Wemyss Bay

Wemyss Bay

| |

|---|---|

Pier in front of Wemyss headland and Kelly woods | |

Location within Inverclyde | |

| Population | 2,390 (2022)[2] |

| OS grid reference | NS195695 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WEMYSS BAY |

| Postcode district | PA18 |

| Dialling code | 01475 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

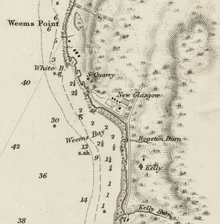

Wemyss Bay (/ˌwiːmz ˈbeɪ/ ) is a village on the coast of the Firth of Clyde in Inverclyde in the west central Lowlands of Scotland. It is in the traditional county of Renfrewshire.[3] It is adjacent to Skelmorlie, North Ayrshire. The town and villages have always been in separate counties, divided by the Kelly Burn.

Wemyss Bay is the port for ferries on the Sea Road to Rothesay on the Isle of Bute. Passengers from the island can connect to Glasgow by trains, which terminate in the town at Wemyss Bay railway station, noted for its architectural qualities and regarded as one of Scotland's finest railway buildings.[4][5] The port is very exposed, so in high winds the ferries must travel up river to Gourock to dock.

Topography

The coast at this place, as it is with a few exceptions along the whole course of the Frith, is bounded at a short distance back from the shore with a range of hills, sometimes rising in gentle slopes, and at other times in abrupt rocky precipices, from which is to be had a continued succession of beautiful and varied views.

— John M. Leighton, Select Views on the River Clyde (1830)[6]

Etymology

The name Kelly comes from Celtic languages, with the meaning of a wood or woodland. Similarly, Kelburn refers to a wooded river.[7]

The name Wemyss is derived from the Scottish Gaelic uaimh which means cave.[8] It is believed to be taken from the caves of the Firth of Forth where the Clan Wemyss made their home. The chiefs are one of the few noble families who are descended from the Celtic nobility through the Clan MacDuff Earls of Fife.[8]

Unlike the Firth of Forth, no conspicuous caves were seen in the Wemyss Bay area, though some minor caves may have been found in the cliffs. In his guide, Boyd says he was told the story that an old fisherman named Robert Wemyss lived at the bay in the 18th century, and rented out boats. Three of his regular customers were unable to agree on the name for the bay, until they decided to "call it after old Bob".[7]

History

Lands of Kelly and Ardgowan

The Kelly Burn flows west down the hillside in a ravine and into the bay, which at one time was called Kelly Bay or White Week.[7] The lands of Kelly, to the north of the burn, were granted in the late 15th century by King James III of Scotland to the Bannatyne family, descendants of the Bannatynes of Kames on Bute. Their Kelly Castle stood on a cliff edge on the north side of the ravine, about 500m upstream from the sea, and was the setting for the song "The Carle of Kellyburn Braes" collected by Robert Burns. The castle burnt down in 1740, and was not rebuilt.[7][9][10]

The land on the north side of the bay to the west of what became the turnpike road, identified as Lower Finnock,[11] was part of the adjoining Shaw Stewart Ardgowan Estate. This densely wooded area had valuable salmon fishing rights, the only dwelling was "Wemyss Cottage" occupied by a fisherman. In the late 18th century, ihe Ardgowan Estate feued an area for houses to Mr. Orkney of Rothesay, who built four identical villas facing the bay, off an access road (Wemyss Bay Road) extending west from the main road; they are shown in John Ainslie's 1796 survey which also records the names Wemyss Bay and Wemyss Point. These villas, the only houses in the bay for many years, were let to Glasgow merchants and came to be known as New Glasgow.[7][12]

Wallace's "marine village"

In 1792 the Glasgow merchant John Wallace, owner of extensive estates in Jamaica with sugar plantations and slaves, bought the Kelly Estate.[13] In 1793 he had a red sandstone mansion called Kelly House built on the hillside up from the road, looking over the bay (this was later painted white).[7][14] About this time the Wemyss Bay Hotel was built on the east side of the main road, near the junction to the road serving the villas;[15][16] a building is shown there on Ainslie's map.[12]

In 1803 his son Robert Wallace of Kelly inherited the Kelly Estate, and began major improvements, including a large picture-gallery extension to Kelly House. In 1814 he exchanged his land at North Finnock with Shaw Stewart of Ardgowan to gain the Lower Finnock area adjoining Wemyss Bay, so that his estate boundary on both sides of the road was on a line immediately north of what became Ardgowan Road. He also bought land which he exchanged with the Earl of Eglinton to extend the Kelly Estate across the Kelly Burn into Ayrshire, incorporating the Auchindarroch area of upper Skelmorlie. In 1832 Wallace became Greenock's first MP, and he played a significant part in introduction of the Uniform Penny Post. He had a row of houses built on the west side of the turnpike road between Inverkip and Wemyss Bay, and named the development Forbes Place after his wife's maiden name, Forbes, of Craigievar.[7][11]

Wallace planned the expansion of Wemyss Bay into a "Marine Village" of 200 villas, with facilities including three churches, hotel, Academy, hot baths, reading room and billiards room, terraced walks featuring a fountain and grass promenade, bowling green, curling pond, and quoiting ground. His plans included a harbour and a steamboat quay.[15][11] In 1846 the Jamaican estates Wallace had inherited were devalued, and he lost his wealth. He resigned as MP,[17][18] and sold the Kelly Estate to an Australian merchant named James Alexander.[7][19]

An 1847 guide book described how "in passing Wemyss Point, we come upon Wemyss Bay or New Glasgow, which from its sheltered situation, the number of beautiful localities admirably adapted for building sites, and which indeed we understand had been purchased of Mr. Wallace by Mr. Alexander, with the view of building villas thereon, will no doubt become an important rival to its neighbouring watering places. There is already a row of neat villas and cottages stretching from the port, and occasionally an elegant mansion. We are now within sight of Kelly House, the seat of R. Wallace, Esq., M.P.".[20][21]

Whiting Bay pier was constructed to the west of the original villas.[22][23] Alexander went bankrupt after only a few years, and in 1850 his creditors sold the estate in two roughly equal portions; Kelly went to James Scott of Glasgow, Wemyss Bay to Charles Wilsone Brown.[7][19]

Wemyss Bay estate and railway

Charles Wilsone Brown did a great deal to develop the bay, selling ground for feuing. By 1855 there were 36 villas, and he got Castle Wemyss, designed by Robert William Billings,[15][24] built on the hillside above Wemyss Point.[25] In 1860 he sold his estate on to George Burns, recently retired as a partner in the Cunard Line.[24] Burns had Wemyss House, designed by James Salmon built (near Undercliff) near the north end of the bay.[26][27] His son John Burns took over Castle Wemyss and had it dramatically enlarged to a design by Billings.[28][29]

In November 1862 work began on the Greenock and Wemyss Bay Railway. The original plan was for a station in the grounds of the "Clutha" villa at the start of Undercliffe Road, with a short walk along to Whiting Bay pier, but objections were raised by the Burns family.[23] James Scott sold ground from the Kelly Estate to the railway,[19] and the line crossed a bridge over the road to extend down the coast over a beach which Wallace's 1845 plan had identified as "Bathing Bay".[11] The railway opened in May 1865 with its stone-built terminus station at a new pier near the Kelly Burn. The Whiting Bay pier had been repaired after damage by a hurricane in February 1856, it was finally wrecked by a storm at the end of 1865.[22]

Further development introduced bigger, more complex, houses. Of the four original villas, two were taken down as the site for a larger house, one replaced by a villa which may have been designed by Billings and was later remodelled by John Honeyman. Only one still shows something of the original design and scale.[30] In 1887 George Burns had the episcopal Inverclyde Church built at Undercliffe Road in memory of his wife. This church was designed by J.J. Burnet.[7][31]

James Young of Kelly

In 1867 Scott sold the Kelly estate to James Young,[19] who had become a wealthy industrialist by inventing paraffin, and was known from then as James Young of Kelly. After his wife Mary died in April 1868,[32] he continued living at Kelly House with his family.[33]

Since college in Glasgow in 1836, Young had been a friend and supporter of David Livingstone.[34] After the news of the explorer's death, he arranged for Livingstone's assistants Chuma and Susi to visit Britain in 1874.[35] They arrived after the funeral, and following a period at Newstead Abbey helping Horace Waller with Livingstone's Last Journals, they reached Kelly in June. Young questioned them closely about the hut in which Livingstone had died, and as grass in fields was similar to that in Africa, they made a facsimile of the one they had built at Ilala. A photo of this informed the book illustrator.[36] They also replicated the kitanda they had made to carry Livingstone after he became too weak to walk. On a later visit to Livingstone's relatives at Hamilton they made another hut.[37] Wrench made a colourised photograph postcard of "Livingstone's Hut, Wemyss Bay".[35][38]

The original Kelly House[14] was replaced by a mansion designed by William Leiper, built further up the hill in 1890. This Kelly House was destroyed in a fire in 1913.[39][40] Attempts were made to blame suffragettes, but research indicates faulty electrical wiring was a more likely cause.[citation needed] The house remained a burnt out ruin for several years. A caravan park now occupies the estate, with its facilities building on the site of the 1890 mansion.[41]

Other notable buildings

A memorial on the shore road recalls 'The Gaiter Club', whose members included Anthony Trollope, Lord Kelvin, Lord Palmerston and the Earl of Shaftesbury.[42]

Neither Castle Wemyss nor James Salmon's Wemyss House remain, having been demolished in the 1980s and 1940s respectively. Also gone is J.J. Burnet's episcopal Inverclyde Church, which stood on the shore road of Undercliff Road and was demolished in 1970.[43]

The Castle Wemyss estate and adjoining areas had been sold off in the 1960s to property developers and since then the village has grown considerably, albeit largely a dormitory settlement for Greenock and Glasgow. However several of the fine red sandstone properties remain and are now seen as renovation opportunities. There is a butcher, newsagent, cafe and fish and chip shop in the village and a pub and cafe in the extensive railway station buildings.

Further reading

Walter Smart's Skelmorlie (1968) provides an account of both Wemyss Bay and Skelmorlie. Gourock, Inverkip and Wemyss Bay from Old Photographs (1981) and Gourock, Inverkip and Wemyss Bay in Old Picture Postcards (1998) are also of interest. All are currently out of print. M.E. Spragg released a book in 2018 called A Walk Through Time at Wemyss Bay.

Notes

- ^ Am Faclair Beag

- ^ "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Registers of Scotland. Publications, leaflets, Land Register Counties. "Registers of Scotland - Leaflets & Guidance". Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Walker, Frank Arneil (1986) The South Clyde Estuary, RIAS.

- ^ Edwards, Brian (1986), Scottish Seaside Towns, BBC Publications

- ^ a b "Kelly House, pp.131-132. – Random Scottish History". Random Scottish History – Pre-1900 Book Collection of Scottish Literature, History, Art & Folklore. (in Latin). 26 May 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Rev John Boyd, M.A. (1879). Guide to Wemyss Bay, Skelmorlie, Inverkip, Largs, and surrounding districts (PDF). Alexander Gardner. Retrieved 28 May 2018. (pdf of sections for Wemyss Bay and Kelly on Inverclyde Council website)

- ^ a b Way, George and Squire, Romily. Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. (Foreword by The Rt Hon. The Earl of Elgin KT, Convenor, The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). Published in 1994. Pages 342 - 343.

- ^ A. Lee (1995). "Kelly Castle". Canmore. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "The Carle of Kellyburn Braes", The Complete Works of Robert Burns, Allan Cunningham (1855)

- ^ a b c d "Plan of the Lands of Kelly, High and Low Finnock and Weyms Bay in the County of Renfrew, and Oakfield in the County of Ayr - Estate Maps, 1750s-1900s". National Library of Scotland - Map Images. 1845. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b John Ainslie (1800). Map of the County of Renfrew. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

Surveyed by John Ainsley in 1796

- ^ 'John Wallace of Cessnock and Kelly', Legacies of British Slave-ownership database, [accessed 21 August 2020].

- ^ a b "View: Renfrewshire V.10 (Innerkip)". Ordnance Survey 25 inch 1st edition, Scotland, surveyed 1856, published 1857. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2020. – 6" 1869

- ^ a b c Monteith & Macdougall 1981, p. 51.

- ^ "View: Renfrewshire V.10 (Innerkip)". Ordnance Survey 25 inch 1st edition, Scotland, surveyed 1856, published 1857. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Monteith & Macdougall 1981, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d "Newspaper Index" (PDF). Inverclyde Council. Watt Library, Greenock. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Sylvan (pseud.) (1847). Sylvan's Pictorial handbook to the Clyde and its watering-places. pp. 47–.

- ^ University Magazine: A Literary and Philosophic Review. Curry. 1851. p. 636.

- ^ a b "Wemyss Bay". Clyde River and Firth. Dalmadan. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b Kelly. "Centennial History of Wemyss Bay's Station and Pier". Friends of Wemyss Bay Station. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b Joseph Irving (1885). The West of Scotland in History: Being Brief Notes Concerning Events, Family Traditions, Topography, and Institutions. R. Forrester. p. 355.

- ^ "View: Renfrewshire V.6 (Innerkip)". Ordnance Survey 25 inch 1st edition, Scotland, surveyed 1856, published 1857. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Monteith & Macdougall 1981, p. 53.

- ^ "Wemyss Bay, Wemyss House". Canmore. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Monteith & Macdougall 1981, p. 52.

- ^ "Wemyss Bay, Castle Wemyss". Canmore. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Wemyss Bay Road, Dunloe and Mansfield, including Boundary Walls and Gatepiers (LB48936)". Historic Environment Scotland. 1 October 2002. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Macleay 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Memorial in Inverkip Cemetery names James Young of Kelly, Mary Young died 5 April 1868

- ^ "James Young (1811–1883)". National Records of Scotland. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Blaikie, William Garden (1881). Life of David Livingstone. Harper Brothers. pp. 20–21.

winter of 1836-37 that he spent his first session in Glasgow. ... While attending Dr. Graham's class he was brought into frequent contact with the assistant to the Professor, Mr. James Young.

(Project Gutenberg eBook) - ^ a b Macleay 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Fraser, Augusta nee (1913). Livingstone and Newstead. J. Murray. pp. 209, 218.

- ^ Clare Pettitt (14 March 2013). Dr Livingstone I Presume: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers and Empire. Profile Books. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-84765-095-5.

- ^ "Photographs and Imagery". Museum of the Scottish Shale Oil Industry. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

PicClick UK, accessed 24 August 2020. - ^ "OS 6" map, revised 1895, published 1898". National Library of Scotland. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ RCAHMS Site Record, Kelly House

- ^ Macleay 2009, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Smart, Walter (1968) Skelmorlie

- ^ Bertie, David M. (2001) Scottish Episcopal Clergy 1689-2000, T&T Clark, p. 658

References

- Macleay, John (2009). Old Inverkip, Wemyss Bay and Skelmorlie. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84033-471-5. OCLC 473437746.

- Monteith, Joy; Macdougall, Sandra (March 1981). Gourock, Inverkip and Wemyss Bay. Greenock: Inverclyde District Libraries. ISBN 0950068721.

- Spragg, M. E. (2018). A Walk Through Time at Wemyss Bay. Greenock: Cartsburn Publishing. ISBN 978-0-244-43987-3.