Violence

Violence is often defined as the use of physical force or power by humans to cause harm and degradation to other living beings, such as humiliation, pain, injury, disablement, damage to property and ultimately death, as well as destruction to a society's living environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation."[1]: 5 There is growing recognition among researchers and practitioners of the need to include violence that does not necessarily result in injury or death.[1]: 5

Violence in many forms can be preventable. There is a strong relationship between levels of violence and modifiable factors in a country such as concentrated (regional) poverty, income and gender inequality, the harmful use of alcohol, and the absence of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships between children and parents. Strategies addressing the underlying causes of violence can be relatively effective in preventing violence, although mental and physical health and individual responses, personalities, etc. have always been decisive factors in the formation of these behaviors.[2]

Types

The World Health Organization (WHO) divides violence into three broad categories:[1]

- self-directed violence

- interpersonal violence

- collective violence

This initial categorization differentiates between violence that a person inflicts upon themself, violence inflicted by another individual or by a small group of individuals, and violence inflicted by larger groups such as states, organized political groups, militia groups and terrorist organizations.

Alternatively, violence can primarily be classified as either instrumental or reactive / hostile.[3]

Self-directed

Self-directed violence is subdivided into suicidal behaviour and self-abuse. The former includes suicidal thoughts, attempted suicides—also called para suicide or deliberate self-injury in some countries—and suicide itself. Self-abuse, in contrast, includes acts such as self-mutilation.

Collective

Collective violence is the instrumental use of violence by people who identify themselves as members of a group – whether this group is transitory or has a more permanent identity – against another group or set of individuals in order to achieve political, economic or social objectives.[4]: 82

Unlike the other two broad categories, the subcategories of collective violence suggest possible motives for violence committed by larger groups of individuals or by states. Collective violence that is committed to advance a particular social agenda includes, for example, crimes of hate committed by organized groups, terrorist acts and mob violence. Political violence includes war and related violent conflicts, state violence and similar acts carried out by armed groups. There may be multiple determinants of violence against civilians in such situations.[5] Economic violence includes attacks motivated by economic gain—such as attacks carried out with the purpose of disrupting economic activity, denying access to essential services, or creating economic division and fragmentation. Clearly, acts committed by domestic and subnational groups can have multiple motives.[6] Slow violence is a long-duration form of violence which is often invisible (at least to those not impacted by it), such as environmental degradation, pollution and climate change.[7]

Warfare

War is a state of prolonged violent large-scale conflict involving two or more groups of people, usually under the auspices of government. It is the most extreme form of collective violence.[8] War is fought as a means of resolving territorial and other conflicts, as war of aggression to conquer territory or loot resources, in national self-defence or liberation, or to suppress attempts of part of the nation to secede from it. There are also ideological, religious and revolutionary wars.[9]

Since the Industrial Revolution the lethality of modern warfare has grown. World War I casualties were over 40 million and World War II casualties were over 70 million.

Interpersonal

Interpersonal violence is divided into two subcategories: Family and intimate partner violence—that is, violence largely between family members and intimate partners, usually, though not exclusively, taking place in the home. Community violence—violence between individuals who are unrelated, and who may or may not know each other, generally taking place outside the home. The former group includes forms of violence such as child abuse and child corporal punishment, intimate partner violence and abuse of the elderly. The latter includes youth violence, random acts of violence, rape or sexual assault by strangers, and violence in institutional settings such as schools, workplaces, prisons and nursing homes. When interpersonal violence occurs in families, its psychological consequences can affect parents, children, and their relationship in the short- and long-terms.[10]

Violence against children

Violence against children includes all forms of violence against people under 18 years old, whether perpetrated by parents or other caregivers, peers, romantic partners, or strangers.[11]

Exposure to any form of trauma, particularly in childhood, can increase the risk of mental illness and suicide; smoking, alcohol and substance abuse; chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes and cancer; and social problems such as poverty, crime and violence.[12]

Globally, it is estimated that up to 1 billion children aged 2–17 years, have experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence or neglect in the past year.[11] Most violence against children involves at least one of six main types of interpersonal violence that tend to occur at different stages in a child’s development.[11]

Maltreatment

Maltreatment (including violent punishment) involves physical, sexual and psychological/emotional violence; and neglect of infants, children and adolescents by parents, caregivers and other authority figures, most often in the home but also in settings such as schools and orphanages.

It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other child exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment.[13]

Child maltreatment is a global problem with serious lifelong consequences.[14][pages needed] It is complex and difficult to study.[14][pages needed]

There are no reliable global estimates for the prevalence of child maltreatment. Data for many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, are lacking. Current estimates vary widely depending on the country and the method of research used. Approximately 20% of women and 5–10% of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50% of all children report being physically abused.[1][15]

Consequences of child maltreatment include impaired lifelong physical and mental health, and social and occupational functioning (e.g. school, job, and relationship difficulties). These can ultimately slow a country's economic and social development.[16][17] Preventing child maltreatment before it starts is possible and requires a multisectoral approach. Effective prevention programmes support parents and teach positive parenting skills. Ongoing care of children and families can reduce the risk of maltreatment reoccurring and can minimize its consequences.[18][19]

Bullying

Bullying (including cyber-bullying) is unwanted aggressive behaviour by another child or group of children who are neither siblings nor in a romantic relationship with the victim. It involves repeated physical, psychological or social harm, and often takes place in schools and other settings where children gather, and online.[11]

Youth violence

Following the World Health Organization, youth are defined as people between the ages of 10 and 29 years.[11] Youth violence refers to violence occurring between youths, and includes acts that range from bullying and physical fighting, through more severe sexual and physical assault to homicide.[20][21]

Worldwide some 250,000 homicides occur among youth 10–29 years of age each year, which is 41% of the total number of homicides globally each year ("Global Burden of Disease", World Health Organization, 2008). For each young person killed, 20–40 more sustain injuries requiring hospital treatment.[20] Youth violence has a serious, often lifelong, impact on a person's psychological and social functioning. Youth violence greatly increases the costs of health, welfare and criminal justice services; reduces productivity; decreases the value of property; and generally undermines the fabric of society.[vague]

Prevention programmes shown to be effective or to have promise in reducing youth violence include life skills and social development programmes designed to help children and adolescents manage anger, resolve conflict, and develop the necessary social skills to solve problems; schools-based anti-bullying prevention programmes; and programmes to reduce access to alcohol, illegal drugs and guns.[22] Also, given significant neighbourhood effects on youth violence, interventions involving relocating families to less poor environments have shown promising results.[23] Similarly, urban renewal projects such as business improvement districts have shown a reduction in youth violence.[24]

Different types of youth on youth violence include witnessing or being involved in physical, emotional and sexual abuse (e.g. physical attacks, bullying, rape), and violent acts like gang shootings and robberies. According to researchers in 2018, "More than half of children and adolescents living in cities have experienced some form of community violence." The violence "can also all take place under one roof, or in a given community or neighborhood and can happen at the same time or at different stages of life."[25] Youth violence has immediate and long term adverse impact whether the individual was the recipient of the violence or a witness to it.[26]

Youth violence impacts individuals, their families, and society. Victims can have lifelong injuries which means ongoing doctor and hospital visits, the cost of which quickly add up. Since the victims of youth-on-youth violence may not be able to attend school or work because of their physical and/or mental injuries, it is often up to their family members to take care of them, including paying their daily living expenses and medical bills. Their caretakers may have to give up their jobs or work reduced hours to provide help to the victim of violence. This causes a further burden on society because the victim and maybe even their caretakers have to obtain government assistance to help pay their bills. Recent research has found that psychological trauma during childhood can change a child's brain. "Trauma is known to physically affect the brain and the body which causes anxiety, rage, and the ability to concentrate. They can also have problems remembering, trusting, and forming relationships."[27] Since the brain becomes used to violence it may stay continually in an alert state (similar to being stuck in the fight or flight mode). "Researchers claim that the youth who are exposed to violence may have emotional, social, and cognitive problems. They may have trouble controlling emotions, paying attention in school, withdraw from friends, or show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder".[25]

It is important for youth exposed to violence to understand how their bodies may react so they can take positive steps to counteract any possible short- and long-term negative effects (e.g., poor concentration, feelings of depression, heightened levels of anxiety). By taking immediate steps to mitigate the effects of the trauma they've experienced, negative repercussions can be reduced or eliminated. As an initial step, the youths need to understand why they may be feeling a certain way and to understand how the violence they have experienced may be causing negative feelings and making them behave differently. Pursuing a greater awareness of their feelings, perceptions, and negative emotions is the first step that should be taken as part of recovering from the trauma they have experienced. "Neuroscience research shows that the only way we can change the way we feel is by becoming aware of our inner experience and learning to befriend what is going on inside ourselves".[28]

Some of the ways to combat the adverse effects of exposure to youth violence would be to try various mindfulness and movement activities, deep breathing exercises and other actions that enable youths to release their pent up emotions. Using these techniques will teach body awareness, reduce anxiety and nervousness, and reduce feelings of anger and annoyance.[29]

Youth who have experienced violence benefit from having a close relationship with one or more people.[28] This is important because the trauma victims need to have people who are safe and trustworthy that they can relate and talk to about their horrible experiences. Some youth do not have adult figures at home or someone they can count on for guidance and comfort. Schools in bad neighborhoods where youth violence is prevalent should assign counselors to each student so that they receive regular guidance. In addition to counseling/therapy sessions and programs, it has been recommended that schools offer mentoring programs where students can interact with adults who can be a positive influence on them. Another way is to create more neighborhood programs to ensure that each child has a positive and stable place to go when school in not in session. Many children have benefited from formal organizations now which aim to help mentor and provide a safe environment for the youth especially those living in neighborhoods with higher rates of violence. This includes organizations such as Becoming a Man, CeaseFire Illinois, Chicago Area Project, Little Black Pearl, and Rainbow House".[30] These programs are designed to help give the youth a safe place to go, stop the violence from occurring, offering counseling and mentoring to help stop the cycle of violence. If the youth do not have a safe place to go after school hours they will likely get into trouble, receive poor grades, drop out of school and use drugs and alcohol. The gangs look for youth who do not have positive influences in their life and need protection. This is why these programs are so important for the youth to have a safe environment rather than resorting to the streets.[31]

Intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (or domestic violence) involves physical, sexual and emotional violence by an intimate partner or ex-partner. Although males can also be victims, intimate partner violence disproportionately affects females. It commonly occurs against girls within child marriages and early/forced marriages. Among romantically involved but unmarried adolescents it is sometimes called “dating violence”.[11]

Sexual violence

Sexual violence includes non-consensual completed or attempted sexual contact and acts of a sexual nature not involving contact (such as voyeurism or sexual harassment); acts of sexual trafficking committed against someone who is unable to consent or refuse; and online exploitation.[11]

Emotional or psychological violence

Emotional or psychological violence includes restricting a child’s movements, denigration, ridicule, threats and intimidation, discrimination, rejection and other non-physical forms of hostile treatment.[11]

Intimate partner

Population-level surveys based on reports from victims provide the most accurate estimates of the prevalence of intimate partner violence and sexual violence in non-conflict settings. A study conducted by WHO in 10 mainly developing countries[32] found that, among women aged 15 to 49 years, between 15% (Japan) and 70% (Ethiopia and Peru) of women reported physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner. A growing body of research on men and intimate partner violence focuses on men as both perpetrators and victims of violence, as well as on how to involve men and boys in anti-violence work.[33]

Intimate partner and sexual violence have serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health problems for victims and for their children, and lead to high social and economic costs. These include both fatal and non-fatal injuries, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.[34]

Factors associated with the perpetration and experiencing of intimate partner violence are low levels of education, history of violence as a perpetrator, a victim or a witness of parental violence, harmful use of alcohol, attitudes that are accepting of violence as well as marital discord and dissatisfaction. Factors associated only with perpetration of intimate partner violence are having multiple partners, and antisocial personality disorder.

A recent theory named "The Criminal Spin" suggests a mutual flywheel effect between partners that is manifested by an escalation in the violence.[35] A violent spin may occur in any other forms of violence, but in Intimate partner violence the added value is the mutual spin, based on the unique situation and characteristics of intimate relationship.

The primary prevention strategy with the best evidence for effectiveness for intimate partner violence is school-based programming for adolescents to prevent violence within dating relationships.[36] Evidence is emerging for the effectiveness of several other primary prevention strategies—those that: combine microfinance with gender equality training;[37] promote communication and relationship skills within communities; reduce access to, and the harmful use of alcohol; and change cultural gender norms.[38]

Sexual

Sexual violence is any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against a person's sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object.[39]

Population-level surveys based on reports from victims estimate that between 0.3 and 11.5% of women reported experiencing sexual violence.[40] Sexual violence has serious short- and long-term consequences on physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health for victims and for their children as described in the section on intimate partner violence. If perpetrated during childhood, sexual violence can lead to increased smoking,[41] drug and alcohol misuse, and risky sexual behaviors in later life. It is also associated with perpetration of violence and being a victim of violence.

Many of the risk factors for sexual violence are the same as for domestic violence. Risk factors specific to sexual violence perpetration include beliefs in family honor and sexual purity, ideologies of male sexual entitlement and weak legal sanctions for sexual violence.

Few interventions to prevent sexual violence have been demonstrated to be effective. School-based programmes to prevent child sexual abuse by teaching children to recognize and avoid potentially sexually abusive situations are run in many parts of the world and appear promising, but require further research. To achieve lasting change, it is important to enact legislation and develop policies that protect women; address discrimination against women and promote gender equality; and help to move the culture away from violence.[38]

Elder maltreatment

Elder maltreatment is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person.

While there is little information regarding the extent of maltreatment in elderly populations, especially in developing countries, it is estimated that 4–6% of elderly people in high-income countries have experienced some form of maltreatment at home[42][43] However, older people are often afraid to report cases of maltreatment to family, friends, or to the authorities. Data on the extent of the problem in institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are scarce. Elder maltreatment can lead to serious physical injuries and long-term psychological consequences. Elder maltreatment is predicted to increase as many countries are experiencing rapidly ageing populations.

Many strategies have been implemented to prevent elder maltreatment and to take action against it and mitigate its consequences including public and professional awareness campaigns, screening (of potential victims and abusers), caregiver support interventions (e.g. stress management, respite care), adult protective services and self-help groups. Their effectiveness has, however, not so far been well-established.[44][45]

Targeted

Several rare but painful episodes of assassination, attempted assassination and school shootings at elementary, middle, high schools, as well as colleges and universities in the United States, led to a considerable body of research on ascertainable behaviors of persons who have planned or carried out such attacks. These studies (1995–2002) investigated what the authors called "targeted violence," described the "path to violence" of those who planned or carried out attacks and laid out suggestions for law enforcement and educators. A major point from these research studies is that targeted violence does not just "come out of the blue".[46][47][48][49][50][51]

Everyday

As an anthropological concept, "everyday violence" may refer to the incorporation of different forms of violence (mainly political violence) into daily practices.[52][53] Latin America and the Caribbean, the region with the highest murder rate in the world,[54] experienced more than 2.5 million murders between 2000 and 2017.[55]

Prevalence

Injuries and violence are a significant cause of death and burden of disease in all countries; however, they are not evenly distributed across or within countries.[12] Violence-related injuries kill 1.25 million people every year, as of 2024.[12] This is relatively similar to 2014 (1.3 million people or 2.5% of global mortality), 2013 (1.28 million people) and 1990 (1.13 million people).[4]: 2 [56] For people aged 15–44 years, violence is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, as of 2014.[4]: 2 Between 1990 and 2013, age-standardised death rates fell for self-harm and interpersonal violence.[56]: 139 Of the deaths in 2013, roughly 842,000 were attributed to suicide, 405,000 to interpersonal violence, and 31,000 to collective violence and legal intervention.[56] For each single death due to violence, there are dozens of hospitalizations, hundreds of emergency department visits, and thousands of doctors' appointments.[57] Furthermore, violence often has lifelong consequences for physical and mental health and social functioning and can slow economic and social development. It's particularly the case if it happened in childhood.[12]

In 2013, of the estimated 405,000 deaths due to interpersonal violence globally, assault by firearm was the cause in 180,000 deaths, assault by sharp object was the cause in 114,000 deaths, and the remaining 110,000 deaths from other causes.[56]

Philosophical perspectives

Some philosophers have argued that any interpretation of reality is intrinsically violent.[a] Slavoj Žižek in his book Violence stated that "something violent is the very symbolization of a thing."[citation needed] An ontological perspective considers the harm inflicted by the very interpretation of the world as a form of violence that is distinct from physical violence in that it is possible to avoid physical violence whereas some ontological violence is intrinsic to all knowledge.[b][citation needed]

Both Foucault and Arendt considered the relationship between power and violence but concluded that while related they are distinct.[58]: 46

In feminist philosophy, epistemic violence is the act of causing harm by an inability to understand the conversation of others due to ignorance. Some philosophers think this will harm marginalized groups.[c][citation needed]

Brad Evans states that violence "represents a violation in the very conditions constituting what it means to be human as such", "is always an attack upon a person's dignity, their sense of selfhood, and their future", and "is both an ontological crime ... and a form of political ruination".[60]

Factors and models of understanding

Violence cannot be attributed to solely protective factors or risk factors. Both of these factor groups are equally important in the prevention, intervention, and treatment of violence as a whole. The CDC outlines several risk and protective factors for youth violence at the individual, family, social and community levels.[61]

Individual risk factors include poor behavioral control, high emotional stress, low IQ, and antisocial beliefs or attitudes.[62] Family risk factors include authoritarian childrearing attitudes, inconsistent disciplinary practices, low emotional attachment to parents or caregivers, and low parental income and involvement.[62] Social risk factors include social rejection, poor academic performance and commitment to school, and gang involvement or association with delinquent peers.[62] Community risk factors include poverty, low community participation, and diminished economic opportunities.[62]

On the other hand, individual protective factors include an intolerance towards deviance, higher IQ and GPA, elevated popularity and social skills, as well as religious beliefs.[62] Family protective factors include a connectedness and ability to discuss issues with family members or adults, parent/family use of constructive coping strategies, and consistent parental presence during at least one of the following: when awakening, when arriving home from school, at dinner time, or when going to bed.[62] Social protective factors include quality school relationships, close relationships with non-deviant peers, involvement in prosocial activities, and exposure to school climates that are: well supervised, use clear behavior rules and disciplinary approaches, and engage parents with teachers.[62]

With many conceptual factors that occur at varying levels in the lives of those impacted, the exact causes of violence are complex. To represent this complexity, the ecological, or social ecological model is often used. The following four-level version of the ecological model is often used in the study of violence:

The first level identifies biological and personal factors that influence how individuals behave and increase their likelihood of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence: demographic characteristics (age, education, income), genetics, brain lesions, personality disorders, substance abuse, and a history of experiencing, witnessing, or engaging in violent behaviour.[63][64]

The second level focuses on close relationships, such as those with family and friends. In youth violence, for example, having friends who engage in or encourage violence can increase a young person's risk of being a victim or perpetrator of violence. For intimate partner violence, a consistent marker at this level of the model is marital conflict or discord in the relationship. In elder abuse, important factors are stress due to the nature of the past relationship between the abused person and the care giver.

The third level explores the community context—i.e., schools, workplaces, and neighbourhoods. Risk at this level may be affected by factors such as the existence of a local drug trade, the absence of social networks, and concentrated poverty. All these factors have been shown to be important in several types of violence.

Finally, the fourth level looks at the broad societal factors that help to create a climate in which violence is encouraged or inhibited: the responsiveness of the criminal justice system, social and cultural norms regarding gender roles or parent-child relationships, income inequality, the strength of the social welfare system, the social acceptability of violence, the availability of weapons, the exposure to violence in mass media, and political instability.

Child-rearing

While studies showing associations between physical punishment of children and later aggression cannot prove that physical punishment causes an increase in aggression, a number of longitudinal studies suggest that the experience of physical punishment has a direct causal effect on later aggressive behaviors.[65] Cross-cultural studies have shown that greater prevalence of corporal punishment of children tends to predict higher levels of violence in societies. For instance, a 2005 analysis of 186 pre-industrial societies found that corporal punishment was more prevalent in societies which also had higher rates of homicide, assault, and war.[66] In the United States, domestic corporal punishment has been linked to later violent acts against family members and spouses.[67] The American family violence researcher Murray A. Straus believes that disciplinary spanking forms "the most prevalent and important form of violence in American families", whose effects contribute to several major societal problems, including later domestic violence and crime.[68]

Psychology

The causes of violent behavior in people are often a topic of research in psychology. Neurobiologist Jan Vodka emphasizes that, for those purposes, "violent behavior is defined as overt and intentional physically aggressive behavior against another person."[69]

Based on the idea of human nature, scientists do agree violence is inherent in humans. Among prehistoric humans, there is archaeological evidence for both contentions of violence and peacefulness as primary characteristics.[70]

Since violence is a matter of perception as well as a measurable phenomenon, psychologists have found variability in whether people perceive certain physical acts as "violent". For example, in a state where execution is a legalized punishment we do not typically perceive the executioner as "violent", though we may talk, in a more metaphorical way, of the state acting violently. Likewise, understandings of violence are linked to a perceived aggressor-victim relationship: hence psychologists have shown that people may not recognise defensive use of force as violent, even in cases where the amount of force used is significantly greater than in the original aggression.[71]

The concept of violence normalization is known as socially sanctioned, or structural violence and is a topic of increasing interest to researchers trying to understand violent behavior. It has been discussed at length by researchers in sociology,[72][73] medical anthropology,[74][75] psychology,[76] psychiatry,[77] philosophy,[78] and bioarchaeology.[79][80]

Evolutionary psychology offers several explanations for human violence in various contexts, such as sexual jealousy in humans,[81] child abuse,[82] and homicide.[83] Goetz (2010) argues that humans are similar to most mammal species and use violence in specific situations. He writes that "Buss and Shackelford (1997a) proposed seven adaptive problems our ancestors recurrently faced that might have been solved by aggression: co-opting the resources of others, defending against attack, inflicting costs on same-sex rivals, negotiating status and hierarchies, deterring rivals from future aggression, deterring mate from infidelity, and reducing resources expended on genetically unrelated children."[84]

Goetz writes that most homicides seem to start from relatively trivial disputes between unrelated men who then escalate to violence and death. He argues that such conflicts occur when there is a status dispute between men of relatively similar status. If there is a great initial status difference, then the lower status individual usually offers no challenge and if challenged the higher status individual usually ignores the lower status individual. At the same an environment of great inequalities between people may cause those at the bottom to use more violence in attempts to gain status.[84]

Media

Research into the media and violence examines whether links between consuming media violence and subsequent aggressive and violent behaviour exists. Although some scholars had claimed media violence may increase aggression,[85] this view is coming increasingly in doubt both in the scholarly community[86] and was rejected by the US Supreme Court in the Brown v EMA case, as well as in a review of video game violence by the Australian Government (2010) which concluded evidence for harmful effects were inconclusive at best and the rhetoric of some scholars was not matched by good data.

Mental disorders

Despite public or media opinion, national studies have indicated that severe mental illness does not independently predict future violent behavior, on average, and is not a leading cause of violence in society. There is a statistical association with various factors that do relate to violence (in anyone), such as substance use and various personal, social, and economic factors.[87] A 2015 review found that in the United States, about 4% of violence is attributable to people diagnosed with mental illness,[88] and a 2014 study found that 7.5% of crimes committed by mentally ill people were directly related to the symptoms of their mental illness.[89] The majority of people with serious mental illness are never violent.[90]

In fact, findings consistently indicate that it is many times more likely that people diagnosed with a serious mental illness living in the community will be the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence.[91][92] In a study of individuals diagnosed with "severe mental illness" living in a US inner-city area, a quarter were found to have been victims of at least one violent crime over the course of a year, a proportion eleven times higher than the inner-city average, and higher in every category of crime including violent assaults and theft.[93] People with a diagnosis may find it more difficult to secure prosecutions, however, due in part to prejudice and being seen as less credible.[94]

However, there are some specific diagnoses, such as childhood conduct disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy, which are defined by, or are inherently associated with, conduct problems and violence. There are conflicting findings about the extent to which certain specific symptoms, notably some kinds of psychosis (hallucinations or delusions) that can occur in disorders such as schizophrenia, delusional disorder or mood disorder, are linked to an increased risk of serious violence on average. The mediating factors of violent acts, however, are most consistently found to be mainly socio-demographic and socio-economic factors such as being young, male, of lower socioeconomic status and, in particular, substance use (including alcohol use) to which some people may be particularly vulnerable.[95][91][96][97]

High-profile cases have led to fears that serious crimes, such as homicide, have increased due to deinstitutionalization, but the evidence does not support this conclusion.[97][98] Violence that does occur in relation to mental disorder (against the mentally ill or by the mentally ill) typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions, often in a family setting rather than between strangers.[99] It is also an issue in health care settings[100] and the wider community.[101]Prevention

The threat and enforcement of physical punishment has been a tried and tested method of preventing some violence since civilisation began.[102] It is used in various degrees in most countries.

Public awareness campaigns

Cities and counties throughout the United States organize "Violence Prevention Months" where the mayor, by proclamation, or the county, by a resolution, encourage the private, community and public sectors to engage in activities that raise awareness that violence is not acceptable through art, music, lectures and events. For example, Violence Prevention Month coordinator, Karen Earle Lile in Contra Costa County, California created a Wall of Life, where children drew pictures that were put up in the walls of banks and public spaces, displaying a child's view of violence they had witnessed and how it affected them, in an effort to draw attention to how violence affects the community, not just the people involved.[103]

Interpersonal violence

A review of scientific literature by the World Health Organization on the effectiveness of strategies to prevent interpersonal violence identified the seven strategies below as being supported by either strong or emerging evidence for effectiveness.[104] These strategies target risk factors at all four levels of the ecological model.

Child–caregiver relationships

Among the most effective such programmes to prevent child maltreatment and reduce childhood aggression are the Nurse Family Partnership home-visiting programme[105] and the Triple P (Parenting Program).[106] There is also emerging evidence that these programmes reduce convictions and violent acts in adolescence and early adulthood, and probably help decrease intimate partner violence and self-directed violence in later life.[107][108]

Life skills in youth

Evidence shows that the life skills acquired in social development programmes can reduce involvement in violence, improve social skills, boost educational achievement and improve job prospects. Life skills refer to social, emotional, and behavioural competencies which help children and adolescents effectively deal with the challenges of everyday life.

Gender equality

Evaluation studies are beginning to support community interventions that aim to prevent violence against women by promoting gender equality. For instance, evidence suggests that programmes that combine microfinance with gender equity training can reduce intimate partner violence.[109][110] School-based programmes such as Safe Dates programme in the United States of America[111][112] and the Youth Relationship Project in Canada[113] have been found to be effective for reducing dating violence.

Cultural norms

Rules or expectations of behaviour – norms – within a cultural or social group can encourage violence. Interventions that challenge cultural and social norms supportive of violence can prevent acts of violence and have been widely used, but the evidence base for their effectiveness is currently weak. The effectiveness of interventions addressing dating violence and sexual abuse among teenagers and young adults by challenging social and cultural norms related to gender is supported by some evidence.[114][115]

Support programmes

Interventions to identify victims of interpersonal violence and provide effective care and support are critical for protecting health and breaking cycles of violence from one generation to the next. Examples for which evidence of effectiveness is emerging includes: screening tools to identify victims of intimate partner violence and refer them to appropriate services;[116] psychosocial interventions—such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy—to reduce mental health problems associated with violence, including post-traumatic stress disorder;[117] and protection orders, which prohibit a perpetrator from contacting the victim,[118][119] to reduce repeat victimization among victims of intimate partner violence.

Collective violence

Not surprisingly, scientific evidence about the effectiveness of interventions to prevent collective violence is lacking.[120] However, policies that facilitate reductions in poverty, that make decision-making more accountable, that reduce inequalities between groups, as well as policies that reduce access to biological, chemical, nuclear and other weapons have been recommended. When planning responses to violent conflicts, recommended approaches include assessing at an early stage who is most vulnerable and what their needs are, co-ordination of activities between various players and working towards global, national and local capabilities so as to deliver effective health services during the various stages of an emergency.[121]

Criminal justice

One of the main functions of law is to regulate violence.[122] Sociologist Max Weber stated that the state claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of force to cause harm practised within the confines of a specific territory. Law enforcement is the main means of regulating nonmilitary violence in society. Governments regulate the use of violence through legal systems governing individuals and political authorities, including the police and military. Civil societies authorize some amount of violence, exercised through the police power, to maintain the status quo and enforce laws.

However, German political theorist Hannah Arendt noted: "Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate ... Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defence, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate".[123] Arendt made a clear distinction between violence and power. Most political theorists regarded violence as an extreme manifestation of power whereas Arendt regarded the two concepts as opposites.[124] In the 20th century in acts of democide governments may have killed more than 260 million of their own people through police brutality, execution, massacre, slave labour camps, and sometimes through intentional famine.[125][126]

Violent acts that are not carried out by the military or police and that are not in self-defense are usually classified as crimes, although not all crimes are violent crimes. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) classifies violence resulting in homicide into criminal homicide and justifiable homicide (e.g. self-defense).[127]

The criminal justice approach sees its main task as enforcing laws that proscribe violence and ensuring that "justice is done". The notions of individual blame, responsibility, guilt, and culpability are central to criminal justice's approach to violence and one of the criminal justice system's main tasks is to "do justice", i.e. to ensure that offenders are properly identified, that the degree of their guilt is as accurately ascertained as possible, and that they are punished appropriately. To prevent and respond to violence, the criminal justice approach relies primarily on deterrence, incarceration and the punishment and rehabilitation of perpetrators.[128]

The criminal justice approach, beyond justice and punishment, has traditionally emphasized indicated interventions, aimed at those who have already been involved in violence, either as victims or as perpetrators. One of the main reasons offenders are arrested, prosecuted, and convicted is to prevent further crimes—through deterrence (threatening potential offenders with criminal sanctions if they commit crimes), incapacitation (physically preventing offenders from committing further crimes by locking them up) and through rehabilitation (using time spent under state supervision to develop skills or change one's psychological make-up to reduce the likelihood of future offences).[129]

In recent decades in many countries in the world, the criminal justice system has taken an increasing interest in preventing violence before it occurs. For instance, much of community and problem-oriented policing aims to reduce crime and violence by altering the conditions that foster it—and not to increase the number of arrests. Indeed, some police leaders have gone so far as to say the police should primarily be a crime prevention agency.[130] Juvenile justice systems—an important component of criminal justice systems—are largely based on the belief in rehabilitation and prevention. In the US, the criminal justice system has, for instance, funded school- and community-based initiatives to reduce children's access to guns and teach conflict resolution. Despite this, force is used routinely against juveniles by police.[131] In 1974, the US Department of Justice assumed primary responsibility for delinquency prevention programmes and created the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which has supported the "Blueprints for violence prevention" programme at the University of Colorado Boulder.[132]

Public health

The public health approach is a science-driven, population-based, interdisciplinary, intersectoral approach based on the ecological model which emphasizes primary prevention.[1] Rather than focusing on individuals, the public health approach aims to provide the maximum benefit for the largest number of people, and to extend better care and safety to entire populations. The public health approach is interdisciplinary, drawing upon knowledge from many disciplines including medicine, epidemiology, sociology, psychology, criminology, education and economics. Because all forms of violence are multi-faceted problems, the public health approach emphasizes a multi-sectoral response. It has been proved time and again that cooperative efforts from such diverse sectors as health, education, social welfare, and criminal justice are often necessary to solve what are usually assumed to be purely "criminal" or "medical" problems. The public health approach considers that violence, rather than being the result of any single factor, is the outcome of multiple risk factors and causes, interacting at four levels of a nested hierarchy (individual, close relationship/family, community and wider society) of the Social ecological model.

From a public health perspective, prevention strategies can be classified into three types:

- Primary prevention – approaches that aim to prevent violence before it occurs.

- Secondary prevention – approaches that focus on the more immediate responses to violence, such as pre-hospital care, emergency services or treatment for sexually transmitted infections following a rape.

- Tertiary prevention – approaches that focus on long-term care in the wake of violence, such as rehabilitation and reintegration, and attempt to lessen trauma or reduce long-term disability associated with violence.

A public health approach emphasizes the primary prevention of violence, i.e. stopping them from occurring in the first place. Until recently, this approach has been relatively neglected in the field, with the majority of resources directed towards secondary or tertiary prevention. Perhaps the most critical element of a public health approach to prevention is the ability to identify underlying causes rather than focusing upon more visible "symptoms". This allows for the development and testing of effective approaches to address the underlying causes and so improve health.

The public health approach is an evidence-based and systematic process involving the following four steps:

- Defining the problem conceptually and numerically, using statistics that accurately describe the nature and scale of violence, the characteristics of those most affected, the geographical distribution of incidents, and the consequences of exposure to such violence.

- Investigating why the problem occurs by determining its causes and correlates, the factors that increase or decrease the risk of its occurrence (risk and protective factors) and the factors that might be modifiable through intervention.

- Exploring ways to prevent the problem by using the above information and designing, monitoring and rigorously assessing the effectiveness of programmes through outcome evaluations.

- Disseminating information on the effectiveness of programmes and increasing the scale of proven effective programmes. Approaches to prevent violence, whether targeted at individuals or entire communities, must be properly evaluated for their effectiveness and the results shared. This step also includes adapting programmes to local contexts and subjecting them to rigorous re-evaluation to ensure their effectiveness in the new setting.

In many countries, violence prevention is still a new or emerging field in public health. The public health community has started only recently to realize the contributions it can make to reducing violence and mitigating its consequences. In 1949, Gordon called for injury prevention efforts to be based on the understanding of causes, in a similar way to prevention efforts for communicable and other diseases.[133] In 1962, Gomez, referring to the WHO definition of health, stated that it is obvious that violence does not contribute to "extending life" or to a "complete state of well-being". He defined violence as an issue that public health experts needed to address and stated that it should not be the primary domain of lawyers, military personnel, or politicians.[134]

However, it is only in the last 30 years that public health has begun to address violence, and only in the last fifteen has it done so at the global level.[135] This is a much shorter period of time than public health has been tackling other health problems of comparable magnitude and with similarly severe lifelong consequences.

The global public health response to interpersonal violence began in earnest in the mid-1990s. In 1996, the World Health Assembly adopted Resolution WHA49.25[136] which declared violence "a leading worldwide public health problem" and requested that the World Health Organization (WHO) initiate public health activities to (1) document and characterize the burden of violence, (2) assess the effectiveness of programmes, with particular attention to women and children and community-based initiatives, and (3) promote activities to tackle the problem at the international and national levels. The World Health Organization's initial response to this resolution was to create the Department of Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability and to publish the World report on violence and health (2002).[1]

The case for the public health sector addressing interpersonal violence rests on four main arguments.[137] First, the significant amount of time health care professionals dedicate to caring for victims and perpetrators of violence has made them familiar with the problem and has led many, particularly in emergency departments, to mobilize to address it. The information, resources, and infrastructures the health care sector has at its disposal are an important asset for research and prevention work. Second, the magnitude of the problem and its potentially severe lifelong consequences and high costs to individuals and wider society call for population-level interventions typical of the public health approach. Third, the criminal justice approach, the other main approach to addressing violence (link to entry above), has traditionally been more geared towards violence that occurs between male youths and adults in the street and other public places—which makes up the bulk of homicides in most countries—than towards violence occurring in private settings such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence and elder abuse—which makes up the largest share of non-fatal violence. Fourth, evidence is beginning to accumulate that a science-based public health approach is effective at preventing interpersonal violence.

Human rights

The human rights approach is based on the obligations of states to respect, protect and fulfill human rights and therefore to prevent, eradicate and punish violence. It recognizes violence as a violation of many human rights: the rights to life, liberty, autonomy and security of the person; the rights to equality and non-discrimination; the rights to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment; the right to privacy; and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. These human rights are enshrined in international and regional treaties and national constitutions and laws, which stipulate the obligations of states, and include mechanisms to hold states accountable. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, for example, requires that countries party to the Convention take all appropriate steps to end violence against women. The Convention on the Rights of the Child in its Article 19 states that States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.

Geographical context

Violence, as defined in the dictionary of human geography, "appears whenever power is in jeopardy" and "in and of itself stands emptied of strength and purpose: it is part of a larger matrix of socio-political power struggles".[138] Violence can be broadly divided into three broad categories—direct violence, structural violence and cultural violence.[138] Thus defined and delineated, it is of note, as Hyndman says, that "geography came late to theorizing violence"[138] in comparison to other social sciences. Social and human geography, rooted in the humanist, Marxist, and feminist subfields that emerged following the early positivist approaches and subsequent behavioral turn, have long been concerned with social and spatial justice.[139] Along with critical geographers and political geographers, it is these groupings of geographers that most often interact with violence. Keeping this idea of social/spatial justice via geography in mind, it is worthwhile to look at geographical approaches to violence in the context of politics.

Derek Gregory and Alan Pred assembled the influential edited collection Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror, and Political Violence, which demonstrates how place, space, and landscape are foremost factors in the real and imagined practices of organized violence both historically and in the present.[140] Evidently, political violence often gives a part for the state to play. When "modern states not only claim a monopoly of the legitimate means of violence; they also routinely use the threat of violence to enforce the rule of law",[138] the law not only becomes a form of violence but is violence.[138] Philosopher Giorgio Agamben's concepts of state of exception and homo sacer are useful to consider within a geography of violence. The state, in the grip of a perceived, potential crisis (whether legitimate or not) takes preventative legal measures, such as a suspension of rights (it is in this climate, as Agamben demonstrates, that the formation of the Social Democratic and Nazi government's lager or concentration camp can occur). However, when this "in limbo" reality is designed to be in place "until further notice…the state of exception thus ceases to be referred to as an external and provisional state of factual danger and comes to be confused with juridical rule itself".[141] For Agamben, the physical space of the camp "is a piece of land placed outside the normal juridical order, but it is nevertheless not simply an external space".[141] At the scale of the body, in the state of exception, a person is so removed from their rights by "juridical procedures and deployments of power"[141] that "no act committed against them could appear any longer as a crime";[141] in other words, people become only homo sacer. Guantanamo Bay could also be said to represent the physicality of the state of exception in space, and can just as easily draw man as homo sacer.

In the 1970s, genocides in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot resulted in the deaths of over two million Cambodians (which was 25% of the Cambodian population), forming one of the many contemporary examples of state-sponsored violence.[142] About fourteen thousand of these murders occurred at Choeung Ek, which is the best-known of the extermination camps referred to as the Killing Fields.[142] The killings were arbitrary; for example, a person could be killed for wearing glasses, since that was seen as associating them with intellectuals and therefore as making them part of the enemy. People were murdered with impunity because it was no crime; Cambodians were made homo sacer in a condition of bare life. The Killing Fields—manifestations of Agamben's concept of camps beyond the normal rule of law—featured the state of exception. As part of Pol Pot's "ideological intent…to create a purely agrarian society or cooperative",[142] he "dismantled the country's existing economic infrastructure and depopulated every urban area".[142] Forced movement, such as this forced movement applied by Pol Pot, is a clear display of structural violence. When "symbols of Cambodian society were equally disrupted, social institutions of every kind…were purged or torn down",[142] cultural violence (defined as when "any aspect of culture such as language, religion, ideology, art, or cosmology is used to legitimize direct or structural violence"[138]) is added to the structural violence of forced movement and to the direct violence, such as murder, at the Killing Fields. Vietnam eventually intervened and the genocide officially ended. However, ten million landmines left by opposing guerillas in the 1970s[142] continue to create a violent landscape in Cambodia.

Human geography, though coming late to the theorizing table, has tackled violence through many lenses, including anarchist geography, feminist geography, Marxist geography, political geography, and critical geography. However, Adriana Cavarero notes that, "as violence spreads and assumes unheard-of forms, it becomes difficult to name in contemporary language".[143] Cavarero proposes that, in facing such a truth, it is prudent to reconsider violence as "horrorism"; that is, "as though ideally all the…victims, instead of their killers, ought to determine the name".[143] With geography often adding the forgotten spatial aspect to theories of social science, rather than creating them solely within the discipline, it seems that the self-reflexive contemporary geography of today may have an extremely important place in this current (re)imaging of violence, exemplified by Cavarero.[clarification needed]

Epidemiology

As of 2010, all forms of violence resulted in about 1.34 million deaths up from about 1 million in 1990.[145] Suicide accounts for about 883,000, interpersonal violence for 456,000 and collective violence for 18,000.[145] Deaths due to collective violence have decreased from 64,000 in 1990.[145]

By way of comparison, the 1.5 millions deaths a year due to violence is greater than the number of deaths due to tuberculosis (1.34 million), road traffic injuries (1.21 million), and malaria (830'000), but slightly less than the number of people who die from HIV/AIDS (1.77 million).[146]

For every death due to violence, there are numerous nonfatal injuries. In 2008, over 16 million cases of non-fatal violence-related injuries were severe enough to require medical attention. Beyond deaths and injuries, forms of violence such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and elder maltreatment have been found to be highly prevalent.

Self-directed violence

In the last 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60% worldwide.[147] Suicide is among the three leading causes of death among those aged 15–44 years in some countries, and the second leading cause of death in the 10–24 years age group.[148] These figures do not include suicide attempts which are up to 20 times more frequent than suicide.[147] Suicide was the 16th leading cause of death worldwide in 2004 and is projected to increase to the 12th in 2030.[149] Although suicide rates have traditionally been highest among the male elderly, rates among young people have been increasing to such an extent that they are now the group at highest risk in a third of countries, in both developed and developing countries.[150]

Interpersonal violence

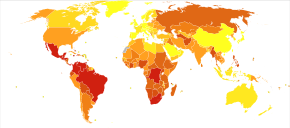

Rates and patterns of violent death vary by country and region. In recent years, homicide rates have been highest in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean and lowest in East Asia, the western Pacific, and some countries in northern Africa.[151] Studies show a strong, inverse relationship between homicide rates and both economic development and economic equality. Poorer countries, especially those with large gaps between the rich and the poor, tend to have higher rates of homicide than wealthier countries. Homicide rates differ markedly by age and sex. Gender differences are least marked for children. For the 15 to 29 age group, male rates were nearly six times those for female rates; for the remaining age groups, male rates were from two to four times those for females.[152]

Studies in a number of countries show that, for every homicide among young people age 10 to 24, 20 to 40 other young people receive hospital treatment for a violent injury.[1]

Forms of violence such as child maltreatment and intimate partner violence are highly prevalent. Approximately 20% of women and 5–10% of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50% of all children report being physically abused.[153] A WHO multi-country study found that between 15 and 71% of women reported experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.[154]

Collective violence

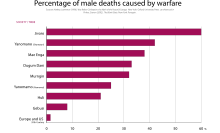

Wars grab headlines, but the individual risk of dying violently in an armed conflict is today relatively low—much lower than the risk of violent death in many countries that are not suffering from an armed conflict. For example, between 1976 and 2008, African Americans were victims of 329,825 homicides.[155][156] Although there is a widespread perception that war is the most dangerous form of armed violence in the world, the average person living in a conflict-affected country had a risk of dying violently in the conflict of about 2.0 per 100,000 population between 2004 and 2007. This can be compared to the average world homicide rate of 7.6 per 100,000 people. This illustration highlights the value of accounting for all forms of armed violence rather than an exclusive focus on conflict related violence. Certainly, there are huge variations in the risk of dying from armed conflict at the national and subnational level, and the risk of dying violently in a conflict in specific countries remains extremely high. In Iraq, for example, the direct conflict death rate for 2004–07 was 65 per 100,000 people per year and, in Somalia, 24 per 100,000 people. This rate even reached peaks of 91 per 100,000 in Iraq in 2006 and 74 per 100,000 in Somalia in 2007.[157]

History

Scientific evidence for warfare has come from settled, sedentary communities.[158] Some studies argue humans have a predisposition for violence (chimpanzees, also great apes, have been known to kill members of competing groups for resources like food).[159] A comparison across mammal species found that humans have a paleolithic adult homicide rate of about 2%. This would be lower than some other animals, but still high.[160] However, this study took into account the infanticide rate by some other animals such as meerkats, but not of humans, where estimates of children killed by infanticide in the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras vary from 15 to 50 percent.[161] Other evidence suggests that organized, large-scale, militaristic, or regular human-on-human violence was absent for the vast majority of the human timeline,[162][163][164] and is first documented to have started only relatively recently in the Holocene, an epoch that began about 11,700 years ago, probably with the advent of higher population densities due to sedentism.[163] Social anthropologist Douglas P. Fry writes that scholars are divided on the origins of possible increase of violence—in other words, war-like behavior:

There are basically two schools of thought on this issue. One holds that warfare... goes back at least to the time of the first thoroughly modern humans and even before then to the primate ancestors of the hominid lineage. The second positions on the origins of warfare sees war as much less common in the cultural and biological evolution of humans. Here, warfare is a latecomer on the cultural horizon, only arising in very specific material circumstances and being quite rare in human history until the development of agriculture in the past 10,000 years.[165]

Jared Diamond in his books Guns, Germs and Steel and The Third Chimpanzee posits that the rise of large-scale warfare is the result of advances in technology and city-states. For instance, the rise of agriculture provided a significant increase in the number of individuals that a region could sustain over hunter-gatherer societies, allowing for development of specialized classes such as soldiers, or weapons manufacturers.

In academia, the idea of the peaceful pre-history and non-violent tribal societies gained popularity with the post-colonial perspective. The trend, starting in archaeology and spreading to anthropology reached its height in the late half of the 20th century.[166] However, some newer research in archaeology and bioarchaeology may provide evidence that violence within and among groups is not a recent phenomenon.[167] According to the book "The Bioarchaeology of Violence" violence is a behavior that is found throughout human history.[168]

Lawrence H. Keeley at the University of Illinois writes in War Before Civilization that 87% of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and that 65% of them were fighting continuously. He writes that the attrition rate of numerous close-quarter clashes, which characterize endemic warfare, produces casualty rates of up to 60%, compared to 1% of the combatants as is typical in modern warfare. "Primitive Warfare" of these small groups or tribes was driven by the basic need for sustenance and violent competition.[169]

Fry explores Keeley's argument in depth and counters that such sources erroneously focus on the ethnography of hunters and gatherers in the present, whose culture and values have been infiltrated externally by modern civilization, rather than the actual archaeological record spanning some two million years of human existence. Fry determines that all present ethnographically studied tribal societies, "by the very fact of having been described and published by anthropologists, have been irrevocably impacted by history and modern colonial nation states" and that "many have been affected by state societies for at least 5000 years."[170]

The relatively peaceful period since World War II is known as the Long Peace.

The Better Angels of Our Nature

Steven Pinker's 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, argued that modern society is less violent than in periods of the past, whether on the short scale of decades or long scale of centuries or millennia. He argues for a paleolithic homicide rate of 15%.

Steven Pinker argues that by every possible measure, every type of violence has drastically decreased since ancient and medieval times. A few centuries ago, for example, genocide was a standard practice in all kinds of warfare and was so common that historians did not even bother to mention it. Cannibalism and slavery have been greatly reduced in the last thousand years, and capital punishment is now banned in many countries. According to Pinker, rape, murder, warfare and animal cruelty have all seen drastic declines in the 20th century.[171] Pinker's analyses have also been criticized, concerning the statistical question of how to measure violence and whether it is in fact declining.[172][173][174]

Pinker's observation of the decline in interpersonal violence echoes the work of Norbert Elias, who attributes the decline to a "civilizing process", in which the state's monopolization of violence, the maintenance of socioeconomic interdependencies or "figurations", and the maintenance of behavioural codes in culture all contribute to the development of individual sensibilities, which increase the repugnance of individuals towards violent acts.[175] According to a 2010 study, non-lethal violence, such as assaults or bullying appear to be declining as well.[176]

Some scholars disagree with the argument that all violence is decreasing arguing that not all types of violent behaviour are lower now than in the past. They suggest that research typically focuses on lethal violence, often looks at homicide rates of death due to warfare, but ignore the less obvious forms of violence.[177]

Society and culture

Beyond deaths and injuries, highly prevalent forms of violence (such as child maltreatment and intimate partner violence) have serious lifelong non-injury health consequences. Victims may engage in high-risk behaviours such as alcohol and substance misuse and smoking, which in turn can contribute to cardiovascular disorders, cancers, depression, diabetes and HIV/AIDS, resulting in premature death.[178] The balances of prevention, mitigation, mediation and exacerbation are complex, and vary with the underpinnings of violence.

Economic effects

In countries with high levels of violence, economic growth can be slowed down, personal and collective security eroded, and social development impeded. Families edging out of poverty and investing in schooling their sons and daughters can be ruined through the violent death or severe disability of the main breadwinner. Communities can be caught in poverty traps where pervasive violence and deprivation form a vicious circle that stifles economic growth. For societies, meeting the direct costs of health, criminal justice, and social welfare responses to violence diverts many billions of dollars from more constructive societal spending. The much larger indirect costs of violence due to lost productivity and lost investment in education work together to slow economic development, increase socioeconomic inequality, and erode human and social capital.

Additionally, communities with high level of violence do not provide the level of stability and predictability vital for a prospering business economy. Individuals will be less likely to invest money and effort towards growth in such unstable and violent conditions. One of the possible proves might be the study of Baten and Gust that used "regicide" as measurement unit to approximate the influence of interpersonal violence and depict the influence of high interpersonal violence on economic development and level of investments. The results of the research prove the correlation of the human capital and the interpersonal violence.[179]

In 2016, the Institute for Economics and Peace, released the Economic Value of Peace Archived 2017-11-15 at the Wayback Machine report, which estimates the economic impact of violence and conflict on the global economy, the total economic impact of violence on the world economy in 2015 was estimated to be $13.6 trillion[180] in purchasing power parity terms.

Religion and politics

Religious and political ideologies have been the cause of interpersonal violence throughout history.[181] Ideologues often falsely accuse others of violence, such as the ancient blood libel against Jews, the medieval accusations of casting witchcraft spells against women, and modern accusations of satanic ritual abuse against day care center owners and others.[182]

Both supporters and opponents of the 21st-century War on terrorism regard it largely as an ideological and religious war.[183][pages needed][184][pages needed][185][pages needed][186][pages needed] In 2007, US politician John Edwards said "the War on Terror was nothing more than a "slogan" and "a bumper sticker.""[187] In 1992, former research fellow with the US Cato Institute, Leon Hadar, considered that it wasn't "in America's interest to launch a crusade for democracy, neither is it in her interest to be perceived as the guarantor of the status quo and the major obstacle to reform".[188]

Vittorio Bufacchi describes two different modern concepts of violence, one the "minimalist conception" of violence as an intentional act of excessive or destructive force, the other the "comprehensive conception" which includes violations of rights, including a long list of human needs.[189]

Anti-capitalists say that capitalism is violent, that private property and profit survive only because police violence defends them, and that capitalist economies need war to expand.[190] In this view, capitalism results in a form of structural violence that stems from inequality, environmental damage, and the exploitation of women and people of colour.[191][192]

Frantz Fanon critiqued the violence of colonialism and wrote about the counter violence of the "colonized victims."[193][194][195]

Throughout history, most religions and individuals like Mahatma Gandhi have preached that humans are capable of eliminating individual violence and organizing societies through purely nonviolent means. Gandhi himself once wrote: "A society organized and run on the basis of complete non-violence would be the purest anarchy."[196] Modern political ideologies which espouse similar views include pacifist varieties of voluntarism, mutualism, anarchism and libertarianism.

Luther Seminary Old Testament scholar Terence E. Fretheim wrote about the Old Testament:

For many people, ... only physical violence truly qualifies as violence. But, certainly, violence is more than killing people, unless one includes all those words and actions that kill people slowly. The effect of limitation to a "killing fields" perspective is the widespread neglect of many other forms of violence. We must insist that violence also refers to that which is psychologically destructive, that which demeans, damages, or depersonalizes others. In view of these considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive, public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures, or kills. Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes, churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the blood. Moreover, many forms of systemic violence often slip past our attention because they are so much a part of the infrastructure of life (e.g., racism, sexism, ageism).[197]

See also

- Aestheticization of violence

- Aggression

- Ahimsa

- Alternatives to Violence Project

- Communal violence

- Corporal punishment

- De-escalation

- Domestic violence

- Fight-or-flight response

- Harm principle

- Hunting

- Legislative violence

- Non Violent Resistance (psychological intervention)

- Nonviolence

- Nonviolent Communication

- Nonviolent resistance

- Nonviolent revolution

- Pacifism

- Parasitism

- Predation

- Religious violence

- Resentment

- Sectarian violence

- Turning the other cheek

- Violence begets violence

- War

Notes

- ^ 'any interpretation of reality is always a form of violence in the sense that knowledge "can only be a violation of the things to be known" ... Several philosophers following Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, and Derrida have emphasized and explicated this fundamental violence.'[58]

- ^ "While the ontological violence of language does, in significant ways, sustain, enable, and encourage physical violence, it is a serious mistake to conflate them. [...] Violence is understood to be ineliminable in the first sense, and this leads to its being treated as a fundamental in the second sense, too.""[58]: 36

- ^ "Epistemic violence in testimony is a refusal, intentional or unintentional, of an audience to communicatively reciprocate a linguistic exchange owing to pernicious ignorance"[59]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Krug, Etienne G.; Dahlberg, Linda L.; Mercy, James A.; Zwi, Anthony B.; Lozano, Rafael (3 October 2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization (published 2002). p. 360. hdl:10665/42495. ISBN 92-4-154561-5.

- ^ WHO / Liverpool JMU Centre for Public Health, "Violence Prevention: The evidence" Archived 2012-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-15. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c Global status report on violence prevention 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization (published 2014). 9 January 2014. p. 274. hdl:10665/145086. ISBN 9789241564793.

- ^ Balcells, Laia; Stanton, Jessica A. (11 May 2021). "Violence Against Civilians During Armed Conflict: Moving Beyond the Macro- and Micro-Level Divide". Annual Review of Political Science. 24 (1): 45–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102229.

- ^ "Country Reports on Terrorism 2019". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ Nixon, Rob (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06119-4. OCLC 754842110.

- ^ Šmihula, Daniel (2013): The Use of Force in International Relations, p. 64, ISBN 978-8022413411.

- ^ Šmihula, Daniel (2013): The Use of Force in International Relations, p. 84, ISBN 978-8022413411.

- ^ Schechter DS, Willheim E, McCaw J, Turner JB, Myers MM, Zeanah CH (2011). "The relationship of violent fathers, posttraumatically stressed mothers, and symptomatic children in a preschool-age inner-city pediatrics clinic sample". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 26 (18): 3699–3719. doi:10.1177/0886260511403747. PMID 22170456. S2CID 206562093.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Violence against children". World Health Organization. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Injuries and violence". World Health Organization. 19 June 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.