Friedrich List

Friedrich List | |

|---|---|

Lithography of List by Josef Kriehuber, 1845 | |

| Born | Daniel Friedrich List 6 August 1789 |

| Died | 30 November 1846 (aged 57) |

| Nationality | German |

| Academic career | |

| Field | Economics |

| School or tradition | Historical School |

| Influences | Jean-Antoine Chaptal · Alexander Hamilton · Daniel Raymond · Adolphe Thiers |

| Contributions | National innovation system Historical school of economics |

| Signature | |

Daniel Friedrich List (6 August 1789 – 30 November 1846) was a German entrepreneur, diplomat, economist and political theorist who developed the nationalist theory of political economy in both Europe and the United States.[1][2][3][4] He was a forefather of the German historical school of economics and argued for the Zollverein (a pan-German customs union) from a nationalist standpoint.[5] He advocated raising tariffs on imported goods while supporting free trade of domestic goods and stated the cost of a tariff should be seen as an investment in a nation's future productivity.[4] His theories and writing also influenced the American school of economics.

List was a political liberal[6] who collaborated with Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker on the Rotteck-Welckersches Staatslexikon, an encyclopedia of political science that advocated constitutional liberalism and which influenced the Vormärz.[7] At the time in Europe, liberal and nationalist ideas were almost inseparably linked, and political liberalism was not yet attached to what was later considered "economic liberalism."[6][8] Emmanuel Todd considers List a forerunner to John Maynard Keynes as a theorist of "moderate or regulated capitalism."[9]

Biography

Early life

Daniel Friedrich List was born in the free imperial city of Reutlingen in the Duchy of Württemberg. His date of birth is uncertain, but his baptism is usually given as August 6, 1789.[10] His father, Johannes (1746–1813), was a prosperous master tanner and a city official, and his mother was Maria Magdalena (née Schäfer). Daniel Friedrich was the second son and youngest child in his family.[11] He was educated at the town's Latin School. As an apprentice at his father's tanning business, List showed little interest in manual labor. He was apprenticed as a bureaucratic clerk at Blaubeuren.[11] After passing his examination, he entered the administrative service in 1805 and became Taxes and Warehouses Commissioner in Schelklingen.[11]

University professor and early advocacy for German customs union: 1817–1820

At age 23 in 1811, List was promoted to a post at Tübingen. While there, he regularly attended lectures at the University of Tübingen and expanded his reading. He also made the acquaintance of the future minister Johannes von Schlayer.[11] In 1816, List's position in the bureaucracy was improved as the succession of King William I of Württemberg ushered in a period of reform. Under minister Karl August von Wangenheim, later his sponsor, List rose quickly through the bureaucracy. He moved to the Ministry of Finance in Stuttgart and rose to the position of chief auditor and accountant in 1816. In that role, he commissioned surveys among emigrants from Baden and Württemberg for the purpose of studying the increase in emigration and enacting countermeasures.[12]

Von Wangenheim, who had meanwhile been appointed Minister for Church and School Affairs for the Duchy, commissioned List to propose reforms to university civil service training. List proposed establishing a political science faculty alongside the standard legal training, arguing in 1817:

"No one in our University has any conception of a national economy. No one teaches the science of agriculture, forestry, mining, industry, or trade. ... [T]he forms of government are in such a truly barbarous state, that if an official of the seventeenth century rose again from the dead he could at once take up his old work, though he would assuredly be astonished to find the advances that had been made during the interval in the simplest process of manufacture."[13]

This proposal was accepted and the institution opened in Tübingen on October 17, 1817. Despite lacking a university degree, List was appointed professor of public administration science at the insistence of Von Wangenheim. The established professors and the university committees opposed the appointment on the grounds that List had only achieved his position through patronage, and they accused him of incompetence.

List published his thoughts on these reform in the short book Die Staatskunde und Staatspraxis Württembergs (1818). He further published arguments for constitutional liberalism in the magazine Volksfreund aus Schwaben, a national newspaper for morality, freedom and law. His journalistic activities drew suspicion from the new Württemberg government, and List was compelled to submit a petition to the king to defend himself against accusations of subversion.

In 1819, List traveled to Frankfurt and organized local merchants to establish the General German Trade and Industry Association. This association, which was later renamed the "Association of German Merchants and Manufacturers", is considered the first German business association of the modern era. List thus stands at the beginning of the economic association system that has been typical of German economic history since the 19th century.[14] List formulated the association's opposition to customs borders between the various German states and first envisioned the creation of a large German common market as a necessary prerequisite for the industrialization of Germany.[15] With regard to the foreign trade policy of this desired new internal market, List advocated a retaliatory tariff that would compensate for the trade barriers that existed for German traders abroad. This tariff was intended to protect German economic interests, but it was not yet the idea of an educational tariff that he later developed.[16] The association initiated a petition drive and lobbied German governments and princes to promote these policies.

"Thirty-eight customs and toll lines in Germany paralyze internal traffic and produce approximately the same effect as if every limb of the human body were ligated so that the blood did not overflow into another. In order to trade from Hamburg to Austria, from Berlin to Switzerland, one has to cross ten states, study ten customs and toll regulations, and pay ten times the transit toll."

– Extract from the petition of the General German Trade and Industry Association of 14 April 1819 to the Federal Assembly, formulated by Friedrich List[17]

The Bundestag did not recognize the trade association and instead referred the signatories to the individual state governments. These, however, strictly rejected outside interference in state affairs, and List's activism lost the trust of King Wilhelm I. In order to forestall his dismissal as professor, List resigned his office.[18] Instead, List turned his focus to actiivsm. He became editor-in-chief of the newspaper Organ for the German Trade and Industry, founded on July 1, 1818 and managing director of the Trade and Industry Association. In the latter role, he traveled to various German capitals and unsuccessfully sought dialogue with the governments. Among other places, he traveled to Vienna in 1820, where a pan-German follow-up conference to the Carlsbad Assembly was held. There, List presented an expanded memorandum advocating for the broad principles of free trade. He also presented suggestions for an industrial exhibition or the establishment of an overseas trading company. Despite these failures, Wangenheim, who had become the Württemberg delegate to the Bundestag, relied on List to develop plans for a south German customs union, which eventually became a reality in 1828.

Member of Württemberg parliament and imprisonment: 1820–1824

By 1819, List had been elected to the Württemberg state parliament, but his election was invalid, having not reached the minimum age of 30. In 1820, he was elected to the state parliament from Reutlingen.

As a member of parliament, he continued his campaign for democracy and free trade. In his "Reutlingen Petition " of January 1821, he criticized the prevailing bureaucracy and economic policy, arguing, "A superficial look at the internal conditions of Württemberg must convince the unbiased observer that the legislation and administration of our fatherland suffer from fundamental defects that are consuming the marrow of the country and destroying civil liberties."[19] List further argued that Württemberg suffered under a “world of bureaucrats separated from the people, spread over the whole country and concentrated in the ministries, ignorant of the needs of the people and the conditions of civil life, … opposing every influence of the citizen as if it were a threat to the state.”[20] To remedy the issue, List proposed strong local self-government, including free elections to local authorities and independent local jurisdiction. However, his petition was confiscated by police before it could be distributed. Under pressure from King Wilhelm I, the conservative parliament withdrew his political immunity in a vote on February 24, 1821.[21]

On April 6, 1822, List was sentenced to ten months imprisonment at Hohenasperg.[22] He fled and evaded capture for two years in Baden, Alsace and Switzerland but returned to serve his sentence in 1824, having been unable to build a secure life in exile.

Exile in United States: 1825–1833

After serving five months of his sentence at Hohenasperg, List was pardoned in exchange for agreeing to emigrate to the United States of America. He initially worked as a farmer, with little success. After one year, he sold his farm and moved to Reading, Pennsylvania, where he became editor-in-chief of the German-language Reading Adler from 1826 to 1830.[23][24]

After discovering a coal deposit in 1827, he and several partners founded a coal mine. In 1831, they also founded the Little Schuylkill Navigation, Railroad and Coal Company, which opened a railroad line to transport the coal, making List an early American railroad pioneer.[23] Through these ventures, he gained a certain amount of wealth and financial independence, which he lost again in the wake of the Panic of 1837.

While in the United States, List further developed arguments for economic nationalism, joining American entrepreneurs in demanding the introduction of protective tariffs in 1827. List also came into contact with the ideas of Alexander Hamilton and contributed, among other works, to the 1827 publication Outlines of American Political Economy, in which he provided economic support for the demand for trade protections.[25] He began to distance himself from Adam Smith's theories of free trade as the basis for his customs union proposals, instead arguing that protective tariffs would empower the United States and Germany, which lagged behind England in industrialization, to develop domestic economic sovereignty. In Outlines of Political Economy, List drew heavily on Jean-Antoine Chaptal's work De l’industrie française (1819) and the emerging historical school of economics to argue that economic policy should vary depending on the needs of individual states.[24][26] Some argue (e.g., Chang, 2002) that List's American exile inspired his pronounced "National System", which found realization in Henry Clay's American System. Others deny this (e.g., Daastøl, 2011), since List argued for a German customs union as early as 1819 and his views in the United States were framed as pragmatic rather than dogmatic and were influenced by liberal protectionists such as Chaptal and Adolphe Thiers.[26]

The protectionist campaign brought List into the presidential election of 1828, in which he supported Andrew Jackson. Jackson granted List American citizenship in 1830 and appointed him consul to Hamburg in 1830, though this appointment was not confirmed by the United States Senate,[24] and the Grand Duchy of Baden at Leipzig in 1833, providing him diplomatic immunity and protection from prosecution in Württemberg. However, the position did not provide a fixed salary, and List soon neglected his duties. While in Leipzig, List traveled frequently to Paris to promote American-French trade relations. He met frequently with Heinrich Heine and, through his daughters, befriended the musicians Robert and Clara Schumann.

Leipzig, railway promotion and encyclopedist: 1833–1837

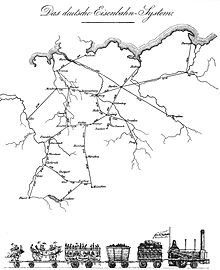

Soon after his arrival in Leipzig in 1833, List began to promote the construction of a greater German railway network. For List, overcoming the inner-German customs barriers and the construction of railways were the "Siamese twins" of German economic history and thus necessary steps towards the economic development of the German states.[27] He wrote a short paper, which he distributed free of charge in large numbers, arguing for the economic advantages of such a railway, which would enable cheap, fast and regular mass transport, and therefore promote the development of the division of labor, the choice of location for commercial enterprises and ultimately, a developed consumer economy. On the basis of this paper, a committee was founded that drew up a convincing cost and profitability analysis, negotiated the necessary concessions with the government and finally issued shares to finance the route. The Leipzig–Dresden railway, established in 1839, was the first German long-distance railway line. Most other German railway projects were also based on List's model of organization.[28]

He subsequently attempted to initiate similar projects in other German states or publicly supported existing projects. In 1835, for example, he advocated a route from Mannheim to Basel, another from Magdeburg to Berlin and a connection from there to Hamburg. In order to promote these proposals and his economic program, List founded the Eisenbahnjournal und National-Magazin für die Fortschritt in Handel, Gewerbe und Ackerbau in 1835. Forty issues of this magazine were published, concluding in 1837.

In Leipzig, List also proposed an encyclopedia of political science, the Rotteck-Welckersches Staatslexikon working with Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker as co-editors. Significant tensions quickly arose, particularly with Welcker, until List was pushed out of the project. The encyclopedia, published in 1834, is considered one of the most important texts of early German liberalism. It provided a common intellectual basis for the emerging German liberal movement and was therefore a significant contribution to its cohesion across the German states. Franz Schnabel described the first edition of 1834 as the "basic book of Vormärz liberalism."[29] List contributed articles focused on industry and technology, including railways, steamships, workers, wages and labor-saving machines.[30]

Despite his achievements, List himself received little material benefit from his involvement in railway politics, apart from a few bonuses. When his income from his American investments decreased following the Panic of 1837, List had to give up his voluntary activism and look for new ways of earning money. In addition, his attempt to be rehabilitated in Württemberg failed in 1836, after a corresponding petition for clemency had been rejected. List decided to relocate permanently to Paris.

Journalism and The National System: 1837–1841

In Paris, List wrote regularly for the leading German newspaper, Allgemeine Zeitung, as a correspondent on French domestic politics. He also returned to his work on general political economy. His 1837 work The Natural System of Political Economy renewed interest in his ideas in Germany, such that from 1839 to 1840, he was able to publish numerous essays on trade policy and legislation, which would later for the basis of his magnum opus.

In 1840, List returned to Germany following the death of his only son, Oskar, in the service of the French Foreign Legion. He settled in Augsburg, initially continuing his work as a journalist. In 1841, he published his main work, The National System of Political Economy, inspired by the work of Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, Histoire de l'economique politique en Europe.[31] As in his earlier writings, List argued that economic development was the product of legal, social and political factors and that industrialization was the necessary initial spark of a self-reinforcing process of development. Therefore, to promote industrialization, List advocated for the establishment of a unified nation-state and a protective tariff against foreign goods, until an internationally competitive domestic industry could be developed.[32]

List continued to promote his ideas in the German context, arguing that the liberal tariffs established by the Zollverein in 1834 had primarily promoted Prussian interests within Germany, and that the greater German economy should establish an "educational" tariff to counter the superior productivity of England. In 1844, the Zollverein set moderate protective tariffs focused on iron and yarn, stimulating economic development for a time but allowing technology transfers and the importation of necessary finished goods from England.[33][34]

Later years: 1841–1846

In 1841, the Württemberg government restored List's "civic honor", though his hopes of a position in the southern German states was not fulfilled. He continued to argue for protective tariffs, but became increasingly withdrawn due to ill health. In 1841, he declined an offer to edit the Rheinische Zeitung, a new liberal Cologne newspaper, and the role went to Gustav Höfken.[35] Karl Marx eventually took the post.[36] He also rejected an offer from Russian Minister of Finance Georg Ludwig Cancrin.[37]

In 1843, he established the Zollvereinsblatt in Augsburg, a newspaper in which continued his advocacy for the enlargement of the Zollverein and the organization of a national commercial system.[23] After a long lecture tour in 1844, he returned to Augsburg in 1845.[24] As the Zollverein moved toward a policy of free trade and List's ideas fell out of public interest, his publisher withdrew and he continued the Zollvereinsblatt at his own expense. He visited England with a view to forming a commercial alliance between that country and Germany but was unsuccessful.[23]

In 1846, with his property lost in another American crisis and his health failing, List traveled to Tyrol and committed suicide in Kufstein on November 30 with a seven-inch travel pistol.[4] Since the autopsy showed that List was "afflicted with such a degree of melancholy that free thought and action was impossible", he was afforded a Christian burial.[38]

In an obituary, List's long-time opponent Altvater[who?] wrote:

“It was List who stimulated a general sense of national economy in Germany, without which no nation can adequately shape its destiny.”

— Obituary in the Baltic Sea Stock Exchange News of January 1, 1847[39]

Views

Nationalist view of political economy

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

List's theory of "national economics" differed from the doctrines of "individual economics" and "cosmopolitan economics" by Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say. List argued that Smithian critiques of mercantilism were "partly correct", but argued for the need for temporary tariff protection targeted to protect specific infant industries that were critical to economic growth.[41]

List contrasted the economic behaviour of an individual with that of a nation.[41] An individual promotes only his own personal interests but a state fosters the welfare of all its citizens. An individual may prosper from activities which harm the interests of a nation. "Slavery may be a public calamity for a country, nevertheless some people may do very well in carrying on the slave trade and in holding slaves." Likewise, activities beneficial to society may injure the interests of certain individuals. "Canals and railroads may do great good to a nation, but all waggoners will complain of this improvement. Every new invention has some inconvenience for a number of individuals, and is nevertheless a public blessing". List argued that although some government action was essential to stimulate the economy, an overzealous government might do more harm than good. "It is bad policy to regulate everything and to promote everything by employing social powers, where things may better regulate themselves and can be better promoted by private exertions; but it is no less bad policy to let those things alone which can only be promoted by interfering social power."

Due to the "universal union" that nations have with their populace, List stated that "from this political union originates their commercial union, and it is in consequence of the perpetual peace thus maintained that commercial union has become so beneficial to them. ... The result of a general free trade would not be a universal republic, but, on the contrary, a universal subjection of the less advanced nations to the predominant manufacturing, commercial and naval power, is a conclusion for which the reasons are very strong. ... A universal republic ... , i.e. a union of the nations of the earth whereby they recognise the same conditions of right among themselves and renounce self-redress, can only be realised if a large number of nationalities attain to as nearly the same degree as possible of industry and civilisation, political cultivation and power. Only with the gradual formation of this union can free trade be developed; only as a result of this union can it confer on all nations the same great advantages which are now experienced by those provinces and states which are politically united. The system of protection, inasmuch as it forms the only means of placing those nations which are far behind in civilisation on equal terms with the one predominating nation, appears to be the most efficient means of furthering the final union of nations, and hence also of promoting true freedom of trade."[42]

In his seventh letter List repeated his assertion that economists should realise that since the human race is divided into independent states, "a nation would act unwisely to endeavour to promote the welfare of the whole human race at the expense of its particular strength, welfare, and independence. It is a dictate of the law of self-preservation to make its particular advancement in power and strength the first principles of its policy". A country should not count the cost of defending the overseas trade of its merchants. And "the manufacturing and agricultural interest must be promoted and protected even by sacrifices of the majority of the individuals, if it can be proved that the nation would never acquire the necessary perfection ... without such protective measures."[43]

List argued that international trade reduced the security of the states who took part in it.[44]

List argued that statesmen had two responsibilities: "one to contemporary society and one to future generations". Normally, the attention of most leaders is occupied by urgent matters, leaving little time to consider future problems. But when a country had reached a turning point in its development, its leaders were morally obliged to deal with issues that would affect the next generation. "On the threshold of a new phase in the development of their country, statesmen should be prepared to take the long view, despite the need to deal also with matters of immediate urgency."[45]

List's fundamental doctrine was that a nation's true wealth is the full and many-sided development of its productive power, rather than its current exchange values. For example, its economic education should be more important than immediate production of value, and it might be right that one generation should sacrifice its gain and enjoyment to secure the strength and skill of the future. Under normal conditions, an economically mature nation should also develop agriculture, manufacture and commerce. However, the last two factors were more important since they better influenced the nation's culture and independence and were especially connected to navigation, railways and high technology, and a purely-agricultural state tended to stagnate

However, List claimed that only countries in temperate regions were adapted to grow higher forms of industry. On the other hand, tropical regions had a natural monopoly in the production of certain raw materials. Thus, there were a spontaneous division of labor and a confederation of powers between both groups of countries.

List contended that Smith's economic system is not an industrial system but a mercantile system, and he called it "the exchange-value system". Contrary to Smith, he argued that the immediate private interest of individuals would not lead to the highest good of society. The nation stood between the individual and humanity, and was defined by its language, manners, historical development, culture and constitution. The unity must be the first condition of the security, well-being, progress and civilization of the individual. Private economic interests, like all others, must be subordinated to the maintenance, completion and strengthening of the nation.

Stages of economic development

List theorised that nations of the temperate zone (which are furnished with all the necessary conditions) naturally pass through stages of economic development in advancing to their normal economic state. These are:[citation needed]

- Pastoral life

- Agriculture

- Agriculture united with manufactures

- Agriculture, manufactures and commerce are combined

The progress of the nation through these stages is the task of the state, which must create the required conditions for the progress by using legislation and administrative action. This view leads to List's scheme of industrial politics. Every nation should begin with free trade, stimulating and improving its agriculture by trade with richer and more cultivated nations, importing foreign manufactures and exporting raw products. When it is economically so far advanced that it can manufacture for itself, then protection should be used to allow the home industries to develop, and save them from being overpowered by the competition of stronger foreign industries in the home market. When the national industries have grown strong enough that this competition is not a threat, then the highest stage of progress has been reached; free trade should again become the rule, and the nation be thus thoroughly incorporated with the universal industrial union. What a nation loses in exchange during the protective period, it more than gains in the long run in productive power. The temporary expenditure is analogous to the cost of the industrial education of the individual.[citation needed]

In a thousand cases the power of the State is compelled to impose restrictions on private industry. It prevents the ship owner from taking on board slaves on the west coast of Africa, and taking them over to America. It imposes regulations as to the building of steamers and the rules of navigation at sea, in order that passengers and sailors may not be sacrificed to the avarice and caprice of the captains. [...] Everywhere does the State consider it to be its duty to guard the public against danger and loss, as in the sale of the necessaries of life, so also in the sale of medicines, etc.[46]

Railways

List was the leading promoter of railways in Germany. His proposals on how to start up a system were widely adopted.[47] He summed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841:[48]

- It is a means of national defence: it facilitates the concentration, distribution and direction of the army.

- It is a means to the improvement of the culture of the nation. It brings talent, knowledge and skill of every kind readily to market.

- It secures the community against dearth and famine, and against excessive fluctuation in the prices of the necessaries of life.

- It promotes the spirit of the nation, as it has a tendency to destroy the Philistine spirit arising from isolation and provincial prejudice and vanity. It binds nations by ligaments, and promotes an interchange of food and of commodities, thus making it feel to be a unit. The iron rails become a nerve system, which, on the one hand, strengthens public opinion, and, on the other hand, strengthens the power of the state for police and governmental purposes.

List drew up proposals for a national railway network before the first steam locomotive ran between Nuremberg and Fürth. He suggested construction of a railway between Leipzig and Dresden which would soon become Germany's first long distance railway. He is honored for his early promotion of the importance of railways with a bust in Leipzig main station as well as several streets named after him adjacent to railway stations (e.g. Friedrich-List-Platz). When the Swiss-German architect de:Martin Mächler first proposed what is today Berlin main station in 1917, he suggested the new central interchange station of the German rail network be named in honor of List.

Britain and world trade

While List once had urged Germany to join other 'manufacturing nations of the second rank' to check Britain's 'insular supremacy', by 1841 he considered that the United States and Russia would become the most powerful countries[citation needed]—a view also expressed by Alexis de Tocqueville the previous year. List hoped to persuade political leaders in England to co-operate with Germany to ward off this danger. His proposal was perhaps not so far-fetched as might appear at first sight. In 1844, the writer of an article in a leading review had declared that 'in every point of view, whether politically or commercially, we can have no better alliance than that of the German nation, spreading as it does, its 42 millions of souls without interruption over the surface of central Europe'.[49]

The practical conclusion which List drew for Germany was that it needed for its economic progress an extended and conveniently bounded territory reaching to the seacoast both on north and south, and a vigorous expansion of manufacture and trade, and that the way to the latter lay through judicious protective legislation with a customs union comprising all German lands, and a German marine with a Navigation Act. The national German spirit, striving after independence and power through union, and the national industry, awaking from its lethargy and eager to recover lost ground, were favorable to the success of List's book, and it produced a great sensation. He ably represented the tendencies and demands of his time in his own country; his work had the effect of fixing the attention, not merely of the speculative and official classes, but of practical men generally, on questions of political economy; and his ideas were undoubtedly the economic foundation of modern Germany as applied by the practical genius of Bismarck.

List considered that Napoleon's 'Continental System', aimed just at damaging Britain during a bitter long-term war, had in fact been quite good for German industry. This was the direct opposite of what was believed by the followers of Adam Smith. As List put it:

I perceived that the popular theory took no account of nations, but simply of the entire human race on the one hand, or of the single individual on the other. I saw clearly that free competition between two nations which are highly civilised can only be mutually beneficial in case both of them are in a nearly equal position of industrial development, and that any nation which owing to misfortunes is behind others in industry, commerce, and navigation ... must first of all strengthen her own individual powers, in order to fit herself to enter into free competition with more advanced nations. In a word, I perceived the distinction between cosmopolitical and political economy.[50]

List's argument was that Germany should follow actual English practice rather than the abstractions of Smith's doctrines:

Had the English left everything to itself—'Laissez faire, laissez aller', as the popular economical school recommends—the [German] merchants of the Steelyard would be still carrying on their trade in London, the Belgians would be still manufacturing cloth for the English, England would have still continued to be the sheep-farm of the Hansards, just as Portugal became the vineyard of England, and has remained so till our days, owing to the stratagem of a cunning diplomatist. Indeed, it is more than probable that without her [highly protectionist] commercial policy England would never have attained to such a large measure of municipal and individual freedom as she now possesses, for such freedom is the daughter of industry and wealth.

Influences

List's hostility to free trade was first decisively shaped by the ideas of his friend Adolphe Thiers and other liberal protectionists in France.[26] He was also later influenced by Alexander Hamilton and the American School rooted in Hamilton's economic principles, including Daniel Raymond,[51] but also by the general mode of thinking of America's first Treasury Secretary, and by his strictures on the doctrine of Adam Smith. He opposed the cosmopolitan principle in the contemporary economical system and the absolute doctrine of free trade which was in harmony with that principle, and instead developed the infant industry argument, to which he had been exposed by Hamilton and Raymond.[51] He gave prominence to the national idea and insisted on the special requirements of each nation according to its circumstances and especially to the degree of its development. He famously doubted the sincerity of calls to free trade from developed nations, in particular Britain:

Any nation which by means of protective duties and restrictions on navigation has raised her manufacturing power and her navigation to such a degree of development that no other nation can sustain free competition with her, can do nothing wiser than to throw away these ladders of her greatness, to preach to other nations the benefits of free trade, and to declare in penitent tones that she has hitherto wandered in the paths of error, and has now for the first time succeeded in discovering the truth.[52]

His idea of productive powers was influenced by the philosophy of productivity of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.[53][54] He was acquainted with Robert Schumann and Heinrich Heine.[53]

Personal life

During his time as a professor in Tübingen, List married the widow Karoline Neidhard, daughter of the poet David Christoph Seybold and sister of the writer and editor Ludwig Georg Friedrich Seybold and Major General Johann Karl Christoph von Seybold (1777–1833) in Wertheim on February 19, 1818. List received permission from the ruler and dispensation from the University of Tübingen to marry in Baden.

List had three children:

- Emilie (born on December 10, 1818), who served as his secretary from 1833;

- Oskar (born on February 23, 1820);

- Elise (born July 1, 1822)[55] and

- Karoline, known as "Lina" (born January 20, 1829), who married history painter August Hövemeyer on March 5, 1855.[55]

Emilie List was a close friend of Clara Schumann following their meeting in Paris in 1833, and they exchanged letters for the remainder of their lives. Elise List was a singer who performed under Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and planned a concert tour with Franz Liszt which did not come to fruition.

Legacy

List's principal work is entitled Das Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie (1841) and was translated into English as The National System of Political Economy.

Before 1914, List and Marx were the two best-known German economists and theorists of development, although Marx, unlike List, devised no policies to promote economic development.

This book has been more frequently translated than the works of any other German economist, except Karl Marx.[56]

In Ireland he influenced Arthur Griffith of Sinn Féin and these theories were used by the Fianna Fáil government in the 1930s to instigate protectionism with a view to developing Irish industry.

Among others he strongly influenced was Sergei Witte, the Imperial Russian Minister of Finance, 1892–1903. Witte's plan for rapid industrialisation was centred around railroad construction (the Trans-Siberian railroad for example) and a policy of protectionism. At the time, it was largely considered that Russia was a backward country with an under developed economy. The boom which was seen during the 1890s was largely credited to Witte's policy.

Angus Maddison noted that:

As Marx was not interested in the survival of the capitalist system, he was not really concerned with economic policy, except in so far as the labour movement was involved. There, his argument was concentrated on measures to limit the length of the working day, and to strengthen trade union bargaining power. His analysis was also largely confined to the situation in the leading capitalist country of his day—the UK—and he did not consider the policy problems of other Western countries in catching up with the lead country (as Friedrich List did). In so far as Marx was concerned with other countries, it was mainly with poor countries which were victims of Western imperialism in the merchant capitalist era.[57]

Heterodox economists, such as South Korean Ha-Joon Chang and Norwegian Erik Reinert, refer to List often explicitly when writing about suitable economic policies for developing countries. List's influence among developing nations has been considerable. Japan has followed his model.[58]

The international economic policy of Meiji Japan was a combination of Hideyoshi's mercantilism and Friedrich List's Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie.[59]

It has also been argued that Deng Xiaoping's post-Mao policies were inspired by List, as well as recent policies in India.[60][61]

China, under Deng, took on the clear features of a 'developmental dictatorship under single-party auspices.' The PRC would then belong to a class of regimes familiar to the 20th century that have their ideological sources in classical Marxism, but better reflect the developmental, nationalist views of Friedrich List.[62]

A 1943 German film The Endless Road portrayed List's life and achievements. He was played by Eugen Klöpfer.

North Korea with its Juche ideology has likewise been considered by Dieter Senghaas to follow an "unequaled" model of development inspired by List's "production of productive forces."[63]

See also

- Economic interventionism

- Economic patriotism

- Henry Charles Carey

- Siegfried Moltke, a biographer of List's

- Caroline Märklin

Works in English translation

- —. The National System of Political Economy. Archived from the original on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

References

- ^ Freeman 1995.

- ^ Helleiner 2020.

- ^ Helleiner 2021.

- ^ a b c Friedrich List at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Tribe 2007, p. 36.

- ^ a b Hagemann & Wendler 2018, pp. 58–62.

- ^ Wendler 2014, pp. 12, 135–137.

- ^ Walther, Rudolf (1984). "Economic Liberalism". Economy and Society. 13 (2): 178–207. doi:10.1080/03085148300000019.

- ^ Wendler 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Hirst 1909, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Hirst 1909, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Friedrich Lists Auswanderungsbefragungen (1817) (Memento vom 27. September 2007 im Internet Archive), archived on January 3, 2013.

- ^ Hirst 1909, p. 8.

- ^ Friedrich Seidel, The Problem of Poverty in the German Vormärz according to Friedrich List. In: Cologne Lectures on Social and Economic History, issue 13, Cologne 1971, p. 3f.

- ^ Werner Lachmann: Entwicklungspolitik: Band 1: Grundlagen, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-25139-2, S. 128.

- ^ W. O. Henderson, Editor’s Introduction: Friedrich List: The Natural System of Political Economy. ISBN 0-7146-3206-6.

- ^ zitiert nach Hubert Kiesewetter: Industrielle Revolution in Deutschland: Regionen als Wachstumsmotoren. 2004, ISBN 3-515-08613-7, S. 31.

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. The Civil World and the Strong State. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X, p. 358.

- ^ quoted in Jörg Schweigard: The Höllenberg. In: Die Zeit, No. 43/2004.

- ^ quoted in Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. The Civil World and the Strong State. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X, p. 327.

- ^ Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List. In: Dictionary of the Social Sciences, Vol. 6. Stuttgart et. al. 1959, p. 634.

- ^ "GRIN - Friedrich List - Leben und Werk im Überblick".

- ^ a b c d Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ a b c d Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List. In: Dictionary of the Social Sciences, Vol. 6. Stuttgart et. al. 1959, p. 634.

- ^ a b c Todd 2015, pp. 15, 125, 146–153.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The Industrial Revolution in Germany. (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0, p. 22.

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. The Civil World and the Strong State. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X, p. 191.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: Liberalism in Germany. Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-11286-4, p. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Seidel, The Problem of Poverty in the German Vormärz according to Friedrich List. In: Cologne Lectures on Social and Economic History, issue 13, Cologne 1971, p. 12.

- ^ Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List. In: Dictionary of the Social Sciences, Vol. 6. Stuttgart et. al. 1959, p. 434.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The Industrial Revolution in Germany. (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0, p. 22.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The Industrial Revolution in Germany. (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0, p. 22f.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German Social History, Vol. 3, From the 'German Double Revolution' to the Beginning of the First World War: 1849–1914. 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-32263-1 , pp. 74–75.

- ^ Wilhelm Klutentreter: The Rheinische Zeitung of 1842/43. (Dortmund Contributions to Newspaper Research 10/1). Dortmund 1966, p. 56 f and p. 57 ff.

- ^ Henderson 1983, p. 85.

- ^ Heinz D. Kurz: Classics of Economic Thought. Vol. 1: From Adam Smith to Alfred Marschall. CHBeck Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57357-6, p. 164.

- ^ Arne Daniels: Brother, you have fallen into an evil time. In: Die Zeit. No. 32/1989.

- ^ Alfred E. Ott: Price Formation, Technical Progress and Economic Growth. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996, ISBN 3-525-13230-1, p. 244.

- ^ Originally published in 1841 at Stuttgart/Tübingen.

- ^ a b Helleiner, Eric (2023), Bukovansky, Mlada; Keene, Edward; Reus-Smit, Christian; Spanu, Maja (eds.), "Regulating Commerce", The Oxford Handbook of History and International Relations, Oxford University Press, pp. 334–C23P112, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198873457.013.22, ISBN 978-0-19-887345-7

- ^ National System of Political Economy, Friedrich List – p. 102–3

- ^ National System of Political Economy, Friedrich List—p. 150

- ^ Brooks 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ^ "The German Zollverein" in the Edinburgh Review, 1844, p. 117

- ^ Friedrich List. National System of Political Economy. p. 166.

- ^ Nipperdey 1996, p. 165.

- ^ List quoted in John J. Lalor, ed. Cyclopædia of Political Science (1881) 3:118

- ^ The German Zollverein in the Edinburgh Review, 1844, Vol. LXXIX, pp. 105 et seq.

- ^ The National System of Political Economy, by Friedrich List, 1841, translated by Sampson S. Lloyd M.P., 1885 edition, Author's Preface, Page xxvi.

- ^ a b Chang 2002.

- ^ The National System of Political Economy, by Friedrich List, 1841, translated by Sampson S. Lloyd M.P., 1885 edition, Fourth Book, "The Politics", Chapter 33.

- ^ a b Heuser 2008.

- ^ Heuser 1986.

- ^ a b Isabella Pfaff: Die Familie. In: Stadt Reutlingen Heimatmuseum und Stadtarchiv (Hrsg.): Friedrich List und seine Zeit: Nationalökonom, Eisenbahnpionier, Politiker, Publizist, 1789–1846: Katalog und Ausstellung zum 200. Geburtstag unter der Schirmherrschaft des Ministerpräsidenten Dr. h. c. Lothar Späth. Reutlingen 1989, ISBN 3-927228-19-2, S. 198 ff.

- ^ Henderson (1983)

- ^ Dynamic forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View, by Angus Maddison. Oxford University Press, 1991, page 19.

- ^ List's influence on Japanese economic policy: see "A contrary view: How the World Works Archived 2006-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, by James Fallows"

- ^ Linebarger, Chu & Burks 1954, p. 326.

- ^ Clairmonte 1959.

- ^ Boianovsky 2011, p. 2.

- ^ A. James Gregor, Précis No. 16, PS 137b - "Revolutionary Movements: Marxism and Fascism in East Asia" (Course Notes), 29 March 2005. Archived link, accessed 10 August 2014.

- ^ Juttka-Reisse, R. (1979.) Agrarpolitik und Kimilsungismus in der Demokratischen Volksrepublik Korea: Ein Beitrag zum Konzept autozentrierter Entwicklung. Hain: VIII—X.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "List, Friedrich". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

Books and book chapters

- Anonymous (1877). Fr. List, ein Vorlaufer und ein Opfer für das Vaterland [Friederich List: a Forerunner and a Sacrifice for the Fatherland]. Vol. II. Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Boianovsky, Mauro (2011). Friedrich List and the Economic Fate of Tropical Countries (PDF). Universidade de Brasilia. (dissertation)

- Bolsinger, Eckard (2004). The Foundation of Mercantile Realism: Friedrich List and International Political Economy (PDF). 54th Political Studies Association Annual Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-26.

- Brooks, Stephen G. (2005). Producing Security: Multinational Corporations, Globalization, and the Changing Calculus of Conflict. Vol. 102. Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7sjz7. ISBN 978-0-691-13031-6. JSTOR j.ctt7sjz7.

- Borchardt, Knut; Schötz, Hans Otto, eds. (1991). Wirtschaftspolitik in der Krise. Die (Geheim-)Konferenz der Friedrich List-Gesellschaft im Sept.1931 über Möglichkeiten und Folgen einer Kreditausweitung [Economic Policy in Crisis: The (Secret) Conference of the Friedrich List Society in September 1931 on the Possibilities and Consequences of Credit Expansion]. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Brügelmann, Hermann (1956). Politische Ökonomie in kritischen Jahren. Die Friedrich List-Gesellschaft E.V., von 1925-1935 [Political Economy in Critical Years: The Friedrich List Society from 1925-1935]. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Daastøl, Arno Mong (2011). Friedrich List's Heart, Wit and Will: Mental Capital as the Productive Force of Progress (PDF). Erfurt.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (doctoral dissertation) - Goldschmidt, Friedrich (1878). Friedrich List, Deutschlands grosser Volkswirth [Friedrich List, Germany's Greater National Economy] (in German). Berlin: J. Springer. OCLC 797286817.

- Hagemann, Harald; Wendler, Eugen (2018). The Economic Thought of Friedrich List. Routledge. pp. 58–62.

- Helleiner, Eric (2021). The Neomercantilists: A Global Intellectual History. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-6014-3.

- Henderson, William O. (1983). Friedrich List: Economist and Visionary, 1789–1846. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714631615.

- Hirst, Margaret E. (1909). Life of Friedrich List. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), containing a bibliography and a reprint of List's Petition on Behalf of the Handelsverein to the Federal Assembly (1819), Outlines of American Political Economy (1827), Philadelphia Speech (1827) (to the Harrisburg Convention), and the Introduction to The National System of Political Economy (1841). - Heuser, Marie-Luise (2008). "Romantik und Gesellschaft. Die Theorie der produktiven Kräfte" [Romance and Society: The Theory of Productive Forces]. In Gerhard, Myriam (ed.). Oldenburger Jahrbuch für Philosophie 2007 [Oldenburg Yearbook for Philosophy 2007]. pp. 253–277. ISBN 978-3-8142-2101-4.

- Heuser, Marie-Luise (1986). Die Produktivität der Natur. Schellings Naturphilosophie und das neue Paradigma der Selbstorganisation in den Naturwissenschaften. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. ISBN 3-428-06079-2.

- Jentsch, Carl (1901). Friedrich List (in German). Berlin: Ernst Hofmann and Co.

- Linebarger, Paul M. A.; Chu, Chu; Burks, Ardath W. (1954). Far Eastern Governments and Politics: China and Japan (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand.

- Nipperdey, Thomas (1996). Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck.

- Szporluk, Roman (1988). Communism and Nationalism: Karl Marx versus Friedrich List. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Thum, Gregor (2021). "Seapower and Frontier Settlement: Friedrich List's American Vision for Germany". In Lahti, Janne (ed.). German and United States Colonialism in a Connected World: Entangled Empires. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–39.

- Todd, David (2015). Free Trade and its Enemies in France, 1814–1851. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15, 125 & 146–153.

- Tribe, Keith (2007). Strategies of Economic Order. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521619431.

- Wendler, Eugen (2014). Friedrich List (1789-1846): A Visionary Economist with Social Responsibility. Springer.

Articles

- Chang, Ha-Joon (September 2002). "Kicking Away the Ladder: How the Economic and Intellectual Histories of Capitalism Have Been Re-Written to Justify Neo-Liberal Capitalism". Post-Autistic Economics Review (15).

- Clairmonte, Frederick (February 1959). "Friedrich List and the Historical Concept of Balance Growth". Indian Economic Review. 4 (3): 24–44.

- Ince, Onur Ulas (2016). "Friedrich List and the Imperial Origins of the National Economy". New Political Economy. 21 (4): 380–400. doi:10.1080/13563467.2016.1115827. S2CID 147126854.

- Freeman, C. (1995). "The National System of Innovation in Historical Perspective". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 19: 5–24.

- Helleiner, Eric (2020-11-23). "The Diversity of Economic Nationalism". New Political Economy. 26 (2): 229–238. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1841137. ISSN 1356-3467.

- Levi-Faur, David (1997). "Friedrich List and the Political Economy of the Nation-State". Review of International Political Economy. 4: 154–178. doi:10.1080/096922997347887.

- Levi-Faur, David (1997). "Economic Nationalism: From Friedrich List to Robert Reich". Review of International Studies. 23 (3): 359–370. doi:10.1017/S0260210597003598 (inactive 1 November 2024). S2CID 145497541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Notz, William (June 1926). "Frederick List in America". The American Economic Review. 16 (2). American Economic Association: 249–265. JSTOR 1805356.

- Selwyn, B. (2009). "An Historical Materialist Appraisal of Friedrich List and his Modern Day Followers". New Political Economy. 14 (2): 157–180. doi:10.1080/13563460902825965. S2CID 145702401.

External links

- A Comparison Of List, Marx and Adam Smith

- Quotations From List

- Wikiquote - Quotations From List

- Union Europe — List's vision of a peaceful union

- An unfinished review of The National System of Political Economy written by Karl Marx in 1845 Archived 2006-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Friedrich List in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW