Turkish: اسماعیل انور پاشا; Turkish: İsmail Enver Paşa; 23 November 1881[2] – 4 August 1922), better known as Enver Pasha, was an Ottoman Turkish military officer, revolutionary, and convicted war criminal[3][4] who was a part of the dictatorial triumvirate known as the "Three Pashas" (along with Talaat Pasha and Cemal Pasha) in the Ottoman Empire.

While stationed in Ottoman Macedonia, Enver joined the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization affiliated with the Young Turks movement that was agitating against Sultan Abdul Hamid II's despotic rule. He was a key leader of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, which reestablished the Constitution and parliamentary democracy in the Ottoman Empire. Along with Ahmed Niyazi, Enver was hailed as "hero of the revolution". However, a series of crises in the Empire, including the 31 March Incident, the Balkan Wars, and the power struggle with the Freedom and Accord Party, left Enver and the Unionists disillusioned with liberal Ottomanism. After the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état brought the CUP directly to power, Enver became War Minister, while Talaat assumed control over the civilian government.

As war minister and de facto Commander-in-Chief (despite his role as the de jure Deputy Commander-in-Chief, as the Sultan formally held the title), Enver was one of the most powerful figures in the Ottoman government.[5][6][7] He initiated the formation of an alliance with Germany, and was instrumental in the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I. He then led a disastrous attack on Russian forces in the Battle of Sarikamish, after which he blamed Armenians for his defeat. Along with Talaat, he was one of the principal perpetrators of the Late Ottoman Genocides[8][9][10] and thus is held responsible for the death of between 800,000 and 1,800,000[11][12][13][14] Armenians, 750,000 Assyrians and 500,000 Greeks. Following defeat in World War I, Enver, along with other leading Unionists, escaped the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Military Tribunal convicted him and other Unionists and sentenced them to death in absentia for bringing the Empire into World War I and organizing massacres against Greeks and Armenians. Enver ended up in Central Asia, where he was killed leading the Basmachi Revolt against the Bolsheviks. In 1996, his remains were reburied in Turkey. Enver was subsequently rehabilitated by Turkish president Süleyman Demirel, who praised his contributions to Turkish nationalism.

As Enver rose through the ranks of the military, he was known by increasingly esteemed titles, including Enver Efendi (انور افندی), Enver Bey (انور بك), and finally Enver Pasha. "Pasha" was the honorary title granted to Ottoman military officers upon promotion to the rank of Mirliva (major general).

Early life and career

Enver was born in Constantinople (Istanbul) on 22 November 1881.[15] Enver's father, Ahmed (c. 1860–1947), was either a bridge-keeper in Monastir (modern Bitola)[16] or an Albanian small town public prosecutor in the Balkans.[17] His mother Ayşe Dilara was a Tatar.[18] According to Şuhnaz Yilmaz, he was of Gagauz descent.[15] His uncle was Halil Pasha (later Kut). Enver had two younger brothers, Nuri and Mehmed Kamil, and two younger sisters, Hasene and Mediha. He was the brother-in-law of Lieutenant Colonel Ömer Nâzım.[19] At age six, Enver moved with his father to Monastir, where he attended primary school.[20] He studied at several military institutions. In 1902, he graduated from the Ottoman Military Academy as a Mektebli.[20]

Between 1903 and 1908, Enver was stationed in Ottoman Macedonia, where he helped suppress the Macedonian Struggle. He fought no less than 54 engagements, mostly against Bulgarian bands, developing a reputation as an expert counterinsurgent. During his service, he became convinced of the need for reforms in the Ottoman military.[21][22]

Joining the CUP

Enver, through the assistance of his uncle, Halil Kut, became the twelfth member of the nascent Ottoman Freedom Society (OFS).[23] The OFS later merged with the Paris-based Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) led by Ahmed Rıza.[23] The CUP gained access to the Third Army through Enver.[23] Upon his return to Monastir in 1906, Enver formed a CUP cell within the town and worked closely with Ottoman officer Kâzım Karabekir.[23] Enver became the main figure in the CUP Monastir branch, and he initiated Ottoman officers like Ahmet Niyazi bey and Eyüp Sabri into the CUP organisation.[24][23]

In the early twentieth century some prominent Young Turk members such as Enver developed a strong interest in the ideas of Gustave Le Bon.[25] For example, Enver saw deputies as mediocre and in reference to Le Bon he thought that as a collective mind they had the potential to become dangerous and be the same as a despotic leader.[26] As the CUP shifted away from the ideas of members who belonged to the old core of the organisation to those of the newer membership, this change assisted individuals like Enver in gaining a larger profile in the Young Turk movement.[27]

In Ohri (modern Ohrid) an armed band (çete) called the Special Muslim Organisation (SMO) composed mostly of notables was created in 1907 to protect local Muslims and fight Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) bands.[28] Enver along with Sabri recruited the SMO and turned it into the Ohri branch of the CUP with its band becoming the local CUP band.[29] CUP Internal headquarters proposed that Enver go form a CUP band in the countryside.[19] Approving the decision by the committee to assassinate his brother in law Lieutenant Colonel Ömer Nâzım, Enver under instructions from CUP headquarters traveled from Selanik (Thessaloniki) to Tikveş on 26 June 1908 to establish a band.[19] CUP headquarters conferred upon Enver the title of "CUP Inspector General of Internal Organisation and Executive Forces".[19]

Young Turk Revolution

On 3 July 1908, Niyazi, protesting the rule of Abdul Hamid II, fled with his band from Resne (modern Resen) into the mountains where he initiated the Young Turk Revolution and issued a proclamation that called for the restoration of the constitution of 1876.[31] Following his example, Enver in Tikveş, and other officers such as Sabri in Ohri, also went into the mountains and formed guerilla bands.[32][31] It is unclear whether the CUP had a fixed date for the revolution; in comments made in an interview following the event Enver stated that they planned for action in August 1908, yet events had forced them to begin the revolution at an earlier time.[33] For the revolt to get local support Enver and Niyazi played on fears of possible foreign intervention.[34] Enver led a band composed of volunteers and deserters.[35] For example, he allowed a deserter who had engaged in brigandage in areas west of the river Vardar to join his band at Tikveș.[29] Throughout the revolution, guerilla bands of both Enver and Niyazi consisted of Muslim (mostly Albanian) paramilitaries.[36]

Enver sent an ultimatum to the Inspector General on 11 July 1908 and demanded that within 48 hours Abdul Hamid II issue a decree for CUP members that had been arrested and sent to Constantinople to be freed.[35] He warned that if the ultimatum was not complied with by the Inspector General, he would refuse to accept any responsibility for future actions.[35] In Tikveș a handwritten appeal was distributed to locals calling for them to either stay neutral or join with him.[35] Enver possessed strong authority among fellow Muslims in the area where he resided and could communicate with them as he spoke both Albanian and Turkish.[37] During the revolution, Enver stayed in the homes of notables, and as a sign of respect they would kiss his hands since he had earlier saved them from an attack by an IMRO band.[38] He stated that the CUP had no support in the countryside apart from a few large landowners with CUP membership that lived in towns, yet they retained influence in their villages and were able to mobilise the population for the cause.[39] Whole settlements were enrolled into the CUP through councils of village elders convened by Enver in Turkish villages of the Tikveş region.[39] As the revolution spread by the third week and more officers deserted the army to join the cause, Enver and Niyazi got like minded officials and civilian notables to send multiple petitions to the Ottoman palace.[40] Enver wrote in his memoirs that while he still was involved in band activity in the days toward the end of the revolution he composed more detailed rules of engagement for use by paramilitary units and bands.[28]

On 23 July he proclaimed an age of liberty in front of the government mansion of Köprülü.[41] In Salonica, he spoke from the balconies of the Grand Hôtel D'Angleterre to a crowd in the city center, where he declared that absolutism was finished, and Ottomanism would prevail.[42] The square would be named Eleftherias Square, or the Square of Liberty thereafter.[42] Facing a deteriorating situation in the Balkans, on 24 July Sultan Abdul Hamid II restored the constitution of 1876.[43]

Aftermath

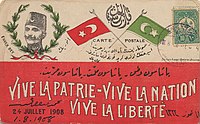

In the aftermath of the revolution, Niyazi and Enver remained in the political background due to their youth and junior military ranks with both agreeing that photographs of them would not be distributed to the general public; however, this decision was rarely honoured.[45] Instead, Niyazi and Enver as leaders of the revolution elevated their positions to near legendary status, with their images placed on postcards and distributed throughout the Ottoman state.[46][47] Toward the latter part of 1908, photographs of Niyazi and Enver had reached Constantinople and school children of the time played with masks on their faces that depicted the revolutionaries.[48] In other images produced at the same time, the sultan is presented in the centre, flanked by Niyazi and Enver to either side.[30] As the actions of both men carried the appearance of initiating the revolution, Niyazi, an Albanian, and Enver, a Turk, later received popular acclaim as "heroes of freedom" (hürriyet kahramanları) and symbolised Albanian-Turkish cooperation.[49][50]

As a tribute to his role in the Young Turk Revolution that began the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire, Niyazi is mentioned along with Enver in the March of the Deputies (Turkish: Mebusan Marşı or Meclis-i Mebusan Marşı), the anthem of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Ottoman parliament.[51][52] It was performed in 1909 upon the opening of the new parliament.[51][52] The fourth line of the anthem reads "Long live Niyazi, long live Enver" (Turkish: "Yaşasın Niyazi, yaşasın Enver").[52][53] The Ottoman newspaper Volkan, a strong supporter of the constitution published adulatory pieces about Enver and Niyazi in 1909.[54]

Following the revolution, Enver rose within the ranks of the Ottoman military and had an important role within army–committee relations.[55] By 1909 he was the military attaché at Berlin and formed personal ties with high ranking German state officials and the Kaiser.[55] It was during this time that Enver came to admire the culture of Germany and power of the German military.[55] He invited German officers to reform the Ottoman Army. In 1909 a reactionary conspiracy to organise a countercoup culminated in the 31 March Incident; the countercoup was put down.[55] Enver for a short time in April 1909 returned to Constantinople and joined the Action Army.[55] As such he took an active role in the suppression of the countercoup, which resulted in the overthrow of Abdul Hamid II, who was replaced by his brother Mehmed V, while the power of the CUP was consolidated.[55] Throughout the Young Turk era, Enver was a member of the CUP central committee from 1908 to 1918.[56]

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911, Italy launched an invasion of the Ottoman vilayet of Tripolitania (Trablus-i Garb, modern Libya), starting the Italo-Turkish War. Enver decided to join the defense of the province and left Berlin for Libya. There, he assumed the overall command after successfully mobilizing 20,000 troops.[57] Because of the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, however, Enver and other Ottoman generals in Libya were called back to Constantinople. This allowed Italy to take control of Libya. In 1912, thanks to his active role in the war, he was made lieutenant colonel.[58]

However, the loss of Libya cost the CUP in popularity, and it fell from government after rigging the 1912 elections (known as the Sopalı Seçimler, "Election of Clubs"), to be replaced by the Freedom and Accord Party (which was helped by its military arm, the Savior Officers, that denounced the CUP's actions during the 1912 elections).

Balkan Wars and 1913 coup

In October 1912, the First Balkan War broke out, and the Ottoman armies suffered severe defeats at the hands of the Balkan League. These military reversals weakened the government, and gave the committee the chance to seize power from Freedom and Accord. In a coup in January 1913, Enver and CUP leader Mehmed Talaat regained power for the committee and introduced a triumvirate that came to be called the "Three Pashas" which included Enver, Talaat, and Ahmed Cemal Pasha. Turkey then withdrew from the peace negotiations then under way in London and did not sign the Treaty of London (1913), resuming the First Balkan War. The change in government did not change the fact that the war was lost, and the Ottoman Empire gave up almost all of its Balkan territory to the Balkan League. Afterwards the Grand Vizier Mahmud Shevket Pasha was assassinated, allowing the CUP to take full control over the empire.

In June 1913, however, the Second Balkan War broke out between the Balkan Allies. Enver Bey took advantage of the situation and led an army into Eastern Thrace, recovering Adrianople (Edirne) from the Bulgarians, who had concentrated their forces against the Serbs and Greeks, with the Treaty of Constantinople (1913). Enver is therefore recognised by some Turks as the "conqueror of Edirne".

In 1914, he became Minister of War in the cabinet of Said Halim Pasha, and married HIH Princess Emine Naciye Sultan (1898–1957), the daughter of Prince Süleyman, thus entering the royal family as a damat ("bridegroom" to the ruling House of Osman).

World War I

Being able to communicate in German,[59] Enver Pasha, along with Talaat and Halil Bey were architects of the Ottoman-German Alliance, and expected a quick victory in the war that would benefit the Ottoman Empire. Without informing the cabinet, he allowed the two German warships SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau, under the command of German admiral Wilhelm Souchon, to enter the Dardanelles to escape British pursuit; the subsequent "donation" of the ships to the neutral Ottomans worked powerfully in Germany's favor, despite French and Russian diplomacy to keep the Ottoman Empire out of the war. Finally on 29 October, the point of no return was reached when Admiral Souchon, now Commander-in-Chief of the Ottoman navy, took Goeben, Breslau, and a squadron of Ottoman warships into the Black Sea and bombed the Russian ports of Odessa, Sevastopol, and Theodosia. Russia declared war on Ottoman Empire on 2 November, and Britain followed suit on 5 November. Most of the Turkish cabinet members and CUP leaders were against such a rushed entry to the war, but Enver Pasha held that it was the right course of action.

As soon as the war started, 31 October 1914, Enver ordered that all men of military age report to army recruiting offices. The offices were unable to handle the vast flood of men, and long delays occurred. This had the effect of ruining the crop harvest for that year.[60]

Battle of Sarikamish, 1914

Enver Pasha assumed command of the Ottoman forces arrayed against the Russians in the Caucasus theatre. He wanted to encircle the Russians, force them out of Ottoman territory, and take back Kars and Batumi, which had been ceded after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. Enver thought of himself as a great military leader, while the German military adviser, Liman von Sanders, thought of him as incompetent.[60] Enver ordered a complex attack on the Russians, placed himself in personal control of the Third Army, and was utterly defeated at the Battle of Sarikamish in December 1914 – January 1915. His strategy seemed feasible on paper, but he had ignored external conditions, such as the terrain and the weather. Enver's army (118,000 men) was defeated by the Russian force (80,000 men), and in the subsequent retreat, tens of thousands of Turkish soldiers died. This was the single worst Ottoman defeat of World War I. On his return to Constantinople, Enver Pasha blamed his failure on his Armenian soldiers, although in January 1915, an Armenian named Hovannes had saved his life during a battle by carrying Enver through battle lines on his back.[61] Nonetheless, Enver Pasha later initiated the deportations and sporadic massacres of Western Armenians, culminating in the Armenian genocide.[62][63][64][65]

Commanding the forces of the capital, 1915–1918

After his defeat at Sarıkamısh, Enver returned to Istanbul (Constantinople) and took command of the Turkish forces around the capital. He was confident that the capital was safe from any Allied attacks.[66] The British and French were planning on forcing the approaches to Constantinople in the hope of knocking the Ottomans out of the war. A large Allied fleet assembled and staged an attack on the Dardanelles on 18 March 1915. The attack (the forerunner to the failed Gallipoli campaign) was a disaster, resulting in the loss of several ships. As a result, Enver turned over command to Liman von Sanders, who led the successful defence of Gallipoli. Enver then left to attend to pressing concerns on the Caucasus Front. Later, after many towns on the peninsula had been destroyed and women and children killed by the Allied bombardment, Enver proposed setting up a concentration camp for the remaining French and British citizens in the empire. Henry Morgenthau, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, convinced Enver not to go through with this plan.[67]

Yildirim

Enver's plan for Falkenhayn's Yildirim Army Group was to retake Baghdad, recently taken by Maude.[citation needed] This was nearly impossible for logistical reasons. Turkish troops were deserting freely, and when Enver visited Beirut in June 1917, soldiers were forbidden to be stationed along his route for fear that he would be assassinated. Lack of rolling stock meant that troops were often detrained at Damascus and marched south.[68]

Army of Islam

During 1917, due to the Russian Revolution and subsequent Civil War, the Russian army in the Caucasus fell apart and dissolved. At the same time, the CUP managed to win the friendship of the Bolsheviks with the signing of the Ottoman-Russian friendship treaty (1 January 1918). Enver looked for victory when Russia withdrew from the Caucasus region. When Enver discussed his plans for taking over southern Russia, he ordered the creation of a new military force called the Army of Islam which would have no German officers. Enver's Army of Islam avoided Georgia and marched through Azerbaijan. The Third Army under Vehib Pasha was also moving forward to pre-war borders and towards the First Republic of Armenia, which formed the frontline in the Caucasus. General Tovmas Nazarbekian was the commander on the Caucasus front, and Andranik Ozanian took the command of Armenia within the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman advance was halted at the Battle of Sardarabad.[citation needed]

The Army of Islam, under the control of Nuri Pasha, moved forward and attacked Australian, New Zealand, British, and Canadian troops led by General Lionel Charles Dunsterville at Baku. General Dunsterville ordered the evacuation of the city on 14 September, after six weeks of occupation, and withdrew to Iran.[69] As the Army of Islam and their Azerbaijani allies entered the city on September 15 following the Battle of Baku, up to 30,000 Armenian civilians were massacred. [citation needed]

However, after the Armistice of Mudros between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire on 30 October, Ottoman troops were obliged to withdraw and replaced by the Triple Entente. These conquests in the Caucasus counted for very little in the war as a whole but they did however ensure that Baku remained within the boundaries of Azerbaijan while a part of the Soviet Union and later as an independent nation.

Armistice and exile

Faced with defeat, the Sultan dismissed Enver from his post as War Minister on 4 October 1918, while the rest of Talaat Pasha's government resigned on 14 October 1918. On 30 October 1918, the Ottoman Empire capitulated by signing the Armistice of Mudros. Two days later, the "Three Pashas" all fled into exile. On 1 January 1919, the new government expelled Enver Pasha from the army. He was tried in absentia in the Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919–20 for crimes of "plunging the country into war without a legitimate reason, forced deportation of Armenians and leaving the country without permission" and condemned to death.[70]

Enver first attempted to link up with Halil and Nuri to reopen the Caucasus campaign, but his boat ran aground and hearing the army was demobilizing he gave up and went to Berlin like the other Unionists émigrés did. He settled in Babelsberg, and in April 1919 after meeting with Karl Radek with Talaat, he took on the role of a secret envoy for his friend General Hans von Seeckt who wished for a German-Soviet alliance.[71] In August 1920, Enver sent Seeckt a letter in which he offered on behalf of the Soviet Union the partition of Poland in return for German arms deliveries to Soviet Russia.[71] Besides working for General von Seeckt, Enver envisioned cooperation between the new Soviet Russian government against the British, and went to Moscow.

Accompanying Mehmed Ali Sâmi, Enver's new pseudonym, was his Unionist comrade Bahaeddin Şakir. Sâmi would be a doctor representing the Turkish Red Crescent in Russia. On 10 October 1919, their plane flight took off from the German border and stopped in Königsberg and then Šiauliai but crashed in the outskirts of Kaunas, Lithuania. Stranded in a country teeming with Allied soldiers, they weren't recognized by journalists or occupation forces until they were about to escape. They were eventually arrested for two months, but Enver and Şakir managed to escape from the Lithuanian prison back to Berlin. Enver and Şakir tried again to enter Russia by air but their plane broke down and crashed not even beyond the German border. After tending to their wounds in a near by village, they returned to Berlin. Enver's insistence to arrive to Moscow by plane costed them another plane crash in flight trials. Eventually Cemal joined the duo, and using a plane that successfully passed flight tests they set off once again for Moscow. But hearing strange noises from the engine, Enver asked the pilot to turn back. After small repairs to the plane Enver attempted a fifth flight to Moscow, where the plane disintegrated one hour into the flight. While Enver was determined to make a grand entrance from the sky, Şakir and Cemal gave up and instead joined a Russian prisoner of war convoy heading back to their homeland. Enver's new alias was now Herr Altman, "a German Jewish Communist of no importance". In his sixth attempt, a one-seat plane carrying Enver and a pilot malfunctioned in mid-air and landed in British-occupied Danzig. Enver begged the pilot to repair the plane lest he would be captured by the British. Taking off once again, they only made it as far as Königsburg. The plane once again repaired, they made it to Bolshevik occupied Estonia to refill on gas, but the Bolsheviks arrested Enver, mistaking him for a fugitive Baltic German count that fled to Germany, and imprison him in the city of Reval. Enver's case for his identity was not helped when an Estonian peasant identified him as the abusive count. Enver took up painting in prison, at one point painting a portrait of the warden and his family. With the Estonian-German peace treaty, Enver was repatriated to Germany as the German count.[72][73]

Enver finally made it to Moscow in August 1920 (he came by land in the end). There he was well-received, and established contacts with representatives from Central Asia and other exiled CUP members as the director of the Soviet Government's Asiatic Department.[74] He also met with Bolshevik leaders, including Georgy Chicherin, Radek, Grigory Zinoviev and Vladimir Lenin. He tried to support the Turkish national movement and corresponded with Mustafa Kemal, giving him the guarantee that he did not intend to intervene in the movement in Anatolia. Between 1 and 8 September 1920, he was in Baku for the Congress of the Peoples of the East, representing Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. His appearance was a personal triumph, but the congress failed in its aim to create a mass pro-Bolshevik movement among Muslims. Victor Serge, a witness, recorded that:

At Baku, Enver Pasha put in a sensational appearance. A whole hall full of Orientals broke into shouts, with scimitars and yataghans brandished aloft: 'Death to imperialism" All the same, genuine understanding with the Islamic world...was still difficult.[75]

Relations with Mustafa Kemal

Much has been written about the poor relations between Enver and Mustafa Kemal, two men who played pivotal roles in the Turkish history of the 20th century. Both hailed from the Balkans, and the two served together in North Africa during the wars preceding World War I, Enver being Mustafa Kemal's senior. Enver disliked Mustafa Kemal for his circumspect attitude toward the political agenda pursued by his Committee of Union and Progress, and regarded him as a serious rival.[76] Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk) considered Enver to be a dangerous figure who might lead the country to ruin;[77] he criticized Enver and his colleagues for their policies and their involvement of the Ottoman Empire in World War I.[78][79] In the years of upheaval that followed the Armistice of October 1918, when Mustafa Kemal led the Turkish resistance to occupying and invading forces, Enver sought to return from exile, but his attempts to do so and join the military effort were blocked by the Ankara government under Mustafa Kemal.

Last years

On 30 July 1921, with the Turkish War of Independence in full swing, Enver decided to return to Anatolia. He went to Batum to be close to the new border. However, Mustafa Kemal did not want him among the Turkish revolutionaries. Mustafa Kemal had stopped all friendly ties with Enver Pasha and the CUP as early as 1912,[77] and he explicitly rejected the pan-Turkic ideas and what Mustafa Kemal perceived as Enver Pasha's utopian goals.[76] Enver Pasha changed his plans and traveled to Moscow where he managed to win the trust of the Soviet authorities. In November 1921 he was sent by Lenin to Bukhara in the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic to help suppress the Basmachi Revolt against the local pro-Moscow Bolshevik regime. Instead, however, he made secret contacts with some of the rebellion's leaders and, along with a small number of followers, defected to the Basmachi side. His aim was to unite the numerous Basmachi groups under his own command and mount a co-ordinated offensive against the Bolsheviks in order to realise his pan-Turkic dreams. After a number of successful military operations he managed to establish himself as the rebels' supreme commander, and turned their disorganized forces into a small but well-drilled army. His command structure was built along German lines and his staff included a number of experienced Turkish officers.[80]

According to David Fromkin:

However Enver's personal weaknesses reasserted themselves. He was a vain, strutting man who loved uniforms, medals and titles. For use in stamping official documents, he ordered a golden seal that described him as 'Commander-in-Chief of all the Armies of Islam, Son-in-Law of the Caliph and Representative of the Prophet.' Soon he was calling himself Emir of Turkestan, a practice not conducive to good relations with the Emir whose cause he served. At some point in the first half of 1922, the Emir of Bukhara broke off relations with him, depriving him of troops and much-needed financial support. The Emir of Afghanistan also failed to march to his aid.[81]

On 4 August 1922, as he allowed his troops to celebrate the Kurban Bayramı (Eid al-Adha) holiday while retaining a guard of 30 men at his headquarters near the village of Ab-i-Derya near Dushanbe, the Red Army Bashkir cavalry brigade under the command of ethnic Armenian, Yakov Melkumov (Hakob Melkumian), launched a surprise attack. According to some sources, Enver and some 25 of his men mounted their horses and charged the approaching troops, when Enver was killed by machine-gun fire.[82] In his memoirs, Enver Pasha's aide Yaver Suphi Bey stated that Enver Pasha died of a bullet wound right above his heart during a cavalry charge.[83] Alternatively, according to Melkumov's memoirs, Enver managed to escape on horseback and hid for four days in the village of Chaghan. His hideout was located after a Red Army officer infiltrated the village in disguise. Melkumov's troops ambushed Enver at Chaghan, and in the ensuing combat he was killed by machine gun fire.[84] Some sources write that Melkumov personally killed Enver Pasha with his sabre, although Melkumov does not claim this in his memoirs.[85][86]

Fromkin writes:

There are several accounts of how Enver died. According to the most persuasive of them, when the Russians attacked he gripped his pocket Koran and, as always, charged straight ahead. Later his decapitated body was found on the field of battle. His Koran was taken from his lifeless fingers and was filed in the archives of the Soviet secret police.[87]

Enver's body was buried near Ab-i-Derya in Tajikistan.[88] In 1996, his remains were brought to Turkey and reburied at Abide-i Hürriyet (Monument of Liberty) cemetery in Şişli, Istanbul. He was re-buried on the 4 August, the anniversary of his death in 1922.[89][90] Enver Pasha's image remains controversial in Turkey, since Enver and Atatürk had a personal rivalry at the end of the Ottoman Empire and his memory was cultivated by the Kemalists.[90] But upon his body's arrival in Turkey, he was rehabilitated by the Turkish President Süleyman Demirel who held a speech acknowledging his contributions to Turkish nationalism.[90] Following renewed hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno Karabakh region in 2020, Enver Pasha's role during World War I was praised by Turkish President Erdoğan during an Azeri victory parade in Baku.[91] In 2023, Azerbaijani officials issued a map of the formerly Armenian Stepanakert, renaming one of the streets after Pasha.[92]

Family

After Enver's death, three of his four siblings, Nuri (1889–1949), Mehmed Kamil (1900–62), and Hasene Hanım, adopted the surname "Killigil" after the 1934 Surname Law required all Turkish citizens to adopt a surname.

Enver's sister Hasene Hanım married Nazım Bey. Nazım Bey, an aid-de-camp of Abdul Hamid II, survived an assassination attempt by Talaat during the 1908 Young Turk Revolution of which his brother-in-law Enver was a leader.[93] With Nazım, Hasene gave birth to Faruk Kenç (1910–2000), who would become a famous Turkish film director and producer.

Enver's other sister, Mediha Hanım (later Mediha Orbay; 1895–1983), married Kâzım Orbay, a prominent Turkish general and politician. On 16 October 1945, their son Haşmet Orbay, Enver's nephew, shot and killed a physician named Neşet Naci Arzan, an event known as the "Ankara murder". At the urging of the Governor of Ankara, Nevzat Tandoğan, Haşmet Orbay's friend Reşit Mercan initially took the blame. After a second trial revealed Haşmet Orbay as the perpetrator, however, he was convicted. The murder became a political scandal in Turkey after the suicide of Tandoğan, the suspicious death of the case's public prosecutor Fahrettin Karaoğlan, and the resignation of Kâzım Orbay from his position as Chief of the General Staff of Turkey after his son's conviction.

Djevdet Bey who was the Vali of Van in 1915, was also a brother-in-law of his.[94]

Marriage

Around 1908, Enver Pasha became the subject of gossip about an alleged romance between him and Princess Iffet of Egypt. When this story reached Istanbul, the grand vizier, Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha decided to exploit Enver's marital eligibility by arranging a rapprochement between the Committee for Union and Progress and the imperial family.[95] After a careful search, the grand vizier chose the twelve-year-old Naciye Sultan, a granddaughter of Sultan Abdulmejid I, as Enver's future bride. Both the grand vizier and Enver's mother then notified him of this decision. Enver had never seen Naciye, and he did not trust his mother's letters, since he suspected her of being enamored with the idea of having a princess as her daughter-in-law.[95]

Therefore, he asked a reliable friend, Ahmed Rıza Bey, who was a member of the Turkish Parliament to investigate. When the latter reported favorably on the prospective bride's education and beauty, as well as on the prospective dowry, Enver took a practical view of this marriage and accepted the arrangement.[96] Naciye had been previously engaged to Şehzade Abdurrahim Hayri.[97] However, Sultan Mehmed V broke off the engagement,[98] and in April 1909,[99] when Naciye was just twelve years old, engaged her to Enver, fifteen years older than her. Following the old Ottoman pattern of life and tradition, the engagement ceremony was celebrated in Enver's absence as he remained in Berlin.[100]

The marriage took place on 15 May 1911 in the Dolmabahçe Palace, and was performed by Şeyhülislam Musa Kazım Efendi. Head clerk of the sultan Halid Ziya Bey served as Naciye's deputy, and her witnesses were director of the imperial kitchen Galib Bey, and the personal physician of the sultan Hacı Ahmed Bey. Minister of war Mahmud Şevket Pasha served as Enver's deputy, and his witnesses were aide-de-camp of the sultan Binbaşı Re'fet Bey and chamberlain of the imperial gates Ahsan Bey.[101] The wedding took place about three years later on 5 March 1914[102] in the Nişantaşı Palace.[103][104] The couple were given one of the palaces of Kuruçeşme. The marriage was very happy.[105]

On 17 May 1917, Naciye gave birth to the couple's eldest child, a daughter, Mahpeyker Hanımsultan. She was followed by a second daughter, Türkan Hanımsultan, born on 4 July 1919. Both of them were born in Istanbul.[106] During Enver's stay in Berlin, Naciye and her daughters Mahpeyker and Türkan joined him. When Enver left for Russian SSR his family remained there.[107] His son, Sultanzade Ali Bey was born in Berlin on 29 September 1921, after Enver's departure and he never saw him.[107][106] Naciye was widowed at Enver's death on 4 August 1922.[106]

After his death, Naciye remarried his brother Mehmed Kamil Killigil (1900–1962) in 1923, and had one other daughter, Rana Hanımsultan.[106]

Issue

By his wife, Enver had two daughters and a son:[106]

- Mahpeyker Hanımsultan (17 May 1917 – 3 April 2000). Married once, had a son.

- Türkan Hanımsultan (4 July 1919 – 25 December 1989). Married once, had a son.

- Sultanzade Ali Bey (29 September 1921 – 2 December 1971). Married twice, had a daughter.

In arts and culture

Enver Pasha plays an important role in The Golden House of Samarkand, a comic book by Hugo Pratt, from the Italian series Corto Maltese.

Works

- Enver authored a book in German, Enver Pascha «um Tripolis», which is his diaries during the war in Libya (1911–12).[108]

See also

References

- ^ Komutanlığı, Harp Akademileri (1968), Harp Akademilerinin 120 Yılı (in Turkish), İstanbul, p. 46

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ci̇vgi̇n, Senem (28 December 2023). "Enver Paşa ve Askeri Alandaki Reform Faaliyetleri (1914-1918)". Hazine-i Evrak Arşiv ve Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi (in Turkish). 5 (5): 129–176. doi:10.59054/hed.1386081. ISSN 2687-6515.

- ^ Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina, eds. (2005). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Abingdon, Oxon, Oxford: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0203004930.

- ^ Andreopoulos, George J., ed. (1997). Genocide : conceptual and historical dimensions (1. paperback print. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216164.

- ^ Bourne, J. M. (2001). Who's who in World War One. London: Routledge. p. 282. ISBN 0-415-14179-6. OCLC 46785141.

- ^ Maksudyan, Nazan (25 April 2019). Ottoman children and youth during World War I (First ed.). Syracuse, New York. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8156-5473-5. OCLC 1088605265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ New york times current history volume 9. 2012. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-236-26433-6. OCLC 935658756.

- ^ Henham, Ralph; Behrens, Paul, eds. (2009). The Criminal Law of Genocide: International, Comparative and Contextual Aspects. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-40949591-8.

The guilty main architects of the genocide Talaat Pasaha [...] and Enver Pasha...

- ^ Freedman, Jeri (2009). The Armenian Genocide (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. ISBN 978-1-40421825-3.

Enver Pasha, Mehmet Talat, and Ahmed Djemal were the three men who headed the CUP. They ran the Ottoman administration during World War I and planned the Armenian genocide.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2006). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (Repr. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41535385-4.

The new ruling triumvirate – Minister of Internal Affairs Talat Pasha; Minister of War Enver Pasha; and Minister of Navy Jemal Pasha – quickly established a de facto dictatorship. Under the rubric of the so-called Special Organization of the CUP, they directed, this trio would plan and oversee the Armenian genocide...

- ^ Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of violence : Ottoman past, Turkish present and collective violence against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

- ^ Auron, Yair (2000). The banality of indifference: Zionism & the Armenian genocide. Transaction. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7658-0881-3.

- ^ Forsythe, David P. (11 August 2009). Encyclopedia of human rights (Google Books). Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- ^ Chalk, Frank Robert; Jonassohn, Kurt (10 September 1990). The history and sociology of genocide: analyses and case studies. Institut montréalais des études sur le génocide. Yale University Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- ^ a b Yilmaz, Şuhnaz (1999). "An Ottoman Warrior Abroad: Enver Paşa as an Expatriate". Middle Eastern Studies. 35 (4): 42. doi:10.1080/00263209908701286. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4284039.

- ^ Kaylan, Muammer (2005), The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey, Prometheus Books, p. 75.

- ^ Akmese, Handan Nezir (2005), The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to WWI, IB Tauris, p. 44.

- ^ J. Zürcher, Erik (2014). The young turk legacy and nation building (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780857718075.

- ^ a b c d Hanioğlu 2001, p. 266.

- ^ a b Swanson, Glen W. (1980). "Enver Pasha: The Formative Years". Middle Eastern Studies. 16 (3): 193–199. doi:10.1080/00263208008700445. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4282792.

- ^ Swanson, Glen W. (1980).pp.196–197

- ^ Zürcher, Erik Jan (2014b). "Macedonians in Anatolia: The Importance of the Macedonian Roots of the Unionists for their Policies in Anatolia after 1914". Middle Eastern Studies. 50 (6): 963. doi:10.1080/00263206.2014.933422. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 24585700. S2CID 144491725.

- ^ a b c d e Zürcher 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Kansu 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 308, 311.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 311.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 291.

- ^ a b Hanioğlu 2001, p. 225.

- ^ a b Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 226.

- ^ a b Özen, Saadet (2017). "The Heroes of Hürriyet: The images in Struggle". In Lévy-Aksu, Noémi; Georgeon, François (eds.). The Young Turk Revolution and the Ottoman Empire: The Aftermath of 1918. I.B.Tauris. p. 31. ISBN 9781786720214.

- ^ a b Başkan, Birol (2014). From Religious Empires to Secular States: State Secularization in Turkey, Iran, and Russia. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781317802044.

- ^ Hale 2013, p. 35.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 262.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Hanioğlu 2001, p. 268.

- ^ Gingeras, Ryan (2014). Heroin, Organized Crime, and the Making of Modern Turkey. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780198716020.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, pp. 228, 452. "Enver Bey's mother was from a mixed Albanian-Turkish family, and he could communicate in Albanian."

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 228.

- ^ a b Zürcher, Erik Jan (2014). The Young Turk Legacy and Nation Building: From the Ottoman Empire to Atatürk's Turkey. I.B.Tauris. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780857718075.

- ^ Gingeras 2016, p. 33.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act. New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8050-8665-2.

- ^ a b Tzimos, Kyas (28 February 2018). "Έφτασε η ώρα της Πλατείας Ελευθερίας". Parallaxi.

- ^ Hanioğlu 2001, p. 275.

- ^ Bilici 2012, para. 26.

- ^ Hale, William (2013). Turkish Politics and the Military. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9781136101403.

- ^ Gingeras, Ryan (2016). Fall of the Sultanate: The Great War and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1908–1922. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780191663581.

- ^ Bilici 2012, para. 25.

- ^ Özen 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 150, 169. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ^ Zürcher, Erik Jan (1984). The Unionist Factor: The Role of the Committee of Union and Progress in the Turkish National Movement 1905–1926. Brill. p. 44. ISBN 9789004072626.

- ^ a b Güçlü, Yücel (2018). The Armenian Events Of Adana In 1909: Cemal Pasa And Beyond. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 121. ISBN 9780761869948.

- ^ a b c Böke, Pelin; Tınç, Lütfü (2008). Son Osmanlı Meclisi'nin son günleri [The last days of the last Ottoman Assembly]. Doğan Kitap. p. 22. ISBN 9789759918095.

- ^ Bilici, Faruk (2012). "Le révolutionnaire qui alluma la mèche: Ahmed Niyazi Bey de Resne [Niyazi Bey from Resne: The Revolutionary who lit the Fuse]". Cahiers balkaniques. 40. para. 27.

- ^ Vahide, Şükran (2005). Islam in Modern Turkey: An Intellectual Biography of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi. State University of New York Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780791482971.

- ^ a b c d e f Yılmaz, Șuhnaz (2016). "Revisiting Networks and Narratives: Enver Pasha's Pan-Islamic and Pan-Turkic Quest". In Moreau, Odile; Schaar, Stuart (eds.). Subversives and Mavericks in the Muslim Mediterranean: A Subaltern History. University of Texas Press. p. 144. ISBN 9781477310939.

- ^ Hanioğlu, M. Șükrü (2001). Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902–1908. Oxford University Press. p. 216. ISBN 9780199771110.

- ^ Hakyemezoğlu, Serdar, Buhara Cumhuriyeti ve Enver Paşa (in Turkish), Ezberbozanbilgiler, archived from the original on 1 October 2011, retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Enver Paşa Makalesi (in Turkish), Osmanlı Araştırmaları Sitesi, archived from the original on 1 April 2017, retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha, Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of a Genocide. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7.

- ^ a b Fromkin, David (2001). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: H. Holt. pp. 119. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ^ Derogy, Jacques. Resistance and Revenge, p. 12 Published 1986, Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-338-6.

- ^ Palmer-Fernandez, Gabriel. Encyclopedia of Religion and War, p. 139. Published 2003, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-94246-2

- ^ Tucker, Spencer. "World War I", p. 394. Published 2005, ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-420-2

- ^ Balakian, Peter. The Burning Tigris, p. 184. Published 2003, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019840-0.

- ^ Akcam, Taner. A Shameful Act, p. 143. Published 2006, Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-7932-7.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 166–68.

- ^ Woodward 1998, pp. 160–1.

- ^ Homa Katouzian, State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis, (I.B. Tauris, 2006), 141.

- ^ Refuting Genocide, U Mich, archived from the original on 4 April 2002.

- ^ a b Wheeler-Bennett, John (1967), The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, p. 126.

- ^ Hanioğlu, Şükrü. "Enver Paşa". İslâm Ansiklopedisi.

- ^ "147 ) UÇTU UÇTU, ENVER PAŞA UÇTU !." Tarihten Anektotlar. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Moorehead 1997, p. 300.

- ^ Serge, Victor (1984). emoirs of a Revolutionary. New York: Writer and Readers Publishing Inc. p. 109. ISBN 0-86316-070-0.

- ^ a b Kaylan, Muammer (8 April 2005). The Kemalists: Islamic Revival and the Fate of Secular Turkey. Prometheus Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-61592-897-2.

- ^ a b Zürcher, Erik Jan (1 January 1984). The Unionist Factor: The Rôle [sic] of the Committee of Union and Progress in the Turkish National Movement, 1905–1926. Brill. p. 59. ISBN 90-04-07262-4.

- ^ Harris, George Sellers; Criss, Bilge (2009). Studies in Atatürk's Turkey: The American Dimension. Brill. p. 85. ISBN 978-90-04-17434-4.

- ^ Rubin, Barry M; Kirişci, Kemal (1 January 2001). Turkey in World Politics: An Emerging Multiregional Power. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-55587-954-9.

- ^ Hopkirk, Peter (1986), Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin's Dream of an Empire in Asia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 160, ISBN 0192851667.

- ^ Fromkin 1989, p. 487

- ^ Kandemir, Feridun (1955), Enver Paşa'nın Son Gũnleri (in Turkish), Gũven Yayınevi, pp. 65–69.

- ^ Suphi Bey, Yaver (2007), Enver Paşa'nın Son Günleri (in Turkish), Çatı Kitapları, p. 239, ISBN 978-975-8845-28-6.

- ^ Melkumov, Ya. A. (1960), Туркестанцы [Memoirs] (in Russian), Moscow, pp. 124–127

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ "Civil War in Central Asia", Ratnik

- ^ Гайк Айрапетян. "Акоп Мелькумов". HayAdat.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Fromkin 1989, p. 488

- ^ "Lost Opportunity, Potential Disaster". Wall Street Journal. 7 November 1996. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ "Turk Enver Pasha headed for reburial". UPI. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Jung, Dietrich; Piccoli, Wolfango (October 2001). Turkey at the Crossroads: Ottoman Legacies and a Greater Middle East. Zed Books. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-85649-867-8.

- ^ Mirror-Spectator, The Armenian (11 December 2020). "At Baku Victory Parade, Aliyev Calls Yerevan, Zangezur, Sevan Historical Azerbaijani Lands, Erdogan Praises Enver Pasha". The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Vincent, Faustine (4 October 2023). "Azerbaijan reissues Nagorno-Karabakh map with street named after Turkish leader of 1915 Armenian genocide". Le Monde.fr. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ Kedourie, Sylvia (13 September 2013). Seventy-five Years of the Turkish Republic. Taylor & Francis. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-135-26705-6.

- ^ Yuhanon, B. Beth (30 April 2018). "The Methods of Killing in the Assyrian Genocide". Sayfo 1915. Gorgias Press. p. 183. doi:10.31826/9781463239961-013. ISBN 9781463239961. S2CID 198820452.

- ^ a b Rorlich, Azade-Ayse (1972). Enver Pasha and the Bolshevik Revolution. University of Wisconsin—Madison. pp. Pages=9–10.

- ^ Rorlich 1972, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Suad, Adem (6 April 2015). 100 Meşhur Aşk. Az Kitap. ISBN 978-6-054-81261-5.

- ^ Altındal, Meral (1993). Osmanlı'da harem. Altın Kitaplar Yayınevi. p. 138.

- ^ Akmeşe, Handan Nezir (12 November 2005). The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to WWI. I.B.Tauris. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-850-43797-0.

- ^ Rorlich 1972, p. 11.

- ^ Milanlıoğlu, Neval (2011). Emine Naciye Sultan'ın Hayatı (1896–1957) (in Turkish). Marmara University Institute of Social Sciences. pp. Pages=30–31.

- ^ Milanlıoğlu 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Fortna, Benjamin C. (2014). The Circassian: A Life of Eşref Bey, Late Ottoman Insurgent and Special Agent. Oxford University Press. p. 293 n. 16. ISBN 978-0-190-49244-1.

- ^ Tarih ve toplum: aylık ansiklopedik dergi, Volume 26. İletişim Yayınları/Perka A. Ş. 1934. p. 171.

- ^ Bey, Yaver Suphi (16 November 2011). Enven Paşa'nın Son Günleri. artcivic. ISBN 978-6-054-33739-2.

- ^ a b c d e ADRA, Jamil (2005). Genealogy of the Imperial Ottoman Family 2005. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Rorlich 1972, p. 79.

- ^ "Un ouvrage d'Enver Pacha". Servet-i-Funoun Partie Française (1400): 2. 4 July 1917.

Sources

- Fromkin, David (1989), A Peace to End All Peace, Avon Books

- Kansu, Aykut (1997). The Revolution of 1908 in Turkey. Brill. ISBN 9789004107915.

- Moorehead, Alan (1997), Gallipoli, Wordsworth Editions, p. 79, ISBN 1-85326-675-2.

- Woodward, David R (1998), Field Marshal Sir William Robertson, Westport, CT & London: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-95422-6.

Further reading

- Haley, Charles D. (January 1994). "The Desperate Ottoman: Enver Paşa and the German Empire – I". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 1–51. doi:10.1080/00263209408700981. JSTOR 4283613.

External links

- Enver's biography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). 1922. p. 5.

- Enver's declaration at the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East 1920

- Interview with Enver Pasha by Henry Morgenthau – American Ambassador to Constantinople (Istanbul) 1915

- Biography of Enver Pasha at Turkey in the First World War website

- Personal belongings of Enver Pasha

- Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922) Archived 5 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Enver Pasha in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW