Tuareg people

Imuhăɣ/Imašăɣăn/Imajăɣăn ⵎⵂⵗ/ⵎⵛⵗⵏ/ⵎⵊⵗⵏ | |

|---|---|

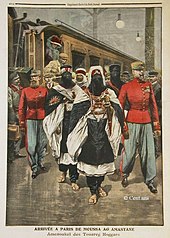

A Tuareg in Algiers, Algeria. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 4.0 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,793,652 (11% of its total population)[1] | |

| 704,814 (1.7% of its total population)[2] | |

| 406,271 (1.9% of its total population)[3] | |

| 100,000–250,000 (nomadic, 1.5% of its total population)[4][5] | |

| 152,000 (0.34% of its total population)[6][7] | |

| 123,000 (2.6% of its total population)[8] | |

| 30,000 (0.015% of its total population)[9] | |

| Languages | |

| Tuareg languages (Tamahaq, Tamasheq/Tafaghist, Tamajeq, Tawellemmet), Maghrebi Arabic, French (those resident in Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso), Hassaniya Arabic (those residing in Mauritania, Mali, and Niger), English (those resident in Nigeria), Algerian Saharan Arabic (those residing in Algeria and Niger) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Berbers, Arab-Berbers and Arabized Berbers, Songhay people, Hausa people | |

The Tuareg people (/ˈtwɑːrɛɡ/; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn[10]) are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Algeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and as far as northern Nigeria.[11][12]

The Tuareg speak languages of the same name, also known as Tamasheq, which belong to the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic family.[13]

They are a semi-nomadic people who mostly practice Islam, and are descended from the indigenous Berber communities of Northern Africa, whose ancestry has been described as a mosaic of local Northern African (Taforalt), Middle Eastern, European (Early European Farmers), and Sub-Saharan African, prior to the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb.[14][15] Some researchers have tied the origin of the Tuareg ethnicity with the fall of the Garamantes who inhabited the Fezzan (Libya) from the 1st millennium BC to the 5th century AD.[16][17] Tuareg people are credited with spreading Islam in North Africa and the adjacent Sahel region.[18]

Tuareg social structure has traditionally included clan membership, social status and caste hierarchies within each political confederation.[19][20][21] The Tuareg have controlled several trans-Saharan trade routes and have been an important party to the conflicts in the Saharan region during the colonial and post-colonial eras.[19]

Names

The origins and meanings of the name Tuareg have long been debated. It would appear that Twārəg is derived from the broken plural of Tārgi, a name whose former meaning was "inhabitant of Targa", the Tuareg name of the Libyan region commonly known as Fezzan. Targa in Berber means "(drainage) channel".[22] Another theory is that Tuareg is derived from Tuwariq, the plural of the Arabic exonym Tariqi.[11]

The term for a Tuareg man is Amajagh (variants: Amashegh, Amahagh), the term for a woman Tamajaq (variants: Tamasheq, Tamahaq, Timajaghen). Spellings of the appellation vary by Tuareg dialect. They all reflect the same linguistic root, expressing the notion of "freemen". As such, the endonym strictly refers only to the Tuareg nobility, not the artisanal client castes and the slaves.[23] Two other Tuareg self-designations are Kel Tamasheq, meaning "speakers of Tamasheq", and Kel Tagelmust, meaning "veiled people" in allusion to the tagelmust garment that is traditionally worn by Tuareg men.[11]

The English exonym "Blue People" is similarly derived from the indigo color of the tagelmust veils and other clothing, which sometimes stains the skin underneath giving it a blueish tint.[24] Another term for the Tuareg is Imuhagh or Imushagh, a cognate to the northern Berber self-name Imazighen.[25]

Demography and languages

The Tuareg today inhabit a vast area in the Sahara, stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Algeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and the far north of Nigeria.[11] Their combined population in these territories exceeds 2.5 million, with an estimated population in Niger of around 2 million (11% of inhabitants) and in Mali of another 0.5 million (3% of inhabitants).[1][26]

The Tuareg are the majority ethnic group in the Kidal Region of northeastern Mali.[27]

The Tuareg traditionally speak the Tuareg languages, also known as Tamasheq, Tamajeq or Tamahaq, depending on the dialect.[28] These languages belong to the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic family.[13] According to Ethnologue, there are an estimated 1.2 million Tuareg speakers. Around half of this number consists of speakers of the eastern dialect (Tamajaq, Tawallammat).[13]

The exact number of Tuareg speakers per territory is uncertain. The CIA estimates that the Tuareg population in Mali constitutes approximately 0.9% of the national population (~150,000), whereas about 3.5% of local inhabitants speak Tuareg (Tamasheq) as a primary language.[29] In contrast, Imperato (2008) estimates that the Tuareg represent around 3% of Mali's population.[26]

History

Early history

In antiquity, the Tuareg moved southward from the Tafilalt region into the Sahel under the Tuareg founding queen Tin Hinan, who is believed to have lived between the 4th and 5th centuries.[30] The matriarch's 1,500-year-old monumental Tin Hinan tomb is located in the Sahara at Abalessa in the Hoggar Mountains of southern Algeria. Vestiges of an inscription in Tifinagh, the Tuareg's traditional Libyco-Berber writing script, have been found on one of the ancient sepulchre's walls.[31]

External accounts of interactions with the Tuareg are available from at least the 10th century onwards. Ibn Hawkal (10th century), El-Bekri (11th century), Edrisi (12th century), Ibn Battutah (14th century), and Leo Africanus (16th century) all documented the Tuareg in some form, usually as Mulatthamin or "the veiled ones". Of the early historians, fourteenth century scholar Ibn Khaldûn probably wrote some of the most detailed commentary on the life and people of the Sahara, though he apparently never actually met them.[32]

Colonial era

At the turn of the 19th century, the Tuareg territory was organised into confederations, each ruled by a supreme Chief (Amenokal), along with a council of elders from each tribe. These confederations were sometimes called "Drum Groups" after the Amenokal's symbol of authority, a drum. Clan (Tewsit) elders, called Imegharan (wisemen), were chosen to assist the chief of the confederation. Historically, there have been seven major confederations.[33]

- Kel Ajjer or Azjar: centred in the oasis of Aghat (Ghat).

- Kel Ahaggar, in Ahaggar mountains.

- Kel Adagh, or Kel Assuk: Kidal and Timbuktu

- Iwillimmidan Kel Ataram or Western Iwillimmidan: Ménaka and Azawagh regions (Mali)

- Iwillimmidan Kel Denneg, or Eastern Iwillimmidan: Tchin-Tabaraden, Abalagh, Teliya Azawagh (Niger).

- Kel Ayr: Assodé, Agadez, In Gal, Timia and Ifrwan.

- Kel Gres: Zinder and Tanut (Tanout) and south into northern Nigeria.

- Kel Owey: Aïr Massif, seasonally south to Tessaoua (Niger)

In the mid-19th century, descriptions of the Tuareg and their way of life were made by the English traveller James Richardson in his journeys across the Libyan Sahara in 1845–1846.[34] In the late 19th century, the Tuareg resisted the French colonial invasion of their central Saharan homelands and annihilated a French expedition led by Paul Flatters in 1881. Over decades of fighting, Tuareg broadswords were no match for the firearms of French troops.[35]

After numerous massacres on both sides,[36] the Tuareg were defeated and forced to sign treaties in Mali in 1905 and Niger in 1917. In southern Algeria, the French met some of the strongest resistance from the Ahaggar Tuareg. Their Amenokal chief Moussa ag Amastan fought numerous battles, but eventually Tuareg territories were subdued under French governance.

French colonial administration of the Tuareg was largely based on supporting the existing social hierarchy. The French concluded that Tuareg rebellions were largely the result of reform policies that undermined the traditional chiefs. The colonial authorities wished to create a protectorate operating, ideally, through single chieftains who ruled under French sovereignty, but were autonomous within their territories. Thus French rule, relying on the loyalty of the Tuareg noble caste, did not improve the status of the slave class.[37]

Post-colonial era

When African countries achieved widespread independence in the 1960s, the traditional Tuareg territory was divided among a number of modern states: Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso. Political instability and competition for resources in the Sahel has since led to conflicts between the Tuareg and neighboring African groups. There have been tight restrictions placed on nomadic life because of high population growth. Desertification is exacerbated by over-exploitation of resources including firewood. This has pushed some Tuareg to experiment with farming; some have been forced to abandon herding and seek jobs in towns and cities.[38]

Following the independence of Mali, a Tuareg uprising broke out in the Adrar N'Fughas mountains in the 1960s, joined by Tuareg groups from the Adrar des Iforas in northeastern Mali. The Malian Army suppressed the revolt, but resentment among the Tuareg fueled further uprisings.[38]

This second (or third) uprising was in May 1990. In the aftermath of a clash between government soldiers and Tuareg outside a prison in Tchin-Tabaraden, Niger, Tuareg in both Mali and Niger claimed independence for their traditional homeland: Ténéré in Niger, including their capital Agadez, and the Azawad and Kidal regions of Mali.[39]

Deadly clashes between Tuareg fighters, with leaders such as Mano Dayak, and the military of both countries followed, with deaths into the thousands. Negotiations initiated by France and Algeria led to peace agreements in January 1992 in Mali and in 1995 in Niger, both arranging for decentralization of national power and the integration of Tuareg resistance fighters into the countries' national armies.[40]

Major fighting between the Tuareg resistance and government security forces ended after the 1995 and 1996 agreements. As of 2004, sporadic fighting continued in Niger between government forces and Tuareg rebels. In 2007, a new surge in violence occurred.[41]

The development of Berberism in North Africa in the 1990s fostered a Tuareg ethnic revival.[42]

Since 1998, three different flags have been designed to represent the Tuareg.[43] In Niger, the Tuareg people remain socially and economically marginalized, remaining poor and unrepresented in Niger's central government.[44]

On 21 March 2021, IS-GS militants attacked several villages around Tillia, Niger, killing 141 people. The main victims of the massacres were the Tuaregs.[45]

Religion

The Tuareg traditionally adhered to the Berber mythology. Archaeological excavations of prehistoric tombs in the Maghreb have yielded skeletal remains that were painted with ochre. Although this ritual practice was known to the Iberomaurusians, the custom seems instead to have been primarily derived from the ensuing Capsian culture.[46] Megalithic tombs, such as the jedar sepulchres, were erected for religious and funerary practices. In 1926, one such tomb was discovered south of Casablanca. The monument was engraved with funerary inscriptions in the ancient Libyco-Berber writing script known as Tifinagh, which the Tuareg still use.[47]

During the medieval period, the Tuareg adopted Islam after its arrival with the Umayyad Caliphate in the 7th century.[18] In the 16th century, under the tutelage of El Maghili,[48] the Tuareg embraced the Maliki school of Sunni Islam, which they now primarily follow.[49] The Tuareg helped spread Islam further into the Western Sudan.[50] While Islam is the religion of the contemporary Tuareg, historical documents suggest that they initially resisted Islamization efforts in their traditional strongholds.[51][52]

According to the anthropologist Susan Rasmussen, after the Tuareg had adopted the religion, they were reputedly lax in their prayers and observances of other Muslim precepts. Some of their ancient beliefs still exist today subtly within their culture and tradition, such as elements of pre-Islamic cosmology and rituals, particularly among Tuareg women, or the widespread "cult of the dead", which is a form of ancestor veneration. For example, Tuareg religious ceremonies contain allusions to matrilineal spirits, as well as to fertility, menstruation, the earth and ancestresses.[14] Norris (1976) suggests that this apparent syncretism may stem from the influence of Sufi Muslim preachers on the Tuareg.[18]

The Tuaregs have been one of the influential ethnic groups in the spread of Islam and its legacy in North Africa and adjacent Sahel.[18] Timbuktu, an important Islamic center famed for its ulama, was established by Imasheghen Tuareg at the start of the 12th century.[53] It flourished under the protection and rule of a Tuareg confederation.[54][55] However, modern scholars believe that there is insufficient evidence to pinpoint the exact time of origin and founders of Timbuktu, although it is archeologically clear that the city originated from local trade between the Middle Niger Delta, on the one hand, and between the pastoralists of the Sahara, long before the first hijra.[56] Monroe asserts, based on archaeological evidence, that Timbuktu emerged from an urban-rural dynamic, that is, aiming to provide services to its immediate rural hinterland.[57]

In 1449, a Tuareg ruling house founded the Tenere Sultanate of Aïr (Sultanate of Agadez) in the city of Agadez in the Aïr Mountains.[25]

18th century Tuareg Islamic scholars such as Jibril ibn 'Umar later preached the value of revolutionary jihad. Inspired by these teachings, Ibn 'Umar's student Usman dan Fodio led the Sokoto jihads and established the Sokoto Caliphate.[58]

Society

Tuareg society has traditionally featured clan membership, social status and caste hierarchies within each political confederation.[19]

Clans

Clans have been a historic part of the Tuaregs. The 7th century invasion of North Africa from the Middle East triggered an extensive migration of Tuaregs such as the Lemta and the Zarawa, along with other fellow pastoral Berbers.[14] Further invasions of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym Arab tribes into Tuareg regions in the 11th century moved the Tuareg south into seven clans, which the oral tradition of Tuaregs claims are descendants of the same mother.[14][59]

Each Tuareg clan (tawshet) is made up of family groups constituting a tribe,[20] each led by its chief, the amghar. A series of tawsheten (plural of tawshet) may bond together under an Amenokal, forming a Kel clan confederation. Tuareg self-identification is related only to their specific Kel, which means "those of". For example, Kel Dinnig (those of the east), Kel Ataram (those of the west).[60]

The position of amghar is hereditary through a matrilineal principle; it is usual for the son of a sister of the incumbent chieftain to succeed to his position. The amenokal is elected in a ritual which differs between groups. The individual amghar who lead the clans making up the confederation usually have the deciding voice.[60] The matrilineal inheritance and mythology among Tuareg clans, states Susan Rasmussen, is a cultural vestige from the pre-Islamic era of the Tuareg society.[14]

According to Rasmussen, Tuareg society exhibits a blend of pre-Islamic and Islamic practices.[14] Patrilineal Muslim values are believed to have been superimposed upon the Tuareg's traditional matrilineal society. Other apparently newer customs include close-cousin endogamous marriages and polygyny in conformity with Islamic tenets. Polygyny, which has been witnessed among Tuareg chiefs and Islamic scholars, is in turn thought to have been contrary to the pre-Islamic monogamous tradition of the nomadic Tuareg.[14]

Social stratification

Tuareg society has featured caste hierarchies within each clan and political confederation.[19][20][21] These hierarchical systems have included nobles, clerics, craftsmen and unfree strata of people including widespread slavery.[61][62]

Nobility, vassals and clerics

Traditionally, Tuareg society is hierarchical, with nobility and vassals. The linguist Karl-Gottfried Prasse (1995) indicates that the nobles constitute the highest caste.[63] They are known in the Tuareg language as imušaɣ/imuhaɣ/imajăɣăn "the proud and free".[19]

The nobles originally had a monopoly on carrying arms and owning camels, and were the warriors of the Tuareg regions.[64] They may have achieved their social status by subjugating other Tuareg castes, keeping arms to defend their properties and vassals. They have collected tribute from their vassals. This warrior nobility has traditionally married within their caste, not to individuals in strata below their own.[64]

A collection of tribes, each led by a noble, forms a confederation whose chieftain, the amănokal, is elected from among the nobles by the tribal chiefs.[63][62] The chieftain is the overlord during times of war, and receives tribute and taxes from tribes as a sign of their submission to his authority.[65]

The vassal-herdsmen are the second free stratum within Tuareg society, occupying a position just below that of the nobles.[66] They are known as ímɣad (Imghad, singular Amghid) in the Tuareg language.[62] Although the vassals were free, they did not own camels but instead kept donkeys and herds of goats, sheep and oxen. They pastured and tended their own herds as well those owned by the nobles of the confederation.[66] The vassal strata have traditionally paid an annual tiwse, or tribute to the nobles as a part of their status obligations, and hosted any noble who was traveling through their territory.[67]

In the late Medieval era, states Prasse, the previously existing weapon monopoly of the nobility broke down after regional wars took a heavy toll on the noble warrior strata, and thereafter the vassals carried weapons as well and were recruited as warriors.[67] After the start of the French colonial rule, which deprived the nobles of their powers over war and taxation, the Tuaregs belonging to the noble strata disdained tending cattle and tilling the land, seeking instead soldiering or intellectual work.[67]

A semi-noble stratum of the Tuareg people has been the endogamous religious clerics, the marabouts (Tuareg: Ineslemen, a loan word that means Muslim in Arabic).[67] After the adoption of Islam, they became integral to the Tuareg social structure.[68] According to Norris (1976), this stratum of Muslim clerics has been a sacerdotal caste, which propagated Islam in North Africa and the Sahel between the 7th and 17th centuries.[18] Adherence to the faith was initially centered around this caste, but later spread to the wider Tuareg community.[69] The marabouts have traditionally been the judges (qadi) and religious leaders (imam) of a Tuareg community.[67]

Castes

According to anthropologist Jeffrey Heath, Tuareg artisans belong to separate endogamous castes known as the Inhăḍăn (Inadan).[62][70] These have included blacksmith, jeweler, wood worker and leather artisan castes.[62] They produced and repaired the saddles, tools, household items and other items for the Tuareg community. In Niger and Mali, where the largest Tuareg populations are found, the artisan castes were attached as clients to a family of nobles or vassals, carried messages over distances for their patron family, and traditionally sacrificed animals during Islamic festivals.[70]

These social strata, like caste systems found in many parts of West Africa, included singers, musicians and story tellers of the Tuareg, who kept their oral traditions.[71] They are called Agguta by Tuareg, have been called upon to sing during ceremonies such as weddings or funerals.[72] The origins of the artisanal castes are unclear. One theory posits a Jewish derivation, a proposal that Prasse calls "a much vexed question".[70] Their association with fire, iron and precious metals and their reputation for being cunning tradesmen has led others to treat them with a mix of admiration and distrust.[70]

According to Rasmussen, the Tuareg castes are not only hierarchical, as each caste differs in mutual perception, food and eating behaviors. For example, she relates an explanation by a smith on why there is endogamy among Tuareg castes in Niger. The smith explained, "nobles are like rice, smiths are like millet, slaves are like corn".[73]

The people who farm oases in some Tuareg-dominated areas form a distinct group known as izeggaghan (or hartani in Arabic). Their origins are unclear but they often speak both Tuareg dialects and Arabic, though a few communities are Songhay speakers.[74] Traditionally, these local peasants were subservient to the warrior nobles who owned the oasis and the land. The peasants tilled these fields, whose output they gave to the nobles after keeping a fifth part of the produce.[74] Their Tuareg patrons were usually responsible for supplying agricultural tools, seed and clothing. The peasants' origins are also unclear. One theory postulates that they are descendants of ancient people who lived in the Sahara before they were dominated by invading groups. In contemporary times, these peasant strata have blended in with freed slaves and farm arable lands together.[74]

Slaves

The Tuareg confederations acquired slaves, often of Nilotic origin,[76] as well as tribute-paying states in raids on surrounding communities.[19] They also took captives as war booty or purchased slaves in markets.[77] The slaves or servile communities are locally called Ikelan (or Iklan, Eklan), and slavery is inherited, with the descendants of the slaves known as irewelen.[19][70]

They often live in communities separate from other castes. The Ikelan's Nilotic extraction is denoted via the Ahaggar Berber word Ibenheren (sing. Ébenher).[78]

The word ikelan is the plural form of "slave",[79] an allusion to most of the slaves.[77] In post-colonial literature, the alternate terms for Ikelan include "Bellah-iklan" or just "Bellah", derived from a Songhay word.[75][80]

According to historian Priscilla Starratt (1981), the Tuareg evolved a system of slavery that was highly differentiated. They established strata among their slaves, which determined rules as to the slave's expected behavior, marriageability, inheritance rights if any, and occupation.[81] The Ikelan later became a bonded caste within Tuareg society, and they now speak the same Tamasheq language as Tuareg nobles and share many customs.[78] According to Heath, the Bella in Tuareg society were the slave caste whose occupation was rearing and herding livestock such as sheep and goats.[62]

French colonial governments stopped the acquisition of new slaves and slave trading in markets, but they did not remove or free domestic slaves from the Tuareg owners who had acquired them before French rule.[82][83] In Tuareg society, like many others in West Africa, slave status was inherited, and the upper strata used slave children for domestic work, at camps and as dowry gifts to newlyweds.[84][85][86]

According to Bernus (1972), Brusberg (1985) and Mortimore (1972), French colonial interests in the Tuareg region were primarily economic, and they had no intention of ending the slave-owning institution.[87] Historian Martin A. Klein (1998) says that although French colonial rule indeed did not end domestic slavery in Tuareg society, the French reportedly attempted to impress upon the nobles the equality of the Imrad[definition needed] and Bella and to encourage the slaves to claim their rights.[88]

He suggests that there was a large scale attempt by French West African authorities to liberate slaves and other bonded castes in Tuareg areas following the 1914–1916 Firouan revolt.[89] Despite this, French officials following the Second World War reported that there were some 50,000 Bella under direct control of Tuareg masters in the Gao–Timbuktu area of French Sudan alone.[90] This was at least four decades after French declarations of mass freedom in other areas of the colony.

In 1946, a series of mass desertions of Tuareg slaves and bonded communities began in Nioro and later in Ménaka, quickly spreading along the Niger River valley.[91] In the first decade of the 20th century, French administrators in southern Tuareg areas of the French Sudan estimated that "free" to "servile" groups within Tuareg society existed at ratios of 1 to 8 or 9.[92] At the same time, the servile rimaibe population of the Masina Fulbe, roughly equivalent to the Bella, constituted between 70% and 80% of the Fulbe population, while servile Songhay groups around Gao made up some 2/3 to 3/4 of the total Songhay population.[92] Klein concludes that approximately 50% of the population of French Sudan at the beginning of the 20th century was in some servile or slave relationship.[92]

While post-independence states have sought to outlaw slavery, results have been mixed. Certain Tuareg communities still uphold the institution.[93] Traditional caste relationships have continued in many places, including slaveholding.[94][95] In Niger, where the practice of slavery was outlawed in 2003, according to ABC News, almost 8% of the population are still enslaved.[96] The Washington Post reported that many slaves held by the Tuareg in Mali were liberated during 2013–14 when French troops intervened on behalf of the Malian government against Islamic radicals.[97][98]

Chronology

Tuareg social stratification into noble, clerical and artisanal castes likely emerged after the 10th century, as a corollary of the rising slavery system.[99] Similar caste institutions are found in other communities in Africa.[100] According to anthropologist Tal Tamari, linguistic evidence suggests that the Tuareg blacksmith and bard endogamous castes evolved under foreign contact with Sudanic peoples, since the Tuareg terms for "blacksmith" and "bard" are of non-Berber origin.[101] The designation for the endogamous blacksmiths among the southern Tuareg is gargassa, a cognate of the Songhay garaasa and Fulani garkasaa6e, whereas it is enaden among the northern Tuareg, meaning "the other".[102]

Archaeological work by Rod McIntosh and Susan Keech McIntosh indicates that long-distance trade and specialized economies existed in the Western Sudan at an early date. During the 9th and 10th centuries, Berbers and Arabs built upon these pre-existing trade routes and quickly developed trans-Saharan and sub-Saharan transport networks. Successive local Muslim kingdoms developed increasing sophistication in their martial capacity, slave raiding, holding and trading systems. Among these Islamic states were the Ghana Empire (11th century), the Mali Empire (13th and 14th centuries), and the Songhay Empire (16th century).[99] Slavery created a template for servile relationships, which developed into more complex castes and social stratification.[103]

Culture

Tuareg culture is largely matrilineal.[104][105][106] Other distinctive aspects of Tuareg culture include clothing, food, language, religion, arts, astronomy, nomadic architecture, traditional weapons, music, films, games, and economic activities.

Clothing

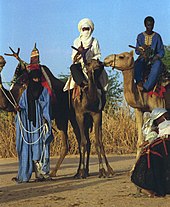

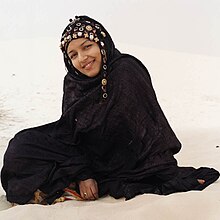

In Tuareg society women do not traditionally wear the face veil, whereas men do.[104][106] The most famous Tuareg symbol is the tagelmust (also called éghéwed and, in Arabic, litham), sometimes referred to as a cheche (pronounced "shesh"), a combined turban and veil, often indigo-blue colored. The men's facial covering originates from the belief that such action wards off evil spirits. It may have related instrumentally from the need for protection from the harsh desert sands as well.

It is a firmly established tradition, as is the wearing of amulets containing sacred objects and, recently, verses from the Qur'an. Taking on the veil is associated with the rite of passage to manhood. Men begin wearing a veil when they reach maturity. The veil usually conceals their face, excluding their eyes and the top of the nose.

Names for traditional clothing include:

- tagelmust: turban – men

- bukar: black cotton turban – men

- tasuwart: women's veil

- takatkat: shirt – women and men

- takarbast: short shirt – women and men

- akarbey: pants worn by men

- afetek: loose shirt worn by women

- afer: women's pagne

- tari: large black pagne for winter season

- bernuz: long woolen cloth for winter

- akhebay: loose bright green or blue cloth for women

- ighateman: shoes

- iragazan: red leather sandals

- ibuzagan: leather shoes

The traditional indigo turban is still preferred for celebrations, and generally Tuareg wear clothing and turbans in a variety of colors.

Food

Tagella is a flatbread made from wheat flour and cooked on a charcoal fire; the flat disk-shaped bread is buried under the hot sand. The bread is broken into small pieces and eaten with a meat sauce. Millet porridge called a cink or a liwa is a staple much like ugali and fufu. Millet is boiled with water to make a pap and eaten with milk or a heavy sauce. Common dairy foods are goat and camel milk, called akh, as well as a cheese, ta komart, and tona, a thick yogurt, made from them. Eghajira is a beverage drunk with a ladle, made by pounding millet, goat cheese, dates, milk, and sugar, served at festivals.

Just like in Morocco, the local popular tea, called atay or ashay, is made from gunpowder green tea with much sugar added. After steeping, it is poured three times in and out of the teapot over the tea, mint leaves and sugar and served by pouring from a height of over a foot into small tea glasses with a froth on top.

Language

The Tuareg natively speak the Tuareg languages. A dialect cluster, it belongs to the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic family.[107] Tuareg is known as Tamasheq by western Tuareg in Mali, as Tamahaq among Algerian and Libyan Tuareg, and as Tamajeq in the Azawagh and Aïr regions of Niger.

French missionary Charles de Foucauld compiled perhaps the earliest dictionary of the Tuareg language.[108] The Tuaregs compose a great deal of poetry, often elegiac, epigrammatic, and amatory. Charles de Foucauld, and other ethnographers have preserved thousands of these poems, many of which Foucauld translated into French.

Arts

As in other rural Berber traditions, jewellery made of silver, coloured glass or iron is a special artform of the Tuareg people.[109][110] While in other Berber cultures in the Maghreb jewelry is mainly worn by women, Tuareg men also wear necklaces, amulets and rings.

These traditional handicrafts are made by the inadan wan-tizol (makers of weapons and jewelry). Among their products are tanaghilt or zakkat (the 'Agadez Cross' or 'Croix d'Agadez'); the Tuareg sword (takoba), gold and silver necklaces called 'takaza' as well as earrings called 'tizabaten'. Pilgrimage boxes with intricate iron and brass decorations are used to carry items. Tahatint are made of goat skin.[111][112] Other such artifacts include metalwork for saddle decoration, called trik.

Most forms of the Agadez Cross are worn as pendants with varied shapes that either resemble a cross or have the shape of a plate or shield. Historically, the oldest known specimens were made of stone or copper, but subsequently Tuareg blacksmiths also used iron and silver, in the lost-wax casting technique. According to the article "The cross of Agadez" by Seligman and Loughran (2006), this piece has become a national and African symbol for Tuareg culture and political rights.[113] Today, these pieces of jewellery are often made for tourists or as items of ethnic-style fashion for customers in other countries, with certain modern changes.[114]

Astronomy

The clear desert skies allowed the Tuareg to be keen observers. Tuareg celestial objects include:

- Azzag Willi (Venus), which indicates the time for milking the goats

- Shet Ahad (Pleiades), the seven sisters of the night

- Amanar (Orion), the warrior of the desert

- Talemt (Ursa Major), the she-camel wakes up

- Awara (Ursa Minor), the baby camel goes to sleep

Nomadic architecture

While living quarters are progressively changing to adapt to a more sedentary lifestyle, Tuareg groups are well known for their nomadic architecture (tents). There are several documented styles, some covered with animal skin, some with mats. The style tends to vary by location or subgroup.[115] The tent is traditionally constructed for the first time during the marriage ceremony and is considered an extension of the union, to the extent that the phrase "making a tent" is a metaphor for becoming married.[116]

Because the tent is considered to be under the ownership of a married woman, sedentary dwellings generally belong to men, reflecting a patriarchal shift in power dynamics. Current documentation suggests a negotiation of common practice in which a woman's tent is set up in the courtyard of her husband's house.[117] It has been suggested that the traditional tent construction and arrangement of living space within it represent a microcosm of the greater world as an aide in the organization of lived experiences[116] so much so that movement away from the tent can cause changes in character for both men and women as its stabilizing force becomes faint.[118]

An old legend says the Tuareg once lived in grottoes, akazam, and they lived in foliage beds on the top acacia trees, tasagesaget. Other kinds of traditional housing include:[citation needed] ahaket (Tuareg goatskin red tent), tafala (a shade made of millet sticks), akarban also called takabart (temporary hut for winter), ategham (summer hut), taghazamt (adobe house for long stay), and ahaket (a dome-shaped house made of mats for the dry season and square shaped roof with holes to prevent hot air).[citation needed]

Traditional weapons

- takoba: 1 meter long straight sword

- sheru: long dagger

- telek: short dagger kept in a sheath attached to the left forearm.

- allagh: 2 meter long lance

- tagheda: small and sharp assegai

- taganze: leather covered-wooden bow

- amur: wooden arrow

- taburek: wooden stick

- alakkud or abartak: riding crop

- agher: 1.50 meter high shield

In 2007, Stanford's Cantor Arts Center opened an exhibition, "Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World", the first such exhibit in the United States. It was curated by Tom Seligman, director of the center. He had first spent time with the Tuareg in 1971 when he traveled through the Sahara after serving in the Peace Corps. The exhibition included crafted and adorned functional objects such as camel saddles, tents, bags, swords, amulets, cushions, dresses, earrings, spoons and drums.[119] The exhibition also was shown at the University of California, Los Angeles Fowler Museum in Angeles and the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C.

Throughout history, the Tuareg were renowned and respected warriors. Their decline as a military might came with the introduction of firearms, weapons which the Tuareg did not possess. The Tuareg warrior equipment consisted of a takoba (sword), allagh (lance), and aghar (shield) made of antelope hide.[citation needed]

Music

Traditional Tuareg music has two major components: the monochord violin anzad played often during night parties and a small tambour covered with goatskin called tende, performed during camel and horse races, and other festivities. Traditional songs called Asak and Tisiway (poems) are sung by women and men during feasts and social occasions. Another popular Tuareg musical genre is Takamba, characterized by its Afro percussions.

Vocal music

- tisiway: poems

- tasikisikit: songs performed by women, accompanied by tende (drum); the men, on camel-back, circle the women as they sing.

- asak: songs accompanied by anzad monocord violin.

- tahengemmit: slow songs sung by elder men

Children and youth music

- Bellulla: songs made by children playing with the lips

- Fadangama: small monocord instrument for children

- Odili flute: made from trunk of sorghum

- Gidga small: wooden instrument with irons sticks to make strident sounds

Dance

- Tagest: dance made while seated, moving the head, the hands and the shoulders

- Ewegh: strong dance performed by men, in couples and groups

- Agabas: dance for modern ishumar guitars: women and men in groups

In the 1980s rebel fighters founded Tinariwen, a Tuareg band that fuses electric guitars and indigenous musical styles. Especially in areas that were cut off during the Tuareg rebellion (e.g., Adrar des Iforas), they were practically the only music available, which helped them to regional success. They released their first CD in 2000, and toured in Europe and the United States in 2004. Tuareg guitar groups that followed in their path include Group Inerane and Group Bombino. The Niger-based band Etran Finatawa combines Tuareg and Wodaabe members, playing a combination of traditional instruments and electric guitars.

Music genres, groups and artists

Traditional music

- Majila Ag Khamed Ahmad: asak singer, from Aduk, Niger

- Almuntaha: anzad player, from Aduk

- Ajju: anzad player, from Agadez, Niger

- Islaman: asak singer, from Abalagh, Niger

- Tambatan: asak singer, from Tchin-Tabaraden, Niger

- Alghadawiat: anzad player, from Akoubounou, Niger

- Taghdu: anzad player, from Aduk

Ishumar music, also known as Teshumara or al guitarra music style

- Abdallah Oumbadougou, the "godfather" of the ishumar genre[120]

- In Tayaden, singer and guitar player, Adagh

- Abareybon, singer and guitar player in Tinariwen, Adagh

- Kiddu Ag Hossad, singer and guitar player, Adagh

- Baly Othmani singer, luth player, Djanet, Azjar

- Abdalla Ag Umbadugu, singer, Takrist N'Akal group, Ayr

- Hasso Ag Akotey, singer, Ayr

- Tinariwen, exemplar of the tishoumaren genre. Led Zeppelin's Robert Plant, a major supporter of Tinariwen and the Festival au Désert said of Tinariwen, "When I first heard them, I felt, this was the music I'd been looking for all my life."[121][122][123][124]

- Bombino, guitarist

- Kel Assouf

- Imarhan

- Les Filles de Illighadad, Niger

- Mdou Moctar, guitarist

Music and culture festivals

The Festival in the Desert in Mali's Timbuktu provides one opportunity to see Tuareg culture and dance and hear their music. Other festivals include:

- Cure Salee Festival in the oasis of In-Gall, Niger

- Sabeiba Festival in Ganat (Djanet), Algeria

- Shiriken Festival in Akabinu (Akoubounou), Niger

- Takubelt Tuareg Festival in Mali

- Ghat Festival in Aghat (Ghat), Libya

- Le Festival au Désert in Mali

- Ghadames Tuareg Festival in Libya

Films

- A Love Apart, was released in 2004 by Bettina Haasen.[126]

- Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai, was released in 2014 and stars the musician Mdou Moctar.[127][128][129][130]

- Zerzura is a Tamashek-language film released in 2017 by Sahel Sounds based on the Northern African fable of Zerzura[131]

Games

Tuareg traditional games and plays include:

- Tiddas, played with small stones and sticks.

- Kelmutan: consists of singing and touching each person's leg, where the ends, that person is out: the last person loses the game.

- Temse: comic game try to make the other team laugh and you win.

- Izagag, played with small stones or dried fruits.

- Iswa, played by picking up stones while throwing another stone.

- Melghas, children hide themselves and another tries to find and touch them before they reach the well and drink.

- Tabillant, traditional Tuareg wrestling

- Alamom, wrestling while running

- Solagh, another type of wrestling

- Tammazaga or Tammalagha, race on camel back

- Takket, singing and playing all night.

- Sellenduq one person to be a jackal and try to touch the others who escape running (tag).

- Takadant, children try to imagine what the others are thinking.

- Tabakoni: clown with a goatskin mask to amuse children.

- Abarad Iqquran: small dressed wooden puppet that tells stories and makes people laugh.

- Maja Gel Gel: one person tries to touch all people standing, to avoid this sit down.

- Bellus: everyone runs not to be touched by the one who plays (tag).

- Tamammalt: pass a burning stick, when it is blown off in one's hands tells who is the lover.

- Ideblan: game with girls, prepare food and go search for water and milk and fruits.

- Seqqetu: play with girls to learn how to build tents, look after babies made of clay.

- Mifa Mifa: beauty contest, girls and boys best dressed.

- Taghmart: children pass from house to house singing to get presents: dates, sugar, etc.

- Melan Melan: try to find a riddle

- Tawaya: play with the round fruit calotropis or a piece of cloth.

- Abanaban: try to find people while eyes are shut (blind man's bluff).

- Shishagheren, writing the name of one's lover to see if this person brings good luck.

- Taqqanen, telling devinettes and enigmas.

- Maru Maru, young people mime how the tribe works.

Economy

Tuareg are distinguished in their native language as the Imouhar, meaning the free people;[citation needed] the overlap of meaning has increased local cultural nationalism. Many Tuareg today are either settled agriculturalists or nomadic cattle breeders, while others are blacksmiths or caravan leaders. The Tuareg are a pastoral people, having an economy based on livestock breeding, trading, and agriculture.[132]

Caravan trade

Since prehistoric times, Tuareg peoples have been organising caravans for trading across the Sahara desert. The caravan in Niger from around Agadez to Fachi and Bilma is called Tarakaft or Taghlamt in Tamashek, and that in Mali from Timbuktu to Taoudenni, Azalay.[citation needed] These caravans used first oxen, horses and later camels as a means of transportation.

Salt mines or salines in the desert.

- Tin Garaban near Ghat in Azjar, Libya

- Amadghor in Ahaggar, Algeria

- Taoudenni in far northern Mali

- Tagidda N Tesemt in Azawagh, Niger

- Fachi in Ténéré desert, Niger

- Bilma in Kawar, eastern Niger

A contemporary variant is occurring in northern Niger, in a traditionally Tuareg territory that comprises most of the uranium-rich land of the country. The central government in Niamey has shown itself unwilling to cede control of the highly profitable mining to indigenous clans.[citation needed] The Tuareg are determined not to relinquish the prospect of substantial economic benefit. The French government has independently tried to defend a French firm, Areva, established in Niger for fifty years and now mining the massive uranium deposit.[133]

Additional complaints against Areva are that it is: "...plundering...the natural resources and [draining] the fossil deposits. It is undoubtedly an ecological catastrophe".[134] These mines yield uranium ores, which are then processed to produce yellowcake, crucial to the nuclear power industry, as well as aspirational nuclear powers. In 2007, some Tuareg people in Niger allied themselves with the Niger Movement for Justice (MNJ), a rebel group operating in the north of the country.

In 2004–2007, U.S. Special Forces teams trained Tuareg units of the Nigerien Army in the Sahel region as part of the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership. Some of these trainees are reported to have fought in the 2007 rebellion within the MNJ. The goal of these Tuareg appears to be economic and political control of ancestral lands, rather than operating from religious and political ideologies.[citation needed]

Despite the Sahara's erratic and unpredictable rainfall patterns, the Tuareg have managed to survive in the hostile desert environment for centuries. Over recent years however, depletion of water by the uranium exploitation process combined with the effects of climate change are threatening their ability to subsist. Uranium mining has diminished and degraded Tuareg grazing lands. The mining industry produces radioactive waste that can contaminate crucial sources of ground water resulting in cancer, stillbirths, and genetic defects, and uses up huge quantities of water in a region where water is already scarce.

This is exacerbated by the increased rate of desertification thought to be the result of global warming. Lack of water forces the Tuareg to compete with southern farming communities for scarce resources and this has led to tensions and clashes between these communities. The precise levels of environmental and social impact of the mining industry have proved difficult to monitor due to governmental obstruction.

Genetics

Y-chromosome DNA

Y-Dna haplogroups, passed on exclusively through the paternal line, were found at the following frequencies in Tuaregs:

| Population | Nb | A/B | E1b1a | E-M35 | E-M78 | E-M81 | E-M123 | F | K-M9 | G | I | J1 | J2 | R1a | R1b | Other | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuareg (Libya) | 47 | 0 | 43% | 0 | 0 | 49% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6% | 2% | Ottoni et al. (2011)[135] |

| Al Awaynat Tuareg (Libya) | 47 | 0 | 50% | 0 | 0 | 39% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8% | 3% | Ottoni et al. (2011)[135] |

| Tahala Tuareg (Libya) | 47 | 0 | 11% | 0 | 0 | 89% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ottoni et al. (2011)[135] |

| Tuareg (Mali) | 11 | 0 | 9.1% | 0 | 9.1% | 81.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011)[136] |

| Tuareg (Burkina Faso) | 18 | 0 | 16.7% | 0 | 0 | 77.8% | 0 | 0 | 5.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011) |

| Tuareg (Niger) | 18 | 5.6% | 44.4% | 0 | 5.6% | 11.1% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% | 0 | Pereira et al. (2011) |

E1b1b is the most common paternal haplogroup among the Tuareg. Most belong to its E1b1b1b (E-M81) subclade, which is colloquially referred to as the Berber marker due to its prevalence among Mozabite, Middle Atlas, Kabyle and other Berber groups. It reaches frequencies of up to 100 percent in some parts of the Maghreb, and is dominated by its sub-clade E-M183. M81 is thought to have originated in North Africa up to 14,000 years ago, but a single 2200-year-old branch M183-PF2546 dominates Northern and Eastern Berbers.[137] Its parent haplogroup E1b1b is associated with Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations, and is thought to have arisen in the Horn of Africa.[138][139]

Besides E1b1b, Pereira et al. (2011) and Ottoni et al. (2011) observed that certain Tuareg inhabiting Niger and Libya carry the E1b1a1-M2 haplogroup (see table above). This clade is today primarily found among Niger-Congo-speaking populations, which suggests that some Tuareg tribes in parts of Libya and Niger may have assimilated many persons of West African origin into their communities.[135][136] To wit, around 50% of individuals among the Al Awaynat Tuareg in Libya are E1b1a carriers compared to only 11% of the adjacent Tahala Tuareg. 89% of the Tahala belong instead to the E1b1b-M81 Berber founding lineage.[135]

mtDNA

According to mtDNA analysis by Ottoni et al. (2010) in a study of 47 individuals, the Tuareg inhabiting the Fezzan region in Libya predominantly carry the H1 haplogroup (61%). This is the highest global frequency found so far of the maternal clade. The haplogroup peaks among Berber populations. The remaining Libyan Tuareg mainly belong to two other West Eurasian mtDNA lineages, M1 and V.[140] M1 is today most common among other Afro-Asiatic speakers inhabiting East Africa, and is believed to have arrived on the continent along with the U6 haplogroup from the Near East around 40,000 years ago.[141] In 2009, based on 129 individuals, Libyan Tuareg were shown to have a maternal genetic pool with a "European" component similar to other Berbers, as well as a south Saharan contribution linked to Eastern Africa and Near Eastern populations.[142]

Pereira et al. (2010) in a study of 90 unrelated individuals observed greater matrilineal heterogeneity among the Tuareg inhabiting more southerly areas in the Sahel. The Tuareg in the Gossi environs in Mali largely bear the H1 haplogroup (52%), with the M1 lineage (19%), and various Sub-Saharan L2 subclades (19%) next most common. Similarly, most of the Tuareg inhabiting Gorom-Gorom in Burkina Faso carry the H1 haplogroup (24%), followed by various L2 subclades (24%), the V lineage (21%), and haplogroup M1 (18%).[141]

The Tuareg in the vicinity of Tanout in Maradi Region and westward to villages of Loube and Djibale in Tahoua Region in Niger are different from the other Tuareg populations in that a majority carry Sub-Saharan mtDNA lineages. In fact, the name for these mixed Tuareg-Haussa people is "Djibalawaa" named after the village of Djibale in Bouza Department, Tahoua Region of Niger. This points to significant assimilation of local West African females into this community. The most common maternal haplogroups found among the Tanout Tuareg are various L2 subclades (39%), followed by L3 (26%), various L1 sublineages (13%), V (10%), H1 (3%), M1 (3%), U3a (3%), and L0a1a (3%).[141]

Autosomal DNA

Based on classical genetic markers, according to Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A. (1994), the Tuareg have genetic affinities with the Beja people, a minority ethnic group inhabiting parts of Sudan, Egypt, and Eritrea. The inferred ethnogenesis of the Tuareg people happened within a time period of 9,000 to 3,000 years ago, and most likely took place somewhere in Northern Africa.[143][144][page needed]

A 2017 study by Arauna et al. which analyzed existing genetic data obtained from Northern African populations, such as Berbers, described them as a mosaic of local Northern African (Taforalt), Middle Eastern, European (Early European Farmers), and Sub-Saharan African-related ancestries.[145]

Notes

- ^ The 3000 year old Sebiba festival is celebrated each year in Djanet (Algeria) where inhabitants of Tassili n'Ajjer and Tuaregs from neighbouring countries meet to simulate through songs and dance the fights that once separated them.[125]

References

- ^ a b "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 8 October 2016., Niger: 11% of 23.6 million

- ^ "Africa: Mali – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021., Mali: 1.7% of 20.1 million

- ^ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 12 October 2021., Burkina Faso: 1.9% of 21.4 million

- ^ Adriana Petre; Ewan Gordon (7 June 2016). "Toubou-Tuareg Dynamics within Libya" (PDF). DANU Strategic Forecasting Group. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Tuareg and citizenship: 'The last camp of nomadism'". Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Project, Joshua. "Tuareg in Algeria". Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Project, Joshua. "Tahaggart Tuareg in Algeria". Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Tamasheq". Ethnologue. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Pongou, Roland (30 June 2010). "Nigeria: Multiple Forms of Mobility in Africa's Demographic Giant". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Anja Fischer / Imuhar (Tuareg) – designation". imuhar.eu. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Shoup III, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 295. ISBN 978-1598843637. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "The total Tuareg population is well above one million individuals." Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie, Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Elsevier, 2008, ISBN 9780080877747, p. 152.

- ^ a b c "Ethnologue: Languages of the World". Ethnologue.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rasmussen, Susan J. (1996). "Tuareg". In Levinson, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Culture, Volume 9: Africa and the Middle East. G.K. Hall. pp. 366–369. ISBN 978-0-8161-1808-3.

- ^ Arauna, Lara R; Comas, David (15 September 2017). "Genetic Heterogeneity between Berbers and Arabs". eLS: 1–7. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0027485. ISBN 9780470016176.

- ^ Wright, John (3 April 2007). The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-134-17987-9.

- ^ Ottoni, Claudio; Larmuseau, Maarten H. D.; Vanderheyden, Nancy; Martínez-Labarga, Cristina; Primativo, Giuseppina; Biondi, Gianfranco; Decorte, Ronny; Rickards, Olga (1 May 2011). "Deep into the roots of the Libyan Tuareg: a genetic survey of their paternal heritage". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 145 (1): 118–124. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21473. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 21312181.

- ^ a b c d e Harry T. Norris (1976). The Tuaregs: Their Islamic Legacy and Its Diffusion in the Sahel. London: Warminster. pp. 1–4, chapters 3, 4. ISBN 978-0-85668-362-6. OCLC 750606862.; For an abstract, ASC Leiden Catalogue; For a review of Norris' book: Stewart, C. C. (1977). "The Tuaregs: Their Islamic Legacy and its Diffusion in the Sahel. By H. T. Norris". Africa. 47 (4): 423–424. doi:10.2307/1158348. JSTOR 1158348. S2CID 140786332.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elizabeth Heath (2010). Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates (ed.). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 499–500. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- ^ a b c Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 16, 17–22, 38–44.

- ^ a b Tamari, Tal (1991). "The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa". The Journal of African History. 32 (2): 221–222, 228–250. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025718. S2CID 162509491.

- ^ Ghoubeid, Alojaly (2003). Dictionnaire touareg-français (in French). Museum Tusculanum. p. 656. ISBN 978-87-7289-844-5.

- ^ Hourst, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Gearon, Eamonn, (2011) The Sahara: A Cultural History Oxford University Press, p. 239

- ^ a b James B. Minahan (2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-61069-954-9.

- ^ a b Pascal James Imperato, Gavin H. Imperato (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mali, fourth Edition. Published by Historical Dictionary of Africa No. 107. Scarecrow Press. Inc.

- ^ Joseph R. Rudolph Jr. (2015). Encyclopedia of Modern Ethnic Conflicts, 2nd Edition [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-61069-553-4.

- ^ Tamasheq: A language of Mali, Ethnologue

- ^ Mali, CIA Factbook, Accessed on 7 November 2016

- ^ Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress M1 The Berbers Wiley Blackwell 1997 ISBN 978-0631207672 p. 208

- ^ Briggs, L. Cabot (February 1957). "A Review of the Physical Anthropology of the Sahara and Its Prehistoric Implications". Man. 56: 20–23. doi:10.2307/2793877. JSTOR 2793877.

- ^ Nicolaisen, Johannes and Ida Nicolaisen. The Pastoral Tuareg: Ecology, Culture and Society Vol. I & II. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997, p. 31.

- ^ "Tuareg Confederacies, Federations & Twareg Territories of North Africa:الطوارق". temehu.com.

- ^ Travels in the Great Desert of Sahara, in the Years of 1845 and 1846 Containing a Narrative of Personal Adventures, During a Tour of Nine Months Through the Desert, Amongst the Touaricks and Other Tribes of Saharan People; Including a Description of the Oases and Cities of Ghat, Ghadames, and Mourzuk by James Richardson Project Gutenberg Release Date: July 17, 2007 [EBook #22094] Last Updated: April 7, 2018

- ^ "Charles de Foucauld – Sera béatifié à l'automne 2005". Archived from the original on 23 October 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Charles de Foucauld – Sera béatifié à l'automne 2005". Archived from the original on 23 October 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Hall, B.S. (2011) A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ISBN 9781139499088, pp. 181–182

- ^ a b "Does Supply-Induced Scarcity Drive Violent Conflicts in the African Sahel? The Case of the Tuareg Rebellion in Northern Mali" (Nov., 2008) Journal of Peace Research Vol. 45, No. 6

- ^ "A Political Analysis of Decentralisation: Coopting the Tuareg Threat in Mali" (Sep. 2001) The Journal of Modern African Studies Vol. 39, No. 3

- ^ "A Political Analysis of Decentralisation: Coopting the Tuareg Threat in Mali" (Sep. 2001) The Journal of Modern African Studies Vol. 39, No. 3

- ^ Denise Youngblood Coleman (June 2013). "Niger". Country Watch. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Jane E. Goodman (2005) Berber Culture on the World Stage: Village to Video, Indiana University Press ISBN 978-0253217844

- ^ "Berbers: Armed movements". Flags Of The World. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Elischer, Sebastian (12 February 2013). "After Mali Comes Niger". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Macé, Célian. "Au Niger, l'escalade macabre de l'Etat islamique". Libération (in French). Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Ouachi, Moustapha. The Berbers and the death. El-Haraka.

- ^ Ouachi, Moustapha. The Berbers and rocks. El-Haraka.

- ^ "The Tuareg the Nomadic inhabitants of North Africa". Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Wolfgang Weissleder (1978). The Nomadic Alternative: Modes and Models of Interaction in the African-Asian Deserts and Steppes. Walter de Gruyter. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-11-081023-3., Quote: "The religion of the Tuareg is Maliki Sunni Islam"

- ^ Schlichte, Klaus (1 March 1994). "Is ethnicity a cause of war?". Peace Review. 6 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1080/10402659408425775. ISSN 1040-2659.

- ^ Susan Rasmussen (2013). Neighbors, Strangers, Witches, and Culture-Heroes: Ritual Powers of Smith/Artisans in Tuareg Society and Beyond. University Press of America. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7618-6149-2., Quote: "Historically, Tuareg and other Berber (Amazigh) peoples initially resisted Islam in their mountain and desert fortresses"

- ^ Bruce S. Hall (2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-139-49908-8., Quote: "We remind ourselves that the Tuareg carries this name for having long resisted and refused Islamization."

- ^ John O. Hunwick (2003). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613. BRILL Academic. pp. 29 with footnote 1 and 2. ISBN 978-90-04-12822-4.

- ^ John Hunwick (2003). "Timbuktu: A Refuge of Scholarly and Righteous Folk". Sudanic Africa. 14. Brill Academic: 13–20. JSTOR 25653392.

- ^ John Glover (2007). Sufism and Jihad in Modern Senegal: The Murid Order. University of Rochester Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-58046-268-6.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 6.

- ^ Monroe, J. Cameron (2018). ""Elephants for Want of Towns": Archaeological Perspectives on West African Cities and Their Hinterlands". Journal of Archaeological Research. 26 (4): 387–446. doi:10.1007/s10814-017-9114-2.

- ^ Kevin Shillington (2012). History of Africa. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-1-137-00333-1.

- ^ Johannes Nicolaisen (1963). Ecology and Culture of the Pastoral Tuareg. New York: Thames and Hudson; Copenhagen: Rhodos. pp. 411–412. OCLC 67475747.

- ^ a b Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Joseph Rudolph Jr. (2015). Encyclopedia of Modern Ethnic Conflicts, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 380–381. ISBN 978-1-61069-553-4., Quote: "The Tuareg are seminomadic people of Berber origin. There are various Tuareg clans and confederation of clans. Historically, Tuareg groups are composed of hierarchical caste systems within clans, including noble warriores, religious leaders, craftsmen, and those who are unfree".

- ^ a b c d e f Jeffrey Heath (2005). A Grammar of Tamashek, Tuareg of Mali. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-3-11-090958-6.

- ^ a b Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Karl G. Prasse 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Karl G. Prasse 1995, p. 20.

- ^ a b Karl G. Prasse 1995, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Stewart, C. C. (1977). "The Tuaregs: Their Islamic Legacy and its Diffusion in the Sahel. By H. T. Norris". Africa. 47 (4): 423–424. doi:10.2307/1158348. JSTOR 1158348. S2CID 140786332.

- ^ Heath, Jeffrey (2005). A Grammar of Tamashek (Tuareg of Mali). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110909586. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Karl G. Prasse 1995, p. 18.

- ^ David C. Conrad; Barbara E. Frank (1995). Status and Identity in West Africa. Indiana University Press. pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-0-253-11264-4.

- ^ Ruth M. Stone (2010). The Garland Handbook of African Music. Routledge. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-1-135-90001-4., Quote: "In Mali, Niger and southern Algeria, Tuareg griots of the artisanal caste practice a related tradition. Known to the Tuareg as agguta, they typically entertain at weddings (...)"

- ^ Susan Rasmussen (1996), Matters of Taste: Food, Eating, and Reflections on "The Body Politic" in Tuareg Society, Journal of Anthropological Research, University of Chicago Press, Volume 52, Number 1 (Spring, 1996), page 61, Quote: "'Nobles are like rice, smiths are like millet, and slaves are like corn', said Hado, a smith from the Kel Ewey confederation of Tuareg near Moun Bagzan in northeastern Niger. He was explaining to me the reasons for endogamy."

- ^ a b c Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Bruce S. Hall (2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5, 7–8, 220. ISBN 978-1-139-49908-8.

- ^ Gaston, Tony (15 October 2019). African Journey: A Voyage on the Sea of Humanity. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-5255-4981-6.

- ^ a b Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 18, 50–54.

- ^ a b Nicolaisen, Johannes (1963). Ecology and Culture of the Pastoral Tuareg: With Particular Reference to the Tuareg of Ahaggar and Ayr. National Museum of Copenhagen. p. 16. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Hsain Ilahiane (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Scarecrow. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-8108-6490-0., Quote: "IKLAN. This term refers to all former black slaves and domestic serfs of traditional Tuareg society. The term iklan is plural form for'slave'."

- ^ Gregory Mann (2014). From Empires to NGOs in the West African Sahel. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–111 with footnote 73. ISBN 978-1-107-01654-5.

- ^ Starratt, Priscilla Ellen (1981). "Tuareg slavery and slave trade". Slavery & Abolition. 2 (2): 83–113. doi:10.1080/01440398108574825.

- ^ Karl G. Prasse 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Martin A. Klein (1998). Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7.

- ^ Martin A. Klein (1998). Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. xviii, 138–139. ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7.

- ^ Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Karl G. Prasse 1995, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Edouard Bernus. "Les palmeraies de l'Aïr", Revue de l'Occident Musulman et de la Méditerranée, 11, (1972) pp. 37–50;

Frederick Brusberg. "Production and Exchange in the Saharan Aïr ", Current Anthropology, Vol. 26, No. 3. (Jun., 1985), pp. 394–395. Field research on the economics of the Aouderas valley, 1984.;

Michael J. Mortimore. "The Changing Resources of Sedentary Communities in Aïr, Southern Sahara", Geographical Review, Vol. 62, No. 1. (Jan., 1972), pp. 71–91. - ^ Martin A. Klein (1998). Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7.

- ^ Klein (1998) pp.111–140

- ^ Klein (1998) p. 234

- ^ Klein (1998) pp. 234–251

- ^ a b c Klein (1998) "Appendix I:How Many Slaves?" pp. 252–263

- ^ Kohl, Ines; Fischer, Anja (31 October 2010). Tuareg Society within a Globalized World. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857719249. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Anti-Slavery International & Association Timidira, Galy kadir Abdelkader, ed. Niger: Slavery in Historical, Legal and Contemporary Perspectives Archived 6 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. March 2004

- ^ Hilary Andersson, "Born to be a slave in Niger", BBC Africa, Niger;

"Kayaking to Timbuktu, Writer Sees Slave Trade, More", National Geographic.;

"The Shackles of Slavery in Niger". ABC News. 3 June 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2013.;

"Niger: Slavery – an unbroken chain". Irinnews.org. 21 March 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2013.;

"On the way to freedom, Niger's slaves stuck in limbo", Christian Science Monitor - ^ "The Shackles of Slavery in Niger", ABC News

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (1 June 2013). "Timbuktu's slaves liberated as Islamists flee". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Mali slavery problem persists after French invasion". USA TODAY. 14 February 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b Susan McIntosh (2001). Christopher R. DeCorse (ed.). West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade: Archaeological Perspectives. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-7185-0247-8.

- ^ Adda Bruemmer Bozeman (2015). Conflict in Africa: Concepts and Realities. Princeton University Press. pp. 280–282 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-4008-6742-4.

- ^ David C. Conrad; Barbara E. Frank (1995). Status and Identity in West Africa. Indiana University Press. pp. 75–77, 79–81. ISBN 978-0-253-11264-4.

- ^ Tamari, Tal (1991). "The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa". The Journal of African History. 32 (2): 221–250. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025718. S2CID 162509491.

- ^ Susan McIntosh (2001). Christopher R. DeCorse (ed.). West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade: Archaeological Perspectives. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-7185-0247-8.

- ^ a b Haven, Cynthia (23 May 2007). "New exhibition highlights the 'artful' Tuareg of the Sahara". News.stanford.edu. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

A Stanford Univ. news article of 23 May 2007

- ^ Spain, Daphne (1992). Gendered Spaces. Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2012-1, p. 57.

- ^ a b Murphy, Robert F. (Apr1966). Untitled review of a 1963 major ethnographic study of the Tuareg. American Anthropologist, New Series, 68 (1966), No.2, 554–556.

- ^ Ebenhard, David; Simons, Gary; Fennig, Charles, eds. (2019). "Tamajaq, Tawallammat". Ethnoloque. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (2015). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 481. ISBN 978-0810879195. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Loughran 2006, pp. 167–212

- ^ Dieterlen, Germaine; Ligers, Ziedonis (1972). "Contribution à l'étude des bijoux touareg". Journal des Africanistes. 42 (1): 29–53. doi:10.3406/jafr.1972.1697.

- ^ Ludwig G. A. Zöhrer, Die Tuareg der Sahara, 1956, p.182

- ^ Société d'anthropologie de Paris, Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, 1902, p.633

- ^ Seligman and Loughran (2006), The cross of Agadez as a national and political symbol, pp. 258- 261

- ^ Seligman and Loughran (2006), The cross of Agadez, pp. 251–265

- ^ Prussin, Labelle "African Nomadic Architecture" 1995.

- ^ a b Scelta, Gabe (2011). "Much to Learn About Living: Tuareg Architecture and Reflections of Knowledge" (paper).

- ^ Rasmussen, Susan (1996). "The Tent as Cultural Symbol and Field Site: Social and Symbolic Space, "Topos", and Authority in a Tuareg Community". Anthropological Quarterly. 69 (1): 14–26. doi:10.2307/3317136. JSTOR 3317136.

- ^ Rasmussen, Susan J. (1998). "Within the Tent and at the Crossroads: Travel and Gender Identity among the Tuareg of Niger". Ethos. 26 (2): 164. doi:10.1525/eth.1998.26.2.153.

- ^ "First Exhibition of Tuareg Art and Culture in America Appears at Stanford Before Traveling to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art" Archived 29 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Cantor Arts Center

- ^ Deycard, Frédéric (2011). "Political Cultures and Tuareg mobilizations: Rebels of Niger, from Kaocen to the Mouvement des Nigériens pour la Justice". In Guichaoua, Yvan (ed.). Understanding Collective Political Violence. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 46–64. ISBN 9780230285460.

- ^ "Robert Plant Finds Roots in the Sahara," NPR, December 8, 2003, https://www.npr.org/2003/12/08/1532394/robert-plant-finds-blues-roots-in-the-sahara

- ^ "Robert Plant: Desert storm," Independent, August 29, 2003

- ^ Empire, Kitty (24 April 2005). "Led Zeppelin meet the Tuaregs". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Gentile, John (11 November 2013). "Robert Plant Takes a Trip to Mali". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Abada, Latifa (10 September 2016). "La fête Touareg "Sebiba" célébrée en octobre à Djanet". Al Huffington Post (in French). Archived from the original on 1 October 2016.

- ^ "A Love Apart – Bettina Haasen". Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Mdou Moctar – Akounak Teggdalit Taha Tazoughai TEASER". YouTube. 26 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Mdou Moctar protagoniza un nuevo filme documental: "Rain the Color of Red with a Little Blue in It"". conceptaradio. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Sahel Sounds: "Algunos artistas africanos nunca han visto un vinilo"". conceptoradio. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Mdou Moctar – Akonak (TEASER TRAILER 2)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Kirkley, Christopher (19 July 2017), Zerzura (Western), Ibrahim Affi, Zara Alhassane, Habiba Almoustapha, Imouhar Studio, Sahel Sounds, retrieved 13 September 2024

- ^ "Who are the Tuareg?". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Hibbs, Mark. "Uranium in Saharan Sands". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Pádraig Carmody. The New Scramble for Africa. Polity. (2011) ISBN 9780745647852

- ^ a b c d e Ottoni, C; Larmuseau, MH; Vanderheyden, N; Martínez-Labarga, C; Primativo, G; Biondi, G; Decorte, R; Rickards, O (May 2011). "Deep into the roots of the Libyan Tuareg: a genetic survey of their paternal heritage". Am J Phys Anthropol. 145 (1): 118–24. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21473. PMID 21312181.

- ^ a b Pereira; et al. (2010). "Y chromosomes and mtDNA of Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.21. PMC 2987384. PMID 20234393.

- ^ "E-M81 YTree". www.yfull.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Cruciani, Fulvio; Fratta, Roberta La; Santolamazza, Piero; Sellitto, Daniele; Pascone, Roberto; Moral, Pedro; Watson, Elizabeth; Guida, Valentina; Colomb, Eliane Beraud; Boriana Zaharova; Lavinha, João; Vona, Giuseppe; Aman, Rashid; Calì, Francesco; Akar, Nejat; Richards, Martin; Torroni, Antonio; Novelletto, Andrea; Scozzari, Rosaria (May 2004). "Phylogeographic analysis of haplogroup E3b (E-M215) y chromosomes reveals multiple migratory events within and out of Africa". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1014–22. doi:10.1086/386294. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

- ^ Arredi B, Poloni ES, Paracchini S, Zerjal T, Fathallah DM, Makrelouf M, Pascali VL, Novelletto A, Tyler-Smith C (2004). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa". Am J Hum Genet. 75 (2): 338–345. doi:10.1086/423147. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

- ^ Ottoni (2010). "Mitochondria Haplogroup H1 in North Africa: An Early Holocene Arrival from Iberia". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13378. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513378O. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.350.6514. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013378. PMC 2958834. PMID 20975840.

- ^ a b c Luísa Pereira; Viktor Černý; María Cerezo; Nuno M Silva; Martin Hájek; Alžběta Vašíková; Martina Kujanová; Radim Brdička; Antonio Salas (17 March 2010). "Linking the sub-Saharan and West Eurasian gene pools: maternal and paternal heritage of the Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.21. PMC 2987384. PMID 20234393.

- ^ Ottoni, Claudio; Martínez-Labarga, Cristina; Loogväli, Eva-Liis; Pennarun, Erwan; Achilli, Alessandro; De Angelis, Flavio; Trucchi, Emiliano; Contini, Irene; Biondi, Gianfranco; Rickards, Olga (20 May 2009). "First genetic insight into Libyan Tuaregs: a maternal perspective". Annals of Human Genetics. 73 (Pt 4): 438–448. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00526.x. ISSN 1469-1809. PMID 19476452. S2CID 31919422.

- ^ Pereira, Luisa; et al. (2010). "Linking the sub-Saharan and West Eurasian gene pools: maternal and paternal heritage of the Tuareg nomads from the African Sahel". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.21. PMC 2987384. PMID 20234393.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Cavalli-Sforza, Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.

- ^ Arauna, Lara R; Comas, David (15 September 2017). "Genetic Heterogeneity between Berbers and Arabs". eLS: 1–7. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0027485. ISBN 9780470016176.

Bibliography

- Heath Jeffrey 2005: A Grammar of Tamashek (Tuareg of Mali). New York: Mouton de Gruyer. Mouton Grammar Library, 35. ISBN 3-11-018484-2

- Hourst, Lieutenant (1898) (translated from the French by Mrs. Arthur Bell) French Enterprise in Africa: The Exploration of the Niger. Chapman Hall, London.

- Loughran, Kristyne (2006). "Tuareg women and their jewelry". In Seligman, Thomas K.; Loughran, Kristyne (eds.). Art of being Tuareg: Sahara nomads in a modern world. Los Angeles: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. pp. 167–212. ISBN 978-0-9748729-4-0. OCLC 61859773.

- Karl G. Prasse (1995). The Tuaregs: The Blue People. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-313-6.

- Karl Prasse; Ghoubeid Alojaly; Ghabdouane Mohamed (2003). Dictionnaire touareg-français. Copenhague, Museum Tusculanum. ISBN 978-87-7289-844-5.

- Rando et al. (1998) "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of northwest African populations reveals genetic exchanges with European, near-eastern, and sub-Saharan populations". Annals of Human Genetics 62(6): 531–50; Watson et al. (1996) mtDNA sequence diversity in Africa. American Journal of Human Genetics 59(2): 437–44; Salas et al. (2002) "The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape". American Journal of Human Genetics 71: 1082–1111. These are good sources for information on the genetic heritage of the Tuareg and their relatedness to other populations.

- Rasmussen, Susan (September 2021). Jain, Andrea R. (ed.). "Re-Thinking a Matrilineal Myth of Healing: Tuareg Medicine Women, Islam, and the Market in Niger". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 89 (3). Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Religion: 909–930. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfab076. eISSN 1477-4585. JSTOR 00027189. LCCN sc76000837.

- Francis James Rennell Rodd, People of the veil. Being an account of the habits, organisation and history of the wandering Tuareg tribes which inhabit the mountains of Aïr or Asben in the Central Sahara, London, MacMillan & Co., 1926 (repr. Oosterhout, N.B., Anthropological Publications, 1966)

- Saad, Elias N. (1983), Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24603-2

Further reading

- Edmond Bernus, "Les Touareg", pp. 162–171 in Vallées du Niger, Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993.

- Andre Bourgeot, Les Sociétés Touarègues, Nomadisme, Identité, Résistances, Paris: Karthala, 1995.

- Hélène Claudot-Hawad, ed., "Touaregs, exil et résistance". Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée, No. 57, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1990.

- Claudot-Hawad, Touaregs, Portrait en Fragments, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1993.

- Hélène Claudot-Hawad and Hawad, "Touaregs: Voix Solitaires sous l'Horizon Confisque", Ethnies-Documents No. 20–21, Hiver, 1996.

- Mano Dayak, Touareg: La Tragedie, Paris: Éditions Lattes, 1992.

- Sylvie Ramir, Les Pistes de l'Oubli: Touaregs au Niger, Paris: éditions du Felin, 1991.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 352.

- Tuareg Culture and Art, Bradshaw Foundation

- Franco Paolinellli, "Tuareg Salt Caravans", Bradshaw Foundation

- Who are the Tuareg? Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World

- Tuareg children picture