Torsion mangonel myth

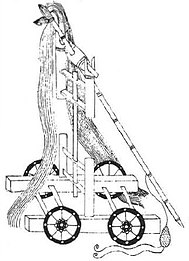

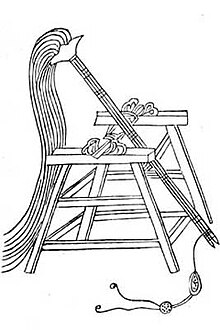

The torsion mangonel myth, or simply the myth of the mangonel,[1] is the belief that the mangonel (or traction trebuchet) was a torsion siege engine which used the tension effect of twisted cords to shoot projectiles, and is considered by some to have been in use until the arrival of gunpowder artillery. Instead, the mangonel operated on manpower-pulling cords attached to a lever and sling to launch projectiles.[2]

Evidence for the usage of torsion siege weapons such as the onager exist only up until the 6th century, when they were superseded by traction artillery (with the exception of the springald).[3][4]

Despite a significant body of research dating as far back as the 19th century pointing to the contrary, "it has not stopped the transmission of the myth to the present day."[5]

Historiography

The torsion mangonel myth began in the 18th century when Francis Grose claimed that the onager was the dominant medieval artillery until the arrival of gunpowder. In the mid-19th century, Guillaume Henri Dufour adjusted this framework by arguing that onagers went out of use in medieval times, but were directly replaced by the counterweight trebuchet. Dufour and Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte argued that torsion machines were abandoned because the requisite supplies needed to build the sinew skein and metal support pieces were too difficult to obtain in comparison to the materials needed for tension and counterweight machines.[7][8][9]

In the early 20th century, Ralph Payne-Gallwey concurred that torsion catapults were not used in medieval times, but only owing to their greater complexity, and believed that they were superior to "such a clumsy engine as the medieval trebuchet."[10] Others such as Gustav Köhler, D.J. Cathcart King, Jim Bradbury, Christopher Marshall, and David Bachrach disagreed and argued that torsion machines were used throughout the Middle Ages.[11][12]

Bradbury says that "Direct evidence for them in the earlier medieval period is not strong; but evidence for any specific type of thrower is weak until about the twelfth century."[13] According to Bradbury, since the Roman world and the later middle ages both possessed torsion weapons, and a variety of artillery appears to have existed between those eras, he is "prepared to accept the probable existence of torsion engines, but without insisting that mangonellus, tormentum, or any other single term necessarily implied a torsion weapon."[14]

The idea of a torsion powered mangonel is particularly appealing for many historians due to its potential as an argument for the continuity of classical technologies and scientific knowledge into the Early Middle Ages, which they use to refute the concept of medieval decline.[15] According to W.T.S. Tarver, the Renaissance "fostered the lingering notion that all things Roman were perfect,"[16] that the "Romans had siege engines; therefore the Romans had the best siege engines imaginable."[16] The Renaissance drawings of fictitious machines later became confused with real ones while depictions of ancient machines were "based on fragments of ancient descriptions."[16] This in turn led to erroneous assumptions about siege engines that have "discredited the traction trebuchet as a real historical phenomenon."[17] Those who support the continued use of torsion artillery such as the onager after the 6th century have been called the "continuist" school of thought while their opponents called the "discontinuist" school.[18]

In 1910, Rudolph Schneider pointed out that medieval Latin texts are completely devoid of any description of the torsion mechanism. He proposed that all medieval terms for artillery actually referred to the trebuchet, and that the knowledge to build torsion engines had been lost since classical times.[19] In 1941, Kalervo Huuri argued that the onager remained in use in the Mediterranean region, but not ballistas, until the 7th century when "its employment became obscured in the terminology as the traction trebuchet came into use."[20][21]

In 1995, W.T.S. Tarver considered the traction powered machines to have provided a viable alternative to the "onager soon after the collapse of the Roman Empire and long before the introduction of the counterweight trebuchet in the 12th century."[6] In 1997, Randall Rogers deemed it relatively certain that two-armed stone throwing machines (ballistas) were not used during medieval times, and although it is difficult to prove that one-armed ones (onagers) were not, he could not find any evidence that they were.[22] In 1999, John France concluded that it was traction trebuchets that were used during the First Crusade.[23] Similarly, Paul E. Chevedden considered the onager's days to be numbered by the 6th century, by the end of which "a new stone-projector, the traction trebuchet, had appeared in the Mediterranean."[24]

In 2006, Peter Purton called the continuation of torsion-artillery as the mangonel a myth.[25] In 2018, Michael S. Fulton noted that there is "insufficient evidence at this time to conclusively prove or disprove that the use of torsion stone-throwers continued through the Middle Ages,"[26] but traction trebuchets appear to have been the most common, or only, mechanical stone thrower during the First Crusade.[26] However there are still those who support the continued usage of torsion stone throwers as late as the 11th century.[27] According to Bachrach writing in 2021, "Today, many scholars agree that both torsion and tension technology were used in the post-Roman West."[28]

Evidence of medieval torsion weapons

By the 9th century, when the first Western European reference to a mangana (mangonel) appeared, there is virtually no evidence at all, whether textual or artistic, of torsion engines used in warfare. The last historical texts specifying a torsion engine aside from the springald date no later than the 6th century.[5] By the mid-10th century, Constantine VII's list of Byzantine artillery weapons and their descriptions contained only traction-powered machines. The exception to this dearth of textual evidence is an anonymous writer under the name of Heron of Byzantium, who repeats ancient descriptions of the onager. However its accompanying illustrations show only the traction trebuchet.[3] Dietwulf Baatz argued that Heron's text was proof that the onager "lasted for centuries into the Byzantine period."[32] The text was copied throughout the Byzantine period, which Chevedden believes "may simply indicate a conservative archaistic literary tradition, rather than evidence."[32]

Some historians such as Randall Rogers and Bernard Bachrach have argued that the lack of evidence regarding torsion siege engines does not provide enough proof that they were not used, considering that the narrative accounts of these machines almost always do not provide enough information to definitively identify the type of device being described, even with illustrations.[33] Bachrach believes that torsion artillery continued to exist as late as the 11th century based on size differences between artillery weapons mentioned. Writing in the late 9th century, Abbo Cernuus described mangana throwing large stones while catapultae threw pots of melted led. Abbo also mentioned catapultae mounted on city walls, which Bachrach interpreted as a function of their smaller size, and thus proof that they were torsion stone throwers, while the mangana were larger traction trebuchets that had to be positioned on the ground.[34]

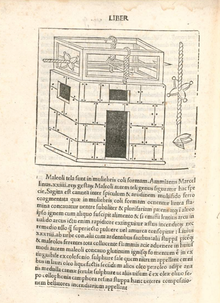

Medieval illustrations of an onager do not appear until the 14th-15th centuries. The earliest medieval depiction of an onager is from Walter de Milemete's De nobilitatibus, sapientiis, et prudentiis regum of 1326, the same source for Europe's earliest cannon. Fulton notes that the engine appears oddly shaped, impractical, and likely based on the illustrator's interpretation of an onager derived from classical descriptions.[29][35][36][37] While definitions for artillery terms are hard to pin down, artistic evidence of traction trebuchets confirms that knowledge of them was widespread in comparison to torsion artillery.[38]

With the exception of bolt throwers such as the springald which saw action from the 13th to 14th centuries and possibly the ziyar in the Muslim world,[39][40][41] torsion machines had largely disappeared by the 6th century and were replaced by the traction trebuchet. This does not mean torsion machines were completely forgotten since classical texts describing them were circulated in medieval times. For example, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou had a copy of Vegetius at the siege of Montreuil-Bellay in 1147, yet judging from the description of the siege, the weapon they used was a traction trebuchet rather than a torsion catapult.[42]

... anyone consulting Bradbury’s Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare (2004) will find mangonels described as stone-throwing catapults powered by the torsion effect of twisted ropes... But the truth is that there is no evidence for its medieval existence at all. Of course, it is hard to prove that something was not there (as opposed to proving that something was), but this is not a new finding: a considerable body of learned research dating back to the 19th century had reached that conclusion. But it has not stopped the transmission of the myth to the present day.[5]

In the enormous quantity of surviving illuminated manuscripts, the illustrations have always given us valuable clues about warfare. In all this mass of illustrations, there are numerous depictions of manually operated stone throwers, then of trebuchets and, finally, of bombards and other types of weapon and siege equipment. Taking into consideration the constraints under which the monastic artists were working, and their purpose (which was not, of course, to provide a scientifically precise depiction of a particular siege), such illustrations are often remarkably accurate. Not once, however, is there an illustration of the onager. Unless there was some extraordinary global conspiracy to deny the existence of such weapons, one can only conclude that they were unknown to medieval clerics.[43]

There is no evidence whatever for the continuation of the onager in Byzantium beyond the end of the 6th century, while its absence in the ‘barbarian’ successor kingdoms can be shown, negatively, by the absence of any reference and, logically, from the decline in the expertise needed to build, maintain and use the machine. When the mangonel appeared in Europe from the east (initially in the Byzantine world), it was a traction-propelled stone thrower. Torsion power went out of use for some seven centuries before returning in the guise of the bolt-throwing springald, deployed not as an offensive, wallbreaking siege engine, but to defend those walls against human assailants.[25]

— Peter Purton

Springald

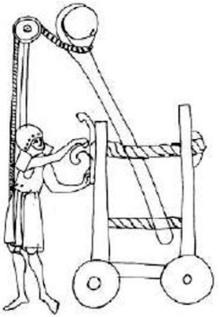

As for the springald, it was a defensive torsion bolt thrower based on the design of ancient ballistas, with two arms held in a skein of twisted sinew or hair. Unlike the ballista, it seems to have been housed in a rectangular box-like wooden structure and it shot bolts instead of stones. According to computer models and projections, a springald could throw a bolt around 180 m (590 ft) if mounted on a tower at an elevation of 15 degrees. It appears to have spread across Europe rapidly during the 13th century.[44]

According to J Liebel, its appearance may be connected to the invention of the spinning wheel in Europe around 1250, which made the winding of skeins easier. The earliest reference to the springald appears in France in 1249 and its presence is attested to in the arsenal at Reims in 1258. In England, an order of horsehair was made for springalds in 1266. Springalds were commonly used to defend gates from atop towers, where their skeins were safe from wet weather and their bolts could be shot a greater distance.[44]

Springalds were expensive to produce: Liebel's calculation for the cost of machines built for the pope at Avignon puts them at six months' worth of wages for an unskilled laborer. By 1382, springalds were being phased out in favor of crossbows or firearms. In some parts of Germany and Switzerland, the springald survived until the early 15th century.[44]

Terminology

Contributing to the torsion mangeonel myth is the muddled usage of the term mangonel. Mangonel was used as a general medieval catch-all for stone throwing artillery, which probably meant a traction trebuchet from the 6th to 12th centuries, between the disappearance of the onager and the arrival of the counterweight trebuchet. Many historians have argued for the continued use of onagers into medieval times on the basis of terminology. For example at the end of the 19th century, Gustav Köhler contended that the petrary was a traction trebuchet, invented by Muslims, whereas the mangonel was a torsion catapult.[45]

John France suggests that different terms for siege engines such as petraria, mangana, mangonella, and tortentum referred to size categories instead.[23] The word petraria appeared in the 7th century and became synonymous with manganon by the 9th century. Paul the Deacon considered petraria and mangonella to be the same thing. Neither have been confirmed to be separate categories of machines working on different types of mechanisms.[45][46]

In the late 9th century, Abbo Cernuus described mangana throwing large stones while catapultae threw pots of molten lead. According to Bachrach, this meant mangana were traction trebuchets because of their greater size while catapultae were torsion machines because they were stationed on city walls, and thus smaller.[27] In the 12th century, William of Tyre noted that the mangana threw smaller stones than certain other unspecified engines. By the 12th century, petrary had become the most common term for identifying artillery in Latin texts.[45] In 2007, Mark Denny defined "mangonel" as trebuchets with fixed counterweights in contrast to "trebuchets", which had hinged counterweights.[47]

Even disregarding definition, sometimes when the original source specifically used the word "mangonel," it was translated as a torsion weapon such as the ballista instead, which was the case with an 1866 Latin translation of a Welsh text.[48] This further adds to the confusion in terminology since "ballista" was used in medieval times as well, but probably only as a general term for stone throwing machines. For example Otto of Freising referred to the mangonel as a type of ballista, by which he meant they both threw stones.[49] The Middle English Dictionary confuses the trebuchet with the ballista and describes it shooting projectiles such as darts.[50] A Bible translation dating to about 1425 anachronistically describes the construction of trebuchets.[50]

There are references to Arabs, Saxons, and Franks using ballistae but it is never specified whether or not these were torsion machines.[51] It is stated that during the siege of Paris in 885-886, when Rollo pitted his forces against Charles the Fat, seven Danes were impaled at once with a bolt from a funda.[52][53] It is never stated that the machine used a torsion mechanism, similar to uses of other terminology such as mangana by William of Tyre and William the Breton to indicate small stone-throwing engines, or "cum cornu" ("with horns") in 1143 by Jacques de Vitry.[14]

Sometimes terms were translated as mangonel in later texts even though it was not used in the original. William of Tyre mentioned the use of machinae during the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), but this was translated as perriers and mangoniaux in the later Estoire d'Eracles, and as petrariae and trebuculi by Roger of Wendover.[45] This was also the case with the second siege of Tyre in 1124, where Fulcher of Chartres and William of Tyre mention the use of machinae and machinae iaculatoriae, but was later translated as perrieres and mangoniaux in the Estoire d'Eracles.[54]

The best arguments for the continued use of torsion artillery in Europe after the sixth century are the continued use of classical terms and the lack of conclusive evidence that they were not used; but neither of these arguments is particularly strong. Such engines were less powerful, more complicated, and far more dangerous to operate than swing-beam engines, given the pent-up stresses within the coil and then violent stop of the arm against a component of the framework when fired. Traction trebuchets, by comparison, were capable of a much higher rate of fire and were far simpler to construct, use and maintain.[23]

— Michael S. Fulton

In modern times the mangonel is often confused with the onager due to the torsion mangonel myth. Modern military historians came up with the term "traction trebuchet" to distinguish it from previous torsion machines such as the onager.[55] However traction trebuchet is a newer modern term that is not found in contemporary sources,[56] which can lead to further confusion. For some, the mangonel is not a specific type of siege weapon but a general term for any pre-cannon stone throwing artillery. Onagers have been called onager mangonels,[57] traction trebuchets called "beam-sling mangonels",[58][59][60] and the counterweight trebuchet called "counterweight mangonel".[61] From a practical perspective, mangonel has been used to describe anything from a torsion engine like the onager, to a traction trebuchet, to a counterweight trebuchet[17][61] depending on the user's bias.[62]

See also

References

- ^ Purton 2006.

- ^ Purton 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b Purton 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 364-365.

- ^ a b c Purton 2006, p. 80.

- ^ a b Tarver 1995, p. 165.

- ^ Dufour 1840, pp. 97, 99.

- ^ Bonaparte, p. 26.

- ^ Chevedden 1999, p. 131.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Köhler 1890, pp. 139–211.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 15-16.

- ^ Bradbury 1992, p. 253.

- ^ a b Bradbury 1992, p. 254.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Tarver 1995, p. 137.

- ^ a b Tarver 1995, p. 138.

- ^ Chevedden 1999, p. 133.

- ^ Schneider 1910, pp. 10–16.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Huuri 1941, pp. 51–63, 212–214.

- ^ Rogers 1997, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Fulton 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Chevedden 1999, p. 164.

- ^ a b Purton 2006, p. 89.

- ^ a b Fulton 2018, p. 4.

- ^ a b Bachrach 2021, p. 238.

- ^ Bachrach 2021, p. 237.

- ^ a b Fulton 2018, p. 454.

- ^ "Murals of the Silk Road - Archaeology Magazine".

- ^ Fulton 2018, p. 420.

- ^ a b Chevedden 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Rogers 1997, pp. 254–273.

- ^ Bachrach 2021, p. 237-238.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Rogers, France & DeVries 2016, p. 3

- ^ Rogers, France & DeVries 2016, p. 2

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Bradbury 1992, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Hacker 1968, p. 43.

- ^ Fulton 2016, p. 10-11.

- ^ Purton 2006, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Purton 2006, p. 85-88.

- ^ a b c d Fulton 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Fulton 2018, p. 26.

- ^ Denny 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 172.

- ^ Nicolle 2002, p. 9-10.

- ^ a b Sayers 2023, p. 96.

- ^ Bradbury 1992, p. 251.

- ^ Bradbury 1992, p. 252.

- ^ Abbo Cernuus (2007). Bella Parisiacae urbis. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042919167.

- ^ Fulton 2018, p. 98.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 365.

- ^ Purton 2018, p. 58.

- ^ "The Onager Mangonel Catapult". COVE Editions. 12 May 2019.

- ^ Nicolle 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Nicolle 2014, p. 40

- ^ "Mangonel Siege Weapon". medievalchronicles.com. 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand 2000, p. 524.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 410.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Bachrach, Bernard S., David S. (2021), Warfare in Medieval Europe c.400-1453, Taylor & Francis

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bradbury, Jim (1992), The Medieval Siege, Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press

- Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet" (PDF). Scientific American. 273 (1): 66–71. Bibcode:1995SciAm.273a..66C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0795-66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-11.. Original version.

- Chevedden, Paul E. (1999), Artillery in Late Antiquity: Prelude to the Middle Ages

- Chevedden, Paul E. (2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 54: 71–116. doi:10.2307/1291833. JSTOR 1291833.

- Dennis, George (1998). "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: The Helepolis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (39).

- Denny, Mark (2007), Ingenium: Five Machines that Changed the World

- Dufour, Guillaume (1840), Mémoire sur l'artillerie des anciens et sur celle de Moyen Âge, Paris: Cherbuliez

- Fulton, Michael S. (2016), Artillery in and around the Latin East

- Fulton, Michael S. (2018), Artillery in the Era of the Crusades

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Gravett, Christopher (1990). Medieval Siege Warfare. Osprey Publishing.

- Hacker, Barton C. (January 1968), "Greek Catapults and Catapult Technology: Science, Technology, and War in the Ancient World", Technology and Culture, 9 (1): 34–50, doi:10.2307/3102042, JSTOR 3102042

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (April 1992). "Medieval Siege Engines Reconstructed: The Witch with Ropes for Hair". Military Illustrated (47): 15–20.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (1992). "Experimental Reconstruction of the Medieval Trebuchet". Acta Archaeologica (63): 189–208. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2000), The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives, Routledge

- Huuri, Kalervo (1941). "Zur Geschicte de mitterlalterlichen Geschützwesens aus orientalischen Quellen". Societas Orientalia Fennica, Studia Orientalia. 9 (3): 50–220.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2000). The Counterweighted Trebuchet – an Excellent Example of Applied Retromechanics.

- Jahsman, William E.; MTA Associates (2001). FATAnalysis (PDF).

- Archbishop of Thessalonike, John I (1979). Miracula S. Demetrii, ed. P. Lemerle, Les plus anciens recueils des miracles de saint Demitrius et la penetration des slaves dans les Balkans. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Köhler, G. (1890), Die Entwickelung des Kriegwesens und der Kriegfürung in der Ritterseit von Mitte des II. Jahrhundert bis du Hussitenkriegen, vol. 3, Breslau: Wilhelm Koebner

- Liang, Jieming (2006). Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity – An Illustrated History.

- Nicolle, David (2002), Medieval Siege Weapons 1, Osprey Publishing

- Nicolle, David (2014). The Conquest of Saxony AD 782–785: Charlemagne's defeat of Widukind of Westphalia. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782008262.

- Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph (1903). "LVIII The Trebuchet". The Crossbow With a Treatise on the Balista and Catapult of the Ancients and an Appendix on the Catapult, Balista and Turkish Bow (Reprint ed.). pp. 308–315.

- Peterson, Leif Inge Ree (2013), Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States, Brill

- Purton, Peter (2006). "The myth of the mangonel: Torsion artillery in the Middle Ages". Arms & Armour. 3: 79–90. doi:10.1179/174962606X99155. S2CID 162238792.

- Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c.450-1200, The Boydell Press

- Purton, Peter (2018), The Medieval Military Engineer: From the Roman Empire to the Sixteenth Century

- Rogers, Randall (1997), Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Rogers, Clifford J.; France, John; DeVries, Kelly, eds. (2016). Journal of Medieval Military History. Vol. XIV. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781783271306.

- Saimre, Tanel (2007), Trebuchet – a gravity operated siege engine. A Study in Experimental Archaeology (PDF)

- Sayers, William (2023), "Chapter 3: The Counterweight Trebuchet, the History of Its Name in Medieval France and Britain, and the Terminology of Its Components in Villard de Honnecourt", The Worlds of Villard de Honnecourt: The Portfolio, Medieval Technology, and Gothic Monuments, Brill

- Schneider, Rudolf (1910), Die Artillerie des Mittelalters, Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung

- Siano, Donald B. (November 16, 2013). Trebuchet Mechanics (PDF).

- Al-Tarsusi (1947). Instruction of the masters on the means of deliverance from disasters in wars. Bodleian MS Hunt. 264. ed. Cahen, Claude, "Un traite d'armurerie compose pour Saladin". Bulletin d'etudes orientales 12 [1947–1948]:103–163.

- Tarver, W.T.S. (1995), The Traction Trebuchet: A Reconstruction of an Early Medieval Siege Engine

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612-1300, Osprey Publishing