User:Joopercoopers/Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal

| Article |

|

Timeline |

|

Statistics |

|

Gallery |

|

Maps |

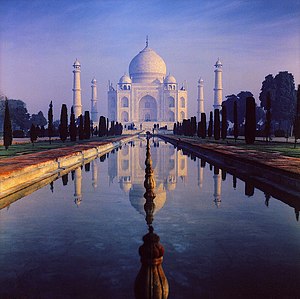

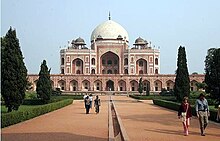

This is a test page to be used as a working example - please contribute to discussion at User:Joopercoopers/Tabbed articles  The Taj Mahal represents the finest and most sophisticated example of Mughal architecture. Its origins lie in the moving circumstances of its commission and the culture and history of the Islamic Mughal empire's rule of large parts of India. The mausoleum was commissioned by the distraught Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan upon the death of his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Today it is one of the most famous and recognisable buildings in the world and while the white domed marble mausoleum is the most familiar part of the monument, the Taj Mahal is an extensive complex of buildings and gardens that extends over 22.44 Hectares[a] and includes subsidiary tombs, waterworks infrastructure, the small town of 'Taj Ganji' and a 'moonlight garden' to the north of the river. Construction began in 1632 CE, (1041 AH), on the south bank of the River Yamuna in Agra, India and was completed in 1648 CE (1058 AH). The design was conceived as both an earthly replica of the house of Mumtaz in paradise and an instrument of propaganda for the emperor. Who designed the Taj Mahal is unclear; although it is known that a large team of designers and craftsmen were responsible with Jahan himself taking an active role. Ustad Ahmad Lahauri is considered the most likely candidate as the principal designer.[1] Precedents The erection of Mughal tombs to honour the dead is the subject of a theological dialogue exemplified by the varied ways in which they built funerary monuments. Orthodox Islam found tombs problematic because a number of Hadith forbade the construction of tombs as irreligious. As a culture attempting to accommodate the local Hindu populace, opposition also came from their tradition which held dead bodies as impure, and by extension, the structures over them similarly impure. However for a majority of Muslims, the spiritual power (barakat) of visiting the resting places (ziyarat) of those venerated in Islam was a force by which greater personal sanctity could be achieved. So frequently for Muslims, tombs could be considered legitimate providing they did not strive for pomp and were seen as a means to provide a reflection of paradise (Jannah) here on earth. The ebb and flow of this debate can be seen in the Mughul's dynastic mausoleums beginning with the Tomb of Timur in Samarkand. Here Timur is buried under a fluted dome and a traditional Persian Iwan is employed as an entrance. The Tomb of Babur in Kabul is a much more modest affair where a simple cenotaph, exposed to the sky, is laid out in the centre of a walled garden.[2]  Humayun's tomb is seen as one of the most direct influences on the Taj Mahal's design and was a direct response to the Tomb of Timur, featuring a central dome of white marble, red sandstone facings, a plinth, geometric symmetrical planning, chatris, iwans and a charbagh. Designed by Humayun's son Akbar it set the precedent for Mughal emperor's children constructing the mausoleums of their fathers.[3]  The Tomb of Jahangir at Shahdara (Lahore), begun in 1628 CE (1037 AH), only 4 years before the construction of the Taj and again without a dome, takes the form of a simple plinth with a minaret at each corner.[2]

The concept of the paradise garden was one the Mughals brought from Persian Timurid gardens. It was the first architectural expression they made in the Indian sub-continent, fulfilling diverse functions with strong symbolic meanings. Known as the charbagh, in its ideal form it was laid out as a square subdivided into four equal parts. The symbolism of the garden and its divisions are noted in mystic Islamic texts which describe paradise as a garden filled with abundant trees flowers and plants. Water also plays a key role in these descriptions: In Paradise four rivers source at a central spring or mountain, and separate the garden by flowing towards the cardinal points. They represent the promised rivers of water, milk, wine and honey.[4] The centre of the garden, at the intersection of the divisions is highly symbolically charged and is where, in the ideal form, a pavilion, pool or tomb would be situated. The tombs of Humayun, Akbar and Jahangir, the previous Mughal emperors, follow this pattern. The cross axial garden also finds independent precedents within South Asia dating from the 5th century with the royal gardens of Sigiriya in Sri Lanka which were laid out in a similar way.[5] For the tomb of Jahan's late wife though, where the mausoleum is sited at the edge of the garden, a variant of the charbagh is suggested by Ebba Koch; that of the waterfront garden. Developed by the Mughuls for the specific conditions of the Indian plains where slow flowing rivers provide the water source, the water is raised from the river by animal driven devices known as purs and stored in cisterns. A linear terrace is set close to the riverbank with low-level rooms set below the main building opening on to the river. Both ends of the terrace were emphasised with towers. This form was brought to Agra by Babur and by the time of Shah Jahan, gardens of this type as well as the more traditional charbagh lined both sides of the Jumna river. The riverside terrace was designed to enhance the views of Agra for the imperial elite who would travel in and around the city by river. Other scholars suggest another explanation for the eccentric siting of the mausoleum at the Taj Mahal complex. If the Midnight Garden to the north of the river Jumna is considered an integral part of the complex, then the mausoleum can be interpreted as being in the centre of a garden divided by a real river and thus is more in the tradition of the pure charbagh.[6][7]

The favourite form for both Mughal garden pavilions and mausolea (seen as a funerary form of pavilion) was the hasht bihisht which translates from Persian as 'eight paradises'. These were square or rectangular planned buildings divided into nine sections such that a central domed chamber is surrounded by eight elements. Later developments of the hasht bihisht divided the square at 45 degree angles to create a more radial plan which often also includes chamfered corners; examples of which can be found in Todar Mal's Baradari at Fatehpur Sikri and Humayun's Tomb. Each element of the plan is reflected in the elevations with iwans with the corner rooms finding expression through smaller arched niches. Often such structures are topped with chattris, small pillared pavilions at each corner. The eight divisions and frequent octagonal forms of such structures represent the eight levels of paradise for Muslims. The paradigm was not confined solely to Islamic antecedents. The Chinese magic square was employed for numerous purposes including crop rotation and also finds a Muslim expression in the wafq of their mathematicians. Ninefold schemes find particular resonance in the Indian mandalas, the cosmic maps of Hinduism and Buddhism.[8] In addition to Humayun's tomb, the more closely contemporary Tomb of Itmad-Ud-Daulah provided many influences on the Taj Mahal and marked a new era of Mughal architecture. It was built by the empress Nur Jehan for her father from 1622–1625 CE (1031–1034 AH). It is small in comparison to many other Mughal-era tombs, but so exquisite is the execution of its surface treatments, it has been described as a jewel box. The garden layout, hierarchal use of white marble and sandstone, Parchin kari inlay designs and latticework presage many elements of the Taj Mahal. It is also interesting to note that the cenotaph of Nur Jehan's father is laid, off centre, to the west of her mother. These close similarities with the tomb of Mumtaz have earned it the sobriquet - The Baby Taj.[9]

Minarets did not become a common feature of Mughal architecture until the 17th century, particularly under the patronage of Shah Jahan. A few precedents exist in the 20 years before the construction of the Taj in the Tomb of Akbar and the Tomb of Jahangir. Their increasing use was influenced by developments elsewhere in the Islamic world, particularly in Ottoman and Timurid architecture. This development has been seen as evidence of an increasing religious orthodoxy of the Mughal dynasty.[10]

Concepts, symbolism and interpretationsUnder the reign of Shah Jahan the symbolic content of mughal architecture reached its peak.[11] Inspired by a verse by Bibadal Khan[g], the imperial goldsmith and poet, and in common with most Mughal funerial architecture, the Taj Mahal complex was conceived as a replica on earth of the house of Mumtaz in paradise. This theme permeates the entire complex and informs the design of all its elements.[12] A number of secondary principles inform the design and appearance of the complex, of which hiearachy is the most dominant. A deliberate interplay was established between the building's elements, its surface decoration, materials, geometric planning and its acoustics. This interplay extends from what can be seen with the senses, into religious, intellectual, mathematical and poetic ideas.[12] The constantly changing sunlight that illuminates the building reflected from its translucent marble is not a happy accident, it had a metaphoric role associated with the presence of god.[13] Symmetry and geometric planning played an important role in ordering the complex and reflected a trend towards formal systematization that was apparent in all of the arts emanating from Jahan's imperial patronage. Bilateral symmetry expressed simultaneous ideas of pairing, counterparts and integration, reflecting intellectual and spiritual notions of universal harmony. A strict and complex set of implied grids based on the Mughul Gaz unit of measurement provided a flexible means of bringing proportional order to all the elements of the Taj Mahal.[14] Hierarchical ordering of architecture is used by most cultures to emphasise particular elements of a design and to create drama. In the Taj Mahal, the hierarchical use of red sandstone and white marble contributes manifold symbollic significance. The Mughals were elaborating on a concept which traced its roots to earlier Hindu practices, set out in the Vishnudharmottara Purana, which recommended white stone for buildings for the Brahmins (priestly caste) and red stone for members of the Kshatriyas (warrior caste). By building structures that employed such colour coding, the Mughals identified themselves with the two leading classes of Indian social structure and thus defined themselves as rulers in Indian terms. Red sandstone also had significance in the Persian origins of the Mughal empire where red was the exclusive colour of imperial tents. In the Taj Mahal the relative importance of each building in the complex is denoted by the amount of white marble (or sometimes white polished plaster) that is used.[12][15] The use of naturalist ornament demonstrates a similar hierarchy. Wholly absent from the Jilaukhana and caravanserai areas, it is used with increasing frequency as the processionary path approaches the mausoleum. Its symbolism is multifaceted, on the one hand evoking a more perfect, stylised and permanent garden of paradise than could be found growing in the earthly garden; on the other, an instrument of propaganda for Jahan's chroniclers who portrayed him as an 'erect cypress of the garden of the caliphate' and frequently used plant metaphors to praise his good governance, person, family and court. Plant metaphors also find a commonality with Hindu traditions where such symbols as the 'vase of plenty' (Kalasha) can be found and were borrowed by the mughal architects.[16] Sound was also used to express ideas of paradise. The interior of the mausoleum has a reverberation time (the time taken from when a noise is made until all of its echoes have died away) of 28 seconds providing an atmosphere where the words of the Hafiz, as they prayed for the soul of Mumtaz, would linger in the air.[17]

The popular view of the Taj as one of the world's monuments to a great "love story" is born out by the contemporary accounts and most scholars accept this has a strong basis in fact.[18][19] The building was also used to assert Jahani propaganda concerning the 'perfection' of the Mughal leadership. The extent to which the Taj uses propaganda is the subject of some debate amongst contemporary scholars. Wayne Begley put forward an interpretation in 1979 that exploits the Islamic idea that the 'Garden of paradise' is also the location of the 'throne of god' on the day of judgement. In his reading the Taj Mahal is seen as a monument where Shah Jahan has appropriated the authority of the 'throne of god' symbolism for the glorification of his own reign.[20] Koch disagrees, finding this an overly elaborate explanation and pointing out that the 'Throne' sura from the Qu'ran (sura2 verse 255) is missing from the calligraphic inscriptions.[21] This period of Mughal architecture best exemplifies the maturity of a style that had synthesised Islamic architecture with its indigenous counterparts. By the time the Mughals built the Taj, though proud of their Persian and Timurid roots, they had come to see themselves as Indian. Copplestone writes "Although it is certainly a native Indian production, its architectural success rests on its fundamentally Persian sense of intelligible and undisturbed proportions, applied to clean, uncomplicated surfaces."[3] Architects and craftsmenHistory obscures precisely who designed the Taj Mahal. In the Islamic world at the time, the credit for a building's design was usually given to its patron rather than its architects. From the evidence of contemporary sources, it is clear that a team of architects were responsible for the design and supervision of the works, but they are mentioned infrequently. Shah Jahan's court histories emphasise his personal involvement in the construction and it is true that, more than any other Mughal emperor, he showed the greatest interest in building, holding daily meetings with his architects and supervisors. The court chronicler Lahouri, writes that Jahan would make "appropriate alterations to whatever the skilful architects designed after many thoughts, and asked competent questions."[22] Two architects are mentioned by name, Ustad Ahmad Lahauri[1][23] and Mir Abd-ul Karim in writings by Lahauri's son Lutfullah Muhandis.[24] Ustad Ahmad Lahauri had laid the foundations of the Red Fort at Delhi. Mir Abd-ul Karim had been the favourite architect of the previous emperor Jahangir and is mentioned as a supervisor,[h] together with Makramat Khan,[24] of the construction of the Taj Mahal.[25] Similarly, the individual craftsmen are not named by the historical sources, but they were experts in their fields and were drawn from all over India. European chroniclers give unsubstantiated figures of as many as 20,000 men may have worked on the construction. Stonecutters and masons left their marks of various designs, including predominantly Hindu names with some Muslim, indicating the work force was drawn across religious creeds.[26] The exquisite and highly skilled parchin kari work was developed by Mughal lapidarists from techniques taught to them by Italian craftsmen employed at court. The look of European herbals, books illustrating botanical species, was adapted and refined in Mughal parchin kari work.[27] Site16th–17th Century AgraBabur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, created the first Mughal garden known as Ram Bagh in Agra in 1526CE. Thereafter, gardens became important Mughal symbols of power, changing the emphasis from pre-Mughal symbols such as forts. The shift can be explained in terms of the intoduction of a new ordered aesthetic, an artistic expression with religious and funery aspects and as a metaphor for Babur's ability to control the arid Indian planes and hence the country at large.[28] Babur rejected much of the indigenous and Lodhi built forms on the opposite bank and attempted to create new ones inspired by Persian gardens and royal encampments. Ram Bagh was followed by an extensive, regular and integrated complex of gardens and palaces stretching for more than a kilometer along the river. A high continuous stone plinth bounded the transition between gardens and river and established the framework for future development in the city.[29] In the following century, a thriving riverfront garden city developed on both sides of the Yamuna. Subsequent Mughal emperors developed both sides of the river including the rebuiding of Agra Fort, by Akbar, completed in 1573. By the time Jahan ascended to the throne, Agra's population had grown to approximately 700,000 and was, as Abdul Aziz writes, "a wonder of the age - as much a centre of the arteries of trade both by land and water as a meeting-place of saints, sages and scholars from all Asia.....a veritable lodestar for artistic workmanship, literary talent and spiritual worth".[30][31] Agra became a city centred on its waterfront and developed partly eastwards but mostly westwards from the rich estates that lined the banks. The prime sites remained those that had access to the river and the Taj Mahal was built in this context, but uniquely, on both sides of the river. Clickable mapClick map to navigate

Dimensional organisationThat the Taj comlex is ordered by grids is self evident from examination of any plan. However, it was not until 1989 that Begley and Desai attempted the first detailed scholastic examination of how the various elements of the Taj might fit into a coordinating grid. Numerous 17th century accounts detail the precise measurements of the complex in terms of the Gaz or zira, the Mughal linear yard, equivalent to approximately 80-92cm. Begley and Desai concluded a 400 gaz grid was used and then subdivided and that the various descrepancies they discovered were due to errors in the contemporary descriptions.[33][34] More recent research and measurement by Koch and Richard André Barraud suggests a more complex method of ordering that relates better to the 17th century records. Whereas Begley and Desai had used a simple fixed grid on which the buildings are superimposed, Koch and Barraud found the layout's proportions were better explained by the use of a generated grid system in which specific lengths may be divided in a number of ways such as halving, dividing by three or using decimal systems. They suggest the 374 gaz width of the complex given by the contemporary historians was correct and the Taj is planned as a tripartite rectangle of three 374 gaz squares. Different modular divisions are then used to proportion the rest of the complex. A 17 gaz module is used in the jilaukhana, bazaar and caravanserais areas whereas a more detailed 23 gaz module is used in the garden and terrace areas (since their width is 368 gaz, a multiple of 23). The buildings were in turn proportioned using yet smaller grids superimposed on the larger organisational ones. The smaller grids were also used to establish elevational proportion throughout the complex.[33] Such apparently peculiar numbers make more sense when seen as part of Mughal geometric understanding. Octagons and triangles, which feature extensively in the Taj, have particular properties in terms of the relationships of their sides. A right handed triangle with two sides of 12 will have a hypotenuse of 17, similarly if it has two sides of 17 it's hypotenuse will be 24. An octagon with a width of 17 will have sides of exactly 7, which is the basic grid upon which the mausoleum, mosque and Mihman Khana are planned.[33] Descrepancies remain in Koch and Barraud's work which they attribute to some figures being rounded fractions, innacuracies of reporting from third persons and errors in workmanship (most notable in the caravanserais areas further from the tomb itself).[33] Mausoleum (Rauza-i munauwara) The focus and climax of the Taj Mahal complex is the symmetrical white marble tomb; a cubic building with chamfered corners, with arched recesses known as pishtaqs. It is topped by a large dome and several pillared, roofed chhatris. In plan, it has a near perfect symmetry about 4 axes and is arranged in the 'hasht bihisht' form found in the tomb of Humayun. It comprises 4 floors; the lower basement storey containing the tombs of Jahan and Mumtaz, the entrance storey containing identical cenotaphs of the tombs below in a much more elaborate chamber, an ambulatory storey and a roof terrace.

The hierarchical ordering of the entire complex reaches its crescendo in the main chamber housing the cenotaphs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz. Mumtaz's cenotaph sits at the geometric centre of the building; Jahan was buried at a later date by her side to the west - an arrangement seen in other Mughal tombs of the period such as Itmad-Ud-Daulah.[35] Marble is used exclusively as the base material for increasingly dense, expensive and complex parchin kari floral decoration as one approaches the screen and cenotpahs which are inlaid with semi-precious stones. The use of such inlay work is often reserved in Shah Jahani architecture for spaces associated with the emperor or his immediate family. The ordering of this decoration simultaneously emphasises the cardinal points and the centre of the chamber with dissipating concentric octagons. Such hierarchies appear in both Muslim and Indian culture as important spiritual and atrological themes. The chamber is an abundant evocation of the garden of paradise with representations of flowers, plants and arabesques and the calligraphic inscriptions in both the thuluth and the less formal naskh script, [15] Muslim tradition forbids elaborate decoration of graves, so the bodies of Mumtaz and Shah Jahan are laid in a relatively plain chamber beneath the inner chamber of the Taj. They are buried on a north-south access, with faces turned right (west) toward Mecca. The Taj has been raised over their cenotaphs (from Greek keno taphas, empty tomb). The cenotaphs mirror precisely the placement of the two graves, and are exact duplicates of the grave stones in the basement below. Mumtaz's cenotaph is placed at the precise center of the inner chamber. On a rectangular marble base about 1.5 by 2.5 m is a smaller marble casket. Both base and casket are elaborately inlaid with precious and semiprecious gems. Calligraphic inscriptions on the casket identify and praise Mumtaz. On the lid of the casket is a raised rectangular lozenge meant to suggest a writing tablet.[citation needed] Shah Jahan's cenotaph is beside Mumtaz's to the western side. It is the only asymmetric element in the entire complex. His cenotaph is bigger than his wife's, but reflects the same elements: A larger casket on slightly taller base, again decorated with astonishing precision with lapidary and calligraphy which identifies Shah Jahan. On the lid of this casket is a sculpture of a a small pen box. (The pen box and writing tablet were traditional Mughal funerary icons decorating men's and women's caskets respectively.)[citation needed] An octagonal marble screen or jali borders the cenotaphs and is made from eight marble panels. Each panel has been carved through with intricate piercework. The remaining surfaces have been inlaid with semiprecious stones in extremely delicate detail, forming twining vines, fruits and flowers. The actual graves are a level below.

Riverfront terrace (Chameli Farsh)Plinth and terrace

At the corners of the plinth stand minarets — four large towers each more than 40 meters tall. The towers are designed as working minarets, a traditional element of mosques, a place for a muezzin to call the Islamic faithful to prayer. Each minaret is effectively divided into three equal parts by two working balconies that ring the tower. At the top of the tower is a final balcony surmounted by a chattri that mirrors the design of those on the tomb. Each of the minarets was constructed slightly out of plumb to the outside of the plinth, so that in the event of collapse (a typical occurrence with many such tall constructions of the period) the material would tend to fall away from the tomb.[citation needed] Jawab and Mosque  The mausoleum is flanked by two almost identical buildings on either side of the platform. To the west is the Mosque, to the east is Jawab. The Jawab, meaning 'answer' balances the bilateral symmetry of the composition and was originally used as a place for entertaining and accommodation for important visitors. It differs from the mosque in that it lacks a mihrab, a niche in a mosque's wall facing Mecca, and the floors have a geometric design, while the mosque floor was laid out with the outlines of 569 prayer rugs in black marble. The mosque's basic tripartite design is similar to others built by Shah Jahan, particularly the Masjid-i-Jahan Numa in Delhi — a long hall surmounted by three domes. Mughal mosques of this period divide the sanctuary hall into three areas: a main sanctuary with slightly smaller sanctuaries to either side. At the Taj Mahal, each sanctuary opens onto an enormous vaulting dome. Garden (Charbagh) The large charbagh (a formal Mughal garden divided into four parts) provides the foreground for the classic view of the Taj Mahal. The garden's strict and formal planning employs raised pathways which divide each quarter of the garden into 16 sunken parterres or flowerbeds. A raised marble water tank at the center of the garden, halfway between the tomb and the gateway, and a linear reflecting pool on the North-South axis reflect the Taj Mahal. Elsewhere the garden is laid out with avenues of trees and fountains[36].The charbagh garden is meant to symbolize the four flowing Rivers of Paradise. The raised marble water tank (hauz) is called al Hawd al-Kawthar, literally meaning and named after the "Tank of Abundance" promised to Muhammad in paradise where the faithful may quench their thirst upon arrival.[37][38] The layout of the garden, and its architectural features such as its fountains, brick and marble walkways, and geometric brick-lined flowerbeds are similar to Shalimar's, and suggest that the garden may have been designed by the same engineer, Ali Mardan.[39] Two pavilions occupy the east and west ends of the cross axis, one the mirror of the other. In the classic charbargh design, gates would have been located in this location. In the Taj they provide punctuation and access to the long enclosing wall with its decorative crenellations. Built of sandstone, they are given a tripartite form and over two storeys and are capped with a white marble chhatris supported from 8 columns.[40] The original planting of the garden is one of the Taj Mahal's remaining mysteries. The contemporary accounts mostly deal just with the architecture and only mention 'various kinds of fruit-bearing trees and rare aromatic herbs' in relation to the garden. Cypress trees are almost certainly to have been planted being popular similes in Persian poetry for the slender elegant stature of the beloved, and also symbolising death. Fruit trees conversely symbolised life and at the end of the 18th century, Thomas Twining noted orange trees. A large plan of the complex suggests beds of various other fruits such as pineapples, pomegranates, bananas, limes and apples. As the Mughal Empire declined, the tending of the garden declined as well. The British, at the end of the 19th century thinned out a lot of the increasingly forested trees, replanted the cypresses and laid the gardens to lawns in their own taste.[41] Great gate (Darwaza-i rauza) The great gate stands at the north of entrance forecourt (Jilaukhana) and provides a transition between the worldly realm of bazaars and caravanserai and the spiritual realm of the paradise garden, mosque and the mausoleum. Its rectangular plan is a variation of the 9-part hasht bihisht plan found in the mausoleum. The corners are articulated with octagonal towers giving the structure a defensive appearance. External domes were reserved for tombs and mosques of the time and so the large central space does not receive any outward expression of its internal dome. From the space the Mausoleum is framed along its major axis by the pointed arch of the portal. Inscriptions from the Qu'ran are inlaid around the two northern and southern pishtaqs, the southern one 'Daybreak' invites believers to enter the garden of paradise.[42]

Running the length of the northern side of the southern garden wall to the east and west of the great gate are galleried arcades. A raised platform with geometric paving provides their base and between the columns are cusped arches typical of the Mughul architecture of the period. The galleries were used during the rainy season to admit the poor and distribute alms. The galleries terminate at each end with a transversely placed room with tripartite divisions.[42] Forecourt (Jilaukhana)The Jilaukhana (literally meaning 'in front of house') was a courtyard feature introduced to mughal architecture by Shah Jahan. It provided an area where visitors would dismount from their horses or elephants and assemble in style before entering the main tomb complex. The rectangular area divides north-south and east-west with an entry to the tomb complex through the main gate to the north and entrance gates leading to the outside provided in the eastern, western and southern walls. The southern gate leads to the Taj Ganji quarter.[43]

Two identical streets lead from the east and west gates to the centre of the courtyard. They are lined by verandahed colonnades articulated with cusped arches behind which cellular rooms were used to sell goods from when the Taj was built until 1996. The tax revenue from this trade was used for the upkeep of the Taj complex. The eastern bazaar streets were essentially ruined by the end of the 19th century and were restored by Lord Curzon restored 1900 and 1908.[44]

Two mirror image tombs are located at the southern corners of the Jilaukhana. They are conceived as miniature replicas of the main complex and stand on raised platforms accessed by steps. Each octagonal tomb is constructed on a rectangular platform flanked by smaller rectangular buildings in front of which is laid a charbargh garden. Some uncertainty exists as to whom the tombs might memorialise. Their descriptions are absent from the contemporary accounts[j] either because they were unbuilt or because they were ignored, being the tombs of women. On the first written document to mention them, the plan drawn up by Thomas and William Daniel in 1789, the eastern tomb is marked as that belonging to Akbarabadi Mahal and the western as Fatehpuri Mahal.[45][46]

A pair of courtyards at the northern corners of the Jilaukhana provided quarters (Khawasspuras) for the tombs attendants and the Hafiz. This residential element provided a transition between the outside world and the other-worldy delights of the tomb complex. The Khawasspurs had fallen into a state of disrepair by the late 18th century but the institution of the Khadim continued into the 20th century. The Khawasspuras were restored by Lord Curzon as part of his repairs between 1900 and 1908, after which the western courtyard was used as a nursery for the garden and the western courtyard was used as a cattle stable until 2003.[43] Bazaar and caravanserai (Taj Ganji)The Bazaar and caravanserai were constructed as an integral part of the complex, initially to provide the construction workers with accommodation and facilities for their wellbeing, and later as a place for trade, the revenue of which supplemented the expenses of the complex. The area became a small town in its own right during and after the building of the Taj. Originally known as 'Mumtazabad', today it is called Taj Ganji or 'Taj Market'. Its plan took the characteristic form of a square divided by two cross axial streets with gates to the four cardinal points. Bazaars lined each street and the resultant squares to each corner housed the caravanserais in open courtyards accessed from internal gates from where the streets intersected (Chauk). Contemporary sources pay more attention to the north eastern and western parts of the Taj Ganji (Taj Market) and it is likely that only this half received imperial funding. Thus, the quality of the architecture was finer than the southern half.[47] The distinction between how the sacred part of the complex and the secular was regarded is most acute in this part of the complex.[47] Whilst the rest of the complex only received maintenance after its construction, the Taj Ganji became a bustling town and the centre of Agra's economic activity where "different kinds of merchandise from every land, varieties of goods from every country, all sorts of luxuries aof the time, and various kinds of necessitities of civilisation and comfortable living brought from all parts of the world" were sold.[48] An idea of what sort of goods might have been traded is found in the names for the caravanserais; the north western one was known as Katra Omar Khan (Market of Omar Khan), the north eastern as Katra Fulel (Perfume Market), the south western as Katra Resham (Silk Market) and the south-eastern as Katra Jogidas. It has been constantly redeveloped ever since its construction, to the extent that by the 19th century it had become unrecognisable as part of the Taj Mahal and no longer featured on contemporary plans and its architecture was largely obliterated. Today, the contrast is stark between the Taj Mahal's elegant, formal geometric layout and the narrow streets with organic, random and un-unified constructions found in the Taj Ganji. Only fragments of the original constructions remain, most notably the gates.[47] Tombs outside the walls

WaterworksWater for the Taj complex was provided through a complex infrastructure. It was drawn from the river by a series of purs - an animal-powered rope and bucket mechanism.[49] The water flowed along an arched aqueduct into a large storage tank, where, by thirteen additional purs, it was raised to large distribution cistern above the Taj ground level located to the west of the complex's wall. From here water passed into three subsidiary tanks and was then piped to the complex. The head of pressure generated by the height of the tanks (9.5m) was sufficient to supply the fountains and irrigate the gardens. A 0.25 m diameter earthenware pipe lies 1.8 m below the surface,[37] in line with the main walkway which filled the main pools of the complex. Some of the earthenware pipes were replaced in 1903 with cast iron. The fountain pipes were not connected directly to the fountain heads, instead a copper pot was provided under each fountain head: water filled the pots ensuring an equal pressure to each fountain. The purs no longer remain, but the other parts of the infrastructure have survived with the arches of the aqueduct now used to accommodate offices for the Archaeological Survey of India's Horticultural Department.[50] Moonlight garden (Mahtab Bagh)To the north of the Taj Mahal complex, across the river is another Charbagh garden. It was designed as an integral part of the complex in the riverfront terrace pattern seen elsewhere in Agra. Its width is identical to that of the rest of the Taj. The garden historian Elizabeth Moynihan suggests the large octagonal pool in the centre of the terrace would reflect the image of the Mausoleum and thus the garden would provide a setting to view the Taj Mahal. The garden has been beset by flooding from the river since Mughal times. As a result, the condition of the remaining structures is quite ruinous. Four sandstone towers marked the corners of the garden, only the south-eastward one remains. The foundations of two structures remain immediately north and south of the large pool which were probably garden pavilions. From the northern structure a stepped waterfall would have fed the pool. The garden to the north has the typical square, cross-axial plan with a square pool in its centre. To the west an aqueduct fed the garden.[51][52] See alsoNotesa. ^ The UNESCO evaluation omits the Taj Ganji and Moonlight garden from its area calculations - the total area with the historic Taj Ganji is 26.95 ha Citations

References

Further reading

External links

27°10′30″N 78°02′32″E / 27.17500°N 78.04222°E

|