Wede

| Wede | |

|---|---|

| Weltdeutsch, Weltpitshn, Oiropa'pitshn | |

An extract from Baumann's Weltdeutsch, in Weltdeutsch | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈveːdə], [ˈvɛltdɔʏtʃ], [ˈvɛltpɪtʃn̩] |

| Created by | Adalbert Baumann |

| Date | 1915–28 |

| Purpose | |

| Latin | |

| Sources | German, Yiddish |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

Wede (IPA: [ˈveːdə] ⓘ), Weltdeutsch (IPA: [ˈvɛltdɔʏtʃ] ⓘ), Weltpitshn (IPA: [ˈvɛltpɪtʃn̩]), and Oiropa'pitshn were a series of languages created by Bavarian politician and teacher Adalbert Baumann to create a zonal auxiliary language based on the German language. The first of the languages, Wede (short for Welt-dialekt, World dialect), was published in 1915, with Weltdeutsch, Weltpitshn, and Oiropa'pitshn being published in 1916, 1925, and 1928 respectively. The languages were a posteriori, largely based on the German language – they primarily differed in grammatical and orthographic simplifications. Baumann's languages received a largely negative reception, being mocked by members of the Esperanto and Ido communities; none were implemented in any official manner.

The primary purpose of these languages was to provide a simplified version of German to be easily learnt by foreigners, particularly in the Baltic states and the German colonial empire.[1] Baumann saw previous international auxiliary languages as unsuitable for international communication, in particular criticising their orthographies and source languages. The languages were published via two books and several articles in newspapers.

Creator

Adalbert Baumann was a German gymnasium teacher, politician, and historian. A supporter of Bavarian separatism, he founded the Democratic Socialist Citizen's Party of Munich (German: Demokratisch-sozialistische Bürgerpartei München) in mid-November 1918.[2][3] Baumann promoted the creation of a union state between Austria and Bavaria, on the basis that a peace treaty for a victorious Germany after the First World War would better benefit Bavaria in such a country.[2] Baumann was a member of the Munich branch of the USPD, but quit in mid-1920.[3]

Joining the Nazi Party, Baumann was a proponent for the formation of a German language office; in 1933, he sent a letter to Joseph Goebbels with a plea to establish one, which was denied, and he would later be expelled from the Party in 1937. Contrasting with his German nationalism, Baumann also supported the formation of a European Economic Union of 26 countries; in March 1935, Baumann wrote a letter addressed to the governments of Europe demanding an artificial lingua franca be installed to aid "the economically consolidated Europe". In Baumann's view, the language should be German:

Als solche Hilfssprache kann keine von allen Völkern erst neu zu erlernende Kunstsprache wie das sprachlich und praktisch unsinnige Esperanto in Frage kommen, sondern nur eine vereinfachte, weitestgehende Ableitung von der in Europa verbreitetsten Sprache, das ist die deutsche![4]

English translation: An artificial language such as the linguistically and practically nonsensical Esperanto, which is to be relearned by all peoples, cannot be taken into consideration as such an auxiliary language; only a simplified, extensive derivation of the most widely spoken language in Europe [can], that being German!

History

Wede

In September 1915, Baumann published Wede: the language of understanding for the Central Powers and their Friends, the new World Language (Wede: die Verständigungssprache der Zentralmächte und ihrer Freunde, die neue Welthilfssprache),[i] wherein he outlined his thoughts regarding international auxiliary languages and presented Wede. The name is an abbreviation for "Weltdialekt" (World Dialect), which Baumann shortened in "the American way".[ii]

Baumann believed that the Romance languages (among which he counted English, due to the influence of French on English) had been the dominant world languages throughout the Middle Ages up to the time of writing, partly perpetuated through the use of Latin in the Christian Church and also through the suppression of Germany by France in events such as the Thirty Years' War. Baumann also saw the use of Spanish in the Americas as an example of how Roman influence (as he termed it, Romanismus) still continued to impact the world and Germany.[iii]

Baumann was a critic of previous international languages; Volapük for its excess verb forms (especially its use of an Aorist aspect), excessive minimal pairs, and excessive use of umlauts.[iv] Baumann especially took issue with Esperanto, criticising the circumflexes used in its orthography, supposed monotony, instability, and dearth of speakers.[v] Baumann found the correlative system of the language unacceptable, due to the similarity of the individual correlatives making distinguishing between them in fast speech difficult.[vi] In Baumann's view, a significant reason for the failure of previous language projects was that they were based on the Romance languages, and especially on the dead language of Latin.[5]

Wede was a language created for chauvinistic,[6] nationalist,[7] and imperialist purposes:[8]

... daß Deutschland nach dem unbefangenen Urteile aller Völker das meiste moralische Recht hat, der Welt eine aus seinem Schoße geborene Hilfssprache zu geben, eine Weltsprache ins Germanischem, nicht in romanischem Geiste. English translation: ... that Germany, according to the unbiased judgement of all peoples, has the most moral right to give the world an auxiliary language born from its womb, a world language in the Germanic, not in the Romanic spirit.[vii]

In this, Baumann was not the first – according to German interlinguist Detlev Blanke, Elias Molee's Tutonish was also created for chauvinistic purposes;[9] Sven Werkmeister argues that Wede was a form of linguistic purism, as part of its function was to prevent uncontrolled language change and influence from foreign languages.[10] The language received a negative reception, with Soviet Esperantist Ernest Drezen describing it as "incomprehensible" and remarking that "for the Germans it is nothing but a caricature reminiscent of their own mother tongue" in his Historio de la Mondolingvo (History of the international language).[11]

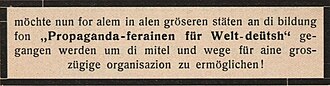

Weltdeutsch

On 16 December 1916, Baumann released a sequel to Wede, entitled Das neue, leichte Weltdeutsch (das verbesserte Wedé) für unsere Bundesgenossen und Freunde! (The new, easy Weltdeutsch (the improved Wedé[note 1]) for our allies and friends!). The book, like its predecessor[viii] was published by Joseph Carl Huber in Munich.[ix]

Baumann created Weltdeutsch as a response to reactions to Wede's orthography, which he intended to simplify in the new language. According to Baumann, the new language was particularly influenced by the comments from a W. Schreiber, Fritz Buckel,[x] and privy councillor[12] Emil Schwörer,[x] who would publish his own German-based auxiliary language, Kolonial-Deutsch, in the same year.[13]

Baumann argued that his language was necessary due to the incoming "world economic war" between Germany and England, claiming that this war could only be won through a political and economic alliance between Germany and the Central and Eastern European powers.[xi] As such an alliance was hindered by the multilingualism of Europe, Baumann designed Wede to be a foreigner-friendly form of the German language.[14] Baumann viewed the international use of French and of English as a factor for the struggle of the Central Powers in the First World War,[xii] citing the use of French in Turkey as the reason for Turkey's supposedly positive relations with France during the war.[12] Additionally, Baumann saw the increasing world population as a threat to the German language, reporting that German had fallen to fourth place among the most spoken languages, behind Chinese.[xiii]

In Baumann's view, one of the largest reasons for this decline was German's difficulty of acquisition: judging by this criterion, he viewed English as surpassing German.[xiii]

Welt'pitshn and Oiropa'pitshn

In 1925, Baumann released another language, Welt'pitshn (lit. 'World pidgin'). Like its predecessors, it received a negative reception, being described in the Esperanto newspaper Sennaciulo as a "result of partisan critics on the territory of international language" ("rezultaĵo de partiecaj kritikemuloj sur la teritorio mondlingva").[15] An article in the February 1926 edition of the Universal Esperanto Association's magazine Esperanto reported that although Baumann had published articles in the press he had no supporters for Welt'pitshn, and called the language a "mutilated German".[16]

Three years later in 1928, Baumann published a fourth language – Oiropa'pitshn (lit. 'European pidgin', abbreviated to "Opi"[17]). Baumann published and promoted it in several newspapers, including the Allgemeine Rundschau of Munich.[18] Although he intended to publish another book on the language, as he had for both Wede and Weltdeutsch, he was unable to find a publisher willing to release the work,[19] despite attempting correspondence with sixty publishing houses.[18][20] Like its predecessors, it was mocked by both Esperantists and Occidentalists,[20] with Johano Koppmann responding in Katolika Mondo:

Ni demandas, kun kia jaro oni volas postuli, ke ĉiuj devas lerni germanajn vortojn, kial ĉiuj ceteraj lingvoj devas esti eligataj el la kunlaboro de l’konstruado de helplingvo? ... Ĉion kuntirante ni opinias senutila, ke unu viro dum 16 jaroj laboregas je problemo jam delonge solvita, depost 50 jaroj.

English translation: We ask, in what year do they want to demand that everyone must learn German words, why must all other languages be excluded from the cooperation of the construction of an auxiliary language? ... Taking everything together, we think it is useless for one man to work for 16 years on a problem that has long been solved, these past 50 years.

— Johann Koppman, 15 June 1928 in Katolika Mundo.[18]

Grammar

Baumann's languages had large grammatical simplifications, with several features of German grammar being removed. Among these was grammatical gender,[21] with Wede now only conjugating articles for grammatical number. This removal also extended to gendered third-person pronouns; German's masculine, feminine and neuter er, sie, and es were all replaced with de.[xiv] Baumann quantified his grammatical simplifications into a set of rules, of which there were 38 for Weltdeutsch and Welt'pitshn,[15] and 25 for Oiropa'pitshn.[20]

Adjective inflection was also removed, with only the ending ⟨-e⟩ remaining for all adjectives in Weltdeutsch,[xv] as in Wede.[xvi] Wede also supported using present participles as adjectives, as well as nominalized adjectives, which were marked with the suffix -s. Wede's degrees of comparison were marked with the suffixes -ere for the comparative and -ste for the superlative, although the latter became -este after singular articles.[xvi] Baumann also removed many of German's prepositions in Weltdeutsch, leaving 27 from German's 54.[1]

Oiropa'pitshn's grammar was largely based on that of English, as Baumann considered it the simplest of modern languages[18] – Julian Prorók, writing in Cosmoglotta, described it as "reforming German in an English fashion" ("reforma german in maniere angles").[20]

Articles

Wede's definite article was t (plural ti),[21] and the indefinite article eine (no plural indefinite article existed).[xvii] Omission of an article was grammatical in several cases, for example after prepositions relating to time and place and in idioms. Articles were also to be omitted after mergers of articles and prepositions (as in übers,[xviii] "above the", from über and das). In Weltdeutsch,[1] Welt'pitshn,[15] and Oiropa'pitshn,[20] the articles were de in the singular and di in the plural. In Weltdeutsch, aine was used as an indefinite article;[1] although English articles were also grammatical, with an being used in front of vowels and a in all other cases (a hund, an apfel).[xix]

Verbs

Wede had two tenses (the present and past,[21] specifically the preterite[xx]), and two auxiliary verbs, hawen and werden. Baumann decided to have a total of four verb forms, from these two tenses in conjunction with the active and passive voices – hawen was used for the active and werden for the passive. Other forms of the two auxiliary verbs were used to create other moods and voices, such as the conditional, which was formed with wirden (German: würden, would).[xx] In Wede, all verbs ended in -en, but this ending could often be dropped. However, there were several exceptions to this rule, such as when the endings were needed for clarity; this was seen for instance in the verbs hawen and gewen.[xxi]

| Tense | Form | Wede | English | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | -en | slagen | to strike | |

| Present Participle | -end | slagend | striking | |

| Past Participle | ge- + stem + -(et) | geslag(et) | struck (or strucken) | Parenthesised endings indicate that their use is optional. |

| Active forms | ||||

| Present | -en | slag(en) | I strike | Vide supra. |

| Preterite | hawen + -et | ik hawen geslag(et) | I have struck | |

| Future | – | ik slag(en) morgen | Tomorrow I will strike | Baumann elected not to create a new conjugation, so future phrases were constructed using specific time phrases. |

| Imperative | Singular: -e

Plural: -en |

slage!

slagen! |

Strike! | |

| Conditional | Present: wirde + infinitive

Past: wirde hawen + past participle |

ik wirde slag(en)

ik wirde hawen geslag(et) |

I would strike

I would have struck |

|

| Optative | meg(en) or welen wir | er meg(en) slag(en) or

welen wir slag(en) |

May he strike! or May we strike! | |

| Passive forms | ||||

| Present | werden + past participle | ik werden geslaget | I am (being) struck | |

| Preterite | worden + past participle | ik worden geslaget | I have been struck | |

| Conditional | wirde + past participle | ik wirde geslaget | I would be struck | |

| Future | – | ik werden geslaget morgen | Tomorrow I'll be struck | Vide supra. |

In Weltdeutsch, Baumann added a third conjugation, the conditional, and further simplified verbs by eliminating forms such as the passive and subjunctive,[xiv] and further reducing irregular verbs.[1] Weltdeutsch's past tense used no auxiliary verb, and had a conjugation following German's imperfect construct. Weltdeutsch's present tense was formed using the language's only auxiliary verb tun conjugated for person, followed by the infinitive form of the verb, although the auxiliary verb was to be omitted in colloquial speech.[xiv] In Weltdeutsch, tmesis of separable verbs was also eliminated: such verbs would be hyphenated instead.[xiv]

| Person | Present | Past | Conditional | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | tu | tat | tät | I do, I did, I would |

| Second | tust | tat-st | tät-st | You do, you did, you would |

| Third | tut | tat | tät | He does, he did, he would |

| Tense | Form | Weltdeutsch | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | conjugated verb tun + infinitive | ich tu komen | I come |

| Past | conjugated verb tun + infinitive | ich tat komen | I came |

Nouns

| Case | Preposition | Wede[xxiii] | Weltdeutsch[xxiv] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | ||

| Nominative | - | t fater | ti fatera | de fater | di fätern |

| Accusative | - | ||||

| Dative | to | ||||

| Genitive | fon | ||||

In Wede, plural nouns used the suffix -a. This replaced any other ending from German; for example, Eltern (parents) became eltera, and Weihnachten (Christmas) became weinagta.Wede's accusative case was identical to its nominative case; the dative case, using the preposition to (a loanword from English), was only used to distinguish direct and indirect objects and for directions, and the genitive, using fon, for showing origin and possession.[xxv] Apart from using fon, the genitive construction could also be expressed using a hyphenated closed compound: for example, t frau fon t haus (lit. 'the woman of the house', German: die Frau des Hauses) could become t haus-frau ('the house-wife', die Hausfrau).[xxiii]

Weltdeutsch's plural nouns ended in -en, except in certain circumstances, such as words ending in -el, -er, or -en. Plural nouns were mostly distinguished via ablaut, usually to umlauted versions (e.g. "au" to "äu"). In both Weltdeutsch and Wede, grammatical case was handled using a system of prepositional complements.[xxiv]

Orthography

Wede included a spelling reform, using an alphabet of 24 letters.[xxvi] From the German alphabet, Baumann removed the letters ⟨v⟩, ⟨c⟩, ⟨j⟩, and substituted ⟨f⟩, ⟨kw⟩, ⟨k⟩, ⟨sh⟩, and ⟨f⟩ for the multigraphs ⟨ph⟩, ⟨qu⟩, ⟨ch⟩, ⟨sch⟩, and ⟨pf⟩.[xxvii] The umlauted letters ⟨ä⟩, ⟨ü⟩, and ⟨ö⟩ were also removed. Baumann considered umlauts to be too great a technical difficulty for foreign printing presses, although ⟨ǝ⟩[note 2] was added to partly replace ⟨ö⟩.[xxvi] Baumann removed the use of silent letters, in particular instances of e and h.[xxviii]

Umlauts reappeared in the orthography of Weltdeutsch, where the digraph ⟨eu⟩ was replaced with ⟨eü⟩ – ⟨Deutschland⟩ (Germany) becomes ⟨Deütschland⟩. The letter é was added to represent a long e. Baumann changed ⟨ei⟩ to ⟨ai⟩, ⟨sch⟩ to ⟨sh⟩ (like in Wede), and the suffix ⟨-end⟩ became ⟨-ent⟩.[xxix] Double letters were replaced with single letter equivalents.[xxx]

Noun capitalization was also removed in Wede and Weltdeutsch,[1] although in Wede this came with several exceptions, such as proper nouns, the word God, and the formal pronoun Si.[xxviii] Baumann changed German's compounds to put hyphens between stems, so the language's exonym ⟨Weltdeutsch⟩, is rendered ⟨Welt-deütsh⟩ in Weltdeutsch.[xxix]

Lexicon

Similarly to controlled natural languages such as Charles Kay Ogden's Basic English, Baumann argued that German's lexicon was too large, and eliminated many synonyms from Weltdeutsch, arguing that only two to three thousand words were necessary for daily life.[1] Weltdeutsch removed several minimal pairs and homophones – for example, der Stiel ("the handle") and der Stil ("the style of writing") became de stil and de sraib-art respectively.[xv]

The languages were a posteriori,[22] being based mostly on High German, although the languages were influenced by German dialects; several vocabulary substitutions came from Low German varieties,[21] and Baumann stated that Middle High German helped eliminate excess consonants.[xxxi] Apart from German, Oiropa'pitshn's vocabulary was partly drawn from Yiddish;[19] in Weltdeutsch, Baumann had thanked the Jews for spreading di deütshe sprache ("the German language") around the world.[xxxii] Baumann further claimed in 1928 that one of the benefits of his language would be that it would be comprehensible to the "Jews of the world who make up the economy".[xxxiii]

See also

- Kolonial-Deutsch, a project for similar purposes by Emil Schwörer

- Language ideology

- Leichte Sprache

- Simplified German

- Weltdeutsch, a previous project by Wilhelm Ostwald

Notes

- ^ Wede is here spelt Wedé due to the new orthography of Weltdeutsch.

- ^ Although in Baumann's Wede this letter is described as a "turned e" (German: umgekehrtes e), Baumann may have been describing and using the letter schwa (ə).

References

Primary

This list of references shows references from Baumann's publications.

- ^ Baumann 1915

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 65

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 7–11

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 30

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 31–41

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 32

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 63

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 1

- ^ Baumann 1916, p. cover

- ^ a b Baumann 1916, p. 3

- ^ Baumann 1916, p. 5

- ^ Baumann 1916, pp. 5–6

- ^ a b Baumann 1916, p. 9

- ^ a b c d e f Baumann 1916, p. 19

- ^ a b Baumann 1916, p. 29

- ^ a b Baumann 1915, p. 91

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 82

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 82–83

- ^ Baumann 1916, p. 18

- ^ a b Baumann 1915, p. 89

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 87–90

- ^ Baumann 1915, pp. 87–89

- ^ a b Baumann 1915, p. 84

- ^ a b Baumann 1916, pp. 18–19

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 83

- ^ a b Baumann 1915, p. 80

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 79

- ^ a b Baumann 1915, p. 81

- ^ a b Baumann 1916, p. 4

- ^ Baumann 1916, p. 28

- ^ Baumann 1915, p. 17

- ^ Baumann 1916, p. 23

- ^ Baumann, Adalbert (1928). "Eine Intereuropäische Hilfssprache in Vorschlag gebracht" [A Proposition for an Inter-European auxiliary language]. Tägliche Omaha Tribüne. Munich: 3 – via Newspapers.com.

Secondary

- ^ a b c d e f g Mühlhäusler, Peter (1 January 1993). "German koines: artificial and natural". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (99): 81–90. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1993.99.81. ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 143448951. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ a b Weber, Thomas (27 October 2017). Becoming Hitler. OUP Oxford. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-19-164179-4. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b Shippard, Richard (2019). "Artists, Intellectuals and the USPD 1917–1922". Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch. N.F., 32.1991 (in German). Duncker & Humblot. p. 204. ISBN 978-3-428-47198-0.

- ^ Gerd, Simon. "Adalbert Baumann: Ein Sprachamt in Europa mit Sitz in München" (PDF) (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Fáy, Tamás (2014). "Vereinfachtes Deutsch als Verständigungssprache" (PDF). Publicationes Universitatis Miskolcinensis Sectio Philosophica. 18 (3): 90–92. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Meyer, Anna-Maria (2014). Wiederbelebung einer Utopie: Probleme und Perspektiven slavischer Plansprachen im Zeitalter des Internets (in German). Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-86309-233-7. OCLC 888462378. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Janton, Pierre (1 January 1993). Esperanto: Language, Literature, and Community. SUNY Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7914-1254-1. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich (1989). "Schwierigkeiten der deutschen Sprachgemeinschaft aufgrund der Dominanz der englischen Sprache". Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft. 8 (2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 260. ISSN 0721-9067 – via De Gruyter.

- ^ Blanke, Detlev; Scharnhorst, Jürgen (2009). Sprachenpolitik und Sprachkultur (in German). Peter Lang. p. 211. ISBN 978-3-631-58579-5. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

Mit oft auf einer einzigen Ethnosprache basierenden Projekten wollten manche Autoren den eigenen Kulturkreis und das in ihm herrschende Sprachmaterial international verbreiten. So war Adalbert Baumann, der Autor von Wede

- ^ Werkmeister, Sven (2010). "¿El alemán como lengua mundial? Anotaciones históricas acerca de un proyecto fallido" [German as a world language? Historical notes on a failed project]. Matices en Lenguas Extranjeras (in Spanish) (4). Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Drezen, Ernest (1931). Historio de la Mondolingvo: Tri Jarcentoj da Serĉado (in Esperanto). Leipzig: EKRELO. p. 144 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Heine, Matthias (26 April 2021). "Leichte Sprache: Siegen im Krieg mit Weltdeutsch und Kolonialdeutsch – WELT". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Mühleisen, Susanne. "Emil Schwörers Kolonial-Deutsch (1916). Sprachliche und historische Anmerkungen zu einem "geplanten Pidgin" im kolonialen Deutsch Südwest Afrika" [Emil Schwörer's Kolonial-Deutsch (1916). Linguistic and historical remarks on a "planned pidgin" in colonial German Southwest Africa]. web.fu-berlin.de (in German). Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Werkmeister, Sven (2004), Honold, Alexander; Scherpe, Klaus R. (eds.), "Die verhinderte Weltsprache: 16. Dezember 1915: Adalbert Baumann präsentiert »Das neue, leichte Weltdeutsch«", Mit Deutschland um die Welt: Eine Kulturgeschichte des Fremden in der Kolonialzeit (in German), Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 464–472, doi:10.1007/978-3-476-02955-3_51, ISBN 978-3-476-02955-3, archived from the original on 11 July 2023, retrieved 15 June 2023

- ^ a b c Meyer, E. (12 November 1925). ""Welt'pitshn"" (PDF). Sennaciulo (in Esperanto). Vol. 2, no. 7. pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Kroniko" [Chronicle]. Esperanto (in Esperanto). No. 2/1926. February 1926. p. 35.

- ^ Krischke, Wolfgang (13 October 2022). Was heißt hier Deutsch?: Kleine Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (in German). C.H.Beck. p. 135. ISBN 978-3-406-79337-0. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Koppmann, Johano (21 June 1928). "Esperanto... En la Ĉifonĉambracon?" (PDF). Katolika Mondo (in Esperanto). Vol. 9, no. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Persatoean bahasa di Europa" [Language in Europe] (PDF). Han Po (in Indonesian). Vol. 3, no. 399. Palembang. 2 November 1928. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Prorók, Julian (October 1928). "Chronica". Cosmoglotta. Vol. 7, no. 10. p. 7. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Adams, Michael (27 October 2011). From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages. OUP Oxford. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-280709-0. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Blanke, Detlev (1989), "Planned languages – a survey of some of the main problems", Interlinguistics, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton, p. 67, doi:10.1515/9783110886115.63, ISBN 9783110886115, archived from the original on 11 July 2023, retrieved 7 May 2023

Bibliography

- Baumann, Adalbert (September 1915). Wede, die Verständigungsprache der Zentralmächte und ihrer Freunde, die neue Welt-Hilfs-Sprache. OCLC 186874750.

- Baumann, Adalbert (16 December 1916). Das neue, leichte Weltdeutsch (das verbesserte Wedé) für unsere Bundesgenossen und Freunde! : seine Notwendigkeit und seine wirtschaftliche Bedeutung ; Vortrag, gehalten am 16. Dezember 1915 im Kaufmännischen Verein München von 1873 ; in laut-shrift geshriben!. Huber. OCLC 634651654.