Walter Defends Sarajevo

| Valter brani Sarajevo | |

|---|---|

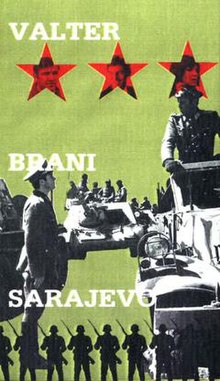

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Hajrudin Krvavac |

| Written by | Đorđe Lebović (main writer) Hajrudin Krvavac Savo Pređo |

| Produced by | Petar Sobajić |

| Starring | Bata Živojinović Ljubiša Samardžić Rade Marković |

| Cinematography | Miroljub Dikosavljević |

| Edited by | Jelena Bjenjaš |

| Music by | Bojan Adamič |

Production company | Bosna Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes |

| Country | Yugoslavia |

| Languages | Serbo-Croatian German |

Walter Defends Sarajevo (Serbo-Croatian: Valter brani Sarajevo / Валтер брани Сарајево) is a 1972 Yugoslav partisan film, directed by Hajrudin Krvavac and starring Bata Živojinović, Ljubiša Samardžić and Rade Marković. The film centres around a mysterious figure named 'Walter', who is actively disrupting the attempts of German commander Alexander Löhr to retreat from the Balkans. The film's eponymous character, Walter, is loosely based around Vladimir Perić, whose nom de guerre was 'Valter'.

Plot

In late 1944, as the end of World War II approaches, the Wehrmacht's high command determines to pull out General Alexander Löhr's Army Group E from the Balkans back to Germany. They plan to supply the tank columns with fuel from a depot in Sarajevo. The Yugoslav partisans' leader in the city, a mysterious man known as Walter, presents a grave danger to the operation's success, and the Germans dispatch Standartenführer von Dietrich of the SD to deal with him. As no one in the city seems to know what Walter even looks like, Dietrich manages to have an operative infiltrate the resistance under the guise of Walter himself. The partisans are caught in a deadly game of betrayal, fraud and imposture while trying to frustrate the Germans' plans.

Ending

At the end of the movie, von Dietrich muses that he has finally realised why he never managed to defeat his nemesis Walter; standing on a hill he points at Sarajevo below and remarks in German: Sehen Sie diese Stadt? Das ist Walter! ("You see that city? That's Walter!") This was intended to send a message of unity consistent with the official politics of the multi-ethnic state of Yugoslavia.

Cast

- Bata Živojinović as Pilot (Walter)

- Ljubiša Samardžić as Zis

- Rade Marković as Sead Kapetanović

- Slobodan Dimitrijević as Suri

- Neda Spasojević as Mirna

- Dragomir Gidra Bojanić as Kondor

- Pavle Vuisić as train dispatcher

- Faruk Begolli as Branko

- Stevo Žigon as Dr Mišković

- Jovan Janićijević as Josic

- Relja Bašić as Obersturmführer

- Hannjo Hasse as Col. von Dietrich

- Rolf Römer as SS-Hauptsturmführer Bischoff

- Fred Delmare as Sgt. Edele (credited as Axel Delmare)

- Herbert Köfer as German general

- Wilhelm Koch-Hooge as Lieutenant Colonel Hagen

- Helmut Schreiber as Lieutenant Colonel Weiland

- Emir Kusturica as a young man

Production

Although not aiming to reflect history, the film's leading character was named after the partisan leader Vladimir Perić, known by his nom de guerre 'Walter', who commanded a resistance group in Sarajevo from 1943 until his death in the battle to liberate the city on April 6, 1945. Hajrudin Krvavac dedicated the picture to the people of Sarajevo and their heroism during the war.[1]

The film marked the beginning of Emir Kusturica's career in cinema. Sixteen years of age at the time, it was his first appearance on film in a small role playing a young communist activist.[2]

Release

The film premiered in Sarajevo on Wednesday, 12 April 1972 in front of 5,000 spectators at the recently built Skenderija Hall. The venue thus hosted another lavish partisan film première, two and a half years after Veljko Bulajić's Battle of Neretva premiered in October 1969. Marshal Josip Broz Tito wasn't in attendance this time, though the premiere still saw its share of Yugoslav celebrities and functionaries including the film's cast as well as the Red Star Belgrade head coach Miljan Miljanić, actress Špela Rozin, Skenderija's director and former Sarajevo mayor Ljubo Kojo,[3] Bosna Film chairman Neđo Parežanin, etc.

Reception

Walter Defends Sarajevo received a favorable response from the Yugoslav audience, especially in Sarajevo itself.[4]

The film was distributed in sixty countries,[5] and achieved its greatest success in the People's Republic of China, becoming the country's most popular foreign film in the 1970s, being viewed by an estimated 300 million people in the year of its release.[6][2] Owing mainly to the Chinese audience, Walter Defends Sarajevo is one of the most watched war films of all time.[7][8]

Legacy

The theme of brotherhood and unity within the Yugoslav population in the face of foreign occupation[4] became a point of reference for the New Primitives' punk sub-culture. Zabranjeno Pušenje, one of the movement's leading bands, named their first album Das ist Walter, in honour of the film.[7]

In mainland China, the movie was so immensely popular that children and streets were named after characters from the film, and a beer brand called 'Walter' was marketed with Velimir Živojinović's picture on the label. As of 2006, it still remains a cult classic in the country.[5] The film also continues to remain a mainstay of diplomatic and economic relations between China and the Western Balkans, with Chinese tourists contributing significantly to local tourism industries, and the implementation of visa-free travel between Bosnia and China.[9][10]

The names of numerous hospitality venues throughout the Balkans (mostly in Bosnia and Serbia) have been inspired by the film.[11]

A museum in Sarajevo dedicated to the film was opened in April 2019.[12]

References

- ^ Levi 2007, pp. 64–66.

- ^ a b Gocić 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Zlatar, Pero (April 1972). "Danas je petak u redakciji Pere Zlatara". Studio. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b Donia 2006, p. 238.

- ^ a b Iordanova 2006, p. 115.

- ^ Cabric, Nemanja (10 August 2012). "Documentary Tells Story of the 'Walter Myth'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ a b Levi 2007, pp. 64–64.

- ^ Hui, Mary (13 April 2019). "China loves this obscure 1972 Yugoslavian movie – and Sarajevo is cashing in". Quartz. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Shopov, Vladimir (1 February 2021). Decade of Patience: How China Became a Power in the Western Balkans (Report). European Council on Foreign Relations. JSTOR resrep29125. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Knezevic, Gordana (29 August 2018). "'Walter' Defended Sarajevo, Now He's Bringing Tourists". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Nekoliko osoba povrijeđeno u tuči ispred sarajevskog puba Walter". Klix.ba. 11 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "Take a Look inside the newly opened 'Valter defends Sarajevo' Museum". Sarajevo Times. 7 April 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Gocić, Goran (2001). Notes from the Underground: The Cinema of Emir Kusturica. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1903364147.

- Donia, Robert J. (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472115570.

- Levi, Pavle (2007). Disintegration in Frames: Aesthetics and Ideology in the Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5368-5.

- Iordanova, Dina (2006). The Cinema of the Balkans. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1904764816.