University of Virginia fraternities and sororities

Fraternities and sororities at the University of Virginia include the collegiate organizations on the grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. First founded in the 1850s with the establishment of several fraternities, the system has since expanded to include sororities, professional organizations, service fraternities, honor fraternities, and cultural organizations. Fraternities and sororities have been significant to the history of the University of Virginia, including the founding of two national fraternities Kappa Sigma (ΚΣ) and Pi Kappa Alpha (ΠΚΑ).[1]

Roughly 30% of the student body belongs to a social fraternity or sorority, with additional students involved in professional, service, and honor fraternities.[2] Many of the university's fraternities and sororities are residential, meaning they own or rent a house for their members to use; many of these houses are located on Rugby Road and the surrounding streets, just north of the university.[3] Additionally, three social fraternities hold reserved rooms on the Lawn and the Range: Kappa Sigma in Room 46 East Lawn, Trigon Engineering Society in Room 17 West Lawn, and Pi Kappa Alpha in Room 47 West Range.[4] Various NPHC and MGC organizations also have Lawn rooms of historical relevance to their particular chapters as well. Reflecting UVA's tradition of student self-governance, the system is currently governed by four Greek Councils consisting of student leaders; however, it is also overseen by the Department of Fraternity and Sorority Life in the university's Office of the Dean of Students.[5]

History

Fraternities were first founded at UVA a few decades after the school's establishment in 1819. Before this time social life at the university was fixed around debating societies; the now-defunct Patrick Henry Society, for instance, initially had a membership nearly equal to the size of the student body.[6] In the 1850s the first fraternities began to appear and assumed a significant role in the student body's social landscape. In the following decades, the university became the birthplace of two national fraternities and saw many more fraternity chapters chartered.[1] The twentieth century saw the system expand even more to include professional fraternities, social sororities, local fraternities, and black fraternities and sororities.[7] Moving into the 2000s, several new social organizations were founded, and multicultural organizations began to rise to prominence.[citation needed]

1800s: Debating and secret societies

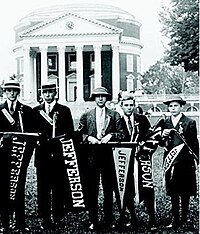

For several decades following the founding of the university, the major student societies on grounds were the debating societies.[6] Several of these societies, notably the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society and the Washington Literary Society and Debating Union, are still active today. These and other debating societies that are no longer in existence, such as the Philomathean Society and the Parthenon Society, served as the primary means of student societal activity in the early days of the university.[6]

In the decade before the Civil War, eleven fraternities established chapters at the university.[8] The first was Delta Kappa Epsilon, or DKE (ΔΚΕ), which was founded in 1852 as a "secret" colony and remains active to this day.[8] Faculty were originally against the creation of fraternities due to years of riotous behavior among the students and attacks upon faculty. According to University historian Philip Alexander Bruce, the faculty feared the "orderly spirit of the student body acting as a whole or in segments, whether organized into secret fraternities or Calathumpian bands." Despite these objections, however, a chapter of DKE was founded, and other fraternities followed.[9] It can be said generally about the early UVA fraternities that the only "secret" aspect of them was their operation and meeting location; the membership was not kept secret. As is the case with most modern fraternities, the original fraternities on grounds were meant to provide social engagement and promote close ties between members.[8]

Fraternity growth was interrupted by the Civil War, as men from many Southern colleges halted their studies to join the Confederate army. Many fraternity chapters ceased to exist during this time, but some students made efforts to preserve their fraternities as the war continued.[1] Harry St. John Dixon, a member of Sigma Chi from the University of Virginia, joined with four other Sigma Chi brothers from other universities to form the Constantine chapter of the fraternity. Created in 1864, this chapter was meant to preserve the bonds of the fraternity during the war, promote ties between the North and South, and ensure the fraternity's continued existence.[1][10]

The expansion of fraternity life resumed after the war; by 1892 there were eighteen fraternities on grounds.[11] Fraternities began to share the social spotlight with ribbon societies at the university, which was founded in reaction to the fraternities' social exclusivity. The ribbon societies, such as Eli Banana and T.I.L.K.A., were originally meant to increase social involvement among students, but eventually took on a political role in the university as well. They became particularly prestigious, mainly pulling their membership from fraternities, and election to their societies was considered a high honor.[11] Despite this social competition, fraternities continued to grow at the university.[12]

1868: Founding of Pi Kappa Alpha

Pi Kappa Alpha was founded on Sunday evening March 1, 1868, at 47 West Range at the University of Virginia, by Robertson Howard, Julian Edward Wood, James Benjamin Sclater Jr., Frederick Southgate Taylor, Littleton Waller Tazewell Bradford and William Alexander.[1][13] On March 1, 1869, exactly one year after the Alpha chapter at the University of Virginia was formed, the Beta chapter of Pi Kappa Alpha was founded at Davidson College.[14] Expanding the fraternity proved difficult because the Civil War disorganized many Southern colleges, and many colleges banned the formation of secret societies.[15][16] After almost a decade of decline, Pi Kappa Alpha was "re-founded" as part of the Hampden-Sydney Convention, held in a dorm room at Hampden–Sydney College.[17] Pi Kappa Alpha was not originally organized as a sectional fraternity; however, by constitutional provision it became so in 1889.[16] It remained a Southern fraternity until the New Orleans Convention in 1909 when Pi Kappa Alpha officially declared itself a national organization.[18] Originally, Pi Kappa Alpha's membership was restricted to white men, but the race restriction was removed in 1964.[19]

1869: Founding of Kappa Sigma

On December 10, 1869, five students at the University of Virginia met in 46 East Lawn and founded the Kappa Sigma fraternity.[1][20] William Grigsby McCormick, George Miles Arnold, John Covert Boyd, Edmund Law Rogers, Jr., and Frank Courtney Nicodemus established the fraternity based on the traditions of the Kirjath Sepher, an ancient order at the University of Bologna in the Middle Ages. These five founders became collectively known as the "Five Friends and Brothers."[20][21] In 1872, Kappa Sigma initiated Stephen Alonzo Jackson, who would go on to transform the struggling local fraternity into a strong international Brotherhood.[22] In 1873, thanks to Jackson's work, Kappa Sigma expanded to Trinity College (now Duke University),[23] the University of Maryland, and Washington and Lee University.[20] Since then, Kappa Sigma has become a large international fraternity with over 300 active chapters and colonies in North America.[24]

Early 1900s: Residences, professional and women's fraternities

In the beginning of the twentieth century the fraternity system continued to expand at such a rapid pace that university newspapers questioned if the increase in the number of fraternities would ever end.[25] Many fraternity chapters were founded during this time that no longer exist at the university, such Alpha Chi Rho, Theta Nu Epsilon, and Delta Chi. Other chapters that are still active were founded at this time as well, such as Theta Chi and Phi Sigma Kappa.[25]

Also during this time fraternities began to purchase and construct houses. During the late 1800s fraternities did not have dedicated houses; instead, they inhabited residential areas scattered around grounds, such as Dawson's Row near the Lawn and boarding houses north of the university.[26][27] In 1908, the university's Board of Visitors first offered a land lease and a $12,000 loan to Kappa Sigma to construct a fraternity house, and many other fraternities followed.[25] Most of these were located just north of the Rotunda, on Rugby Road, Madison Lane, University Place, and the surrounding streets. Some of these houses cost up to $20,000 to build, and many drew inspiration from historic UVA buildings or residences of the Old South, using elements of Jeffersonian architecture.[25][28][29] Two houses were even styled to closely resemble famous buildings in the area, with Zeta Psi's house modeled after Monticello and Farmington, and Phi Kappa Psi's house modeled after Carr's Hill.[28][30][31] By 1916 most fraternities had built, purchased, or rented a house for their members.[25]

Around the turn of the century, scholastic honor organizations appeared on grounds. The university chapter of Phi Beta Kappa (ΠΒΚ) was founded in 1908, promoting scholarship in all fields of study.[25] Different schools had specific honor and professional societies as well: Phi Delta Phi (ΦΔΦ) for the law department, Phi Rho Sigma (ΦΡΣ) for medicine, Kappa Delta Mu for chemistry, and many others.[25] A chapter of Theta Tau (ΘΤ), an engineering society, was founded in 1923, and Trigon Engineering Society was founded in 1924 as a local fraternity for engineering students.[25][32] Trigon and Theta Tau dominated student government in the Engineering School during this time, often fielding competing candidates for student office. Likewise in the College, the University Party and the Cavalier Party were dominated by Lambda Pi and Skull & Keys.[33]

It was during the first half of the twentieth century that the first women's fraternities were established. The university first admitted women to graduate programs in 1920, although undergraduate women were not allowed at the university until much later.[34][35] With these graduate women came several organizations for women, referred to alternately as sororities or women's fraternities. The first sorority to establish a chapter at the university was Chi Omega (ΧΩ), whose chapter was founded in 1927.[34] A Kappa Delta (ΚΔ) chapter followed in 1932, and a chapter of Zeta Tau Alpha (ΖΤΑ) was established twenty years later in 1952.[34]

In 1947, with the inauguration of Colgate Darden as president of the university, first-year students were prohibited from joining fraternities and sororities.[36] This restriction was later eased to a one-semester prohibition, which is still in place today.[37] During this time only 20 percent of students were members of the 24 fraternities on grounds.[38] Darden was critical of the fraternities' behavior, arguing in a 1949 report to the Board of Visitors that the groups had failed to uphold the interests of the university community and to provide the leadership expected of them.[36] Additionally, university leaders condemned the fraternities' treatment of their houses, which were extremely run down. Members would often solicit tens of thousands of dollars of donations from alumni to refurbish houses, only to see the improvements disappear within a few years.[36] Despite the administrators' concerns, this problem was not addressed until 1983, when the university created the Historic Renovation Corporation, or HRC.[36] The HRC, which later became a subsidiary of the UVA Foundation, renovates and manages the properties of several fraternity and sorority houses.[39]

Late 1900s

Easters

The 1970s saw great upheaval as fraternities, whose membership had been waning, began to increase in size. In 1973, nearly 45 percent of freshmen joined fraternities, the highest percentage in school history, and with this increased membership disruptive behavior increased on campus.[40] In the 1970s the annual tradition of Easters' parties, which began in the 1800s as formal dances sponsored by the ribbon societies, had evolved into a weekend-long celebration where fraternities would flood Mad Bowl and the surrounding areas, creating huge mud pits for the event.[35][41] By 1976, it was estimated that 15,000 people had come from up and down the East Coast to fill the Mad Bowl.[41] Students washing off mud led to clogged drainage systems in the university, and entire dorms were flooded.[35][41] Eventually the event became so unmanageable that, in 1982, the university terminated Easters.[40][41]

African Americans

African Americans were originally admitted to the university in the mid-1950s, but few attended until the 1970s; fraternities at this time were generally racially and religiously segregated.[35] Although a student fraternity committee emphasized the fraternities' rejection of racial discrimination, in 1969 only 5 of 578 fraternity pledges were black.[35] African-American fraternities and sororities soon established chapters at the university, although they presented themselves as service organizations rather than traditional social organizations.[35] In the mid-1970s, although some black students were invited to join the heavily white fraternities, many preferred to join their own organizations. By the fall of 1973, four black fraternities, the Lambda Zeta chapter of Omega Psi Phi (ΩΨΦ), the Eta Sigma chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi (ΚΑΨ), the Iota Beta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha (ΑΦΑ), and the Zeta Eta chapter of Phi Beta Sigma (ΦΒΣ), and one black sorority, Kappa Rho (ΚΡ) chapter of Delta Sigma Theta (ΔΣΘ), had established chapters on grounds.[35]

Women's organizations

In 1970 the College of Arts and Sciences allowed the first women to enroll in its undergraduate programs, which effectively made the university coeducational.[34][35] This led to the rapid establishment of many social sororities at the university, and by the end of the 1970s there were eleven sorority chapters at the university, with still more chartered in the 1980s.[34]

In 1975 the sororities established the Inter-Sorority Council, or ISC, to govern the increasing number of sororities on grounds. The ISC was founded to continue the tradition of student self-governance and was similar to the university's Inter-Fraternity Council (IFC) in its function. The organization was named the Inter-Sorority Council to mimic the name of the Inter-Fraternity Council, which fraternities had established in 1934; this was meant to emphasize sorority women's equality with fraternity men.[34] Later, in 2005, the ISC voted to formally associate with the National Panhellenic Conference, the national governing body of social sororities. Despite this change, the ISC at the university retained its name due to its historical heritage.[34]

2000 onward: Multicultural fraternities

The first decade of the 2000s saw a quick rise in the number of multicultural organizations at UVA. In 1999, the first Latina and Asian-interest sorority chapters were founded at UVA, Omega Phi Beta (ΩΦΒ) and alpha Kappa Delta Phi (αΚΔΦ), respectively.[7] The university's first Latino fraternity, a chapter of Lambda Upsilon Lambda (ΛΥΛ), was founded later that same year.[7] These three organizations founded the Fraternity-Sorority Council, which was meant to organize the newly created multicultural organizations; in 2000, this group was renamed the Multicultural Greek Council, or MGC, and the council exists to this day.[7] With the creation of additional cultural fraternities and sororities, the MGC has grown to a total of 11 organizations.[42]

In 2002 the IFC decided to admit local fraternities, fraternities that are not affiliated with a national organization, for the first time (although local fraternities had existed at UVA before this time, they had not been permitted to join the IFC).[43] Two years prior, when the Phi Delta Theta (ΦΔΘ) national organization decided to ban alcohol consumption in its chapter houses, the UVA chapter broke away from its national organization and created local organization Phi Delta Alpha, which was later renamed Phi Society.[44] After debate within the IFC, Phi Society was admitted and recognized by the university as a local fraternity. Phi Society is viewed as the continuation of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity that existed before 2000 and maintains the same house.[45] In 2001, Phi Delta Theta established another chapter at the university that adheres to its directives concerning alcohol consumption.[46] The Greek system's expansion to new groups continued in 2015, as local fraternity Sigma Omicron Rho became the first gender-inclusive and LGBTQ fraternity to be recognized by the university, with the organization later on rebranding itself as a diaternity during its process of getting incorporated.[47]

Governance

University recognition

University policy prevents national fraternities and sororities from directly establishing a chapter at the university; instead, an interested group of students must establish an interest group, petition for the establishment, and obtain sponsorship from one of the Greek councils.[48][49] Once sponsorship is obtained, a group enters the provisional phase of the process; at this point the interest group may contact a national fraternity or sorority to begin the process of establishing themselves as a colony or chapter. Upon successful completion of the provisional phase, the organization is granted full membership in its chosen Greek council.[49]

To maintain a formal relationship with the university, each organization must annually complete a Fraternal Organization Agreement (FOA). Fraternal organizations can exist without signing an FOA, however, signing an FOA grants additional benefits to organizations, including the ability to use certain university spaces and to join a Greek council.[50]

Greek councils

Several councils at UVA oversee the functions of their member organizations. While most fraternal organizations are members of a Greek council, several organizations are independent of these councils, mainly coeducational organizations, professional fraternities, and honor societies. Traditionally, a student is not allowed to join more than one social fraternity or sorority; however, students are normally allowed to join independent fraternities or sororities (mainly professional or honor organizations) in addition to a social fraternity or sorority.[51] The four Greek councils at the University of Virginia are as follows:

Active councils

- The Inter-Fraternity Council, or IFC, is the oldest of the Greek councils. Founded in 1934, the IFC oversees 32 social fraternities and is led by a governing board that is elected by the brothers of the member fraternities. The IFC works with the President's Council, which consists of fraternity chapter presidents, to govern the fraternity community.[52]

- The Inter-Sorority Council, or ISC, is the governing body of the majority of UVA's social sororities. The ISC was founded in 1975, is entirely student-run, and consists of 16 member sororities.[34]

- The National Pan-Hellenic Council, or NPHC, was formed to unite the traditionally black organizations on grounds. The NPHC was originally known as the Black Fraternal Council, which was established in 1973 by the charter of Omega Psi Phi fraternity and re-charted in 1991. In 2005, the BFC was renamed the National Pan-Hellenic Council. These member organizations include 7 total all-male fraternities and all-female sororities.[53] UVA's NPHC is not to be confused with the National Panhellenic Conference, which is the national governing body of social sororities.

- The Multicultural Greek Council, or MGC, is the youngest of the Greek councils and comprises the multicultural Greek organizations on grounds. Founded in 1999, the MGC is composed of 11 total single-sex and coeducational organizations. Each of these organizations emphasizes a particular race or culture, particularly Asian or Latino culture; however, while these organizations may have a certain cultural emphasis, membership is generally open to students of any race.[54] The council was formerly named the Fraternity Sorority Council and is not to be confused with the National Multicultural Greek Council, the national governing body for various multicultural Greek-lettered organizations.

Dormant councils

- Greek Jewish Council, or GJC, is a currently dormant Greek Council that has historically been active several times in the history of the University of Virginia. The council was last re-chartered in 2001.[55]

Controversies

Rolling Stone article

In 2014 the University of Virginia fraternity and sorority system became the focus of significant national scrutiny due to the publication of an article in the December 2014 issue of Rolling Stone magazine, entitled "A Rape on Campus" and authored by Sabrina Erdely. The article alleged that in September 2012, a group of male fraternity members at the university had attacked and raped a female student as part of an initiation rite at a party at the university's chapter of Phi Kappa Psi. The article further asserted that the university's sexual assault policies were severely lacking and that the university administration did not handle sexual assault cases appropriately.[56] The article attracted significant media attention and made national headlines, leading to the suspension of the university's Greek system and further investigation into the article's claims; these investigations quickly revealed numerous inconsistencies and raised serious questions about the article's veracity. On January 12, 2015, Charlottesville Police Department officials told the university that "their investigation has not revealed any substantive basis to confirm that the allegations raised in the Rolling Stone article occurred at Phi Kappa Psi...so there's no reason to keep them suspended".[57][58] On January 30, 2015, UVA President Teresa Sullivan acknowledged that the Rolling Stone story was discredited.[59] Charlottesville Police officially suspended their four-month investigation on March 23, 2015, stating that they had no evidence of a gang rape taking place, and that "there is no substantive basis to support the account alleged in the Rolling Stone article."[60] On April 5, 2015, Columbia Journalism Review published a report calling the Rolling Stone article "a failure" and criticizing the magazine's actions. That same day, Rolling Stone officially retracted the article and has since issued multiple apologies for the story.[61]

Sigma Lambda Upsilon/Señoritas Latinas Unidas Sorority, Inc. v. The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

In 2019, the Alpha Rho chapter of the Latina-interest sorority Sigma Lambda Upsilon and UVA were the centers of a notable debate highlighting what constitutes hazing in colleges and universities and the enforcement of anti-hazing policies.[62] The sorority was accused by UVA of violating its anti-hazing policy by requiring its members to complete mandatory study hours of at least 25 hours per week.[63] This was met with the sorority's national organization filing a lawsuit against the university, in which they argued that the mandatory study hours were not hazing and that the university's definition of hazing was too broad.[64] The lawsuit additionally accused UVA of discrimination against the sorority because of its focus on serving the Latina community. UVA's decision to classify mandatory study hours as hazing was met with criticism from several writers and media outlets. The National Review published an article arguing that the lawsuit against Sigma Lambda Upsilon was a sign of the "hazing hysteria" that has taken hold on university and college campuses.[65] Also reporting on the controversy, The Washington Post and NBC News highlighted the debate over what constitutes hazing and the controversy over UVA's decision to classify mandatory study hours as hazing.[66][67] A local columnist, Kerry Dougherty, in Virginia, also weighed in on the controversy, arguing that UVA was "making a mockery" of the anti-hazing policy by equating mandatory study hours with hazing.[68]

In response to the lawsuit filed by Sigma Lambda Upsilon's national organization, the university defended its anti-hazing policies and argued that UVA's definition of hazing was consistent with that used by other colleges and universities.[69] The university also emphasized its commitment to promoting diversity and inclusion on grounds, but argued that this commitment did not excuse violations of the university's policies. The case was ultimately settled out of court in 2019, with Sigma Lambda Upsilon agreeing to implement new anti-hazing policies and UVA agreeing to review its policies and procedures related to hazing.

Social fraternities

The University of Virginia has a large number of social fraternities. This list includes active all-male fraternities and coeducational fraternities that identify themselves primarily as social organizations, as opposed to professional, service, or honor organizations. Several of these fraternities were founded much earlier in the university's history, but went inactive and were reestablished later on. In these cases, the establishment date reflects the date that the fraternity's original charter was granted.

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Delta Phi

(ΑΔΦ) |

Not residential | 1855 | IFC | The Virginia chapter of Alpha Delta Phi was originally established in 1855 but was revoked two years later in the prelude to the Civil War. Its second charter was granted in 1987, but the chapter lost its charter again in 2003. The current chapter is the third incarnation, founded in 2010. | [2][70][71] |

| Alpha Epsilon Pi

(ΑΕΠ) |

|

November 29, 1924 | IFC | Alpha Epsilon Pi, or "A E Pi," is a primarily Jewish fraternity that was founded at UVA in 1924 as a Mu chapter. It obtained its original house in 1935 and moved into its current house in 1962. Although it lost its charter in 2010, it was recolonized in 2012. The organization has historically been involved with the Greek Jewish Council which was last re-chartered in 2001. | [2][72][73] |

| Alpha Phi Alpha

(ΑΦΑ) |

Not residential | March 10, 1974 | NPHC | The Iota Beta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha is one of five African-American fraternities at the university. The chapter was established at UVA in 1974. | [2][74] |

| Alpha Sigma Phi

(ΑΣΦ) |

Not residential | September 20, 2013 | IFC | The Zeta Upsilon chapter of Alpha Sigma Phi is the newest fraternity at the university and was established in 2013. | [2][75] |

| Alpha Tau Omega

(ΑΤΩ) |

|

November 25, 1868 | IFC | The university's Virginia Delta chapter of Alpha Tau Omega, or "ATO," was founded in 1868. | [2][76] |

| Beta Theta Pi

(ΒΘΠ) |

|

April 24, 1855 | IFC | The Omicron chapter of Beta Theta Pi, or "Beta," is one of the oldest fraternities at the university and was founded in 1855. It owned a house on Rugby Road until its charter was revoked briefly in 1972, at which time the house was purchased by Delta Upsilon and Beta moved south of grounds. After DU moved in 2010, Beta repurchased the house, in which it currently resides. The adjacent Beta Bridge takes its name from Beta's nearby house. | [2][77] |

| Chi Phi

(ΧΦ) |

|

May 1859 | IFC | Chi Phi at the University of Virginia was originally a chapter of the Southern Order of Chi Phi, founded at the University of North Carolina in 1858. The modern Chi Phi fraternity was established in 1874 by the merger of three separate fraternities around the country, all bearing the name Chi Phi. Although the fraternity was not founded at the University of Virginia, the UVA chapter is considered the Alpha chapter because it is the oldest chapter of the original three organizations: the Princeton Order of Chi Phi, founded at Princeton University, ceased to exist in 1859, the University of North Carolina chapter of the Southern Order ceased to exist during the Civil War, and the Northern Order, founded at Hobart College, was established in 1860, after the University of Virginia chapter. | [2][78] |

| Chi Psi

(ΧΨ) |

|

April 10, 1860 | IFC | The Omicron chapter of Chi Psi, also referred to as "The Lodge," was founded at the university in 1860. It went dormant during the Civil War and reformed in 1868, but went dormant again in 1872. It re-founded in 1949 and purchased Charlottesville's former country club on Rugby Rd Extended to use as its Lodge for more than 50 years. After becoming inactive in 2008, it was re-founded in 2015. | [79][80] |

| Delphic of Gamma Sigma Tau

(ΓΣΤ) |

|

March 29, 2009 | MGC | The university's Kappa chapter is the only extant undergraduate chapter of Delphic and the first all-male multicultural fraternity on grounds. It was founded in 2009 by a local fraternity interest group known as the Brotherhood of All Men. It is the second residential MGC organization. | [42][81] |

| Delta Kappa Epsilon

(ΔΚΕ) |

|

November 26, 1852 | IFC | The Eta chapter of Delta Kappa Epsilon, better known as "DKE" or "Deke," was the first fraternity established at the University of Virginia. It obtained its house in 1914 and has remained there since. | [2][82][83] |

| Delta Sigma Phi

(ΔΣΦ) |

|

May 14, 1921 | IFC | The Alpha Mu chapter of Delta Sigma Phi, also known as "Delta Sig," was established at UVA in 1921. | [2][84] |

| Delta Upsilon

(ΔΥ) |

|

April 8, 1922 | IFC | The university's chapter of Delta Upsilon, better known as "DU," was founded as the Delta Alpha Social Society. In 1922 it was given a charter as the Virginia chapter of Delta Upsilon. During World War II the chapter closed temporarily and was reopened in 1949. In 1969 its house on Rugby Road was destroyed by arson. It moved temporarily, and when Beta's charter was revoked in the 1970s, DU purchased Beta's former house next to Beta Bridge. In 2010, DU constructed its current fraternity house, the first to be constructed at the university in over fifty years. | [2][85] |

| Kappa Alpha Order

(ΚΑ) |

|

November 19, 1873 | IFC | Kappa Alpha Order, better known as "KA," was chartered as the Lambda chapter at UVA in 1873. It originally resided on University Circle and planned to build a replica of Robert E. Lee's Stratford Hall as its official fraternity house; however, plans fell through and the university's Alumni Hall was built on the site soon after. KA's next house burned down in 1958, and soon afterward they moved into their current house on Rugby Road. | [2][86] |

| Kappa Alpha Psi

(ΚΑΨ) |

Not residential | December 7, 1974 | NPHC | Kappa Alpha Psi is one of five black fraternities on grounds, founded in 1974. It was chartered as the Eta Sigma chapter by Linwood Jacobs, an associate professor, and associate dean who was responsible for facilitating the establishment of the Pan Hellenic Council at the university, and was quickly filled by university students. | [2][87] |

| Kappa Sigma

(ΚΣ) |

|

December 10, 1869 | IFC | Kappa Sigma was nationally founded at the University of Virginia on December 10, 1869, in Room 46 East Lawn. The fraternity has since spread to hundreds of other schools. Kappa Sigma constructed one of the first fraternity houses on grounds, in which it still resides today. It is known as the Zeta chapter. The university has granted Room 46 East Lawn to Kappa Sigma as a reserved room, and the fraternity selects one member each year to live in the residence. | [2][4][88] |

| Lambda Upsilon Lambda

(ΛΥΛ) |

Not Residential | December 10, 1999 | MGC | Lambda Upsilon Lambda, or La Unidad Latina, a Latino fraternity (although open to all ethnicities and races), established its Alpha Epsilon chapter on grounds in 1999 and is a founding member of the Multicultural Greek Council. It has at times served as the third residential MGC organization, although the residence of its members has varied throughout the chapter's history. Additionally, Room 33 West Lawn has historically been lived in by many of the fraternity's fourth-year members. | [2] |

| Lambda Phi Epsilon

(ΛΦΕ) |

|

March 16, 2002 | MGC | Lambda Phi Epsilon, or "Lambda," established its Alpha Tau chapter at the University of Virginia in 2002. Lambda is an Asian-American interest fraternity, although students of all races are welcome to join; it is also the first residential MGC organization. | [2][89][90] |

| Omega Psi Phi

(ΩΨΦ) |

Not residential | September 7, 1973 | NPHC | The UVA chapter, Lambda Zeta of Omega Psi Phi was established in 1973. | [2] |

| Phi Beta Sigma

(ΦΒΣ) |

Not residential | April 17, 1974 | NPHC | The university's chapter, Zeta Eta of Phi Beta Sigma was established in 1974. The chapter became inactive in 1993 but returned in 2000. | [2][91] |

| Phi Delta Theta

(ΦΔΘ) |

|

March 15, 1873 | IFC | Phi Delta Theta was established at the university in 1873. The chapter name is Virginia Beta. | [2][45] |

| Phi Gamma Delta

(ΦΓΔ) |

|

December 31, 1858 | IFC | Phi Gamma Delta, better known as "Fiji," established its Omicron chapter at the university in 1858. It went dormant in 1998 and was rechartered in 2004.[92] | [2] |

| Phi Kappa Psi

(ΦΚΨ) |

|

December 8, 1853 | IFC | The university's chapter, Virginia Alpha of Phi Kappa Psi was established in 1853 and is one of the oldest fraternities on grounds. The chapter counts among its alumni Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States. Its house is modeled after Carr's Hill, the nearby historic house of the university's president. The chapter has also been a source of controversy, most recently due to an article published by Rolling Stone magazine but since retracted and discredited. | [2][28][61][93] |

| Phi Sigma Kappa

(ΦΣΚ) |

|

1907 | IFC | The university's Psi chapter of Phi Sigma Kappa, better known as "Phi Sig," was founded in 1907. | [2] |

| Phi Society

(Φ) |

|

2000 | IFC | Phi Society is the only local fraternity recognized by the IFC. When the national organization of Phi Delta Theta banned alcohol consumption in chapter houses in 2000, the University of Virginia chapter broke away from its national organization and established itself as Phi Delta Alpha, a local fraternity, while maintaining alumni support, past composites, and the 1 University Circle house. Without a national charter, the local fraternity was derecognized by the IFC. The newly formed Phi Delta Alpha fraternity then obtained recognition with the university's Multicultural Greek Council and was readmitted to the IFC in 2003. In 2002 the fraternity changed its name to Phi Society, remaining the Virginia Beta chapter. | [2][44][45][94] |

| Pi Kappa Alpha

(ΠΚΑ) |

|

March 1, 1868 | IFC | Pi Kappa Alpha, better known as "Pike," is one of two national fraternities founded at UVA, the other being Kappa Sigma. Pike was founded in 1868 in Room 47 West Range. The second chapter was then founded at Davidson College, and the third at William and Mary. The fraternity resides in a house on Rugby Road. UVA's chapter is named Virginia Alpha. The university has granted Room 47 West Range to Pi Kappa Alpha as a reserved room, and the fraternity selects one member each year to live in the residence. | [4][95][96] |

| Pi Kappa Phi

(ΠΚΦ) |

|

March 6, 1961 | IFC | The UVA chapter, Beta Upsilon of Pi Kappa Phi was founded in 1961. | [2] |

| Pi Lambda Phi

(ΠΛΦ) |

|

November 12, 1932 | IFC | Pi Lambda Phi, better known as "Pi Lam," founded a chapter, Omega Alpha, at UVA in 1932. During World War II the chapter membership began to decline, and the chapter was rechartered in 1969. | [2][97][98] |

| Sigma Alpha Epsilon

(ΣΑΕ) |

|

December 19, 1857 | IFC | The university's chapter, Virginia Omicron of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, better known as "SAE," was founded in 1857. The chapter did not survive the Civil War but was refounded soon after. It again folded in 1878, but was re-established yet again. The fraternity purchased a house at 1703 Grady Avenue in 1936 and recently moved to its current house in 2006. | [2][99] |

| Sigma Alpha Mu

(ΣΑΜ) |

|

1968 | IFC | The Beta Psi chapter of Sigma Alpha Mu, better known as "Sammy," was founded in 1968 and re-founded in 2005. It has moved residences multiple times during its history and is historically Jewish. It has historically been involved with the Greek Jewish Council at the university. | [2][100] |

| Sigma Chi

(ΣΧ) |

|

December 10, 1860 | IFC | The Psi chapter of Sigma Chi was founded at UVA in 1860. The chapter became disorganized during the Civil War, although it was reorganized afterward. During the war, Harry St. John Dixon, one of the chapter's members, created the Constantine chapter to preserve the fraternity in the South after the war and to maintain bonds between the North and South. The Sigma Chi house is named the Constantine Memorial Chapter House in his honor. | [1][2][10][101] |

| Sigma Nu

(ΣΝ) |

|

January 1, 1871 | IFC | Established in 1871, the Beta chapter of the Sigma Nu Fraternity has a rich history. Founded on the values of love, honor, and truth, the brothers of Sigma Nu have shown their commitment to UVA and the greater Charlottesville community through community service, extracurricular activities, and academic excellence. | |

| Sigma Phi Society

(ΣΦ) |

|

February 27, 1954 | IFC | The university's chapter of Sigma Phi Society, also known as "SERP," was formed from a local fraternity called the Serpentine Club in 1953. The chapter, Alpha of Virginia, occupies the house formerly used by UVA's chapter of Delta Tau Delta. The UVA chapter was the first chapter of the fraternity to be founded below the Mason–Dixon line. | [2][102] |

| Sigma Pi

(ΣΠ) |

|

April 4, 1959 | IFC | The Beta Pi chapter of Sigma Pi was founded at UVA in 1959. | [2] |

| St. Anthony Hall

(ΔΨ) |

|

April 20, 1860 | IFC | The Upsilon chapter of St. Anthony Hall, better known as "The Hall," was founded in 1860. It closed in 1861 at the beginning of the Civil War and did not reactivate until 1866. | [2][103] |

| St. Elmo Hall

(ΔΦ) |

|

January 1908 | IFC | St. Elmo Hall, better known as "Elmo," established its Rho chapter at UVA in 1908. During World War II the entire chapter of St. Elmo Hall joined the armed forces, but after the war, several members returned to UVA to revive the chapter. When the houses of Elmo and other fraternities began to deteriorate in the 1980s, alumni of St. Elmo Hall prompted the founding of the Historical Renovation Corporation, which works to maintain and improve the houses in question. | [2][104] |

| Tau Kappa Epsilon

(ΤΚΕ) |

Not residential | December 3, 1950 | IFC | Tau Kappa Epsilon, better known as "Teke" or "TKE," founded its Gamma Omicron chapter at UVA in 1950. After 'Operation Equinox,' where a few fraternities including TKE were targeted for drug use and distribution, the chapter folded after its house at 1508 Grady Ave was seized by the federal government.[105] It was re-established in 2012. | [2][106] |

| Theta Chi

(ΘΧ) |

|

January 26, 1914 | IFC | Theta Chi was founded as local fraternity Eta Pi Rho in 1913, and was granted a charter as the Xi chapter of Theta Chi in 1914. It was originally located on Carr's Hill but moved to its current house on Preston Place in 1968. | [2][107] |

| Theta Delta Chi

(ΘΔΧ) |

|

1857 | IFC | Theta Delta Chi, also known as "Theta Delt" and "TDX," established a chapter, Nu Charge, at UVA in 1857. They occupy the old family home of William Lambeth, after whom Lambeth Field and the Lambeth Commons are named. | [2] |

| Trigon Engineering Society

(ΓΔΕ) |

|

November 3, 1924 | Independent | Trigon Engineering Society, better known as "Trigon," is a coed social fraternity for engineering students. It was founded in 1924 as the Delta Society, a political society at UVA, but quickly decided to pursue fraternal activities as well, adopting the name Trigon, the Greek letters Gamma Delta Epsilon, a handshake, pin, motto, and other fraternal symbols. Although the society was particularly involved in student government during the first half of the twentieth century, it dropped its political mission in the 1960s. The university has granted Room 17 West Lawn to Trigon as a reserved room, and the society picks one member each year to live in the residence. | [4][32][33] |

| Zeta Beta Tau

(ΖΒΤ) |

|

1915 | IFC | The university's Chi chapter of Zeta Beta Tau, or "ZBT," was founded at UVA in 1915. | [2] |

| Zeta Psi

(ΖΨ) |

|

July 28, 1868 | IFC | Zeta Psi, or "Zete," founded its Beta chapter at UVA in 1868. The architectural design of its house draws heavily from Jefferson's design of Monticello. | [2][28][108] |

Social sororities

In addition to social fraternities, the University of Virginia has a large number of social sororities. This list includes active all-female sororities that identify themselves primarily as social organizations, as opposed to professional, service, or honor organizations. All-female Greek organizations that refer to themselves as "women's fraternities" are included in this list as well.

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Chi Omega

(ΑΧΩ) |

|

April 19, 1980 | ISC | Alpha Chi Omega, better known as "AXO," founded the Zeta Lambda chapter at UVA in 1980. | [2] |

| Alpha Delta Pi

(ΑΔΠ) |

|

April 16, 1977 | ISC | Alpha Delta Pi, or "ADPi," established its UVA chapter, Zeta Xi, in 1977. | [2] |

| Alpha Kappa Alpha

(ΑΚΑ) |

Not residential | February 9, 1974 | NPHC | Alpha Kappa Alpha is the oldest historically Black sorority. It established its UVA chapter, Theta Kappa, in 1974. | [2][7][109] |

| alpha Kappa Delta Phi

(αΚΔΦ) |

Not residential | November 13, 1999 | MGC | alpha Kappa Delta Phi is an Asian-American interest sorority; it established its UVA chapter, Sigma, in 1999 thanks to the actions of the Young Asian Women's Alliance at the university. It is one of the founding members of the Fraternity-Sorority Council, which later became the MGC. | [2][7][110] |

| Alpha Phi

(ΑΦ) |

|

December 2, 1978 | ISC | The university's chapter of Alpha Phi, Zeta Iota, was founded in 1978. | [2] |

| Chi Omega

(ΧΩ) |

|

June 4, 1927 | ISC | Chi Omega was the first sorority founded at the University of Virginia, in 1927, after women were allowed to enter graduate programs at the university. Its chapter designation is Lambda Gamma. | [2][34] |

| Delta Delta Delta

(ΔΔΔ) |

|

September 27, 1975 | ISC | Delta Delta Delta, better known as "Tri-Delt," established a chapter, Beta Sigma at UVA in 1975. | [2] |

| Delta Gamma

(ΔΓ) |

|

November 18, 1978 | ISC | The university's chapter of Delta Gamma, better known as "DG," was founded in 1978 as the Epsilon Gamma chapter. Since 1980, the sorority has had a house on Madison Lane. | [2][111] |

| Delta Sigma Theta

(ΔΣΘ) |

Not residential | November 29, 1973 | NPHC | The UVA chapter, Kappa Rho of Delta Sigma Theta was founded in 1973 and was the first African-American sorority at the university. | [2][7][112] |

| Delta Zeta

(ΔΖ) |

|

November 12, 1977 | ISC | The Lambda Delta chapter of Delta Zeta, better known as "DZ," was founded at UVA in 1977. | [2] |

| Gamma Phi Beta

(ΓΦΒ) |

|

April 9, 1994 | ISC | Gamma Phi Beta established its Zeta Beta chapter at UVA in 1994. | [2] |

| Kappa Alpha Theta

(ΚΑΘ) |

|

April 3, 1976 | ISC | The Delta Chi chapter of Kappa Alpha Theta, better known as "Theta," was founded at UVA in 1976. | [2] |

| Kappa Delta

(ΚΔ) |

|

June 5, 1932 | ISC | The Beta Alpha chapter of Kappa Delta, better known as "KD," was established at UVA in 1932, and is the second-oldest sorority at the university. | [2][34] |

| Kappa Kappa Gamma

(ΚΚΓ) |

|

October 23, 1976 | ISC | The university's Epsilon Sigma chapter of Kappa Kappa Gamma, better known as "Kappa," was established in 1976. | [2] |

| Lambda Theta Alpha

(ΛΘΑ) |

Not residential | April 29, 2001 | MGC | The Gamma Alpha chapter of Lambda Theta Alpha was established at UVA in 2001 by an interest group called the Sisters of Diversity. Lambda Theta Alpha is a Latina sorority. | [2][113] |

| Omega Phi Beta

(ΩΦΒ) |

Not residential | October 25, 1998 | MGC | The Iota chapter of Omega Phi Beta was established at UVA in 1998 as the Latina sorority on grounds. | [2][114][115] |

| Pi Beta Phi

(ΠΒΦ) |

|

April 30, 1975 | ISC | Pi Beta Phi, better known as "Pi Phi," established the university's chapter, Virginia Epsilon in 1975. Pi Phi was the first national sorority to be established at UVA after the university became coeducational in 1969, although several sororities existed at UVA before that time. Pi Phi purchased its chapter house in 1975. | [2][116] |

| Sigma Delta Tau

(ΣΔΤ) |

Resides 1505 Virginia Ave | April 9, 2011 | ISC | Sigma Delta Tau, also known as "Sig Delt" and "SDT," established its Beta Rho chapter at UVA in 2011. It is a historically Jewish sorority. | [2] |

| Sigma Kappa

(ΣΚ) |

|

April 16, 1987 | ISC | Sigma Kappa, also known as "SK," established its Theta Zeta chapter at UVA in 1987. | [2] |

| Sigma Lambda Upsilon

(ΣΛΥ) |

Not residential | March 23, 2013 | MGC | UVA's chapter of Sigma Lambda Upsilon, a Latina sorority, was established in 2013. Its chapter designation is Alpha Rho. | [2] |

| Sigma Psi Zeta

(ΣΨΖ) |

Not residential | December 1, 2001 | MGC | Sigma Psi Zeta, an Asian-interest sorority, established its Lambda chapter at UVA in 2001. The chapter evolved from an Asian interest group called Sisterhood of Young Asians. | [2][117] |

| Sigma Sigma Sigma

(ΣΣΣ) |

|

April 23, 1981 | ISC | The university's chapter of Sigma Sigma Sigma, better known as "Tri-Sig," was established in 1981. Its chapter name is Delta Chi. | [2] |

| Theta Nu Xi

(ΘΝΞ) |

Not residential | December 7, 2002 | MGC | Theta Nu Xi, a multicultural sorority, established its Pi chapter at UVA in 2002. | [2] |

| Zeta Phi Beta

(ΖΦΒ) |

Not residential | April 2, 1978 | NPHC | Zeta Phi Beta is one of four black sororities on grounds, and the UVA chapter, Tau Theta, was established in 1978. | [2] |

| Zeta Tau Alpha

(ΖΤΑ) |

|

January 5, 1952 | ISC | The Gamma Nu chapter of Zeta Tau Alpha, better known as "Zeta," was established at UVA in 1952. | [2] |

Social diaternities

The University of Virginia currently hosts one of four social diaternities in the United States, the Alpha chapter of Sigma Omicron Rho LGBTQ & Allied Gender-Inclusive Diaternity. This list includes active coeducational Greek-lettered organizations that identify themselves primarily as social organizations, as opposed to professional, service, or honor organizations. The establishment date reflects the date that the organization was originally founded as a local coeducational fraternity prior to its attempts of becoming incorporated.

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sigma Omicron Rho

(ΣΟΡ) |

Not Residential | August 2009 | MGC | The Alpha chapter of Sigma Omicron Rho is currently the only LGBTQ diaternity at UVA and was the first co-educational Greek-lettered organization to be recognized by the university. Founded in 2009 as a local fraternity, Sigma Omicron Rho existed independently of the Greek councils for several years before gaining recognition with the MGC in 2015. It is currently in the process of becoming incorporated and is one of four organizations in the United States to refer to itself as a diaternity (meaning "transcending boundaries"), a term originally coined in 2014 by Lambda Delta Xi Diaternity, Inc. at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania. | [47][118][119] |

Service fraternities, professional fraternities, and honor societies

The University of Virginia also has chapters of numerous Greek organizations whose primary focus is not social, although some offer social events in addition to service or academic events. While membership in professional fraternities is generally open to any student studying that profession, membership requirements for honor societies are often more demanding and require specific academic or extracurricular achievements.[120]

Service fraternities

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Phi Omega

(ΑΦΩ) |

Not residential | February 9, 1929 | Independent | Alpha Phi Omega, better known as APO, is a coed service fraternity. The UVA chapter is Theta. | [121] |

Professional fraternities

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Chi Sigma

(ΑΧΣ) |

|

May 27, 1922 | Independent | Alpha Chi Sigma is a professional chemistry fraternity. The UVA chapter is Alpha Kappa. | [122] |

| Alpha Kappa Psi

(ΑΚΨ) |

Not residential | June 3, 1921 | Independent | AKPsi is a coed professional business fraternity whose chapter was founded at UVA in the early twentieth century. The UVA chapter is designated Alpha Gamma. | [123] |

| Alpha Omega Epsilon

(ΑΩΕ) |

Not residential | April 23, 2005 | Independent | Alpha Omega Epsilon, or AOE, is a professional engineering sorority that established its Pi chapter at UVA in 2005. It is the only engineering sorority at the university. | [124] |

| Phi Alpha Delta (ΦΑΔ) | Not residential | 1925 | Independent | Phi Alpha Delta, or ΦΑΔ, is a professional international law and pre-law fraternity. This chapter is in district XXIV. | |

| Theta Tau

(ΘΤ) |

Not residential | May 26, 1923 | Independent | Theta Tau is a coed professional engineering fraternity that established its Pi chapter at UVA in 1923. In the first half of the twentieth century, it was particularly active in student government of the Engineering School, along with Trigon, which was its rival organization at the time. | [33][125] |

Honor societies

| Name | House image | Charter date at UVA | Council | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting Society at McIntire | Not residential | Independent | The Accounting Society at McIntire began as the Delta Mu chapter of Beta Alpha Psi, an honor society for finance students. It changed its name in 2015. | [126][127][128] | |

| Alpha Alpha Alpha

(ΑΑΑ) |

Not residential | November 9, 2023 | Independent | Alpha Omega Alpha is an honorary first-generation student society. | |

| Alpha Epsilon Delta

(ΑΕΔ) |

Not residential | Independent | Alpha Epsilon Delta is a premedical honor society. The university's chapter is Virginia Gamma. | [129] | |

| Alpha Omega Alpha

(ΑΩΑ) |

Not residential | November 15, 1919 | Independent | Alpha Omega Alpha is an honorary medical society. The Alpha Virginia chapter was founded at UVA in 1919. | [130][131] |

| Alpha Sigma Lambda

(ΑΣΛ) |

Not residential | Independent | Alpha Sigma Lambda is an honor society that recognizes non-traditional students, such as adults with professional careers who are attending college. The UVA chapter is Beta Iota Sigma. | [132] | |

| Arnold Air Society | Not residential | Independent | The Arnold Air Society is an honor society open to students who participate in the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps. The UVA unit is the Demas T. Craw Squadron. | [133] | |

| Beta Gamma Sigma

(ΒΓΣ) |

Not residential | April 12, 1929 | Independent | Beta Gamma Sigma is an honorary commerce society. The university's chapter was established in 1929. | [134][135] |

| Chi Epsilon

(ΧΕ) |

Not residential | 1977 | Independent | Chi Epsilon is a civil engineering honor society. | [136][137] |

| Daniel Hale Williams Pre-Medical Honor Society | Not residential | Independent | The Daniel Hale Williams Pre-Medical Honor Society works to increase the number of ethnic minority physicians. | [138] | |

| Kappa Kappa Psi

(ΚΚΨ) |

Not residential | September 23, 1950 | Independent | Kappa Kappa Psi is a coeducational honorary band fraternity. It disbanded after the university's marching band shut down. After the Virginia Pep Band was banned from athletic events and replaced with the Cavalier Marching Band in 2004, the chapter was re-founded as the Beta Chi chapter. | [139][140] |

| National Society of Collegiate Scholars | Not residential | 1995 | Independent | The National Society of Collegiate Scholars is an academic honor society. | [141] |

| Nu Rho Psi

(ΝΡΨ) |

Not residential | Independent | Nu Rho Psi is a national honor society for neuroscience students. | [142] | |

| Omega Chi Epsilon

(ΩΧΕ) |

Not residential | 2010 | Independent | Omega Chi Epsilon is a chemical engineering honor society. The UVA chapter is Gamma Gamma. | [143] |

| Order of Omega

(Ω) |

Not residential | October 11, 1989 | Independent | The Order of Omega is a Greek society that seeks to recognize leaders in the fraternity and sorority community. The UVA chapter is Kappa Zeta. | [144] |

| Phi Beta Kappa

(ΦΒΚ) |

Not residential | June 16, 1908 | Independent | Phi Beta Kappa is a coed honor society. The UVA chapter is Beta of Virginia and was established in 1908. | [25][145] |

| Phi Eta Sigma

(ΦΕΣ) |

Not residential | March 4, 1990 | Independent | Phi Eta Sigma is an honor society that recognizes academically successful freshmen. | [146] |

| Phi Sigma Pi

(ΦΣΠ) |

Not residential | March 3, 1991 | Independent | Phi Sigma Pi, or "PSP," is a coed national honor society. The UVA chapter is Alpha Omicron. | [147] |

| Pi Tau Sigma

(ΠΤΣ) |

Not residential | April 30, 1977 | Independent | Pi Tau Sigma established its Virginia Delta Xi chapter at UVA in 1977. It is a mechanical engineering honor society. | [148] |

| Raven Society | Not residential | April 27, 1904 | Independent | The Raven Society is a local, coed honor society that draws its membership from many of the university's departments and fields of study. | [149][150] |

| Sigma Alpha Lambda

(ΣΑΛ) |

Not residential | Independent | Sigma Alpha Lambda is a coeducational leadership honor society. | [151] | |

| Sigma Delta Pi

(ΣΔΠ) |

Not residential | May 12, 1967 | Independent | Sigma Delta Pi is a coeducational Spanish honor society. The UVA chapter is Zeta Zeta. | [152] |

| Sigma Theta Tau

(ΣΘΤ) |

Not residential | 1972 | Independent | Sigma Theta Tau is a national coed nursing honor society. The UVA chapter is designated Beta Kappa. | [153] |

| Tau Beta Pi

(ΤΒΠ) |

Not residential | May 28, 1921 | Independent | Tau Beta Pi is an engineering honor society and established its Virginia Alpha chapter at UVA in 1921. | [154][155] |

| Tau Beta Sigma

(ΤΒΣ) |

Not residential | April 13, 2008 | Independent | Tau Beta Sigma is an honorary band sorority. The UVA chapter is Iota Kappa. | [156][157] |

Defunct and inactive organizations

Several organizations have historically existed at the university, but are not currently active. Some of these chapters still have extant national organizations, but the University of Virginia chapter is inactive; others were local fraternities that are no longer in existence; still, others are no longer active because their entire national organization became extinct. They are listed below:

Fraternities

- Alpha Chi Rho (ΑΧΡ)[25]

- Dedils[11]

- Delta Chi (ΔΧ)[25][158]

- Delta Kappa (ΔΚ)[8]

- Delta Lambda Phi (ΔΛΦ)[48][159][160][161][162][163]

- Delta Sigma Rho (ΔΣΡ) (Honor Society - Forensics)[164]

- Delta Tau Delta (ΔΤΔ)[165]

- Eta Lodge[166]

- Iota Phi Theta (ΙΦΘ)[167]

- Kappa Delta Mu (ΚΔΜ)[25]

- Kappa Phi Lambda (ΚΦΛ)[168]

- Kappa Sigma Kappa (ΚΣΚ)[168]

- Lambda Pi (ΛΠ)[165]

- Mu Pi Lambda (ΜΠΛ)[165]

- Nu Sigma Nu (ΝΣΝ)[169]

- Omega Theta Pi (ΩΘΠ)[11]

- Phi Alpha Chi (ΦΑΧ)[170]

- Phi Beta Pi (ΦΒΠ)[171]

- Phi Delta Phi (ΦΔΦ)[165]

- Phi Epsilon Pi (ΦΕΠ)[25]

- Phi Kappa Alpha (ΦΚΑ)[172]

- Phi Kappa Sigma (ΦΚΣ)[165]

- Phi Rho Sigma (ΦΡΣ)[173]

- Phi Theta Psi (ΦΘΨ)[172]

- Pi Mu (ΠΜ)[165][174]

- Psi Theta Psi (ΨΘΨ)[175]

- Sigma Alpha (ΣΑ)[175]

- Sigma Phi Epsilon (ΣΦΕ)[176]

- Skull & Keys[33]

- Theta Nu Epsilon (ΘΝΕ)[177]

Sororities

- Alpha Omicron Pi (ΑΟΠ)

- Alpha Xi Delta (ΑΞΔ)

- Phi Mu (ΦΜ)

- Sigma Gamma Rho (ΣΓΡ)

See also

- Rugby Road

- Secret societies at the University of Virginia

- History of the University of Virginia

- Fraternities and sororities in North America

- List of social fraternities and sororities

- Professional fraternities and sororities

- Service fraternities and sororities

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilson, Charles; Mohr, Clarence (2011). New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Education (17th ed.). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80-787201-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj "Fraternity and Sorority Life at the University of Virginia, 2014–2015" (PDF). University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "Map of Chapter Houses [Map]" (PDF). University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Lawn Application: Application FAQs". University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Patton, John (1906). Jefferson, Cabell, and the University of Virginia. New York: Neale Publishing Company. pp. 234–253. ISBN 978-1-29-044999-1.

edgar mason.

- ^ a b c d e f g "History of Fraternity and Sorority Life". University of Virginia Office of The Dean of Students. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ Bruce, Philip (1921). History of the University of Virginia: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man. Vol. III. New York: Macmillan. p. 167. OCLC 4622980.

- ^ a b Giambrone, Jeff (2012). Images of America: Remembering Mississippi's Confederates. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-73-859413-2.

- ^ a b c d Bruce, Philip (1921). History of the University of Virginia, 1819–1919: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man. Vol. IV. New York: Macmillan. pp. 94–101. OCLC 4622980.

- ^ Geiger, Roger (2015). The History of American Higher Education: Learning and Culture from the Founding to WWII. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-69-114939-4.

- ^ "Founding History". PIKE: Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "A History of Beta". Pi Kappa Alpha: Beta chapter, Davidson College. Beta chapter, Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Expansion". PIKE: Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Baird, William Raimond (1920). Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities (9th ed.). New York: James T. Brown. p. 306. OCLC 17350924.

- ^ "A Crucial Turning Point". PIKE: Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Garnet & Gold Pledge Guide (15th ed.). Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. 1970. OCLC 9396988.

- ^ Hughey, Matthew W (2006). "Black, White, Greek...Like Who?: Howard University Student Perceptions of a White Fraternity on Campus" (PDF). Educational Foundations. 20 (1–2): 14–15. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c Baird, William Raimond (1920). Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities (9th ed.). New York: James T. Brown. p. 219. OCLC 17350924.

- ^ Patterson, Homer L. (1913). Patterson's American Educational Directory, Vol IX. New York, NY: American Educational Company. p. 597.

- ^ "Champion Quest". Kappa Sigma Fraternity. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "National History". Kappa Sigma - Beta Eta chapter. Kappa Sigma at Auburn University. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Our Greatest Biennium in History". The Order. Kappa Sigma Fraternity. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bruce, Philip (1921). History of the University of Virginia, 1819–1919: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man. Vol. 5. New York: Macmillan. pp. 271–287. OCLC 4622980.

- ^ "Dawson's Row". Student Housing at the University of Virginia. University of Virginia School of Architecture. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Boarding Houses". Student Housing at the University of Virginia. University of Virginia School of Architecture. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Greek Houses". Student Housing at the University of Virginia. University of Virginia School of Architecture. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Greek Houses: Frat List". Student Housing at the University of Virginia. University of Virginia School of Architecture. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ Lay, Edward K. (2000). The Architecture of Jefferson Country: Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia. Charlottesville, Virginia: The University Press of Virginia. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-81-391885-3.

- ^ "1920–1947: Troubled Peace and Another War". Zeta Psi Fraternity. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "History of Trigon Engineering Society". Trigon Engineering Society. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "History of the Virginia ISC". Virginia's Inter-Sorority Council. University of Virginia Inter-Sorority Council. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. pp. 477–486. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ a b c d Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. pp. 275–282. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ "Historic Renovation Corporation". University of Virginia Foundation. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. pp. 477–479. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ a b c d "1982: The Rise and Fall of Easters". Virginia Magazine. U.Va. Alumni Association. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Chapters of the Multicultural Greek Council". University of Virginia Multicultural Greek Council. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Jenn (November 14, 2002). "IFC decides to admit local fraternities". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Roberts, Jenn (October 11, 2002). "Phi Delta Alpha name changes to Phi Society". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c "About Phi Society". Phi Society & Pre-2000 Phi Delta Theta. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Isaacs, Ann-Woods (November 14, 2001). "New Phi Delt signs lease for dry house". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Eanes, Kayla (October 13, 2015). "Gender-inclusive fraternity joins Multicultural Greek Council". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Meyers, Kathleen (March 25, 2004). "MGC votes to sponsor gay student fraternity". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Standards". University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. July 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Fraternal Organization Agreement (2015-2016)" (PDF). University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Commonly Asked Questions". Virginia's Inter-Sorority Council. University of Virginia Inter-Sorority Council. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "Inter-Fraternity Council". University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "History of the NPHC". University of Virginia National Pan-Hellenic Council. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". University of Virginia Multicultural Greek Council. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "University of Virginia's Corks & Curls 2001 - Jewish Greek Council Page". June 9, 2001 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Erdely, Sabrina (November 19, 2014). "A Rape on Campus: A Brutal Assault and Struggle for Justice at UVA". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ "Phi Kappa Psi Reinstated at the University of Virginia". UVA Today. January 12, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Jacobs, Peter (January 12, 2015). "Police Investigation Clears UVA Phi Psi Fraternity". Business Insider. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Schow, Ashe (January 30, 2015). "U.Va. President Admits Rape Story Was False; Keeps Restrictions on Fraternities". Washington Examiner. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Robinson, Owen; Stolberg, Sheryl (March 23, 2015). "Police Find No Evidence of Rape at UVA Fraternity". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Somaiya, Ravi (April 5, 2015). "Rolling Stone Retracts Article on Rape at University of Virginia". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "UVA lawsuit raises the question of what counts as hazing". Higher Ed Dive. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Sorority charged with 'hazing' for requiring members to study 25 hours per week". The College Fix. January 6, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Sigma Lambda Upsilon v. Rector of Univ. of Va., 503 F. Supp. 3d 433 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Lawsuit: Sorority Guilty of 'Hazing' for Requiring Members to Study 25 Hours per Week". National Review. January 8, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "What Constitutes Hazing". The Washington Post. February 2, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "UVA tells Latina sorority studying 25 hours a week is hazing, lawsuit says". NBC News. January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Hazing Schmazing". Kerry Dougherty. January 8, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Sorority suit: UVa said studying 25 hours a week is hazing". Associated Press. January 4, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "The Virginia Chapter". Alpha Delta Phi. Alpha Delta Phi Fraternity. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Alpha Delta Phi". The IFC at UVA. University of Virginia Inter-Fraternity Council. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "About Mu chapter". Alpha Epsilon Pi: Mu chapter. Mu chapter, Alpha Epsilon Pi. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "ΑΕΠ – Alpha Epsilon Pi". The IFC at UVA. University of Virginia Inter-Fraternity Council. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. (Iota Beta Chapter). Campus Labs. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Zeta Upsilon Chartered". Alpha Sigma Phi. Alpha Sigma Phi Fraternity. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Catalogue of the Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity: 1865-1897 (1897 ed.). Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity. 1897. p. 26. OCLC 669389769.

- ^ Denton-Edmundson, Matt (April 22, 2009). "Beta Theta Pi plans to return to Rugby Road". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "History". Chi Phi Fraternity, University of Virginia Alpha chapter. University of Virginia Alumni Association. May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Fraternity and Sorority Life at the University of Virginia, 2015-2016" (PDF). University of Virginia Fraternity and Sorority Life. University of Virginia Office of the Dean of Students. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Sloan, Teri (August 5, 2015). "174th annual convention in review". Chi Psi Fraternity. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Kappa chapter History". Delphic of Gamma Sigma Tau Fraternity, Inc. Kappa chapter, Delphic of Gamma Sigma Tau Fraternity. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "Delta Kappa Epsilon". The IFC at UVA. University of Virginia Inter-Fraternity Council. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "About DKE". Delta Kappa Epsilon, The University of Virginia's First Fraternity. University of Virginia Alumni Association. October 26, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "chapter Locator". Delta Sigma Phi Fraternity. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "History of Delta Upsilon". Delta Upsilon Fraternity, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Archived from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "History of Kappa Alpha Order". Kappa Alpha Order, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "Chapter History". Eta Sigma Nupes. Eta Sigma Chapter, Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "History of the Chapter". Kappa Sigma, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". University of Virginia Lambda Phi Epsilon. Lambda Phi Epsilon Fraternity. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "Membership". Lambda Phi Epsilon. Lambda Phi Epsilon Fraternity. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "chapter History". The Zeta Eta chapter of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. Zeta Eta chapter, Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ "Phi Gamma Delta". www.phigam.org.

- ^ Uberti, David (December 22, 2014). "The worst journalism of 2014". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Chipowsky, Margaret (November 8, 2000). "Phi Delta Alpha joins MGC fraternities". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "IFC Chapters". The IFC at UVA. University of Virginia Inter-Fraternity Council. April 4, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ "The History of Pi Kappa Alpha at the University". Pi Kappa Alpha, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "UVA Reorganization Underway". Pi Lambda Phi. Pi Lambda Phi Fraternity. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Pi Lambda Phi, Virginia Omega Alpha". UVA Pi Lam Alumni. Omega Alpha chapter, Pi Lambda Phi Fraternity. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "The History of Virginia Omicron". Sigma Alpha Epsilon, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. October 4, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "About Beta Psi". Sigma Alpha Mu, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. October 31, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "About Psi chapter". Sigma Chi Fraternity, University of Virginia. Psi chapter, Sigma Chi Fraternity. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "History". Sigma Phi Society at The University of Virginia. Alpha of Virginia chapter, Sigma Phi Society. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "The History of St. Anthony Hall at the University". St. Anthony Hall, University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "History". The St. Elmo Club of the University of Virginia. University of Virginia Alumni Association. February 6, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Ayres, B. Drummond Jr. (March 23, 1991). "11 Held and 3 Fraternities Seized In Drug Raids at U. of Virginia". New York Times.

- ^ "Gamma-Omicron". Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Xi Chapter Information". Theta Chi Fraternity, University of Virginia Xi Chapter. University of Virginia Alumni Association. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Pierson, Israel Coriell (1900). Zeta Psi Fraternity of North America, Founded June 1 Anno Domini 1847: Semicentennial Biographical Catalogue With Data to December 31, 1899. New York: Press of John C. Rankin Company. p. 655. OCLC 697872086.

- ^ "- @UVA".

- ^ "Chapter History". alpha Kappa Delta Phi Sorority, Inc., University of Virginia Sigma Chapter. Sigma Chapter, alpha Kappa Delta Phi Sorority. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "The House". Delta Gamma Fraternity, University of Virginia Epsilon Gamma. Group Interactive Networks. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Kappa Rho". The Kappa Rho Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Kappa Rho Chapter, Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Chapter History". Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. Gamma Alpha Chapter. Gamma Alpha Chapter, Lambda Theta Alpha Sorority. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Chapter History". Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. Iota Chapter. Iota Chapter, Omega Phi Beta Sorority. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Altamirano, Natasha (May 17, 2003). "Greek life over the years". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Our Chapter History". Pi Beta Phi at the University of Virginia. Pi Beta Phi Fraternity. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Lambda Chapter". Sigma Psi Zeta, Lambda Chapter. Lambda Chapter, Sigma Psi Zeta Sorority. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Cook, Hunter (September 3, 2009). "Students launch co-ed LGBT fraternity interest group". The Cavalier Daily. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "About Us".

- ^ Baird, William Raimond (1920). Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities (9th ed.). New York: James T. Brown. pp. 485, 600. ISBN 978-0-81-391213-4.

- ^ Corks and Curls. 1964. p. 132.

- ^ "The Chrome and Blue of Alpha Chi Sigma". 45 (2). October 2013: 2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "University of Virginia, Alpha Gamma Chapter". Alpha Kappa Psi Fraternity. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ "Pi Chapter History". Alpha Omega Epsilon at UVA. Pi Chapter, Alpha Omega Epsilon Sorority. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Corks and Curls. 1937. p. 248.

- ^ "Profile". Accounting Society at McIntire. Campus Labs. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Active Chapters". Beta Alpha Psi. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Accounting Society at McIntire". University of Virginia McIntire School of Commerce. University of Virginia. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Chapter List". Alpha Epsilon Delta. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Department of Medicine". University of Virginia Undergraduate Record. New Series. 7 (1). University of Virginia. December 1, 1920. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Chapter Directory". Alpha Sigma Lambda. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "Home". Arnold Air Society - Demas T. Craw Squadron. Campus Labs. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Chapter List". Beta Gamma Sigma. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ Corks and Curls. 1955. p. 272.

- ^ "Chapters by District". Chi Epsilon: The Civil Engineering Honor Society. Chi Epsilon. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "The Constitution and Bylaws of Chi Epsilon" (PDF). Chi Epsilon. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". Daniel Hale Williams Premedical Honor Society. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Chapter Listing". Kappa Kappa Psi. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Beta Chi History". Kappa Kappa Psi at the University of Virginia. Beta Chi Chapter, Kappa Kappa Psi Fraternity. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "University of Virginia". The National Society of Collegiate Scholars. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Chapters". Nu Rho Psi. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ "Chapter List". Omega Chi Epsilon: The National Honor Society for Chemical Engineering. Omega Chi Epsilon. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "Chapter Directory". Order of Omega. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ Voorhees, Oscar, ed. (May 1919). "The University of Virginia: Beta of Virginia". The Phi Beta Kappa Key. III. Somerville, NJ: Press of the Unionist-Gazette Association: 344. Retrieved July 31, 2015.