Vision rehabilitation

Vision rehabilitation (often called vision rehab) is a term for a medical rehabilitation to improve vision or low vision. In other words, it is the process of restoring functional ability and improving quality of life and independence in an individual who has lost visual function through illness or injury.[1][2] Most visual rehabilitation services are focused on low vision, which is a visual impairment that cannot be fully corrected by regular eyeglasses, contact lenses, medication, or surgery. Low vision interferes with the ability to perform everyday activities.[3] Visual impairment is caused by factors including brain damage, vision loss, and others.[4] Of the vision rehabilitation techniques available, most center on neurological and physical approaches. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, "Provision of, or referral to, vision rehabilitation is now the standard of care for all who experience vision loss.."[5]

Definition

Rehabilitation (literally, the act of making able again) helps patients achieve physical, social, emotional, spiritual independence and quality of life.[6] Rehabilitation does not undo or reverse the cause of damage; it seeks to promote function and independence through adaptation. Individuals can seek rehabilitation in different domains, such as motor rehabilitation after a stroke or physical rehabilitation after a car accident.[7] Low vision can be caused by many diseases.[6]

Clinical studies and treatments

Neurological approach

There are many treatments and therapies to slow degradation of vision loss or improve the vision using neurological approaches. Studies have found that low vision can be restored to good vision.[4][8] In some cases, vision cannot be restored to normal levels but progressive visual loss can be stopped through interventions.[6]

Chemical treatments

In general, chemical treatments are designed to slow the process of vision loss. Some research is done with neuroprotective treatment that will slow the progression of vision loss.[9] Despite other approaches existing, neuroprotective treatments seem to be most common among all chemical treatments.

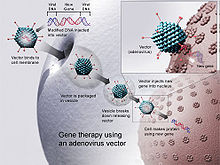

Gene therapy

Gene therapy uses DNA as a delivery system to treat visual impairments. In this approach, DNA is modified through a viral vector, and then cells related to vision cease translating faulty proteins.[10] Gene therapy seems to be the most prominent field that might be able to restore vision through therapy. However, research indicates gene therapy may worsen symptoms, cause them to last longer or lead to further complications.

Physical approach

For physical approaches to vision rehabilitation, most of the training is focused on ways to make environments easier to deal with for those with low vision. Occupational therapy is commonly suggested for these patients.[11] Also, there are devices that help patients achieve higher standards of living. These include video magnifiers, peripheral prism glasses, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), closed-circuit television (CCTV), RFID devices, electronic badges with emergency alert systems, virtual sound systems, and smart wheelchairs.

Mobility training

Mobility training improves the ability for patients with visual impairment to live independently by training patients to become more mobile.[12] For low vision patients, there are multiple mobility training methods and devices available including the 3D sound virtual reality system, talking braille, and RFID floors.

The 3D sound virtual reality system transforms sounds into locations and maps the environment.[13] This system alerts patients to avoid possible dangers. The talking braille is a device that helps low vision patients to read braille by detecting light and transmitting this information through Bluetooth technology.[14] RFID floors are GPS-like navigation systems which help patients to detect building interiors, which ultimately allow them to detour around obstacles.[15]

Home skills training

Home skills training allows patients to improve communication skills, self-care skills, cognitive skills, socialization skills, vocational training, psychological testing, and education.[16] One study indicates that multicomponent group interventions for older adults with low vision as an effective approach related to home training.[17] The multicomponent group interventions include learning new knowledge or skills each week, having multiple sessions to allow participants to apply learned knowledge or skills in their living environment, and building relationships with their health care providers.[18] The most important factor in this intervention is support from family, which includes assistance with changes in lifestyles, financial concerns, and future planning.[19]

Vision Rehabilitation Therapy

The field of vision rehabilitation therapy is made up of professionals who provide specialized services to individuals who are blind or who have a vision loss that cannot be corrected with prescription lenses, medication, or surgery. Professionals who work in this field are called Vision Rehabilitation Therapists[20] (VRTs) or Rehabilitation Teachers[20] (RTs). A vision rehabilitation therapist, VRT, is a professional who provides specialized instruction and guidance to individuals who are blind or have low vision. Best practice recommends professionals who work in this field be nationally certified.[21] To obtain certification as a VRT, professionals must complete a course of study through a university program, complete a 350-hour internship, and pass a certification examination.[22] The certifying body for VRTs is the Academy for Certification of Vision Rehabilitation and Education Professionals, ACVREP.[20] The ACVREP certification for a VRT is called Certified Vision Rehabilitation Therapist and the certified professional uses the letters CVRT indicating this credential. Scope of Practice A VRT works within the scope of practice outlined by ACVREP.[22] The VRT provides Instruction in the use of adaptive skills and strategies to help individuals with vision loss to safely meet their personal goals for employment, education, and independence in the workplace, home, and community. Training from a VRT may include:

- Efficient use of remaining vision

- Safe and independent management of daily living activities, including personal care

- Reading and writing, including braille

- Use of computers, smartphones, tablets, etc., including assistive technology like screen magnifiers and screen readers

- Hobbies and crafts

- Safe movement within the home

- Workplace accommodations

- Recommendations for environmental modifications that increase safety and independence

The VRT serves individuals of any age, whether vision loss is present at birth or if acquired later in life. Individuals with any level of visual impairment, whether partial or total, may benefit from services provided by the VRT. Services provided by a VRT are comprehensive taking into consideration visual abilities, other physical limitations, social supports, and emotional adjustment to vision loss. Instruction with a VRT often uses strategies which include other senses to complete tasks, use of devices that enhance low vision or increase accessibility, and problem-based learning.

Employment

Vision Rehabilitation Therapists are hired by state vocational rehabilitation programs, non-profit agencies, veterans’ administration (VA) hospitals,[23] or they may choose to be self-employed, working as private contractors. A VRT may provide their services one-on-one or in a group setting. Many services are provided in the home of the client with vision loss, so that environmental factors can be assessed, and specific strategies practiced in the location where tasks need to be completed. Services might also be provided in the client’s workplace or educational institution, a community center, rehab residential facility, or in the community. The vision rehabilitation therapist may also work as part of a rehabilitation team, which may include an Orientation and Mobility (O&M) Specialist (COMS), Certified Assistive Technology Instructional Specialist (CATIS), and Low Vision Therapist (CLVT) to provide comprehensive rehabilitation services.

Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapists can assess how low vision affects day-to-day function.[24] They can promote independence in daily activities through home assessments and modifications, problem solving training, home exercise programs and finding compensatory strategies.[25][24] For example, an occupational therapist can suggest adding lighting and contrast to a room to improve visibility.[24]

References

- ^ Brandt Jr, E. N., & Pope, A. M. (Eds.). (1997). Enabling America: Assessing the role of rehabilitation science and engineering. National Academies Press.

- ^ Scheiman, M., Scheiman, M., & Whittaker, S. (2007). Low vision rehabilitation: A practical guide for occupational therapists. SLACK Incorporated.

- ^ Liu, C.J., Brost, M.A., Horton, V.E, Kenyon, S.B., & Mears, K.E. (2013). "Occupational Therapy Interventions to Improve Performance of Daily Activities at Home for Older Adults with Low Vision:A Systematic Review". Journal of Occupational Therapy. 67 (3). PMID 23597685.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fletcher, K., & Barton, J.J.S. (2012). "Vision Rehabilitation: multidisciplinary care of the patient following brain injury". Perception. 41 (10): 1287–1288. doi:10.1068/p4110rvw.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Low Vision - American Academy of Ophthalmology". www.aao.org. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ a b c Vision Rehabilitation for Elderly Individuals with Low Vision or Blindness. USA: Department of Health & Human Services. 2004. p. 20.

- ^ Ponsford, J., Sloan, S., & Snow, P. (2012). Traumatic brain injury: Rehabilitation for everyday adaptive living. Psychology Press.

- ^ Markowitz, S. N. (2006). "Principles of modern low vision rehabilitation". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 41 (3): 289–312. doi:10.1139/i06-027. PMID 16767184.

- ^ Pardue, MT; Phillips, MJ; Yin, H; Sippy, BD; Webb-wood, S; Chow, AY; Ball, SL (2005). "Neuroprotective effect of subretinal implants in the RCS rat". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 46 (2): 674–682. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-0515. PMID 15671299.

- ^ Strachan, T., & Read, A. P. (1999). Gene therapy and other molecular genetic-based therapeutic approaches.

- ^ McGrath, C. E.; Rudman, D. L. (2013). "Factors that influence the occupational engagement of older adults with low vision: a scoping review". British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 76 (5): 234–241. doi:10.4276/030802213x13679275042762. S2CID 147277904.

- ^ Jeon, B.-J.; Cha (2013). "The Effects of Balance of Low Vision Patients on Activities of Daily Living". Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 25 (6): 693–696. doi:10.1589/jpts.25.693. PMC 3804998. PMID 24259832.

- ^ Lentz, T.; Schröder, D.; Vorländer, M.; Assenmacher, I. (2007). "Virtual reality systems with integrated sound field simulation and reproduction". EURASIP Journal on Applied Signal Processing. 2007 (1): 187.

- ^ Ross, D. A., & Lightman, A. (2005, October). Talking braille: a wireless ubiquitous computing network for orientation and way-finding. In Proceedings of the 7th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers and accessibility (pp. 98-105). ACM.

- ^ Mori, T., Suemasu, Y., Noguchi, H., & Sato, T. (2004, October). Multiple people tracking by integrating distributed floor pressure sensors and RFID system. In Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 2004 IEEE International Conference on (Vol. 6, pp. 5271-5278). IEEE.

- ^ Justiss, M. D. (2013). "Occupational Therapy Interventions to Promote Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults With Low Vision: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 67 (3): 296–302. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.005660. PMID 23597687.

- ^ Berger, S.; McAteer, J.; Schreier, K.; Kaldenberg, J. (2013). "Occupational Therapy Interventions to Improve Leisure and Social Participation for Older Adults With Low Vision: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 67 (3): 303–311. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.005447. PMID 23597688.

- ^ Smallfield, S.; Clem, K.; Myers, A. (2013). "Occupational Therapy Interventions to Improve the Reading Ability of Older Adults With Low Vision: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 67 (3): 288–295. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.004929. PMID 23597686.

- ^ O'Connor, P. M.; Lamoureux, E. L.; Keeffe, J. E. (2008). "Predicting the need for low vision rehabilitation services". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 92 (2): 252–255. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.125955. PMID 18227205. S2CID 206867086.

- ^ a b c Lee, Helen; Ottowitz, Jennifer, eds. (2020). Foundations of vision rehabilitation therapy. Louisville: APH Press, American Printing House for the Blind. ISBN 978-1-950723-08-9.

- ^ LeJeune, BJ (May 2018). "Best practices in administration of the OIB program" (PDF). Older Individuals Who are Blind Technical Assistance Center. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b "Vision Rehabilitation Therapy (CVRT) Certification Handbook, Section 2- Scope of Practice". Academy for Certification of Vision Rehabilitation Professionals (ACVREP). March 23, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "VHA HANDBOOK 1174.01" (PDF). Department of Veterans Affairs. February 19, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c Warren, M., & Baker Nobles, L. (2011). Occupational Therapy Services for Persons With Visual Impairment. aota.org. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals/PA/Facts/low-vision.aspx

- ^ Liu, Chiung-ju; Chang, Megan C. (2020-01-01). "Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational Therapy Practice to Improve Performance of Daily Activities for Older Adults With Low Vision: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 74 (1): 7401185010p1–7401185010p18. doi:10.5014/ajot.2020.038372. PMC 7018463. PMID 32078506.