Wikipedystka:Orlica/brudnopis

| Malurus melanocephalus | |

| Latham, 1801 | |

| |

| Systematyka | |

| Domena | |

|---|---|

| Królestwo | |

| Typ | |

| Podtyp | |

| Gromada | |

| Podgromada | |

| Nadrząd | |

| Rząd | |

| Podrząd | |

| Rodzina | |

| Gatunek |

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta |

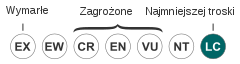

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ) | |

| |

| Zasięg występowania | |

| |

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta (Malurus melanocephalus) - gatunek ptaka z rodziny chwostek. Endemit Australii zamieszkuje brzegi rzek i tereny nadbrzeżne na północnym i wschodnim wybrzeżu Kimberley, w północnej części Hunter w Nowej Południowej Walii. Jak inne chwostki, u tego gatunku występuje wyraźni dymorfizm płciowy. Podczas okresu godowego samce są czarne, z jaskrawo czerwonym grzbietem i brązowymi skrzydłami. Samice są brązowe, z jasnym brzuchem. Młode i samce poza okresem godowym są ubarwione jak samice (niektóre samce podczas rozrodu nie zmieniaja upierzenia). Wyróżniono dwa podgatunki - melanocephalus ze wschodniej Australii o dłuższym ogonie i pomarańczowym grzbiecie i krótkoogonowy cruentatus z północnej Australii o czerwonym grzbiecie.

Chwostki czerwonogrzbiete jedzą głównie owady, swoją dietę uzupełniają małymi owocami i nasionami. Najchętniej żyją na wrzosowiskach i sawannach, zwłaszcza porośniętych niskimi krzewami i wysoką trawą. Zazwyczaj żyją w parach lub niewielkich grupach na stałym terytorium, ale na obszarach, gdzie występują częste pożary, przenoszą się z miejsca na miejsce. Grupa składa się z monogamicznej pary i jednego lub więcej ptaków, które pomagają karmić młode. Pomocnicy to zazwyczaj młode z poprzedniego lęgu, które nie są jeszcze zdolne do samodzielnego rozmnażania się.

Taksonomia

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta została po raz pierwszy schwytana w pobliżu Port Stephens w Nowej Południowej Walii. Gatunek opisał w 1801 ornitolog John Latham, nadał mu nazwę Muscicapa melanocephala. Greckie Melano oznacza "czarny", kephalos to "głowa"[1]. Osobnik opisany przez Lathama był na wpół opierzonym młodym samcem. Dorosły osobnik został opisany jako Sylvia dorsalis, a dwaj naukowcy Nicholas Aylward Vigors i Thomas Horsfield opisala ptak po raz trzeci, tym razem pod nazwą Malurus brownii, na cześć ornitologa Roberta Browna. W 1840 John Gould opisał ptaka o nazwie Malurus cruentatus, na podstawie okazu schwytanego podczas trzeciej podróży HMS Beagle. Gould odkrył także, że poprzednie trzy opisy dotyczyły jednego gatunku - Malurus melanocephalus. Utrzymywał jednak, że ptak opisany przez niego jest osobnym gatunkiem. Wkrótce potem opisano kolejnego osobnika z centralnego Queensland jako Malurus pyrrhonotus[2].

Like other fairywrens, the Red-backed Fairywren is unrelated to the true wren (family Troglodytidae). It was previously classified as a member of the old world flycatcher family Muscicapidae[3][4] and later as a member of the warbler family Sylviidae[5] before being placed in the newly recognised fairywren family Maluridae in 1975.[6] More recently, DNA analysis has shown that the Maluridae family is related to the Meliphagidae (honeyeaters), and the Pardalotidae (pardalotes, scrubwrens, thornbills, gerygones and allies) in the large superfamily Meliphagoidea.[7][8]

Within the Maluridae, it is one of 12 species in its genus, Malurus. It is most closely related to the Australian White-winged Fairywren, with which it makes up a phylogenetic clade, with the White-shouldered Fairywren of New Guinea as the next closest relative.[9] Termed the bicoloured wrens by ornithologist Richard Schodde, these three species are notable for their lack of head patterns and ear tufts, and one-coloured black or blue plumage with contrasting shoulder or wing colour; they replace each other geographically across northern Australia and New Guinea.[10]

Podgatunki

George Mack, ornitholog z National Museum of Victoria, pierwszy opisał przedstawicieli melanocephalus, cruentatus i pyrrhonotus jako jeden gatunek,[11] although Richard Schodde reclassified pyrrhonotus as a hybrid from a broad hybrid zone in North Queensland; this area is bounded by the Burdekin, Endeavour and Norman Rivers. Breeding males of intermediate plumage, larger and scarlet-backed, or smaller and orange-backed, as well as forms that resemble one of the two parent subspecies, are all encountered within it.[12] A molecular study published in 2008 focussing on the Cape York population found it was genetically closer to the eastern forest subspecies than to the Top End form. These birds became segregated around 0.27 million years ago, with some gene flow still with eastern birds.[13]

Two subspecies are recognised:

- M. m. melanocephalus, the nominate subspecies, has an orange back and longer tail and is found from northern coastal New South Wales through to North Queensland. This form has been previously called the Orange-backed Fairywren.

- M. m. cruentatus occurs across Northern Australia from the Kimberleys to northern Queensland. It is smaller than the nominate subspecies, with males averaging 7.1 g (0.25 oz) and females 6.6 g (0.23 oz) in weight.[14] Males in breeding plumage on Melville Island have a deeper crimson colour to their back.[12] Cruentatus 'bloodstained' is derived from the Latin verb cruentare 'to stain with blood'.[15]

Ewolucja

Ornithologist Richard Schodde has proposed the ancestors of the two subspecies were separated during the last glacial period in the Pleistocene around 12,000 years ago. Aridity had pushed the grasslands preferred by the wren to the north, and with subsequent wetter warmer conditions it once again spread southwards and met the eastern form in northern Queensland and intermediate forms arose.[12] The distribution of the three bi-coloured fairywren species indicates their ancestors lived across New Guinea and northern Australia in a period when sea levels were lower and the two regions were joined by a land bridge. Populations became separated as sea levels rose, and New Guinea birds evolved into the White-shouldered Fairywren, and Australian forms into the Red-backed Fairywren and the arid-adapted White-winged Fairywren.[16]

Opis

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta jest najmniejszym prdstawicielem rodzaju Malurus. Mierzy 11,5 cm i waży 5–10 g, zazwyczaj około 8 g. 6-centymetrowy ogon jest czarny u samców w sezonie godowym, a brązowy pozostałych przedstawicieli gatunku[14]. Mierzący 8,6 cm dziób jest stosunkowo długi, wąski, spiczasty, rozszerzający się przy głowie[17]. Budowa dzioba jest charakterystyczna dla ptaków szukających owadów w ich kryjówkach[18].

Jak u innych chwostek, u tego gatunku występuje dymorfizm płciowy. Samce przybierają swoje ubarwienie godowe w czwartym roku życia, najpóźniej wśród chwostek[19]. Samce w sezonie godowym posiadają czarne ciało i głowę, z wyraźnie odcinającym się czerwonym grzbietem i brązowymi skrzydłami. Przez pozostały okres roku są brązowe, z białym brzuchem. Niektóre samce, zwłaszcza młode, nie zmieniają upierzenia podczas sezonu rozrodczego[20]. Samice są brązowe, z żółtawą plamką pod okiem[21]. Jako jedyne spośród chwostek nie posiadają niebieskiego odcienia na ogonie[22]. Chwostki czerwonogrzbietę potwierdzają Regułę Glogera. Samice są jaśniejsze w cieplejszym klimacie[12] Młode obu płci wyglądają jak samice[23].

Odgłosy

The typical song used by the Red-backed Fairywren to advertise its territory is similar to that of other fairy wrens, namely a reel made up of an introductory note followed by repeated short segments of song, starting weak and soft and ending high and shrill with several syllables. The call is mostly made by the male during mating season.[24][25] Birds will communicate with one another while foraging with a soft ssst, barely audible further than 10–15 m (30–50 ft) away. The alarm call is a high-pitched zit.[14]

Występowanie i środowisko

preferowane środowisko

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta jest ptakiem endemicznym Australii. Zamieszkuje tereny wzdłuż rzek i wybrzeża od Cape Keraudren w północnej Australia Zachodnia, przez Kimberley, Arnhem Land i Gulf Country po rzekę Flinders na południu. Spotykano ją także na wyspach Groote Eylandt, Sir Edmund Pellew, Fraser, Melville i Bathurst Island. Na wszchodnim wybrzezu występuje w Wielkich Górach Wododziałowych po rzekę Hunter[26].

Ptak najchętnie żyje w wilgotnych, porośniętych trawą terenach tropikalnych, lub subtropikalnych, preferowane gatunki traw to Imperata cylindrica i gatunki z rodzajów Sorghum i Eulalia. Gatunek nie migruje, ale może przenosić się z miejsca na miejsce w poszukiwaniu pożywienia, czasami po sezonie godowym opuszcza swoje terytorium[23]. Jeśli teren, na którym występują chwostki jest zagrożony pożarem, ptaki szukają najmniej narażonych na ogień obszarów[27]. Na południu swego występowania chwostka czerwonogrzbieta ustępuje miejsce chwostce białoskrzydłej [28].

Zachowanie

The Red-backed Fairywren is diurnal, and becomes active at dawn and again, in bursts, throughout the day. When not foraging, birds often shelter together. They roost side-by-side in dense cover as well and engage in mutual preening.[29] The usual form of locomotion is hopping, with both feet leaving the ground and landing simultaneously. However, a bird may run when performing the rodent-run display.[30] Its balance is assisted by a relatively long tail, which is usually held upright and is rarely still. The short, rounded wings provide good initial lift and are useful for short flights, though not for extended jaunts.[31] Birds generally fly in a series of undulations for a maximum of 20 or 30 m (60–100 ft)[27]

In dry tall grasslands in monsoonal areas, the change in vegetation may be so great due to either fires or wet season growth that birds may be more nomadic and change territories more than other fairywrens.[27] They form more stable territories elsewhere, such as in coastal areas.[27] Cooperative breeding is less common with this species than with other fairywrens; helper birds have been sporadically reported, but the Red-backed Fairywren has been little studied.[32]

Both the male and female adult Red-backed Fairywren may utilise the rodent-run display to distract predators from nests with young birds. The head, neck and tail are lowered, the wings are held out and the feathers are fluffed as the bird runs rapidly and voices a continuous alarm call.[33]

Pożywienie

Chwostka czerwonogrzbieta, podobnie jak inne chwostki, jest głównie owadożerna. Zjada wiele gatunków insektów, w tym żuki, pluskwiaki, koniki polne, ćmy, osy i cykady. Żywi się równiesz larwami owadów, ich jajami i pająkami. Nasiona i inne części roślin stanowią bardzo niewielki składnik jej diety[34]. Na owady poluje wśród opadłych liści, na krzewach i w pobliżu źródeł wody, zazwyczaj rano i późnym popołudniem. Młode karmią oboje rodzice, jak i pomocnicy[23].

Rozmnażanie

During the mating season, the male moults its brown feathers and displays a fiery red plumage. It may fluff its red back and shoulder feathers out so they cover part of the wings in a puffball-display. It will fly about and confront another male to repel it, or to assert dominance over a female.[32][35] It also picks red petals and sometimes red seeds and presents them to other birds. 90% of the time, the male presents to a female in what appears to be a courtship ritual. The other 10% of the time, it presents to another male in an act of apparent aggression.[36]

Over half the Red-backed Fairywrens in an area can be found in pairs during the mating season. This is apparently a defence against the resource-limited nature of the environment. It is more difficult to maintain a larger interdependent group during dry spells, so the birds try to stay in pairs or smaller groups, which include adults that help parents look after young.[37] Paternity tests have shown that an older male with bright plumage has much more success in the mating season and can mate with more than one female. Accordingly, it has higher sperm storage and makes more mating overtures towards females. A male with browner and less bright plumage or a younger male with bright plumage has a much lower success rate than a bright, older male for mating.[38] Further, an unpaired male serves as a helper to a mated pair in feeding and care of young. When the male pairs his bill darkens, and this happens within three weeks. This is much easier to control than plumage, as moulting takes time and is controlled by seasonality. The bill is vascular and much easier to change in response to the pairings.[39]

The mating season lasts from August to February, and coincides with the arrival of the rainy season in northern Australia. The female does the bulk of the nest building, although the male does assist; this is unusual for the genus Malurus.[35] Concealed in grass tussocks or low shrubs, the spherical nest is constructed of dried grasses and usually lined with smaller, finer grasses and hair.[40] Nests examined in southeast Queensland tended to be larger and untidier than those in northern Australia; the former measured 12–15 cm high by 9–12 cm wide and bore a partly covered 3–6 cm diameter entrance,[41] whereas the latter average around 10–13 cm in height by 6–8 cm wide with a 2–4 cm entrance.[35] Construction takes around one week, and there may be an interval of up to another seven days before eggs are laid.[35] The eggs produced are white with reddish-brown spots in clutches of three to four,[40] and measure 14.5–17 x 10–13 mm; those of subspecies melanocephalus are a little larger than those of cruentatus.[35] The eggs are incubated for two weeks by the female alone. The nestlings are hidden under cover for one week after hatching. The juveniles depend on parents and helpers for approximately one month. They learn to fly between 11–12 days after hatching. Broods hatched earlier in the season will help to raise the broods hatched later on. They will stay as a clutch group for the season after hatching.[23]

Drapieżniki

Dorosłe i młode ptaki padają ofiarami ssaków takich jak kot domowy i lis rudy, a także gryzoni[23] i ptaków drapieżnych. Polują na nie także gady, takie jak warany[42].

Przypisy

- ↑ A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairywrens and Grasswrens), p. 3

- ↑ Richard Bowdler Sharpe: Catalogue of the Passeriformes, or perching birds, in the collection of the British museum. Cichlomorphae, part 1. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1879.

- ↑ Richard Bowdler Sharpe: Catalogue of the Passeriformes, or perching birds, in the collection of the British museum. Cichlomorphae, part 4. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1883.

- ↑ Richard Bowdler Sharpe: A handlist of the genera and species of birds. Volume 4. London: British Museum, 1903.

- ↑ Schodde: Interim List of Australian Songbirds: passerines. Melbourne: RAOU, 1975. OCLC 3546788.

- ↑ FK Barker, Barrowclough GF, Groth JG. A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds; Taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data. „Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B”. 269, s. 295–308, 2002. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1883.

- ↑ FK Barker, Cibois A, Schikler P, Feinstein J, Cracraft J. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. „Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA”. 101 (30), s. 11040–45, 2004. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0401892101. PMID: 15263073. [dostęp 2007-10-12].

- ↑ Relationships within the Australo-Papuan Fairy-wrens (Aves: Malurinae): an evaluation of the utility of allozyme data. „Australian Journal of Zoology”. 45 (2), s. 113–29, 1997. DOI: 10.1071/ZO96068.

- ↑ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 31

- ↑ A revision of the genus Malurus. „Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria”. 8, s. 100–25, 1934.

- ↑ a b c d Schodde (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 107

- ↑ Divergence Across Australia's Carpentarian Barrier: Statistical Phylogeography of the Red-Backed Fairy Wren (Malurus melanocephalus). „Evolution”. 62 (12), s. 3117–34, 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00543.x doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00543.x.

- ↑ a b c Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 182

- ↑ Cassell's Latin Dictionary. Wyd. 5. London: Cassell Ltd., 1979. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 31

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 33

- ↑ Bill size and shape in honeyeaters and other small insectivorous birds in Western Australia. „Australian Journal of Zoology”. 32, s. 657–62, 1984. DOI: 10.1071/ZO9840657.

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 181

- ↑ (abstract) Plumage color and reproduction in the red-backed fairy-wren: Why be a dull breeder?. „Behavioral Ecology”. 19 (3), s. 517–24, 2008. DOI: 10.1093/beheco/arn015.

- ↑ Birds of Australia. Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1973, s. 312. ISBN 0-589-07117-3.

- ↑ A Field Guide to Australian Birds, Volume 2: Passerines. Sydney: Rigby Ltd., 1974, s. 124. ISBN 0-85179-813-6.

- ↑ a b c d e Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, Vol. 5: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats. Oxford University Press: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, s. 161–70. ISBN 0-19-553258-9.

- ↑ Field Guide to Australian Birds. Queensland: Steve Parish Publishing, 2000, s. 224. ISBN 1-876282-10-X.

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 64

- ↑ Schodde (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 100

- ↑ a b c d Schodde (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 105

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Bird Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 179

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 65

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 42

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 41

- ↑ a b Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairywrens and Grasswrens), p. 183

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairywrens and Grasswrens), p. 184

- ↑ Schodde (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 105–06

- ↑ a b c d e Schodde (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 106

- ↑ HTML abstract Testing the function of petal-carrying in the Red-backed Fairy-wren (Malurus melanocephalus). „Emu”. 103 (1), s. 87–92, 2003. DOI: 10.1071/MU01063.

- ↑ Relationship Between Bird-Unit Size and Territory Quality in Three Species of Fairy Wren with Overlapping Territories. „Ecological Research”. 18 (1), s. 73–80, 2003. DOI: 10.1046/j.1440-1703.2003.00534.x.

- ↑ Costs and Benefits of Variable Breeding Plumage in Red-Backed Fairy Wrens. „Evolution”. 56 (8), s. 1673–82, 2002.

- ↑ Changes in Breeding Status are Associated with Rapid Bill Darkening in the Male Red-Backed Fairy-wrens. „Journal of Avian Biology”. 39 (1), s. 81–86, 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04161.x.

- ↑ a b NW Cayley: What Bird is That?. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1959, s. 204. ISBN 0-207-15285-3.

- ↑ Notes on a Trip to the McPherson Range, South-eastern Queensland. „Emu”. 31, s. 48–59, 1931.

- ↑ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 121

Bibliografia

- Ian Rowley: Bird Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-19-854690-4.

- The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae.. Melbourne: Lansdowne Editions, 1982. ISBN 0-7018-1051-3.

External links

- Red-backed Fairywren videos on the Internet Bird Collection