Wadawurrung

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Wadawurrung, English | |

| Religion | |

| Australian Aboriginal mythology, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Boonwurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung, Wurundjeri see List of Indigenous Australian group names |

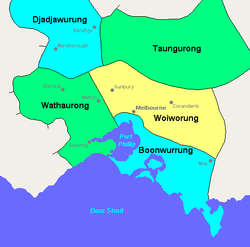

The Wadawurrung nation, also called the Wathaurong, Wathaurung, and Wadda Wurrung, are an Aboriginal Australian people living in the area near Melbourne, Geelong, and the Bellarine Peninsula in the state of Victoria. They are part of the Kulin alliance. The Wathaurong language was spoken by 25 clans south of the Werribee River and the Bellarine Peninsula to Streatham. The area they inhabit has been occupied for at least the last 25,000 years.

Language

Wathaurong is a Pama-Nyungan language, belonging to the Kulin sub-branch of the Kulinic language family.[1]

Country

Wadawurrung territory extended some 7,800 square kilometres (3,000 sq mi). To the east of Geelong their land ran up to Queenscliff, and from the south of Geelong around the Bellarine Peninsula, towards the Otway forests. Its northwestern boundaries lay at Mount Emu and Mount Misery, and extended to Lake Burrumbeet Beaufort and the Ballarat goldfields.[2]

The area they inhabit has been occupied for at least the last 25,000 years, with 140 archaeological sites having been found in the region, indicating significant activity over that period.[3]

Contemporary representation

The Wadawurrung Aboriginal Corporation, a Registered Aboriginal Party since 21 May 2009, represents the traditional owners for the Geelong and Ballarat areas.[1][2][4] The Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative, based in Geelong, also has a role in managing Wadawurrung cultural heritage, for example through its ownership of the Wurdi Youang Aboriginal stone arrangement at Mount Rothwell.[5]

History of contact

William Buckley, a convict who had escaped from the abortive Sullivan Bay settlement in December 1803, lived with a Victorian Aboriginal group, commonly identified with the Wadawurrung.[6][7] In his reminiscences, Buckley tells of his first meeting with native women. Buckley had taken a spear used to mark a grave for use as a walking stick. The women befriended him after recognising the spear as belonging to a relative who had recently died and invited him back to their camp. The tribe thought he was the resurrected Murrangurk, an important former leader.[8][9][a] He was adopted into the band and lived among them for 32 years, being treated with great affection and respect. Buckley states he was appointed a headman and had often witnessed wars, raids, and blood-feuds. He adds that he frequently settled disputes and disarmed warring groups on the eve of some fight.[10][11] As a revered spirit, he was banned from participating in tribal wars. According to Buckley, warfare was a central part of life among Aboriginal people in the area.[12][13]

The European settlement of Wadawurrung territory began in earnest from 1835, with a rapid arrival of squatters around the Geelong area and westwards. This European settlement was marked by Aboriginal resistance to the invasion, often by driving off or stealing sheep, which then resulted in conflict and sometimes a massacre of Aboriginal people.[14]

Very few of the reports of the killing of Aboriginal people were acted upon. On the few occasions the matter did reach court, such as the killing of Woolmudgin on 7 October 1836, following which John Whitehead was sent to Sydney for trial, the case was dropped for lack of evidence and the absconding of key witness Frederick Taylor. At the time Aboriginal people were denied the right to give evidence in courts of law. The incidents listed below are just those cases that have been reported; it is likely other incidents occurred that were never documented officially. Writing on 9 December 1839, Niel Black, a squatter in western Victoria, describes the prevailing attitude of many settlers:

The best way [to procure a run] is to go outside and take up a new run, provided the conscience of the party is sufficiently seared to enable him without remorse to slaughter natives right and left. It is universally and distinctly understood that the chances are very small indeed of a person taking up a new run being able to maintain possession of his place and property without having recourse to such means – sometimes by wholesale....[15]

| Date | Location | Aboriginal people involved | Europeans involved | Aboriginal deaths reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 1803 | Corio Bay | Wadawurrung, possibly Yaawangi or Wadawurrung balug | Lieutenant J Tuckey and others | two people |

| 17 October 1836 | Barwon River, Barrabool Hills | Wadawurrung, balug clan | John Whitehead, encouraged by Frederick Taylor | Woolmudgin, alias Curacoine |

| Summer 1837-1838 | Golf Hill Station, Yarrowee River, north of Inverleigh | Wadawurrung, clan unknown | A shepherd and a hut keeper, Clyde company employees | two people |

| June 1839 – 1840 | unknown | Wadawurrung, barug clan | soldiers | three people |

| 25 November 1847 | Anderson and Mills Public House, Buninyong | Wadawurrung, clan unknown | unknown | two people |

In 1841, Wadawurrung man Bonjon (or "Bon Jon") was charged with murder for killing Yammowing of the Gulidjan people whose territory bordered that of the Wadawurrung. According to the Wesleyan missionary Francis Tuckfield, Bonjon had been in contact with Europeans more than any other member of the Wadawurrung, having been attached to the Border Police for some time. According to the local head of that force, Captain Foster Fyans, Bonjon was with him and his troopers for 4 years, tracking down and assisting in armed confrontations with Aboriginal insurgents in the districts to the west.[17] The prosecution alleged that on or about 14 July 1841, Bonjon shot Yammowing in the head with a carbine at Geelong, killing him.[18][b] The prosecution ultimately abandoned the case and Bonjon was eventually discharged. The case in the Supreme Court of New South Wales for the District of Port Phillip, R v Bonjon, later become notable for the legal question of whether the colonial courts had jurisdiction over offences committed by Aboriginal people inter se, that is, by one Aboriginal person against another, and the legal situation as to the British acquisition of sovereignty over Australia, and its consequences for the Aboriginal people.

The events of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion took place on Wadawurrung land. Three Wadawurrung clans lived in the vicinity of the Eureka diggings: the Burrumbeet baluk at Lakes Burrumbeet and Learmonth, Keyeet baluk, a sub-group of the Burrumbeet baluk, at Mt Buninyong, and the Tooloora baluk, at Mt Warranheip and Lal Lal Creek.[19]

The early policing of the Ballarat Goldfields was done by the Native Police Corps, who enforced the collection of the gold miners licence fee resulting in confrontations between diggers and the Gold Commissioner, considered by some historians, such as Michael Cannon and Weston Bate, as preludes to the Eureka Rebellion.[20]

There is oral history that local Aboriginal people may have looked after some of the children of the Eureka miners after the military storming of the Eureka Stockade and subsequent massacre of miners. Although not corroborated by any written sources, the account has been deemed plausible by historian Ian D. Clark.[21]

Some further credence, although circumstantial, may be provided to the above information. George Yuille, older brother of William Cross Yuille, was not only liked and trusted by the local Aboriginal people, but had also formed a relationship with one of their women. Together they had at least one child, also named George Yuille. George Yuille senior died on 26 March 1854. He was at the time of his death a storekeeper on Specimen Hill and hence he was among the miners. Whether his wife was with him is unknown, but it is a fair assumption that the local Aboriginal people would have been very familiar with the miners, especially if they were in constant contact with George Yuille.

One Learmonth brother in particular was implicitly aware his shepherds were using skulls of Wadawurrung people on stakes to ward people off his property.[22]

Willem Baa Nip was the last surviving member of the Wadawurrung to witness colonisation.[23] A number of prominent Wadawurrung people from the early colonial period, including Baa Nip, are buried in the north-west corner of the Western Cemetery in Geelong.[24]

Historical land use and customs

According to William Buckley, the Wadawurrung practised ritual cannibalism, moderately compared to what he reported of the practices of a neighbouring tribe, the Pallidurgbarran, whose putative cannibalism is itself dubious. Buckley claimed enemies slain in combat were roasted and eaten.[12]

Clans

Before European settlement, 25 separate clans existed, each with a clan headman,[14][c] who was called a n'arweet among the coastal Wadawurrung and a nourenit among the inland northern tribe.[25] N'arweet held the same tribal standing as a ngurungaeta of the Wurundjeri people.

| No | Clan name | Approximate location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barere barere balug | Colac and "Mt Bute" stations |

| 2 | Beerekwart balug | Mount Emu |

| 3 | Bengalat balug | Indented Head |

| 4 | Berrejin balug | Unknown |

| 5 | Boro gundidj | Yarrowee River |

| 6 | Burrumbeet gundidj | Lakes Burumbeet and Learmonth |

| 6a | Keyeet balug | Mount Buninyong |

| 7 | Carringum balug | Carngham |

| 8 | Carininje balug | "Emu Hill" station, Linton's Creek |

| 9 | Corac balug | "Commeralghip" station, and Kuruc-a-ruc Creek |

| 10 | Corrin corrinjer balug | Carranballac |

| 11 | Gerarlture balug | West of Lake Modewarre |

| 12 | Marpeang balug | Blackwood, Myrniong, and Bacchus Marsh |

| 13 | Mear balug | Unknown |

| 14 | Moijerre balug | Mount Emu Creek |

| 15 | Moner balug | "Trawalla" station, Mount Emu Creek |

| 16 | Monmart | Unknown |

| 17 | Neerer balug | Between Geelong and the You Yangs (Hovells Ck?) |

| 18 | Pakeheneek balug | Mount Widderin |

| 19 | Peerickelmoon balug | Mount Misery area between Beaufort and Ballarat |

| 20 | Tooloora balug | Mount Warrenheip, Lal-lal Creek, west branch of Moorabool River. |

| 21 | Woodealloke gundidj | Wardy Yalloak River, south of Kuruc-a-ruc Creek |

| 22 | Wadawurrung balug | Barrabool Hills |

| 23 | Wongerrer balug | Head of Wardy Yalloak River |

| 24 | Worinyaloke balug | West side of Little River |

| 25 | Yaawangi | You Yang Hills |

Alternative names

- Bengali (horde near Geelong)

- Borumbeet Bulluk (horde at Lake Burrambeet speaking a slight dialect)

- Buninyong (place name, location of a northern horde)

- Waddorow, Wadawio, Wadourer, Woddowrong, Wollowurong, Woddowro, Wudjawuru, Witowurrung, Wothowurong, Watorrong

- Wadjawuru, Wuddyawurru, Wuddyawurra, Witouro, Wittyawhuurong

- Wadthaurung, Waitowrung, Wudthaurung, Woddowrong

- Warra, Wardy-yallock (horde in the Pitfield area)

- Witaoro

- Witowro, Witoura

- Wudja-wurung, Witowurung, Witowurong

Source: Tindale 1974

Notes

- ^ "They have a belief, that when they die, they go to some place or other, and are there made white men, and that they then return to this world again for another existence. They think all the white people previous to death were belonging to their own tribes, thus returned to life in a different colour. In cases where they have killed white men, it has generally been because they imagined them to have been originally enemies, or belonging to tribes with whom they were hostile."

- ^ Report is available on Wikisource at:

Port Phillip Patriot, 20 September 1841.

Port Phillip Patriot, 20 September 1841.

- ^ Dawson, citing Clark, writes:"Within the Wathaurong territorial name there is thought to have been from between 14 and 25 smaller clans who traversed a wide area in groups of up to 100 in response to seasonal food sources, ceremonial obligations and trading relationships." (Dawson 2014, p. 83 n.14)

Citations

- ^ "S29: Wadawurrung: Classification". AIATSIS Collection. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Tindale 1974.

- ^ Geelong Australia – Wathaurong People 2007.

- ^ Jones et al. 2016, p. 265.

- ^ Norris et al. 2012, pp. 1–2, 9.

- ^ Russell 2012, p. 175 n.82.

- ^ Lawrence 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Maynard & Haskins 2016, pp. 26–59, 31.

- ^ Morgan 1852, p. 25.

- ^ Howitt 2010, p. 307.

- ^ Morgan 1852, p. 101.

- ^ a b Morgan 1852.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 169.

- ^ a b Clark 1995, pp. 169–175.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Clark 1995, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Bride, Thomas Francis (1898). Letters from Victorian Pioneers. Melbourne: Government Press.

- ^ Port Philip Patriot 1841.

- ^ Clark 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Clark 2004, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Clark 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Whelan 2020.

- ^ City of Greater Geelong 2018.

- ^ "KING JERRY'S TOMB". Geelong Advertiser. No. 21, 886. Victoria, Australia. 29 June 1917. p. 3. Retrieved 7 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Barwick 1984, p. 107.

Sources

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS. 18 June 2021.

- Barwick, Diane E. (1984). "Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835-1904" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 8: 100–131.

- Blake, Barry; Clark, Ian D.; Krishna-Pillay, S.H. (2001) [First published 1998]. "Wathawurrung: the language of the Geelong-Ballarat area". In Blake, Barry (ed.). Wathawurrung and the Colac Language of Southern Victoria. Vol. 147. Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. pp. 59–154. ISBN 0-85883-498-7.

- Clark, Ian D. (1995). Scars in the Landscape: a register of massacre sites in western Victoria, 1803–1859 (PDF). AIATSIS. pp. 169–175. ISBN 0-85575-281-5.

- Clark, Ian D. (2004). Working Paper 2005/2007: Another side of Eureka – the Aboriginal presence on the Ballarat goldfields in 1854 – were Aboriginal people involved in the Eureka rebellion? (PDF). University of Ballarat School of Businbess. pp. 1–17.

- Dawson, Barbara (2014). In the Eye of the Beholder: What Six Nineteenth-century Women Tell Us About Indigenous Authority and Identity. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-1-925-02196-7.

- "Geelong Australia - Wathaurong People". 1 September 2007. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Geelong HERITAGE STRATEGY 2017 - 2021" (PDF). City of Greater Geelong. 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- Howitt, Alfred William (2010) [First published 1904]. The Native Tribes of South-East Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-00632-3.

- Jones, David; Choy, Darryl Low; Clarke, Philip; Serrao-Neumann, Silvia; Hales, Robert; Koschade, Olivia (2016). "The Challenge of Being Heard: Understanding Wadawurrung Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity". In Kennedy, Melissa; Butt, Andrew; Amati, Marco (eds.). Conflict and Change in Australia's Peri-Urban Landscapes, Urban Planning and Environment. Routledge. pp. 260–279. ISBN 978-1-317-16225-4.

- Lawrence, Susan (2000). Dolly's Creek: An Archaeology of a Victorian Goldfields Community. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84912-7.

- Maynard, John; Haskins, Victoria Katharine (2016). Living with the Locals: Early Europeans' Experience of Indigenous Life. National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-27895-1.

- Morgan, John (1852). The Life and Adventures of William Buckley: Thirty-two Years a Wanderer among the Aborigines of the then unexplored country round Port Phillip, now the Province of Victoria (PDF). Hobart: Archibald Macdougall. OCLC 5345532 – via Internet Archive.

- Norris, Ray P.; Norris, Cilla; Hamacher, Duane W.; Abrahams, Reg (28 September 2012). "Wurdi Youang: an Australian Aboriginal stone arrangement with possible solar indications" (PDF). Rock Art Research. 30: 55. arXiv:1210.7000. Bibcode:2013RArtR..30...55N. ISSN 1325-3395.

- Pascoe, Bruce (2007). Convincing Ground: Learning to Fall in Love with Your Country. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-855-75549-2.

- "Report of R v Bonjon". Port Phillip Patriot. Melbourne. 20 September 1841. p. 1.

- Russell, Lynette (2012). Roving Mariners: Australian Aboriginal Whalers and Sealers in the Southern Oceans, 1790–1870. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-438-44425-3.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Wathaurong (VIC)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Whelan, Melanie (11 June 2020). "Statues are toppling globally but what does this mean for Ballarat?". The Courier. Retrieved 13 September 2020.