Waw (letter)

| Waw | |

|---|---|

| Phoenician | 𐤅 |

| Hebrew | ו |

| Aramaic | 𐡅 |

| Syriac | ܘ |

| Arabic | و |

| Phonemic representation | w, v, o, u |

| Position in alphabet | 6 |

| Numerical value | 6 |

| Alphabetic derivatives of the Phoenician | |

| Greek | Ϝ, Υ |

| Latin | F, U, V, W, Y |

| Cyrillic | У, Ѵ |

Waw (wāw "hook") is the sixth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician wāw 𐤅, Aramaic waw 𐡅, Hebrew vav ו, Syriac waw ܘ and Arabic wāw و (sixth in abjadi order; 27th in modern Arabic order).

It represents the consonant [w] in classical Hebrew, and [v] in modern Hebrew, as well as the vowels [u] and [o]. In text with niqqud, a dot is added to the left or on top of the letter to indicate, respectively, the two vowel pronunciations.

It is the origin of Greek Ϝ (digamma) and Υ (upsilon), Cyrillic У and V, Latin F and V and later Y, and the derived Latin- or Roman-alphabet letters U and W.

Origin

The letter likely originated with an Egyptian hieroglyph which represented the word mace (transliterated as ḥḏ, hedj):[1]

| |

A mace was a ceremonial stick or staff, similar to a scepter, perhaps derived from weapons or hunting tools.

In Modern Hebrew, the word וָו vav is used to mean both "hook" and the letter's name (the name is also written וי״ו), while in Syriac and Arabic, waw to mean "hook" has fallen out of use.

Arabic wāw

| wāw | |

|---|---|

| و | |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Arabic script |

| Type | Abjad |

| Language of origin | Arabic language |

| Sound values | /w/, /uː/, /oː/ |

| Alphabetical position | 27 |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Other | |

| Writing direction | Right-to-left |

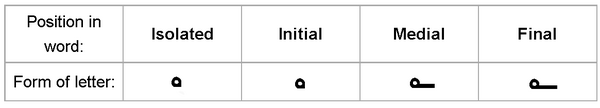

The Arabic letter و is named واو wāw and is written in several ways depending on its position in the word:[2]: I §1

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

و | ـو | ـو | و |

Wāw is used to represent four distinct phonetic features:[2]: I §§1-8

- A consonant, pronounced as a voiced labial-velar approximant /w/, which is the case whenever it is at the beginning of a word, and sometimes elsewhere.

- A long /uː/. The preceding consonant could either have no diacritic or a short-wāw-vowel mark, damma, to aid in the pronunciation by hinting to the following long vowel.

- A long /oː/ in many dialects, as a result of the monophthongization that the diphthong /aw/ underwent in most of words.

- Part of the sequence /aw/. In this case it has no diacritic, but could be marked with a sukun in some traditions. The preceding consonant could either have no diacritic or have a fatḥa sign, hinting to the first vowel /a/ in the diphthong.

As a vowel, wāw can serve as the carrier of a hamza: ؤ. The isolated form of waw (و) is believed to be the origins of the numeral 9.

Wāw is the sole letter of the common Arabic word wa, the primary conjunction in Arabic, equivalent to "and". In writing, it is prefixed to the following word, sometimes including other conjunctions, such as وَلَكِن wa-lākin, meaning "but".[2]: I §365 Another function is the "oath", by preceding a noun of great significance to the speaker. It is often literally translatable to "By..." or "I swear to...", and is often used in the Qur'an in this way, and also in the generally fixed construction والله wallāh ("By Allah!" or "I swear to God!").[2]: I §356d, II §62 The word also appears, particularly in classical verse, in the construction known as wāw rubba, to introduce a description.[2]: II §§84-85

Derived letters

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۋ | ـۋ | ـۋ | ۋ |

With an additional triple dot diacritic above waw, the letter then named ve is used to represent distinctively the consonant /w/ in Arabic-based Uyghur,[3] Kazakh and Kyrgyz.[4]

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۆ | ـۆ | ـۆ | ۆ |

/o/ in Kurdish,[5][6] Beja,[7] and Kashmiri;[8] /v/ in Arabic-based Kazakh;[9] /ø/ in Uyghur.[3]

Thirty-fourth letter of the Azerbaijani Arabic script, represents ü /y/.

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۉ | ـۉ | ـۉ | ۉ |

A variant of Kurdish û وو, ۇ /uː/; historically for Serbo-Croatian /o/.

Also used in Kyrgyz for Үү /y/.

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۈ | ـۈ | ـۈ | ۈ |

/y/ in Uyghur.[3] Also found in Quranic Arabic as in صلۈة ṣalāh "prayer" for an Old Higazi /oː/ merged with /aː/, in modern spelling صلاة.

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۊ | ـۊ | ـۊ | ۊ |

/ʉː/ in Southern Kurdish.[5]

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ۏ | ـۏ | ـۏ | ۏ |

In Jawi script for /v/.[10] Also used in Balochi for /ɯ/ and /oː/.[11]

Other letters

Hebrew waw/vav

| Orthographic variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various print fonts | Cursive Hebrew |

Rashi script | ||

| Serif | Sans-serif | Monospaced | ||

| ו | ו | ו | ||

Hebrew spelling: וָו or וָאו or וָיו.

- The letter appears with or without a hook on different sans-serif fonts, for example

- Arial, DejaVu Sans, Arimo, Open Sans: ו

- Tahoma, Alef, Heebo: ו

Pronunciation in Modern Hebrew

Vav has three orthographic variants, each with a different phonemic value and phonetic realisation:

| Variant (with Niqqud) | Without Niqqud | Name | Phonemic value | Phonetic realisation | English example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ו |

as initial letter:ו |

Consonantal Vav (Hebrew: Vav Itsurit ו׳ עיצורית) |

/v/, /w/ | [v], [w] | vote wall |

| as middle letter:וו | |||||

| as final letter:ו or יו | |||||

|

וּ |

ו |

Vav Shruka ([väv ʃruˈkä] / ו׳ שרוקה) or Shuruq ([ʃuˈruk] / שׁוּרוּק) |

/u/ | [u] | glue |

|

וֹ |

ו |

Vav Chaluma ([väv χäluˈmä] / ו׳ חלומה) or Holam Male ([χo̞ˈläm maˈle̞] / חוֹלָם מָלֵא) |

/o/ | [o̞] | no, noh |

In modern Hebrew, the frequency of the usage of vav, out of all the letters, is one of the highest, about 10.00%.

Vav as consonant

Consonantal vav (ו) generally represents a voiced labiodental fricative (like the English v) in Ashkenazi, European Sephardi, Persian, Caucasian, Italian and modern Israeli Hebrew, and was originally a labial-velar approximant /w/.

In modern Israeli Hebrew, some loanwords, the pronunciation of whose source contains /w/, and their derivations, are pronounced with [w]: ואחד – /ˈwaχad/ (but: ואדי – /ˈvadi/).

Modern Hebrew has no standardized way to distinguish orthographically between [v] and [w]. The pronunciation is determined by prior knowledge or must be derived through context.

Some non standard spellings of the sound [w] are sometimes found in modern Hebrew texts, such as word-initial double-vav: וואללה – /ˈwala/ (word-medial double-vav is both standard and common for both /v/ and /w/, see table above) or, rarely, vav with a geresh: ו׳יליאם – /ˈwiljam/.

Vav with a dot on top

Vav can be used as a mater lectionis for an o vowel, in which case it is known as a ḥolam male, which in pointed text is marked as vav with a dot above it. It is pronounced [o̞] (phonemically transcribed more simply as /o/).

The distinction is normally ignored, and the HEBREW POINT HOLAM (U+05B9) is used in all cases.

The vowel can be denoted without the vav, as just the dot placed above and to the left of the letter it points, and it is then called ḥolam ḥaser. Some inadequate typefaces do not support the distinction between the ḥolam male ⟨וֹ⟩ /o/, the consonantal vav pointed with a ḥolam ḥaser ⟨וֺ⟩ /vo/ (compare ḥolam male ⟨מַצּוֹת⟩ /maˈtsot/ and consonantal vav-ḥolam ḥaser ⟨מִצְוֺת⟩ /mitsˈvot/). To display a consonantal vav with ḥolam ḥaser correctly, the typeface must either support the vav with the Unicode combining character "HEBREW POINT HOLAM HASER FOR VAV" (U+05BA, HTML Entity (decimal) ֺ)[12] or the precomposed character וֹ (U+FB4B).

Compare the three:

- The vav with the combining character HEBREW POINT HOLAM: מִצְוֹת

- The vav with the combining character HEBREW POINT HOLAM HASER FOR VAV: מִצְוֺת

- The precomposed character: מִצְוֹת

Vav with a dot in the middle

Vav can also be used as a mater lectionis for [u], in which case it is known as a shuruk, and in text with niqqud is marked with a dot in the middle (on the left side).

Shuruk and vav with a dagesh look identical ("וּ") and are only distinguishable through the fact that in text with niqqud, vav with a dagesh will normally be attributed a vocal point in addition, e.g. שׁוּק (/ʃuk/), "a market", (the "וּ" denotes a shuruk) as opposed to שִׁוֵּק (/ʃiˈvek/), "to market" (the "וּ" denotes a vav with dagesh and is additionally pointed with a zeire, " ֵ ", denoting /e/). In the word שִׁוּוּק (/ʃiˈvuk/), "marketing", the first ("וּ") denotes a vav with dagesh, the second a shuruk, being the vowel attributed to the first.

When a vav with a dot in the middle comes at the start of a word without a vowel attributed to it, it is a vav conjunctive (see below) that comes before ב, ו, מ, פ, or a letter with a ְ (Shva), and it does the ⟨ʔu⟩ sound.

Numerical value

Vav in gematria represents the number six, and when used at the beginning of Hebrew years, it means 6000 (i.e. ותשנד in numbers would be the date 6754.)

Words written as vav

Vav at the beginning of the word has several possible meanings:

- vav conjunctive (Vav Hachibur, literally "the Vav of Connection" — chibur means "joining", or "bringing together") connects two words or parts of a sentence; it is a grammatical conjunction meaning 'and'. It comes at the start of a word, and is written וּ before ב, ו, מ, פ, or a letter with a ְ (Shva), ו with the following letter's Hataf's Niqqud before a letter with a Hataf (for example, וַ before אֲנִי, וָ before חֳדָשִׁים, וֶ before אֱמֶת), וָ sometimes before a stress and וְ in any other case. This is the most common usage.

- vav consecutive (Vav Hahipuch, literally "the Vav of Reversal" — hipuch means "inversion"), mainly biblical, is commonly mistaken for the previous type of vav; it indicates consequence of actions and reverses the tense of the verb following it:

- when placed in front of a verb in the imperfect tense, it changes the verb to the perfect tense. For example, yomar means 'he will say' and vayomar means 'he said';

- when placed in front of a verb in the perfect, it changes the verb to the imperfect tense. For example, ahavtah means 'you loved', and ve'ahavtah means 'you will love'.

(Note: Older Hebrew did not have "tense" in a temporal sense, "perfect," and "imperfect" instead denoting aspect of completed or continuing action. Modern Hebrew verbal tenses have developed closer to their Indo-European counterparts, mostly having a temporal quality rather than denoting aspect. As a rule, Modern Hebrew does not use the "Vav Consecutive" form.)

Yiddish

In Yiddish,[13] the letter (known as vov) is used for several orthographic purposes in native words:

- Alone, a single vov ו represents the vowel [u] in Northern Yiddish (Litvish) or [i] in Southern Yiddish (Poylish and Galitzish).[citation needed]

- The digraph וו, "tsvey vovn" ('two vovs'), represents the consonant [v].

- The digraph וי, consisting of a vov followed by a yud, represents the diphthong [oj] or [ɛɪ].[citation needed]

The single vov may be written with a dot on the left when necessary to avoid ambiguity and distinguish it from other functions of the letter. For example, the word vu 'where' is spelled וווּ, as tsvey vovn followed by a single vov; the single vov indicating [u] is marked with a dot in order to distinguish which of the three vovs represents the vowel. Some texts instead separate the digraph from the single vov with a silent aleph.

Loanwords from Hebrew or Aramaic in Yiddish are spelled as they are in their language of origin.

Syriac waw

| Waw |

|---|

Madnḫaya Waw Madnḫaya Waw

|

Esṭrangela Waw Esṭrangela Waw

|

Serṭo Waw Serṭo Waw

|

In the Syriac alphabet, the sixth letter is ܘ. Waw (ܘܐܘ) is pronounced [w]. When it is used as a mater lectionis, a waw with a dot above the letter is pronounced [o], and a waw with a dot under the letter is pronounced [u]. Waw has an alphabetic-numeral value of 6.

Character encodings

| Preview | ו | و | ܘ | ࠅ | וּ | וֹ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | HEBREW LETTER VAV | ARABIC LETTER WAW | SYRIAC LETTER WAW | SAMARITAN LETTER BAA | HEBREW LETTER VAV WITH DAGESH | HEBREW LETTER VAV WITH HOLAM | ||||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 1493 | U+05D5 | 1608 | U+0648 | 1816 | U+0718 | 2053 | U+0805 | 64309 | U+FB35 | 64331 | U+FB4B |

| UTF-8 | 215 149 | D7 95 | 217 136 | D9 88 | 220 152 | DC 98 | 224 160 133 | E0 A0 85 | 239 172 181 | EF AC B5 | 239 173 139 | EF AD 8B |

| Numeric character reference | ו |

ו |

و |

و |

ܘ |

ܘ |

ࠅ |

ࠅ |

וּ |

וּ |

וֹ |

וֹ |

| Preview | 𐎆 | 𐡅 | 𐤅 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | UGARITIC LETTER WO | IMPERIAL ARAMAIC LETTER WAW | PHOENICIAN LETTER WAU | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 66438 | U+10386 | 67653 | U+10845 | 67845 | U+10905 |

| UTF-8 | 240 144 142 134 | F0 90 8E 86 | 240 144 161 133 | F0 90 A1 85 | 240 144 164 133 | F0 90 A4 85 |

| UTF-16 | 55296 57222 | D800 DF86 | 55298 56389 | D802 DC45 | 55298 56581 | D802 DD05 |

| Numeric character reference | 𐎆 |

𐎆 |

𐡅 |

𐡅 |

𐤅 |

𐤅 |

References

- ^ Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, T3

- ^ a b c d e W. Wright, A Grammar of the Arabic Language, Translated from the German Tongue and Edited with Numerous Additions and Corrections, 3rd edn by W. Robertson Smith and M. J. de Goeje, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1933 [repr. Beirut: Librairie de Liban, 1996]).

- ^ a b c Johanson, Éva Ágnes Csató; Johanson, Lars, eds. (2003). The Turkic Languages. Taylor & Francis. p. 387. ISBN 978-0-203-06610-2. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31. Retrieved 2023-02-06 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Kyrgyz alphabet, language and pronunciation". omniglot.com. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2021-08-09.

- ^ a b Hussein Ali Fattah. "Ordlista på sydkurdiska Wişename we Kurdî xwarîn" (PDF). p. V. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Unicode Team of KRG-IT. "Kurdish Keyboard". unicode.ekrg.org. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ Wedekind, Klaus; Wedekind, Charlotte; Musa, Abuzeinab (2004–2005). Beja Pedagogical Grammar (PDF). Aswan and Asmara. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Koul, O. N., Raina, S. N., & Bhat, R. (2000). Kashmiri-English Dictionary for Second Language Learners. Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- ^ Minglang Zhou (2003). Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages, 1949-2002. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 149. ISBN 3-11-017896-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Daftar Kata Bahasa Melayu Rumi-Sebutan-Jawi, Dewan Bahasa Pustaka, 5th printing, 2006.

- ^ "Balochi Standarded Alphabet". BalochiAcademy.ir. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "List of fonts that support U+05BA at". Fileformat.info. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2013-04-11.

- ^ Weinreich, Uriel (1992). College Yiddish. New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. pp. 27–8.