User:LockeShocke/Why did Socialism fail in early 20th century America

by Ryan Jenkins

Early American Socialism and its Leaders

The common perception of America’s destiny being decided by only Democrats and Republicans is essentially only valid for the last 75 years. From the earliest disputes over rebellion from Britain, to the interpretation of the Constitution–through Whigs, Federalists, Bull Mooses and Reformers–America has seen a great number of political parties come and go. One notable “third party” to reach prominence around the turn of the 20th century was the Socialist Party. Influenced by revolutionary European thinking and gaining momentum from distraught workers and oppressed minorities, the Socialist party managed to successfully run hundreds of candidates for various positions around the nation. But, soon after it arose in 1876 as an official party, it became impotent and disappeared from the public eye. Where did the Socialist party go? Why did the movement collapse? Why did Socialism fail in early 20th century America?

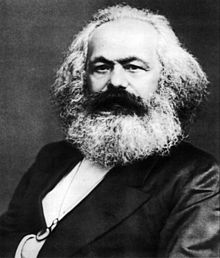

To understand Socialism’s demise, an understanding of its origins is necessary. The Socialist Party was officially founded in 1876 at a convention in Newark, New Jersey (Socialist Party of America on Wikipedia, 2005). The party was made up overwhelmingly1 of German immigrants, who had brought Marxist ideals with them to North America.

American Socialism was based on Marxist theology today known as “Democratic Socialism.” As a movement, the eventual goal was to give control of major industries to their respective employees, relinquishing “capital to those who create it,” as well as establish a welfare state, universal suffrage, and politically empower the [oppressed] working class, or “proletariat.”

The Socialist Party’s early approach to politics was similar to that of a reformist politician named Ferdinand Lassalle. He traveled Germany giving speeches, writing pamphlets, and negotiating with Chancellor Bismarck’s government in the mid-1800s. But, both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels disagreed with Lassalle’s stance on several issues, and they claimed that he was not “a true Communist:” they opposed reformist politics in favor of revolutionary tactics. Because the majority of Socialists in America were German Marxists, this also made Lassalle unpopular in the States (Ferdinand Lassalle on Wikipedia, 2005).

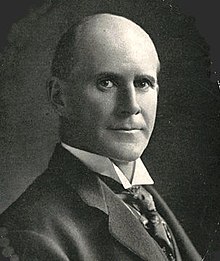

Bringing to light the resemblance of the American party’s politics to those of Lassalle, Daniel De Leon emerged as an early leader of the Socialist party. He was also an adamant supporter of unions, but critical of the collective bargaining movement within America at the time, favoring a slightly different approach2. The resulting disagreement between De Leon’s supporters and detractors within the party led to an early schism. “De Leon's opponents, led by Morris Hillquit, left the Socialist Labor Party in 1901 and fused with Eugene V. Debs' Social Democratic Party and formed the Socialist Party of America” (Socialist Labor Party of America on Wikipedia, 2005).

Before the communication revolutions of television and radio, the most famous figures were those who could sway a crowd with the power of a great speech. Eugene V. Debs, as the new leader of the Socialist movement, quickly gained national recognition as a charismatic orator. He was often inflammatory and controversial, but also strikingly modest and inspiring. He once said, “I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else… You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition” (Eugene V. Debs on Wikipedia, 2005). Debs lent a great and powerful air to the revolution with his speaking. “There was almost a religious fervor to the movement, as in the eloquence of Debs” (Zinn, 1980, p. 333).

The Socialist movement became coherent and energized under Debs. It included “scores of former Populists, militant miners, and blacklisted railroad workers, who were… inspired by occasional visits from national figures like Eugene V. Debs” (Zinn, 1980, p. 332).

Socialism's ties to Labor

The Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations, because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution–or so they thought–in a technique known as collective bargaining. By banding together into “unions” and refusing to work, or “striking,” workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing management to meet their demands. From Daniel De Leon’s early proposal to organize unions with a Socialist purpose, the two movements became closely tied. One major ideal they had in common was the spirit of collectivism: both in the Socialist platform and in the idea of collective bargaining.

The most prominent unions of the time were the American Federation of Labor, the Knights of Labor, and the Industrial Workers of the World. Uriah S. Stephens founded the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor around secrecy and a semireligious aura to “create a sense of solidarity” (Tindall et al, 1984, p. 827). The Knights was, in essence, “one big union of all workers” (Tindall et al, 1984, p. 828). In 1886, a convention of delegates from twenty separate unions formed the American Federation of Labor, with Samuel Gompers as its head. It peaked at 4 million members. The Industrial Workers of the World (or “Wobblies”) was formed along the same lines as the Knights, to become one big union. The IWW found early supporters in De Leon and Debs.

The Socialist movement was able to gain strength from its ties to labor. “The [economic] panic of 1907, as well as the growing strength of the Socialists, Wobblies, and trade unions, speeded the process of reform” (Zinn, 1980, p. 342). However, corporations sought to protect their profits, and took steps against unions and strikers. They hired strikebreakers and pressured the government to call in the national militia when workers refused to do their jobs. A number of strikes dissolved into violent confrontations.

In May of 1884, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the Haymarket Square in Chicago, demanding an eight-hour day in all trades. When police arrived, an unknown person threw a bomb into the crowd, killing one person and injuring several others. “In a trial marked by prejudice and hysteria,” seven anarchists, six of them German speaking, were sentenced to death with no evidence linking them to the bomb (Tindall and Shi, 1984, p. 829).

In early 1894, a dispute broke out between George Pullman and his employees. Debs, then-leader of the American Railway Union, organized a strike. United States Attorney General Olney and President Cleveland took the matter to court and were granted several injunctions preventing railroad workers from “interfering with interstate commerce and the mails” (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 29). The judiciary of the time denied the legitimacy of strikers. Said one judge, “[neither] the weapon of the insurrectionist, nor the inflamed tongue of him who incites fire and sword is the instrument to bring about reforms” (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 29). This was the first sign of a clash between the government and Socialist ideals.

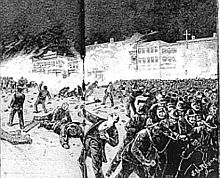

In 1914, one of the worst labor conflicts in American history took place at a mining colony in Colorado called Ludlow. After workers struck with grievances ranging from requests for an eight-hour day to allegations of subjugation, the National Guard was called in by Colorado governor Elias Ammons. That winter, Guardsmen made 172 arrests3 (Kick et al, 2002, p. 263).

The strikers began to fight back, killing four mine guards and firing into a separate camp where strikebreakers lived. When body of a strikebreaker was found nearby, the National Guard’s General Chase ordered the tent colony destroyed in retaliation (Kick et al, 2002, p. 263).

“On Monday morning, April 20, two dynamite bombs were exploded, in the hills above Ludlow... a signal for operations to begin. At 9 AM a machine gun began firing into the tents [where strikers were living], and then others joined” (Kick et al, 2002, p. 263). One eyewitness reported, “The soldiers and mine guards tried to kill everybody; anything they saw move” (Kick et al, 2002, p. 263). That night, the National Guard rode down from the hills surrounding Ludlow and set fire to the tents. Twenty-six people, including two women and eleven children, were killed (Kick et al, 2002, p. 264).

Union members now feared for their lives when striking. The military, which saw strikers as dangerous insurgents, intimidated and threatened them. This compounded with a public backlash against anarchists and radicals. As public opinion of strikes and unions was soured, the Socialists often appeared guilty by association. They were lumped together with strikers and anarchists under a blanket of public distrust.

Political Oppression

Aside from military, the Socialists would meet harsh political opposition as well when exercising their First Amendment right. On April 7th, 1917, the day after the United States entered World War I, an emergency convention of the Socialist party was held in St. Louis. They declared the war “a crime against the people of the United States” (Zinn, 1980, p. 355) and began holding anti-war rallies. Socialist anti-draft demonstrations drew as many as 20,000 (Zinn, 1980, p. 356).

In June of 1917, Wilson signed into law the Espionage Act4, which included a clause providing prison sentences for up to twenty years for “Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty… or willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment of service of the United States” (Zinn, 1980, p. 356). The Socialists, with their talk of draft dodging and war-opposition, suddenly found themselves the target of persecution. Scores were convicted of treason and jailed.

After visiting three Socialists imprisoned in Canton, Ohio, Eugene V. Debs crossed the street and made a two-hour speech to a crowd in which he condemned the war and big business. “Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder… The master class has always declared the war and the subject class has always fought the battles,” Debs told the crowd (Zinn, 1980, 358).

He was immediately arrested and soon convicted under the Espionage Act. During his trial, he did not take the stand, nor call a witness in his defense. However, before the trial began, and after his sentencing, he made speeches to the jury: “I have been accused of obstructing the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war… I have sympathy with the suffering, struggling people everywhere…” He also uttered the words he would become most famous for: “While there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free” (Eugene V. Debs on Wikipedia, 2005). Debs was sentenced to ten years in prison5, stripped of his citizenship, and disenfranchised for life.

During the war, the Socialists were wracked by assaults on their right to free speech. “The patriotic fervor of war [was] invoked. The courts and jails [were] used to reinforce the idea that certain ideas, certain kinds of resistance, could not be tolerated” (Zinn, 1980, p. 367).

The government crackdown on dissenting radicalism paralleled public outrage towards opponents of the war. Several groups were formed on the local and national levels to silence dissent. The American Vigilante Patrol, a subdivision of the American Defense Society, was formed with the purpose “to put an end to seditious street oratory” (Zinn, 1980, p. 360). The Department of Justice sponsored an organization known as the American Protective League, which kept track of cases of “disloyalty.” It eventually claimed it had found 3,000,000 such cases (Zinn, 1980, p. 360). “Even if these figures are exaggerated, the very size and scope of the League gives a clue to the amount of ‘disloyalty’” (Zinn, 1980, p. 360).

The press was also instrumental in spreading feelings of hatred against dissenters:

- In April of 1917, the New York Times quoted [former Secretary of War] Elihu Root as saying: ‘We must have no criticism now.’ A few months later it quoted him again that ‘there are men walking about the streets of this city tonight who ought to be taken out at sunrise tomorrow and shot for treason’… The Minneapolis Journal carried an appeal by the [Minnesota Commission of Public Safety] ‘for all patriots to join in the suppression of anti-draft and seditious acts and sentiment’ (Zinn, 1980, p. 360).

Two steps back, one forward

Meanwhile, corporations pressured the government to deal with strikes and other disruptions from disgruntled workers. The government felt especially pressured to keep war-related industries running. “As worker discontent and strikes… intensified in the summer of 1917, demands grew for prompt federal action… The anti-labor forces concentrated their venom on the IWW” (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 67). Soon, “the halls of Congress rang with denunciations of the IWW” and the government sided with industry; “federal attorneys viewed strikes not as the behavior of discontented workers but as the outcome of subversive and even German influences” (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 67).

On September 5th, 1917, at the request of President Wilson, the Justice Department conducted a raid on the Industrial Workers of the World. They stormed every one of the 48 IWW headquarters in the country. “By month’s end, a federal grand jury had indicted nearly two hundred IWW leaders on charges of sedition and espionage” under the Espionage Act (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 69). Their sentences ranged from a few months to ten years in prison. An ally of the Socialist party had been practically destroyed.

However, Wilson did recognize a problem with the state of labor in America. In 1918, he created the National War Labor Board in an attempt to reform labor practices. The Board included an equal number of members from labor and business, and members of the AFL. The Board was able to “institute the eight-hour day in many industries… to raise wages for transit workers… [and] to demand equal pay for women…” (Dubofsky, 1994, p. 73). It also required employers to bargain collectively, effectively making unions legal. The Socialist movement, for the first time, saw justice being done in the mitigation of the plight of the worker.

Internal strife and public prejudice

But the next year, internal strife would cause a schism. After Vladimir Lenin’s successful revolution in Russia, he invited the Socialist Party to join the Communist Third International6. The debate over whether to align with Lenin caused a major rift in the party. A referendum to join Lenin’s “Comintern” passed with 90% approval, but the moderates who were in charge of the Party expelled the extreme leftists before this could take place. The expelled members formed the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party of America. The Socialist Party remained, with only a handful of moderates left, at one third of its original size (Socialist Party of America on Wikipedia, 2005).

In addition, a wave of prejudice swept the country after the war. The nation indulged in anti-immigrant and anti-Communist sentiment. “After the Russian Revolution of 1917, America’s ruling class became almost obsessed with Communism” (Axelrod and Philips, 1992, p. 254). This was known as the first Red Scare7. Anarchists had sent a number of mail-bombs to prominent businessmen and government leaders. However, “Little distinction was made between working-class Communists and the suspected anarchists” (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 254).

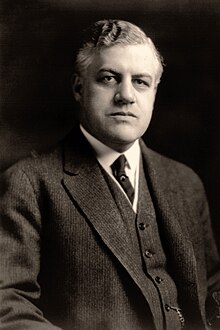

Attorney General Palmer, after he himself received a bomb in the mail, set out to stop the “Communist conspiracy” that he believed was operating inside the United States. “Foreigners and labor unions were his prime targets” (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 256). He created a secret organization, the General Intelligence Division, led by J. Edgar Hoover8. Hoover soon amassed a card-catalogue system with information on 150,000 individuals and 60,000 groups and publications (Axlerod et al, 1992, p. 256). Palmer and Hoover both published press releases and circulated anti-Communist propaganda.

Then, on January 2nd, 1920, the “Palmer Raids” began.

- In Manhattan, the target was the Russian People’s House, where 183 men were initially arrested… The arrests were particularly brutal. Some people were hurled down the stairs of the Russian People’s House. Others were beaten. Drunk with the success of the raid, Palmer went to Congress a week later to ask that a peacetime sedition act be passed... [Congress] cheered Palmer in the halls of the Capitol (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 256).

On that single day in 1920, Palmer’s agents rounded up 6,000 people (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 256). In the subsequent trials, the Labor Department ruled that mere “membership in a Communist organization was sufficient ground for the deportation of aliens” (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 256). However, it later ruled that the incarcerations and deportations were illegal9, halting Palmer’s reign of terror.

The Red Scare was over, but Americans’ xenophobia remained.

- Americans feared that the millions of new immigrants would take jobs from the native-born. America’s capitalists had long been blaming the labor unrest of previous decades on radical dissidents among the immigrants… Americans seemed willing to transform their war-time fear of Germans to a post-war fear of the... immigrant industrial worker (Axelrod et al, 1992, pg. 265).

Congress soon passed the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, heavily restricting immigration from [typically Communist] eastern and southern Europe.

The end of popular Socialism

“When the twenties began… the IWW was destroyed, the Socialist party falling apart. The strikes were beaten down by force, and the economy was doing just well enough for just enough people to prevent mass rebellion” (Zinn, 1980, p. 373). Thus the fall of the Socialist movement was the result of a number of constrictions and attacks from several directions:

The Socialists had lost a major ally in the Wobblies, and their free speech had been restricted, if not denied. Immigrants, a major base of the Socialist movement, were discriminated against and looked down upon. Eugene V. Debs–the once charismatic leader of the Socialists–was in prison, along with hundreds of fellow dissenters. Wilson’s National War Labor Board and a number of legislative acts10 had ameliorated the plight of the workers. Now, the Socialists were regarded as being unnecessary, the “lunatic fringe,” and a group of subversive, untrustworthy immigrant radicals. They were painted as violent dissidents and feared. The public, the courts, and Congress exhibited prejudice against them. After crippling schisms within the party and a change in public opinion due to the Palmer Raids and the press, the Socialist party found itself unable to gather popular support.

...

The Party would reach its peak in 1912. At one time, it boasted 33 city mayors and several seats in state legislatures (Tindall et al, 1984, p. 838). When running for President in 1912, Eugene V. Debs won 6% of the popular vote (U.S. presidential election (1912) on Wikipedia, 2005). But, in the past 92 years, the party has not even mustered 4%11.

The Socialist movement, born out of the strife of the laboring class, has eventually faded into obscurity and, like so many other parties, it was little more than a flash in the political pan.

Appendix

- This Eastern European country influenced the party so heavily that its official language was German for its first three years in existence.

- The difference between De Leon’s ideal union situation and the one being practiced at the time is minute and necessitates a comparison between Anarcho-Syndicalism and DeLeonism. This complex economic discussion is outside the scope of this paper.

- As the conflict dragged on, the state of Colorado was unable to pay the salaries of many National Guardsmen. As enlisted men dropped out, mine guards took their places, their uniforms, an their weapons.

- This Act is still on the books today and has been repeatedly used in peacetime. Officially, since the Korean War in the 1950s, the United States has been in a constant “state of emergency” (Zinn, 1980, p. 356).

- Debs served 32 months of his sentence until President Warren G. Harding pardoned him.

- Lenin founded the Communist International (or Comintern) after the Bolshevik revolution as an international organization working together towards the eventual “complete abolition of the state” (Comintern on Wikipedia, 2005).

- This is also known as the “Palmer Raids.” Senator Joseph McCarthy, directly following the Second World War, orchestrated the second, more famous Red Scare. It found the same targets in Communists and foreigners.

- At this time, J. Edgar Hoover was working as Palmer’s special assistant in the Justice Department.

- “Since the Communist Labor Party accepted the possibility of change through Parliamentary action, it could not be considered an advocate of violent revolution” (Axelrod et al, 1992, p. 256).

- By the turn of the century, the states had passed over 1,600 acts relating to working conditions (Tindall et al, 1984, p. 888).

- Socialists in the United States recently celebrated 10,303 popular votes, .009%, for Walter F. Brown in the 2004 Presidential election (compared to Debs’ 900,369 in 1912).

References

Axelrod, Alan and Philips, Charles. (1992). What every American should know about American history.

(Reprinted ed.) Rob Adams Inc. Publishers.

Dubofsky, Melvyn. (1994). The state and labor in modern America.

University of North Carolina Press.

Eugene V. Debs. (March 17, 2005). Wikipedia.

Retrieved on March 21, 2005 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugene_V._Debs

Ferdinand Lassalle. (March 4, 2005). Wikipedia.

Retrieved on March 21, 2005 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Lassalle

Kick, Russ (editor). (2002). Everything you know is wrong.

New York: The Disinformation Company.

Socialist Party of America. (March 10, 2005). Wikipedia.

Retrieved March 20, 2005 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialist_Party_of_America

Tindall, George Brown and Shi, David E. (1984). America: a narrative history.

(Full sixth ed., one vol.). W. W. Norton and Company.

U.S. presidential election (1912). (March 21, 2005). Wikipedia.

Retrieved on March 22, 2005 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._presidential_election%2C_1912

Zinn, Howard. (1980). A people's history of the United States 1492-present.

New York: HarperCollins.