Tomás Mejía

Tomás Mejía | |

|---|---|

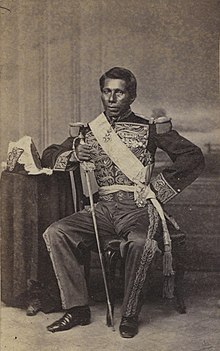

Tomás Mejía c. 1865 | |

| Birth name | José Tomás de la Luz Mejía Camacho |

| Born | 17 September 1820 Pinal de Amoles, Sierra Gorda, Querétaro |

| Died | 19 June 1867 (aged 46) Cerro de las Campanas, Querétaro City, Querétaro |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1841–1867 |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | Mexican–American War Reform War Second Franco-Mexican War |

| Awards | Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Guadalupe (1864) Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle (1865) |

José Tomás de la Luz Mejía Camacho, better known as Tomás Mejía (17 September 1820 – 19 June 1867), was a Mexican soldier of Otomi background, who consistently sided with the Conservative Party throughout its nineteenth century conflicts with the Liberals.

Mejía was one of the leading conservative commanders during the War of Reform and during the French invasion of Mexico which established the Second Mexican Empire. He became known for repeatedly using the Sierra Gorda, which he was familiar with since childhood, as his base of operations. After the fall of the empire, Mejía was executed on 19 June 1867, alongside Emperor Maximilian, and fellow conservative commander Miguel Miramón.

Early life

Little is known about Mejía’s childhood, but he was likely born in Pinal de Amoles, Sierra Gorda, Querétaro. He attended the primary school of the Villa del Jalpan.[1]

His father Cristóbal Mejía was from 1840 to 1842 prefect of the Jalpan district. This was during the Centralist Republic of Mexico when Mexico had been divided into departments, and during which there were many rebellions in favor of states rights which sought to restore the federalist system by which Mexico had previously been governed. One such revolt in 1840 had been led by José de Urrea, who defeated, then found himself in Jalpan by 1841, where Cristóbal Mejía harbored Urrea in his home. The young Tomás Mejía met Urrea and the latter told him war stories and encouraged him in his wishes to join the military.[2]

Early Military Career

Government forces led by Juan Cano then arrived in Jalpan, and Mejía enlisted in the army right there and then. Cano was impressed by the prefect’s son, and his talent for horse riding, writing a letter of recommendation to President Anastasio Bustamante so that Mejía could be admitted to the Military Academy in Mexico City.[3]

Mejía’s first tour of service would be as part of Apache–Mexico Wars, during which he was stationed at Chihuahua City and fought against the Apache from 1842 to 1845. For his service he was promoted in ranks.[4]

Mexican American War

After the United States annexed Texas, and tensions between Mexico and the U.S. were leading to war, Mejía formed part of the Army of the North sent to patrol the Mexican frontier. He was transferred from Chihuahua to Monterrey. After the American invasion began, Mejía followed the Mexican army as it fell back, and he saw action at the Battle of Buena Vista.[5]

The American northern advance under Zachary Taylor stalled after the Battle of Buena Vista, and after the bulk of the Mexican army was called back to the capital to face Winfield Scott’s expedition from the East, Mejía was made part of a garrison that was ordered to stay in the north at San Luis Potosi where he would remain until the end of the war. In 1849, he was granted the rank of commander.[6]

In 1850 during the presidency of Mariano Arista, a revolt flared up in the Sierra Gorda led by the rebel Quiros, and Mejía was among the troops sent to pacify the region. The operation was a success and Quiros was executed at the end of the year. The region had long been a source of instability and president Mariano Arista began to plan a series of military colonies to help maintain order in the region. Mejía was made military commander of the region, but the colonization project was interrupted when the Arista administration was overthrown in 1853 and replaced by Santa Anna. Nonetheless Mejía maintained his post as the region’s political administrator.[7]

The liberal Plan of Ayutla was proclaimed against Santa Anna in 1854, but Mejía remained loyal to the government, and crushed a local revolt. The Plan of Ayutla however continued to gain adherents. The governor of Queretaro, Mejía’s superior, was overthrown, and Mejía attempted to join a counter-revolt, which however surrendered to the government.[8] Mejía would find himself pardoned by the new liberal government.[9]

La Reforma

The Plan of Ayutla would triumph and result in the liberal Juan Álvarez coming to power. Under his administration would begin a series of reforms known as La Reforma which would include a new constitution, and among which were anti-clerical measures intended to strip the Catholic Church of its legal privileges and wealth.

On 25 June 1856, under the presidency of Ignacio Comonfort, the Ley Lerdo was passed, nationalizing lands which were legally held communally. The measure stripped both the Catholic Church and Mexico’s Indigenous communities of the land that they owned, and it was intended to break up the land and sell it to individual owners, under the assumption that this would lead to economic development.

Amidst nationwide conservative revolts, on 13 October, Mejía took over the town of Queretaro, proclaiming his defense of the church and also promising the Indigenous communities to protect their communal lands which had also been affected by the Ley Lerdo. The government sent General Manuel Doblado to take back the city, and Mejía was forced to evacuate it on 21 October, heading towards the Sierra Gorda.[9]

Mejía was now dedicated to waging guerilla warfare while staying based in the Sierra Gorda. General Vicente Rosas Landa attempted to reach a compromise with Mejía, and offered official government recognition of his rank, an arranagment which President Comonfort opposed. Negotiations fell apart, and Mejía went back to the Sierra.[10]

Reform War

The revolts against La Reforma would develop into full blown civil war after President Comonfort joined Félix María Zuloaga's Plan of Ayutla, amounting to a self coup, and which proposed to draft a new, more moderate constitution. Comonfort later backed out of the plan, and left the capital. The constitutional presidency now passed on to the president of the Supreme Court Benito Juarez, while a conservative junta declared Zuloaga to be president. States began to split their allegiances among the rival governments. By April 1858, the liberal Juarez government was esconced in Veracruz, while the conservative government remained in Mexico City. In January 1859, the conservatives chose Miguel Miramon as their new president.

Mejía joined Miramon to occupy the city of San Luis Potosi on 13 September 1858, and they defeated the liberal general Santiago Vidaurri on 29 September.[11]

In April 1859, Mejía was among the conservative troops falling back upon Mexico City where they routed liberal troops under the command of Santos Degollado. On 12 April, Mejía participated in a Mexico City celebration regarding the victory.[12]

On 19 April, Mejía and Marquez were dispatched with a strong army to operate in the state of Michoacan.[13]

The tide of the war began to turn against the conservatives in 1860. Miramon had already failed to capture the liberal capital of Veracruz and another attempt in July of that year failed due to the intervention of the United States Navy. Miramon retreated back to Mexico City as liberal forces closed in on the capital.

Mejía was present at the Battle of Silao at 10 August at which the conservatives were routed. Miramon then retreated to Mexico City.[14] The liberals finally captured Mexico City in January 1861. Mejía was at Queretaro when the conservative government fell, and he escaped afterwards to the Sierra Gorda.[15]

Between the Wars

Mejía now found himself in the city of Jalpan, where he attempted to continue the conservative revolt. He succeeded in capturing the city of Rio Verde and took the garrison commander, Mariano Escobedo prisoner. False stories that Escobedo had been shot circulated in the press, but in reality, Mejía had let him go.[16] Curiously enough, Escobedo would one day be the same commander that would capture Mejía during the Siege of Queretaro, and which would result in Mejía’s execution.

After taking Rio Verde's war supplies, Mejía returned to Jalpan where he joined his forces with those of Leonardo Marquez, the military head of the surviving conservative movement and Ramón Méndez to form an army of about two thousand. Marquez reprimanded Mejía for not having shot Escobedo, warning him that Escobedo would one day in turn have him shot, words that would in the end prove prophetic.[17]

The government sent troops under Manuel Doblado to Jalpan, but Mejía defeated him in multiple skirmishes, before utterly routing him at Cuesta del Huizache, causing Doblado to retreat from the Sierra Gorda.[18]

Mejía remained stationed at Jalpan, while Marquez went on to notable successes, managing to kill the liberal generals Santos Degollado and Leandro Valle Martínez.[19]

In May, Mejía briefly occupied Queretaro City and around the same time President Benito Juarez placed a bounty on Mejía’s head amounting to 10,000 pesos.[19]

Mejía left Queretaro and the Sierra Gorda, heading towards the state of Hidalgo where on 5 July he attacked the city of Huichapan taking all of its garrison prisoner. He then fell back upon the Sierra Gorda to join the rest of the conservative forces which had failed in an attack on Mexico City.[20]

Second French Intervention

In July 1861, President Juárez suspended foreign debt payments in response to a financial crisis, and on 31 October the convention of London, saw Spain, the United Kingdom, and France, agreeing to militarily intervene in Mexico for the sake of pledging Mexico to pay its debts.

On 14 December 1861, a Spanish fleet sailed into and took possession of the port of Veracruz. The city was occupied on 17 December. French and British forces arrived on 7 January 1862. On 10 January, a manifesto was issued by Spanish General Juan Prim disavowing rumors that the allies had come to conquer or to impose a new government. It was emphasized that the three powers merely wanted to open negotiations regarding their claims of damages. On 17 April 1862, Juan Almonte, who had been a foreign minister of the conservative government during the Reform War, and who was brought back to Mexico by the French, released his own manifesto, assuring the Mexican people of benevolent French intentions.[21] Zuloaga and Márquez joined Almonte, but Mejía, who was reluctant to fight for the Spanish, took on an attitude of wait and see.[20]

Meanwhile Spain and the United Kingdom had come to agreements with the Juárez government and departed Mexico as they learned that France intended to overthrow the Mexican government and replace it with a monarchy. On 5 May 1862 Charles de Lorencez's small expeditionary force was repulsed at the Battle of Puebla, and the French army retreated to Orizaba to await reinforcements.

Mejía was meanwhile based in Querétaro, and he published a newspaper expressing his opinions on the ongoing war. Like other conservatives, he did not believe that the French threatened Mexico’s independence, and by October, he openly supported the establishment of the Second Mexican Empire with Maximilian of Habsburg, as its monarch.[22]

By June 1863, the capital had fallen and a conservative, Mexican government had been installed by the French upon which Mejía headed to the capital to offer his services.[23]

Second Mexican Empire

In Mexico City he was received warmly by Marshal Forey, then commander in chief of the French forces in Mexico, who resupplied Mejía s troops.[24] Mejía was then given military command over the interior of the nation.[25]

Mejía was present at the opening of the Assembly of Notables in July, which resolved to found a monarchy and invite Maximilian of Habsburg to assume the throne.[26]

Mejía now took part in the military campaigns by Franco-Mexican forces to consolidate control of the rest of the nation. On 25 December, he captured the city of San Luis Potosi. Two days later liberal forces under Miguel Negrete attempted to take back the city only to be utterly routed, losing all of their war material and leaving nine hundred prisoners. The defeat also resulted in the voluntary surrender of the liberal generals Aramberri, Parrodi, and Ampudia.[27]

In January 1864 Mejía was transferred to Matehuala. In May, liberal forces under Manuel Doblado attempted to take the town, only to suffer a decisive defeat at the hands of Mejía, causing Doblado to leave the nation. Because of this victory, Napoleon III granted Mejía the cross of the Legion of Honour.[28]

On 12 June, Mejía was present at the National Palace at the official reception for the arrival of the royal couple. He was appointed spokesman by the Knights of Guadalupe, and Emperor Maximilian embraced Mejía.[29]

For the second half of 1864, Mejía was stationed in the northeast of the nation working to pacify the region with Charles-Louis Du Pin and Édouard Aymard.[30]

The tide of the Empire began to turn with the conclusion of the American Civil War in April 1865, after which the United States began to supply Mexican Republican forces, and put pressure on France to leave the continent. The Republican General Negrete, with some American mercenaries, began to capture towns along the Rio Grande, and Mejía retreated to Matamoros to await reinforcements.[31]

Mejía protested to the American commandant at Clarksville that American aid and troops was being given to Republican forces, but the commandant replies that such men did so on their own behalf and not on that of the United States government. In spite of that, another American raid cause the U.S. government to remove the commandant from his post and to reprimand the soldiers involved.[32]

As the Empire began to falter, Mejía was forced to retreat from Matamoros on 23 June 1866, and withdraw to Vera Cruz. By December of that year he and his troops found themselves at Guanajuato.[33] By January 1867, French troops had evacuated Mexico. Imperialist forces while retaining control of Mexico City, began to consolidate at Queretaro, where the Emperor and his leading generals, including Mejía, now found themselves.

At a council of war on 22 February 1867, Mejía opposed Marquez’ notion to retreat to Mexico City.[34] On 12 March, republican forces commanded by Mariano Escobedo finally appeared at Queretaro.

The Imperialists held out the siege for the time being and Mejía played his role in repulsing the besieging republicans, but after a few weeks of combat, Mejía was persuaded to support a plan of retreat, which was opposed by Miramon and ultimately not followed through by Maximilian. On 24 March, Mejía once more repulsed another republican assault.[35]

Mejía now fell ill, delaying Imperialist plans of attempting to break through the Republican lines. Nonetheless, Mejía recovered enough to continue plans to escape and seek refuge in Mejía’s old haunt, the Sierra Gorda, where he was well known and regarded amongst the population.[36]

Mejía, and the rest of the imperial leadership were captured on 15 May 1867. Escobedo, whose life had been spared by Mejía six years earlier offered Mejía an escape, but he refused it unless he could be accompanied by Maximilian, and Miramon, terms which Escobedo found unacceptable.[37]

Mejía was tried by a court martial at which he was defended by lawyer Prospero Vega. The defense brought up that previously Mejía had been merciful when capturing the enemy, sparing general Mariano Escobedo, and Jeronimo Trevino, but the court still sentenced Mejía to death.[38] Mejía, Maximilian, and Miramon were shot by firing squad at dawn on 19 June 1867.

Decorations

Mejía was awarded Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Guadalupe in 1864 and Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle in 1865.[39]

In 1865, Napoleon III granted him the cross of the Legion of Honour.[28]

References

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 11.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 16.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 17.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 22.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 22, 24.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Bancroft 1886, p. 699.

- ^ Bancroft 1886, p. 716.

- ^ Bancroft 1886, p. 747.

- ^ Bancroft 1886, p. 764.

- ^ Bancroft 1886, p. 770.

- ^ Bancroft 1886, p. 785.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 68.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 72.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 73.

- ^ a b Diaz 1970, p. 74.

- ^ a b Diaz 1970, p. 76.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, pp. 29, 35, 44.

- ^ Diaz 1970, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 85.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 86.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 61.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 85.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 121.

- ^ a b Bancroft 1888, p. 125.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 146.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 162.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 197.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, pp. 197, 200.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, pp. 252, 256.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 277.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, pp. 284–285, 289.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, pp. 293, 297–298.

- ^ Bancroft 1888, p. 305.

- ^ Diaz 1970, p. 130.

- ^ "Almanaque imperial" (in Spanish). 1866. pp. 214, 216.

Bibliography

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). History of Mexico Volume V. The Bancroft Company.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico VI: 1861-1887. The Bancroft Company.

- Diaz, Fernando (1970). La Vida Heroica del General Tomás Mejía. Editorial Jus.

Further reading

- Fowler, Will. The Grammar of Civil War: A Mexican Case Study, 1857-61. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 2022.

- Hamnett, Brian. "Mexican Conservatives, Clericals and Soldiers: the 'Traitor' Tomás Mejía through Reform and Empire, 1855-1867." Bulletin of Latin American Research 20, no. 2 (2001): 187–209.

External links

![]() Media related to Tomás Mejía at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tomás Mejía at Wikimedia Commons