Tobago

Tobago Alloüebéra • Aloubaéra (Island Carib) Urupina (Galibi Carib) | |

|---|---|

| Ward of Tobago | |

| Etymology: Tabaco (transl. Tobacco) | |

Map of Trinidad and Tobago | |

Location of Tobago in Caribbean | |

| Country | |

| Capital and largest city | Scarborough 11°11′0″N 60°44′15″W / 11.18333°N 60.73750°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Vernacular language | Tobagonian English Creole[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2011)[2] | |

| Religion (2011)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Tobagonian |

| Government | Autonomous administrative division |

| Farley Chavez Augustine | |

| Abby Taylor | |

| Legislature | Tobago House of Assembly |

| National representation | |

| 2 MPs | |

| Area | |

• Total | 300 km2 (120 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2011 census | 60,735[3] |

• Density | 203/km2 (525.8/sq mi) |

| Currency | Trinidad and Tobago dollar (TTD) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +1 (868) |

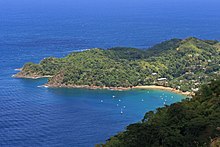

Tobago (/təˈbeɪɡoʊ/) is an island and ward within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located 35 kilometres (22 mi) northeast of the larger island of Trinidad and about 160 kilometres (99 mi) off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. It lies to the southeast of Grenada and southwest of Barbados.

Etymology

Tobago was named Belaforme by Christopher Columbus "because from a distance it seemed beautiful". The Spanish friar Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa wrote that the Kalina (mainland Caribs) called the island Urupina because of its resemblance to a big snail,[4]: 84–85 while the Kalinago (Island Caribs) called it Aloubaéra, supposedly because it resembled the alloüebéra, a giant snake which was supposed to live in a cave on the island of Dominica.[4]: 79 The earliest known record of the use of the name Tabaco to refer to the island is a Spanish royal order issued in 1511. That name was inspired by the resemblance of the shape of the island to the fat cigars smoked by the Taíno inhabitants of the Greater Antilles.[4]: 84–85

History

Indigenous Tobago

Tobago was settled by indigenous people belonging to the Ortoiroid cultural tradition some time between 3500 and 1000 BCE.[4]: 21–24 In the first century of the Common Era, Saladoid people settled in Tobago.[5] They brought with them pottery-making and agricultural traditions, and are likely to have introduced crops which included cassava, sweet potatoes, Indian yam, tannia and corn.[4]: 32–34 Saladoid cultural traditions were later modified by the introduction of the Barrancoid culture, either by trade or a combination of trade and settlement.[4]: 34–44 After 650 CE, the Saladoid culture was replaced by the Troumassoid tradition in Tobago.[4]: 45 Troumassoid traditions were once thought to represent the settlement of the Island Caribs in the Lesser Antilles and Tobago, but this is now associated with the Cayo ceramic tradition. No archaeological sites exclusively associated with the Cayo tradition are known from Tobago.[4]: 60

Tobago's location made it an important point of connection between the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles and their Kalina allies and trading partners in the Guianas and Venezuela. In the 1630s Tobago was inhabited by the Kalina, while the neighbouring island of Grenada was shared by the Kalina and Kalinago.[4]: 115–119

Columbus sighted Tobago on 14 August 1498, during his fourth voyage, but he did not land.[6]: 2 The Spanish settlers in Hispaniola were authorised to conduct slave raids against the island in a royal order issued in 1511.[4] These raids, which continued until at least the 1620s,[4]: 115–119 decimated the island's population.[4]: 83

European colonization

In 1628, Dutch settlers established the first European settlement in Tobago, a colony they called Nieuw Walcheren at Great Courland Bay. They also built a fort, Nieuw Vlissingen, near the modern town of Plymouth. The settlement was abandoned in 1630 after indigenous attacks, but was re-established in 1633. The new colony was destroyed by the Spanish in Trinidad after the Dutch supported a Nepoyo-led revolt in Trinidad. Attempts by the English to colonize Tobago in the 1630s and 1640s also failed due to indigenous resistance.[4]: 115–119

The indigenous population also prevented European colonization in the 1650s, including an attempt by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but the Polish or Lithuanian explorers did not colonize the Island of Tobago, who colonized the island intermittently between 1637 and 1690.[clarification needed] Over the ensuing years, the Curonians (Duchy of Courland), Dutch, English, French, Spanish and Swedish had caused Tobago to become a focal point in repeated attempts of colonization, which led to the island having changed hands 33 times, the most in Caribbean history, before the Treaty of Paris ceded it to the British in 1814. In 1662, the Dutch brothers Adrian and Cornelius Lampsins were granted the title of Barons of Tobago, and ruled until the English captured the island in 1666. Adrian briefly recaptured Tobago in 1673, but was killed in battle when the English, under Sir Tobias Bridge, yet again took control of the island.[7]

From about 1672, during the temporary English rule of 1672–1674,[8] Tobago had a period of stability during which plantation culture began.[citation needed] Sugar, cotton and indigo factories sprang up and Africans were imported by the British to work as slaves. The economy flourished. France had abandoned the island to Britain in 1763,[9] and by 1777 Tobago was exporting great quantities of cotton, indigo, rum and sugar.

In 1781, the French retook the island during the Invasion of Tobago.[10] On 24 May 1781, the fleet of Comte de Grasse landed troops on the island under the command of General Marquis de Bouillé. By 2 June 1781, they had successfully gained control of the island.

British rule and independence

In 1814, when the island again came under British control, another phase of successful sugar-production began.[citation needed] But a severe hurricane in 1847, combined with the collapse of plantation underwriters, end of slavery in 1834 and the competition from sugar with other European countries, marked the end of the sugar trade. In 1889, the island became a ward of Trinidad. Without sugar, the islanders had to grow other crops, planting acres of limes, coconuts and cocoa and exporting their produce to Trinidad. In 1963, Hurricane Flora ravaged Tobago, destroying the villages and crops. A restructuring programme followed and attempts were made[by whom?] to diversify the economy. The development of a tourist industry began.[citation needed]

Trinidad and Tobago obtained independence from the British Empire in August 1962 and became a republic on 31 August 1976.[11]

Geography

Tobago has a land area of 300 km2[3] and is approximately 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) wide. It is located at latitude 11° 15' N, longitude 60° 40' W, slightly north of Trinidad.

The island of Tobago is the main exposed portion of the Tobago terrane, a fragment of crustal material lying between the Caribbean and South American Plates.[12] Tobago is primarily hilly, mountainous and of volcanic origin.[13] The southwest of the island is flat and consists largely of coralline limestone. The mountainous spine of the island is called the Main Ridge. The highest point in Tobago is the 550 metres (1,800 ft) Pigeon Peak near Speyside.[14]

Climate

The climate is tropical, and the island lies just south of the Atlantic Main Development Region, making it vulnerable to occasional low-latitude tropical cyclones. Average rainfall varies between 3,800 mm (150 inches) on the Main Ridge to less than 1,250 mm (49 inches) in the southwest. There are two seasons: a wet season between June and December, and a dry season between January and May.[15]

| Climate data for Tobago (A.N.R. Robinson International Airport) (1973-2004) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.4 (90.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.7 (92.7) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.9 (2.59) |

52.8 (2.08) |

21.4 (0.84) |

52.9 (2.08) |

105.8 (4.17) |

172.5 (6.79) |

266.9 (10.51) |

244.6 (9.63) |

182.6 (7.19) |

240.2 (9.46) |

207.5 (8.17) |

161.0 (6.34) |

1,774.2 (69.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 9.8 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 8.9 | 15.6 | 17.1 | 15.4 | 13.7 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 13.0 | 142.0 |

| Source: NOAA[16] | |||||||||||||

Hurricanes

The island was struck by Hurricane Flora in 1963. The effects were so severe that they changed the face of Tobago's economy. The hurricane laid waste to the banana, coconut, and cacao plantations that largely sustained the economy, and it wreaked considerable damage on the largely pristine tropical rainforest that makes up a large proportion of the interior of the island's northern half. Many of the plantations were subsequently abandoned, and the economy changed direction away from cash crop agriculture and toward tourism. Hurricane Ivan, while less severe than Flora, also caused significant damage in 2004.

Government

Central and local government functions in Tobago are handled by the Tobago House of Assembly. The current Chief Secretary of Tobago is Farley Chavez Augustine from the Progressive Democratic Patriots, which controls 14 of the 15 seats in the Assembly, with the Tobago Council of the People's National Movement led by Ancil Dennis controlling one seat since the December 2021 Tobago House of Assembly election.[17]

Tobago is represented by two seats in the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago, Tobago East and Tobago West. The two seats are controlled by the Tobago Council of the People's National Movement, which won and retained them in the 2015 and 2020 Trinidad and Tobago general election.

Districts

Historically, Tobago was divided into seven parishes (Saint Andrew, Saint David, Saint George, Saint John, Saint Mary, Saint Patrick and Saint Paul). In 1768 each parish of Tobago nominated representatives to the Tobago House of Assembly. On 20 October 1889 the British crown implemented a Royal Order in Council constituting Tobago as a ward of Trinidad, thus terminating local government on Tobago and forming a unified colony government.

In 1945 when the county council system was first introduced, Tobago was administered as a single county of Trinidad.

In 1980 provisions were made for the Tobago House of Assembly to be revived as an entity providing local government in Tobago. Under the revived system, Tobago is made up of 12 local electoral districts with each district electing one Assemblyman to the THA.

| No. | Electoral districts[18] |

|---|---|

| 1 | Bagotelle / Bacolet |

| 2 | Belle Garden / Glamorgan |

| 3 | Bethel / New Grange |

| 4 | Bethesda / Les Coteaux |

| 5 | Bon Accord / Crown Point |

| 6 | Buccoo / Mt. Pleasant |

| 7 | Darryl Spring / Whim |

| 8 | Lambeau / Lowlands |

| 9 | Mason Hall / Moriah |

| 10 | Mt. St. George / Goodwood |

| 11 | Parlatuvier/L’Anse Fourmi/Speyside |

| 12 | Plymouth/Black Rock |

| 13 | Roxborough/Argyle |

| 14 | Scarborough/Mt. Grace |

| 15 | Signal Hill/Patience Hill |

Demographics

The population was 60,874 at the 2011 census.[3] The capital, Scarborough, has a population of 17,537. While Trinidad is multiethnic, Tobago's population is primarily of African descent, with a growing proportion of Trinidadians of East Indian descent and Europeans. Between 2000 and 2011, the population of Tobago grew by 12.55 percent, making it one of the fastest-growing areas of Trinidad and Tobago.

Ancestry and ethnicity

| Racial composition | 2011[19] |

|---|---|

| Afro-Trinidadians and Tobagonians | 85.2% |

| Dougla (Indian and Black) | 4.2% |

| Multiracial | 4.2% |

| Indo-Trinidadians and Tobagonians | 2.5% |

| White Trinidadian/Tobagonian | 0.7% |

| Native American (Amerindian) | 0.1% |

| Chinese | 0.08% |

| Arab (Syrian/Lebanese) | 0.02% |

| Other | 0.1% |

| Not stated | 2.6% |

Religion

| Religious composition | 2011[19] |

|---|---|

| Seventh-day Adventism | 16.26% |

| Pentecostalism/Evangelicalism/Full Gospel | 14.69% |

| Anglicanism | 12.80% |

| Spiritual Baptist | 10.56% |

| Roman Catholicism | 6.64% |

| Methodism | 4.93% |

| Moravian | 4.56% |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 1.62% |

| Orisha-Shango | 1.52% |

| Hinduism | 0.67% |

| Baptists | 0.63% |

| Islam | 0.57% |

| Rastafari | 0.39% |

| Presbyterianism/Congregationalism | 0.18% |

| Other | 10.38% |

| Not Stated | 9.83% |

| None | 5.39% |

Economy

Trinidad and Tobago, a bird sanctuary

Tobago's main economy is based on tourism, fishing, and government spending, government spending being the largest. The local governing body, the Tobago House of Assembly (THA), employs 62% of the labor force.

Tourism is still a fledgling industry. Conventional beach and water-sports tourism is largely in the southwest around the airport and the coastal strip. Meanwhile, ecotourism is growing in significance, much of it focused on the large area of protected forest in the centre and north of the main island and on Little Tobago, a small island off the main island's northeast tip.

The southwestern tourist area around Crown Point, Store Bay, Buccoo Reef, and Pigeon Point has large expanses of sand and is dominated by resort-type developments. Tobago has many idyllic beaches along its coastline, especially those at Castara, Bloody Bay, and Englishman's Bay. Tobago is linked to the world through the Arthur Napoleon Raymond Robinson International Airport (formerly Crown Point Airport) and Scarborough harbour. Domestic flights connect Tobago with Trinidad, and international flights connect with the Caribbean and Europe. There is a daily fast ferry service between Port of Spain and Scarborough.[citation needed]

Tobago's economy is tightly linked with Trinidad's, which is based on liquefied natural gas (LNG), petrochemicals, and steel.

Diving

Tobago is also a popular diving location, since it is the southernmost of the Caribbean islands that have coral communities. Trinidad, which is further south, has no significant coral because of low salinity and high silt content, the result of its position close to the mouth of Venezuela's Orinoco River. Scuba diving on Tobago tends to be centred at Speyside, almost diametrically across the island from the airport. [citation needed]

The island has some of the best diving sites in the Caribbean. There are three wrecks located around its shores, but the one usually considered the best is the Maverick Ferry, which used to travel between Trinidad and Tobago. The ferry is 350 feet (110 metres) long and has been sunk in 30 metres (98 feet) just off Rocky Point, Mt. Irvine. The top of the wreck is at 15 metres (49 feet). The wreck has an abundance of marine life, including a 4-foot (1.2-metre) jewfish, a member of the grouper family. The wreck was purposely sunk for divers, and so all the doors and windows were removed. The waters around the island are home to many species of tropical fish, rays, sharks, and turtles.[20]

Golf

Tobago is home to two golf courses, both of which are open to visitors. The older of the two is Mount Irvine Hotel Golf Course, built in 1968. It was seen throughout the world after hosting the popular golf show "Shell's Wonderful World of Golf". The course is built amongst coconut palms and has a view of the Caribbean Sea from almost every hole. Formerly known as Tobago Plantations Golf Course, the recently renamed Magdalena Grand Hotel & Golf Club was opened in 2001 and has hosted the European Seniors Tour on three occasions. [citation needed]

In art

Robinson Crusoe

Tobago roughly matches the size and location of the island in Robinson Crusoe,[21][22] described as being located close to Trinidad and the mouth of Orinoco. However, the book is generally thought to be based on the experiences of Alexander Selkirk, who was marooned in the Pacific's Juan Fernández Islands, on the island later named after Robinson Crusoe. On Tobago, there is Crusoe Cave.

Swiss Family Robinson

In 1958, Tobago was chosen by the Walt Disney Company as the setting for a film based upon the Johann Wyss novel Swiss Family Robinson. When producers saw the island for the first time, they "fell instantly in love".[23][24] The script required animals, which were brought from all around the world, including eight dogs, two giant tortoises, forty monkeys, two elephants, six ostriches, four zebras, one hundred flamingos, six hyenas, two anacondas, and one tiger.[23]

Filming locations include Richmond Bay (the Robinsons beach), Mount Irvine Bay (the Pirates beach), and the Craig Hall Waterfalls. The treehouse was constructed in a 200-foot tall saman in the Goldsborough Bay area. After filming, locals convinced Disney, who had intended to remove all evidence of filmmaking, to let the treehouse remain, without interior furnishing. In 1960, the treehouse was listed for sale for $9,000, a fraction of its original cost, and became a popular attraction before the structure was destroyed by Hurricane Flora in 1963.[25] The tree still remains, however, and is located on the property of the Roberts Auto Service and Tyre Shop, located in Goldsborough, just off of Windward Road. A local Tobago resident says, "The tree has fallen into obscurity; only a few of the older people knew of its significance. As a matter of fact, not many people know of the film Swiss Family Robinson, much less that it was filmed here in Tobago."[26]

Ecology

The Tobago Forest Reserve (Main Ridge Reserve) is the oldest protected rain forest in the Western hemisphere and is biodiverse. It was designated a protected Crown reserve on 17 April 1776 after representations by Soame Jenyns, a Member of Parliament in Britain responsible for Tobago's development. It has remained a protected area since.[27][28]

This forested area has great biodiversity, including many species of birds (such as the dancing blue-backed manakin), mammals, frogs, (non-venomous) snakes, butterflies and other invertebrates.[27][28] Tobago also has nesting beaches for the leatherback turtle, which come to shore between April and July.[citation needed]

The island of Tobago has multiple coral reef ecosystems.[29][30] The Buccoo Reef, the Culloden Reef and Speyside Reef are the three largest coral reef marine ecosystems in Tobago.[31] These coral reef systems protect the shores of Tobago from eroding.[32]

Little Tobago, the small neighbouring island, supports some of the best dry forest remaining in Tobago. Little Tobago and St Giles Island are important seabird nesting colonies, with red-billed tropicbirds, magnificent frigatebirds and Audubon's shearwaters, among others.[33][34]

Environmental problems

Coral reefs have been damaged recently by silt and mud runoff during construction of a road along the northeast coast. There has also been damage to the reef in Charlotteville village caused by sealing the road at Flagstaff Hill and diverting more silty water down the stream from Flagstaff down to Charlotteville. [citation needed]

Notable Tobagonians

- The Mighty Shadow (Winston McGarland Bailey), singer

- Kelly-Ann Baptiste, Olympic sprinter

- Edwin Carrington, politician

- Tracy Davidson-Celestine, politician

- Winston Duke, actor

- Lalonde Gordon, Olympic sprinter

- Makan Hislop, Footballer

- Dominique Jackson, model and actress

- A. P. T. James, politician

- Buzz Johnson, publisher

- Renny Quow, Olympic sprinter

- Keith Rowley, politician

- A. N. R. Robinson, politician

- Calypso Rose (Linda Sandy-Lewis), singer

- Faith B. Yisrael, politician

- Dwight Yorke, footballer

References

- ^ "What Languages Are Spoken In Trinidad And Tobago?". WorldAtlas.com. August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ a b Trinidad and Tobago 2011 Population and Housing Census Demographic Report (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Central Statistical Office. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Trinidad and Tobago 2011 Population and Housing Census Demographic Report (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Central Statistical Office. p. 26. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Boomert, Arie (15 January 2016). The indigenous peoples of Trinidad and Tobago : from the first settlers until today. Leiden. ISBN 9789088903540. OCLC 944910446.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Reid, Basil (2004). "Reconstructing the Saladoid Religion of Trinidad and Tobago". The Journal of Caribbean History. 32: 243–278.

- ^ Learie, Luke B. (2007). Identity and secession in the Caribbean : Tobago versus Trinidad, 1889–1980. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press. ISBN 978-9766401993. OCLC 646844096.

- ^ Riddell (Author), Henri de Bourbon (comte de Chambord.), John. “The Patent of Baron to C Van Lampsins.” The Pedigree of the Duchess of Mantua, Montferrat and Ferrara, Oxford University, 1885, pp. 8–10.

- ^

Nimblett, Lennie M. (2012). Tobago: The Union with Trinidad 1889-1899. AuthorHouse. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9781477234501. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

1672: England declared war against the Netherlands and captured Tobago.

1673: The Dutch defeated the English in the third Anglo/Dutch war and occupied Tobago in May 1674 after the Peace of Westminster. - ^

Nimblett, Lennie M. (2012). Tobago: The Union with Trinidad 1889-1899. AuthorHouse. p. 12. ISBN 9781477234501. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

The island remained in dispute between Britain and France and was essentially a neutral island between 1679 and 1763. [...] Tobago [was] formally ceded by France to Britain at the Treaty of Paris 1763 after the Seven Years War.

- ^ Mahan, A.T. (1969). The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 167–168.

- ^ "45 years a Republic". Trinidad & Tobago Guardian. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Speed, R. C.; Smith-Horowitz, P. L. (1998). "The Tobago Terrane". International Geology Review. 40 (9): 805–830. Bibcode:1998IGRv...40..805S. doi:10.1080/00206819809465240. ISSN 0020-6814.

- ^ "Tobago (Great Tobago) [1551]". United Nations Earthwatch. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Anthony, Michael (2001). Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago. Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland, and London, UK. ISBN 0-8108-3173-2.

- ^ "Climate | Trinidad & Tobago Meteorological Service". www.metoffice.gov.tt. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Daily Summaries Station Details". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Staff (22 January 2009). "Ancil Dennis critiises THA". Trinidad and Tobago Live Online. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Electoral Districts in the Electoral Area of Tobago in relation to Tobago House of Assembly Elections, Elections & Boundaries Commission of T&T

- ^ a b Central Statistical Office. "NON-INSTITUTIONAL POPULATION BY SEX, AGE GROUP, ETHNIC GROUP AND MUNICIPALITY" (PDF).

- ^ "This page has been removed". The Guardian.

- ^ Rhead, Louis. LETTER TO THE EDITOR: "Tobago Robinson Crusoe's Island", The New York Times, 5 August 1899.

- ^ "Robinson Crusoe and Tobago", Island Guide

- ^ a b Passafiume, Andrea. "SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON (1960)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1995). The Disney Films : 3rd Edition. New York.: Hyperion Books. p. 176. ISBN 0-7868-8137-2.

- ^ "Some Really, Really Big Roots". Kevin Kidney. 27 March 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Swiss Family Tree Found". Kevin Kidney. 6 October 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b "The Main Ridge Forest Reserve". nationaltrust.tt. National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago.

- ^ a b "Tobago Main Ridge Forest Reserve". unesco.org. UNESCO.

- ^ Lapointe, Brian E.; Langton, Richard; Bedford, Bradley J.; Potts, Arthur C.; Day, Owen; Hu, Chuanmin (1 March 2010). "Land-based nutrient enrichment of the Buccoo Reef Complex and fringing coral reefs of Tobago, West Indies". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 60 (3): 334–343. Bibcode:2010MarPB..60..334L. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.10.020. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 20034641.

- ^ "Tobago's major tourist attraction..." www.guardian.co.tt. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Buglass, Salome; Donner, Simon D.; Alemu I, Jahson B. (15 March 2016). "A study on the recovery of Tobago's coral reefs following the 2010 mass bleaching event". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 104 (1): 198–206. Bibcode:2016MarPB.104..198B. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.038. hdl:2429/51752. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 26856646.

- ^ Burke, Lauretta Marie; Greenhalgh, Suzie; Prager, Daniel; Cooper, Emily. Coastal capital, Tobago : the economic contribution of Tobago's coral reefs. OCLC 919637127.

- ^ Gittens, Tyrell (11 July 2021). "Red-billed tropicbird, one of the laziest birds in Little Tobago". newsday.co.tt. Trinidad and Tobago Newsday.

- ^ Morris John, Ashleigh (13 December 2016). "Five Big Things About Our Little Tobago Adventure". nationaltrust.tt. National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago.

External links

- Tobago House of Assembly

- Tobago at worldstatesmen.org.