Wikipedia:Wikipedia Signpost/2023-12-24/News and notes

Court of Audit criticizes Italy’s plan to put public domain behind “pay-wall”

The Italian Court of Audit publicly opposed a recent decision by the Ministry of Culture, led by Gennaro Sangiuliano, to establish minimum fees for the production and publication of digital reproductions of cultural heritage, as recently reported by Wikimedia Italia, as well as several national media (in Italian; the latter two links are behind pay-wall).

As written by Italian lawyers Deborah De Angelis and Giuditta Giardini for Communia last July, in Italy the so-called Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code (CCHL) has been in force since 2004; basically, it was intended to "support the role of cultural heritage institutions in sustainable economic and social development", granting them, among other privileges, discretion to choose whether to make art works such as paintings, frescoes and statues available in the public domain, through the attribution of a Creative Commons licence or, at least, the digital reproduction of images.

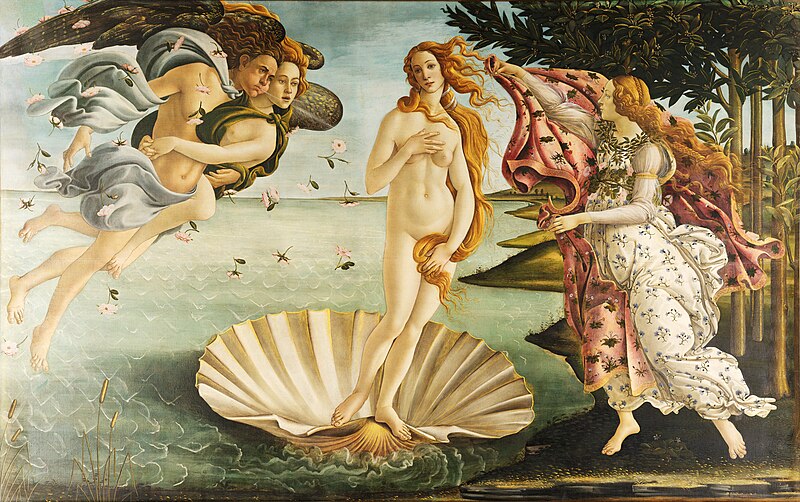

However, in recent years some state-owned institutions have taken advantage of this interpretation of the CCHL to start lawsuits against commercial uses of works by Italian artists which, theoretically, should already be in the public domain – for example, Michelangelo’s David, Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. As explained by De Angelis and Giardini, these initiatives are likely in contrast with the Article 14 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, adopted by the European Union in 2019 and transposed into domestic law by Italy two years later.

In April of this year, the Italian Ministry of Culture caused even more headaches by publishing "guidelines" for the introduction of minimum fees for the commercial use of digital reproductions of state-owned cultural heritage, including works in the public domain (see previous coverage on Diff and the Signpost). The decree, which was harshly criticized by numerous experts and researchers, contradicts the principles expressed both in the CCHL itself – more specifically, the Articles 1 and 6 – and the Faro Convention (which Italy signed and ratified): they stress the importance of full freedom of access to and sharing of reproductions of cultural heritage in the public domain. If officially implemented, the measures included in the MoC’s decree might not only impoverish Wikimedia’s projects, but also damage activities of research and promotion of Italian culture.

Now, though, the Italian Court of Audit also expressed concern about the ministry's bill in a report named The results of monitoring activities done in the year 2022 and the consequential measures adopted by administrations. In their “Review of consequential measures adopted by administrations" – starting from page 157 of the report – the court give credit to the MoC’s offices for their “important effort in digitization”, as for the goals set by the Digital Library and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, while noting how the introduction of the aforementioned minimum fees looks to be “against [this] trend”, especially in regards to the benefits of open access:

For some time now, Open Access has proven to be a powerful multiplier of wealth not only for the cultural institutions themselves [...], but also in terms of increasing the GDP, and is therefore considered a strategic asset for the social, cultural and economic development of the [European] Union’s member countries. [...] The introduction of such a "fee schedule" seems, moreover, to take into account neither the operative peculiarities of the web, nor the potential damage to the community, which should be measured in terms of [...] lost opportunities, as well; therefore, [the decree] also stands in obvious contrast to the clear indications coming from the National Digitization Plan (PND) of cultural heritage.

What’s more, Avvenire and Il Sole 24 Ore (see the links cited at the top of this story) reported that the Court of Audit had already endorsed the free circulation of digital reproductions of cultural heritage in public domain in an October 2022 document, which included the following quote:

The radical transformations digital [devices and services] have produced in our society encourage [...] the abandonment of traditional "proprietary" paradigms, in favor of a more democratic, inclusive and horizontal vision of cultural heritage. Forms of economic return based on the "sale" of the single image appear anachronistic and largely outdated since, moreover, they are patently uneconomic. There is evidence that, in some cases, the ratio of costs incurred in managing the collection service to the actual revenue generated produces a negative balance.

The question is: will the MoC get the memo this time around? – O

Wikimedia Russia to be dissolved

On December 19, 2023, Stas Kozlovsky, the Executive Director of Wikimedia Russia, posted a message on a community page in the Russian Wikipedia, saying that after almost 25 years of work as an associate professor at Moscow State University, he had recently been summoned by the vice-rector and told there was "reliable information" about the imminent intention by Russian authorities to declare him a "foreign agent". He said he was allowed to choose either being dismissed "for absenteeism" or resigning on his own, and eventually "chose the latter" option.

Kozlovsky proceeded to call an emergency meeting of Wikimedia Russia, where he shared this news, and a general decision was taken to close the organization; the liquidation process would take several months.

Stas had taken over as head of Wikimedia Russia earlier this year, after the previous director of the organization, Vladimir V. Medeyko, was indefinitely banned for establishing a government-approved fork of the Russian Wikipedia (see previous Signpost coverage). See the In focus column of this issue for more details on Wikimedia Russia's shut-down, as well as reports from The Moscow Times and Radio Free Europe. – AK, O

Wiki Loves Monuments 2023: a recap

Following the end of the national contests in September and October of this year, the 2023 edition of Wiki Loves Monuments has come to its crucial final phase, and it’s now waiting for the international winners to be publicly announced. Historically, the annual photographic competition organized worldwide by the Wikipedia community has involved dozens of countries across the globe and gifted Wikimedia projects with hundreds of thousands of photos each year; 2023 has made no exception, as users from at least 46 different nations uploaded more than 217,000 images.[1] 2,343 photos became quality images, 46 were assessed as featured pictures, and two received the valued image treatment.

Five countries made their debut in this year’s competition: Egypt, Togo, Uzbekistan, Zambia and the Dutch special municipality of Sint Eustatius. On the other hand, four nations – Belgium, Georgia, Greece and the United States – came back to the party after more or less prolonged hiatus.

Taking a look at the statistics,[2] Italy recorded the highest number of uploaded images by a mile, with 52,004 contributions; to put it in context, that’s almost twice as much as second-placed Russia (28,761), and almost thrice as much as third-placed Ukraine (19,641), as well as a huge jump from the previous performances of the Bel Paese itself. Brazil was the highest-ranked, non-European country on the list, coming in fifth place with 13,202 contributions, right above the United Kingdom (12,851); elsewhere, India led the Asian continent from their 10th place (5,754 images), while Nigeria was the first of the African countries in 17th place (2,800), slightly outperforming the US (2,513).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Italy also topped the chart for the total number of uploaders (946, 565 of whom signed up to Commons during the competition), with Russia (557, 406 of whom registered) and Iran (459, 391 of whom registered) following at moderate distance. It is surprising, however, to see Uganda boast the highest percentage of images that were used in the wikis after being uploaded (about 85%), a feat Egypt (61%) and Malta (44%) are not even close to, despite being on the podium.

Most of the countries involved in Wiki Loves Monuments 2023 have already elected their national winners and/or selected their ten best submissions for the international stage: you can see a comprehensive gallery here.[3] Just like last year, Italy's committee has once again stood out for their decision to “kill two birds with one stone”, by hosting a traditional contest alongside one that was centered around a specific category of monuments, which in this case turned out to be religious buildings; you can see the winners and finalists of the Italian contest in detail here or here. Now, all we have to do is wait for the announcement of the international winners: let’s see which pictures will make our jaws drop this year! – O

- ^ Including 97 from Sint Eustatius and 10 with no specific country tag; a considerable number of images was likely submitted over the deadlines.

- ^ The data for each participating country was updated throughout the whole length of their respective national contests, and halted once they hit their pre-set deadlines.

- ^ The organizers of the Russian contest have decided not to submit any photos for the final round, in sign of respect for the people affected by the persistent Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Brief notes

- Annual reports: Whose Knowledge?, Wikimedia Community User Group Malta, Wiki Movement Brazil User Group.

- Your Wikipedia year in review: A new online tool by User:Jdlrobson allows editors to "look back at all the good work you have been doing this year in helping build the best place on the Internet!", based on their edit history and thanks/thanked log. (A somewhat related feature, focusing on contributions from the last 60 days instead of the last year, was recently integrated into Wikipedia's user interface itself at Special:Impact, see last month's coverage.)

- New administrator: The Signpost welcomes the English Wikipedia's newest administrator, Clovermoss. Her RfA passed on 20 December with 218 in support, 5 opposed, 4 neutral.

- Articles for Improvement: This week's Article for Improvement is Online encyclopedia. Please be bold in helping improve this article! Up next, starting from December 25, will be Carbon source (biology).

Discuss this story

It's a shame that Wikimedia Ru has ceased to exist! Times like these! Happy New Year everyone! ---Zemant (talk) 10:30, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

---Zemant (talk) 10:30, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

The T-shirt is pretty rad, to be honest. :) Clovermoss🍀 (talk) 12:17, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

Pinging Oltrepier, Jayen466, HaeB, and Bri. Is the "Fork" section supposed to have content, or is this some sort of meta-commentary that is going over my head? – Jonesey95 (talk) 13:08, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

Jdlrobson Thank you for this tool: I've just tried, and it looks like a very cool idea! Oltrepier (talk) 18:07, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

If Tails Wx passes nomination, they will have gotten the 13th admin shirt and thus that description will be wrong. ❤HistoryTheorist❤ 23:55, 24 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

- That might depend on your time zone and whether a crat closes the nom right away (sometimes there can be a bit of a delay there). I don't think we have many RfAs that are scheduled to end on New Year's Eve, we'll see if they're the last for 2023 or the first for 2024. :) Clovermoss🍀 (talk) 12:07, 25 December 2023 (UTC)[reply]

I wonder if the Italian MoC is miscalculating how much they'll be able to collect—and how much cultural power paywalls will lose them. According to this 2017 Morsel article, the USDA had also put the Pomological Watercolor Collection behind a paywall to offset the costs of digitization. They never came close to breaking even and after a FOIA request and . Arguably, it has more cultural power as a free, public resource than it ever did gathering dust and obscurity behind a paywall. I know Italy has greater claim to art history than some beautiful botanical illustrations, but the Pomological Watercolor Collection anecdote alone puts doubt in my mind as to how well thought out the MoC proposal is, even from a bloodless and purely profit-driven perspective. Rotideypoc41352 (talk · contribs) 20:17, 7 January 2024 (UTC)[reply]