The Frog Princess

| The Frog Princess | |

|---|---|

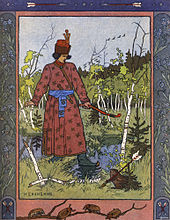

The Frog Tsarevna, Viktor Vasnetsov, 1918 | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Frog Princess |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 402 ("The Animal Bride") |

| Region | Eastern Europe |

| Published in | Russian Fairy Tales by Alexander Afanasyev |

| Related | |

The Frog Princess is a fairy tale that has multiple versions with various origins. It is classified as type 402, the animal bride, in the Aarne–Thompson index.[1] Another tale of this type is the Norwegian Doll i' the Grass.[2] Eastern European variants include the Frog Princess or Tsarevna Frog (Царевна Лягушка, Tsarevna Lyagushka)[3][4][5][6] and also Vasilisa the Wise (Василиса Премудрая, Vasilisa Premudraya); Alexander Afanasyev collected variants in his Narodnye russkie skazki, a collection which included folk tales from Ukraine and Belarus alongside Russian tales.[7]

"The Frog Princess" can be compared to the similar European fairy tale "The Frog Prince".

Synopsis

The king (or an old peasant woman, in Lang's version) wants his three sons to marry. To accomplish this, he creates a test to help them find brides. The king tells each prince to shoot an arrow. According to the King's rules, each prince will find his bride where the arrow lands. The youngest son's arrow is picked up by a frog. The king assigns his three prospective daughters-in-law various tasks, such as spinning cloth and baking bread. In every task, the frog far outperforms the two other lazy brides-to-be. In some versions, the frog uses magic to accomplish the tasks, and though the other brides attempt to emulate the frog, they cannot perform the magic. Still, the young prince is ashamed of his frog bride until she is magically transformed into a human princess.

In Calvino's version, the princes use slings rather than bows and arrows. In the Greek version, the princes set out to find their brides one by one; the older two are already married by the time the youngest prince starts his quest. Another variation involves the sons chopping down trees and heading in the direction pointed by them in order to find their brides.[8]

In the Russian versions of the story, Prince Ivan and his two older brothers shoot arrows in different directions to find brides. The other brothers' arrows land in the houses of the daughters of an aristocrat and a wealthy merchant, respectively. Ivan's arrow lands in the mouth of a frog in a swamp, who turns into a princess at night. The Frog Princess, named Vasilisa the Wise, is a beautiful, intelligent, friendly, skilled young woman, who was forced to spend three years in a frog's skin for disobeying Koschei. Her final test may be to dance at the king's banquet. The Frog Princess sheds her skin, and the prince then burns it, to her dismay. Had the prince been patient, the Frog Princess would have been freed but instead he loses her. He then sets out to find her again and meets with Baba Yaga, whom he impresses with his spirit, asking why she has not offered him hospitality. She tells him that Koschei is holding his bride captive and explains how to find the magic needle needed to rescue his bride. In another version, the prince's bride flies into Baba Yaga's hut as a bird. The prince catches her, she turns into a lizard, and he cannot hold on. Baba Yaga rebukes him and sends him to her sister, where he fails again. However, when he is sent to the third sister, he catches her and no transformations can break her free again.

In some versions of the story, the Frog Princess' transformation is a reward for her good nature. In one version, she is transformed by witches for their amusement. In yet another version, she is revealed to have been an enchanted princess all along.

Analysis

Tale type

The Eastern Europe tale is classified - and gives its name - to tale type SUS 402, "Russian: Царевна-лягушка, romanized: Tsarevna-lyagushka, lit. 'Princess-Frog'", of the East Slavic Folktale Catalogue (Russian: СУС, romanized: SUS).[9][7][4][5][6] According to Lev Barag, the East Slavic type 402 "frequently continues" as type 400: the hero burns the princess's animal skin and she disappears.[10]

Russian researcher Varvara Dobrovolskaya stated that type SUS 402, "Frog Tsarevna", figures among some of the popular tales of enchanted spouses in the Russian tale corpus.[11] In some Russian variants, as soon as the hero burns the skin of his wife, the Frog Tsarevna, she says she must depart to Koschei's realm,[12] prompting a quest for her (tale type ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife").[13] Jack Haney stated that the combination of types 402, "Animal Bride", and 400, "Quest for the Lost Wife", is a common combination in Russian tales.[14]

Species of animal bride

Dutch scholar Theo Meder supposed that the tale type originated in Europe, and the frog was the original form of the animal bride, although she can be a cat in Western Europe and a mouse in Northern Europe.[15] According to researcher Carole G. Silver and Yolando Pino-Saavedra, apart from bird and fish maidens, local forms of the animal bride include a frog in Burma, Russia, Austria and Italy; a dog in India and in North America; a mouse in Sri Lanka;[16] the frog, the toad and the monkey in Iberian Peninsula, and in Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking areas in the Americas.[17]

Professor Anna Angelopoulos noted that the animal wife in the Eastern Mediterranean is a turtle, which is the same animal of Greek variants.[18] In the same vein, Greek scholar Georgios A. Megas noted that similar aquatic beings (seals, sea urchin) and water-related entities (gorgonas, nymphs, neraidas) appear in the Greek oikotype of type 402.[19]

Role of the animal bride

The tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 402, "The Animal Bride". According to Andreas John, this tale type is considered to be a "male-centered" narrative. However, in East Slavic variants, the Frog Maiden assumes more of a protagonistic role along with her intended.[20] Likewise, scholar Maria Tatar describes the frog heroine as "resourceful, enterprising, and accomplished", whose amphibian skin is burned by her husband, and she has to depart to regions unknown. The story, then, delves into the husband's efforts to find his wife, ending with a happy reunion for the couple.[21]

On the other hand, Barbara Fass Leavy draws attention to the role of the frog wife in female tasks, like cooking and weaving. It is her exceptional domestic skills that impress her father-in-law and ensure her husband inherits the kingdom.[22]

Maxim Fomin sees "intricate meanings" in the objects the frog wife produces at her husband's request (a loaf of bread decorated with images of his father's realm; the carpet depicting the whole kingdom), which Fomin associated with "regal semantics".[23]

A totemic figure?

Analysing Armenian variants of the tale type where the frog appears as the bride, Armenian scholarship suggests that the frog bride is a totemic figure, and represents a magical disguise of mermaids and magical beings connected to rain and humidity.[24]

Likewise, Russian scholarship (e.g., Vladimir Propp and Yeleazar Meletinsky) has argued for the totemic character of the frog princess.[23] Propp, for instance, described her dance at the court as some sort of "ritual dance": she waves her arms and forests and lakes appear, and flocks of birds fly about.[25] Charles Fillingham Coxwell also associated these human-animal marriages to totem ancestry, and cited the Russian tale as one example of such.[26]

In his work about animal symbolism in Slavic culture, Russian philologist Aleksandr V. Gura stated that the frog and the toad are linked to female attributes, like magic and wisdom.[27] In addition, according to ethnologist Ljubinko Radenkovich, the frog and the toad represent liminal creatures that live between land and water realms, and are considered to be imbued with (often negative) magical properties in Slavic folklore.[28] In some variants, the Frog Princess is the daughter of Koschei, the Deathless,[23] and Baba Yaga - sorcerous characters with immense magical power who appear in Slavic folklore in adversarial position. This familial connection, then, seems to reinforce the magical, supernatural origin of the Frog Princess.[29]

Other motifs

Georgios A. Megas noted two distinctive introductory episodes: the shooting of arrows appears in Greek, Slavic, Turkish, Finnish, Arabic and Indian variants, while following the feathers is a Western European occurrence.[30]

Variants

Andrew Lang included an Italian variant of the tale, titled The Frog in The Violet Fairy Book.[31] Italo Calvino included another Italian variant from Piedmont, The Prince Who Married a Frog, in Italian Folktales,[32] where he noted that the tale was common throughout Europe.[33] Georgios A. Megas included a Greek variant, The Enchanted Lake, in Folktales of Greece.[34]

In a variant from northern Moldavia collected and published by Romanian author Elena Niculiță-Voronca, the bride selection contest replaces the feather and arrow for shooting bullets, and the frog bride commands the elements (the wind, the rain and the frost) to fulfill the three bridal tasks.[35]

Russia

The oldest attestation of the tale type in Russia is in a 1787 compilation of fairy tales, published by one Petr Timofeev.[36] In this tale, titled "Сказка девятая, о лягушке и богатыре" (English: "Tale nr. 9: About the frog and the bogatyr"), a widowed king has three sons, and urges them to find wives by shooting three arrows at random, and to marry whoever they find on the spot the arrows land on. The youngest son, Ivan Bogatyr, shoots his, and it takes him some time to find it again. He walks through a vast swamp and finds a large hut, with a large frog inside, holding his arrow. The frog presses Ivan to marry it, lest he will not leave the swamp. Ivan agrees, and it takes off the frog skin to become a beautiful maiden. Later, the king asks his daughters-in-law to weave him a fine linen shirt and a beautiful carpet with gold, silver and silk, and finally to bake him delicious bread. Ivan's frog wife summons the winds to help her in both sewing tasks. Lastly, the king invites his daughters-in-law to the palace, and the frog wife takes off the frog skin, leaves it at home and goes on a golden carriage. While she dances and impresses the court, Ivan goes back home and burns her frog skin. The maiden realizes her husband's folly and, saying her name is Vasilisa the Wise, tells him she will vanish to a distant kingdom and begs him to find her.[37]

Czech Republic

In a Czech variant translated by Jeremiah Curtin, The Mouse-Hole, and the Underground Kingdom, prince Yarmil and his brothers are to seek wives and bring to the king their presents in a year and a day. Yarmil and his brothers shoot arrow to decide their fates, Yarmil's falls into a mouse-hole. The prince enters the mouse hole, finds a splendid castle and an ugly toad he must bathe for a year and a day. When the date is through, he returns to his father with the toad's magnificent present: a casket with a small mirror inside. This repeats two more times: on the second year, Yarmil brings the princess's portrait and on the third year the princess herself. She reveals she was the toad, changed into amphibian form by an evil wizard, and that Yarmil helped her break this curse, on the condition that he must never reveal her cursed state to anyone, specially to his mother. He breaks this prohibition one night and she disappears. Yarmil, then, goes on a quest for her all the way to the glass mountain (tale type ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife").[38]

Ukraine

In a Ukrainian variant collected by M. Dragomanov, titled "Жена-жаба" ("The Frog Wife" or "The Frog Woman"), a king shoots three bullets to three different locations, the youngest son follows and finds a frog. He marries it and discovers it is a beautiful princess. After he burns the frog skin, she disappears, and the prince must seek her.[39]

In another Ukrainian variant, the Frog Princess is a maiden named Maria, daughter of the Sea Tsar and cursed into frog form. The tale begins much the same: the three arrows, the marriage between human prince and frog and the three tasks. When the human tsar announces a grand ball to which his sons and his wives are invited, Maria takes off her frog skin to appear as human. While she is in the tsar's ballroom, her husband hurries back home and burns the frog skin. When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo. The tale continues as tale type ATU 313, "The Magical Flight", like the Russian tale of The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise.[40]

Finland

Finnish author Eero Salmelainen collected a Finnish tale with the title Sammakko morsiamena (English: "The Frog Bride"), and translated into French as Le Cendrillon et sa fiancée, la grenouille ("The Male Cinderella and his bride, the frog"). In this tale, a king has three sons, the youngest named Tuhkimo (a male Cinderella; from Finnish tuhka, "ashes"). One day, the king organizes a bride selection test for his sons: they are to aim his bows and shoot arrows at random directions, and marry the woman that they will find with the arrow. Tuhkimo's arrow lands near a frog and he takes it as his bride. The king sets three tasks for his prospective daughters-in-law: to prepare the food and to sew garments. While prince Tuhkimo is asleep, his frog fiancée takes off her frog skin, becomes a human maiden and summons her eight sisters to her house: eight swans fly in through the window, take off their swanskins and become humans. Tuhkimo discovers his bride's transformation and burns the amphibian skin. The princess laments the fact, since her mother cursed her and her eight sisters, and in three nights time the curse would have been lifted. The princess then changes into a swan and flies away with her swan sisters. Tuhkimo follows her and meets an old widow, who directs him to a lake, in three days journey. Tuhkimo finds the lake, and he waits. Nine swans come, take off their skins to become human women and bathe in the lake. Tuhkimo hides his bride's swanskin. She comes out of the water and cannot find her swanskin. Tuhkimo appears to her and she tells him he must come to her father's palace and identify her among her sisters.[41][42]

Azerbaijan

In the Azerbaijani version of the fairy tale, the princes do not shoot arrows to choose their fiancées, they hit girls with apples.[43] And indeed, there was such a custom among the Mongols living in the territory of present-day Azerbaijan in the 17th century.[44]

Poland

In a Polish from Masuria collected by Max Toeppen with the title Die Froschprinzessin ("The Frog Princess"), a landlord has three sons, the elder two smart and the youngest, Hans (Janek in the Polish text), a fool. One day, the elder two decide to leave home to learn a trade and find wives, and their foolish little brother wants to do so. The two elders and Hans go their separate ways in a crossroads, and Hans loses his way in the woods, without food, and the berries of the forest not enough to sate his hunger. Luckily for him, he finds a hut in the distance, where a little frog lives. Hans tells the little animal he wants to find work, and the frog agrees to hire him, his only job is to carry the frog on a satin pillow, and he shall have drink and food. One day, the youth sighs that his brothers are probably returning home with gifts for their mother, and he has none to show them. The little frog tells Hans to sleep and, in the next morning, to knock three times on the stable door with a wand; he will find a beautiful horse he can ride home, and a little box. Hans goes back home with the horse and gives the little box to his mother; inside, a beautiful dress of gold and diamond buttons. Hans's brothers question the legitimate origin of the dress. Some time later, the brothers go back to their masters and promise to return with their brides. Hans goes back to the little frog's hut and mopes that his brother have bride to introduce to his family, while he has the frog. The frog tells him not to worry, and to knock on the stable again. Hans does that and a carriage appears with a princess inside, who is the frog herself. The princess asks Hans to take her to his parents, but not let her put anything on her mouth during dinner. Hans and the princess go to his parents' house, and he fulfills the princess's request, despite some grievaance from his parents and brothers. Finally, the princess turns back into a frog and tells Hans he has a last challenge before he redeems her: Hans will have to face three nights of temptations, dance, music and women in the first; counts and nobles who wish to crown him king in the second; and executioners who wish to kill him in the third. Hans endures and braves each night, awakening in the fourth day in a large castle. The princess, fully redeemed, tells him the castle is theirs, and she is his wife.[45]

In another Polish tale, collected by collector Antoni Józef Gliński and translated into English by translator Maude Ashurst Biggs as The Frog Princess, a king wishes to see his three sons married before they eventually ascend to the throne. So, the next day, the princes prepare to shoot three arrows at random, and to marry the girls that live wherever the arrows land. The first two find human wives, while the youngest's arrow falls in the margins of the lake. A frog, sat on it, agrees to return the prince's arrow, in exchange for becoming his wife. The prince questions the frog's decision, but she advises him to tell his family he married an Eastern lady who must be only seen by her beloved. Eventually, the king asks his sons to bring him carpet woven by his daughters-in-law. The little frog summons "seven lovely maidens" to help her weave the carpet. Next, the king asks for a cake to be baked by his daughters-in-law, and the little frog bakes a delicious cake for the king. Surprised by the frog's hidden talents, the prince asks her about them, and she reveals she is, in fact, a princess underneath the frog skin, a disguise created by her mother, the magical Queen of Light, to keep her safe from her enemies. The king then summons his sons and his daughters-in-law for a banquet at the palace. The little frog tells the prince to go first, and, when his father asks about her, it will begin to rain; when it lightens, he is to tell her she is adorning herself; and when it thunders, she is coming to the palace. It happens thus, and the prince introduces his bride to his father, and whispers in his ear about the frogskin. The king suggests his son burns the frogskin. The prince follows through with the suggestion and tells his bride about it. The princess cries bitter tears and, while he is asleep, turns into a duck and flies away. The prince wakes the next morning and begins a quest to find the kingdom of the Queen of Light. In his quest, he passes by the houses of three witches named Jandza, which spin on chicken legs. Each of the Jandzas tells him that the princess flies in their huts in duck form, and the prince must hide himself to get her back. He fails in the first two houses, due to her shapeshifting into other animals to escape, but gets her in the third. They reconcile and return to his father's kingdom.[46]

Other regions

Researchers Nora Marks Dauenhauer and Richard L. Dauenhauer found a variant titled Yuwaan Gagéets, heard during Nora's childhood from a Tlingit storyteller. They identified the tale as belonging to the tale type ATU 402 (and a second part as ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife") and noted its resemblance to the Russian story, trying to trace its appearance in the teller's repertoire.[47]

In a tale collected from a Surgut Khanty (Ostyak) source with the title The Frog Princess, a Torem khan is old and tells his three sons to find wives by casting arrows at random; wherever the arrows land on, they shall marry the girl. The three princes shoot their arrows and follow them: the elder finds his next to a merchant's house; the middle brother next to a lesser rich merchant, and the youngest in a marsh. He follows footprints and enters a grass-hut where he meets a talking frog who tells him to prepare for their wedding, for, when she comes, the earth will tremble and the skies will thunder, but he has nothing to fear. The three princess convene back in with their father, who asks his sons for their wives first to bring the best bread they can bake, and the best shirts they can weave. The Torem khan's daughters-in-law fulfill his requests, and he does approve of their efforts, but lauds the youngest's bride's work. Finally, the frog comes to the wedding just as she promised, and marries the youngest prince. One night, the wife of the khan wakes up and sees a bright light coming from her son's bedroom. She takes a peek inside and sees a beautiful maiden with the frogskin on her. Deciding to keep her human forever, the khan's wife mistakenly takes the frogskin and tosses it in the fire. The frog maiden vanishes soon after. The next morning, the third prince wakes up and, not seeing his wife, decides to leave home to look for her. He walks through the forest until he reaches "an iron road, a stone road", and follows the path, finally reaching an old woman's hut. The old woman welcomes him, and he tells her his issues. The woman then advises him to keep walking until he arrives at her middle sister's house, who may be able to help him. The prince goes to the next house, but the middle sister does not seem to be able to help him, so he sends him to her sister in a third hut. He reaches the third house, where the third old woman says the prince's wife will come in the next morning, so he should hide. The next morning, a swan flies in through the window and circumvents the hut. The prince comes out of hiding and wrestles with the swan to trap him in the house and not let it go. After a struggle, he manages to calm her down and takes her back with him to his kingdom, where they build an iron house for themselves. However, this draws the envy of his elder brother, who complains to Torem khan. The khan the summons his youngest son and sends him on quests for some of his grandfather's belongings in the lower world: first, for a "music-wood" (zither) and a "woman-wood" (violin); next, for a stick singing songs and a stick telling tales. The prince is helped by his wife, who gives him the means to enter the lower world (tale type ATU 465, "Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife").[48]

Adaptations

- A literary treatment of the tale was published as The Wise Princess (A Russian Tale) in The Blue Rose Fairy Book (1911), by Maurice Baring.[49]

- A translation of the story by illustrator Katherine Pyle was published with the title The Frog Princess (A Russian Story).[50]

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1939 Soviet film directed by Aleksandr Rou, is based on this plot. It was the first large-budget feature in the Soviet Union to use fantasy elements, as opposed to the realistic style long favored politically.[51]

- In 1953 the director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky had the idea of animating this popular national fairy tale. Production took two years, and the premiere took place in December, 1954. In 1996 this version of the tale was included in the film "Classic Fairy Tales From Around the World" on VHS. At present the film is included in the gold classics of "Soyuzmultfilm".

- Vasilisa the Beautiful, a 1977 Soviet animated film is also based on this fairy tale.

- Taking inspiration from the Russian story, Vasilisa appears to assist Hellboy against Koschei in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls.

- The Frog Princess was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, where it was depicted in a country setting. The episode features the voice talents of Jasmine Guy as Frog Princess Lylah, Greg Kinnear as Prince Gavin, Wallace Langham as Prince Bobby, Mary Gross as Elise, and Beau Bridges as King Big Daddy.

- A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title Marci és az elátkozott királylány ("Martin and the Cursed Princess").

- Wildwood Dancing, a 2007 fantasy novel by Juliet Marillier, expands the princess and the frog theme.[52]

Culture

Music

The Divine Comedy's 1997 single The Frog Princess is loosely based on the theme of the original Frog Princess story, interwoven with the narrator's personal experiences.

See also

References

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 224, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ D. L. Ashliman, "Animal Brides: folktales of Aarne–Thompson type 402 and related stories"

- ^

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource

Works related to The Frog-Tzarevna at Wikisource

- ^ a b Zheleznova, Irina (1985). Ukrainian Fairy Tales. Kyiv: Dnipro Publishers. pp. 104–115.

- ^ a b Oparenko, Christina (1996). Oxford Myths and Legends: Ukrainian Folk-tales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 125–142. ISBN 0192741683.

- ^ a b Suwyn, Barbara J. (1997). The Magic Egg and Other Tales from Ukraine. Englewood, Colorado: Libraries Unlimited, Inc. pp. 122–131. ISBN 1563084252.

- ^ a b Suwyn, Barbara J. (1997). The Magic Egg and Other Tales from Ukraine, Edited and with an Introduction by Natalie O. Kononenko. Englewood, Colorado: Libraries Unlimited, Inc. pp. xxi. ISBN 1563084252.

- ^ Out of the Everywhere: New Tales for Canada, Jan Andrews

- ^ Barag, Lev. "Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка". Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Barag, Lev. "Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка". Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. p. 128.

- ^ Dobrovolskaya, Varvara. "PLOT No. 425A OF COMPARATIVE INDEX OF PLOTS (“CUPID AND PSYCHE”) IN RUSSIAN FOLK-TALE TRADITION". In: Traditional culture. 2017. Vol. 18. № 3 (67). p. 139.

- ^ Johns, Andreas (16 January 2010). "The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore". Folklorica. 5 (1). doi:10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Kobayashi, Fumihiko (2007). "The Forbidden Love in Nature. Analysis of the "Animal Wife" Folktale in Terms of Content Level, Structural Level, and Semantic Level". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 36: 141–152. doi:10.7592/FEJF2007.36.kobayashi.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. (2015). The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. University Press of Mississippi. p. 548. ISBN 978-1-4968-0278-1. Project MUSE book 42506.

- ^ Meder, Theo. "Dier als bruid". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. p. 93.

- ^ Silver, Carole G. "Animal Brides and Grooms: Marriage of Person to Animal Motif B600, and Animal Paramour, Motif B610". In: Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (eds.). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. A Handbook. Armonk / London: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. p. 94.

- ^ Pino Saavedra, Yolando. Folktales of Chile. [Chicago:] University of Chicago Press, 1967. p. 258.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna (2005). "La fille de Thalassa". Estudos de Literatura Oral (11/12): 17–32.

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Broskou, Aigle. "ΕΠΕΞΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ ΠΑΡΑΜΥΘΙΑΚΩΝ ΤΥΠΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΡΑΛΛΑΓΩΝ AT 300-499". Tome B: AT 400-499. Athens, Greece: ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΝΕΟΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ Ε.Ι.Ε. 1999. p. 540.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism. Norton Critical Edition. Norton, 1999. p. 31. ISBN 9780393972771

- ^ Leavy, Barbara Fass (1994). "The Animal Bride". In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender. NYU Press. pp. 196–244. ISBN 978-0-8147-5068-1. JSTOR j.ctt9qg995.9.

- ^ a b c Fomin, Maxim (2010). "The Land Acquisition Motif in the Irish and Russian Folklore Traditions". Studia Celto-Slavica. 3: 251–279. doi:10.54586/HXAR3954. S2CID 54545201.

- ^ Hayrapetyan, Thamar (2020). "Combinaisons archétypales dans les épopées orales et les contes merveilleux arméniens". Revue des Études Arméniennes. 39: 471–591. doi:10.2143/REA.39.0.3288979.

- ^ Propp, V. Theory and history of folklore. Theory and history of literature v. 5. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. p. 143. ISBN 0-8166-1180-7.

- ^ Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 252.

- ^ Гура, Александр Викторович. "Символика животных в славянской народной традиции" [Animal Symbolism in Slavic folk traditions]. М: Индрик, 1997. pp. 380-382. ISBN 5-85759-056-6.

- ^ Radenkovic, Ljubinko. "Митолошки елементи у словенским народним представама о жаби" [Mythological Elements in Slavic Notions of Frogs]. In: Заједничко у словенском фолклору: зборник радова [Common Elements in Slavic Folklore: Collected Papers, 2012]. Београд: Балканолошки институт САНУ, 2012. pp. 379-397. ISBN 978-86-7179-074-1.

- ^ Kovalchuk Lidia Petrovna (2015). "Comparative research of blends frog-woman and toad-woman in Russian and English folktales". In: Russian Linguistic Bulletin, (3 (3)), 14-15. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/comparative-research-of-blends-frog-woman-and-toad-woman-in-russian-and-english-folktales (дата обращения: 17.11.2021).

- ^ Megas, Geōrgios A. Folktales of Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970. p. 224.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Violet Fairy Book, "The Frog"

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 438 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 718 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, p 49, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Ciubotaru, Silvia. "Elena Niculiţă-Voronca şi basmele fantastice" [Elena Niculiţă-Voronca and the Fantastic Fairy Tales]. In: Anuarul Muzeului Etnografic al Moldovei [The Yearly Review of the Ethnographic Museum of Moldavia] 18/2018. p. 158. ISSN 1583-6819.

- ^ Barag, Lev. "Сравнительный указатель сюжетов. Восточнославянская сказка". Leningrad: НАУКА, 1979. pp. 46 (source), 128 (entry).

- ^ Русские сказки в ранних записях и публикациях». Л.: Наука, 1971. pp. 203-213.

- ^ Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. pp. 331–355.

- ^ Драгоманов, М (M. Dragomanov)."Малорусские народные предания и рассказы". 1876. pp. 313-317.

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 179-181. ISBN 9781576070635.

- ^ Salmelainen, Eero. Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita. II Osa. Helsingissä: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. 1871. pp. 118–127.

- ^ Beauvois, Eugéne. Contes populaires de la Norvège, de la Finlande & de la Bourgogne, etc. Paris: E. Dentu, Éditeur. 1862. pp. 180–193.

- ^ "Царевич и лягушка". Фольклор Азербайджана и прилегающих стран. Vol. 1. Баку: Изд-во АзГНИИ. 1930. pp. 30–33.

- ^ Челеби Э. (1983). "Описание крепости Шеки/О жизни племени ит-тиль". Книга путешествия. (Извлечения из сочинения турецкого путешественника ХVII века). Вып. 3. Земли Закавказья и сопредельных областей Малой Азии и Ирана. Москва: Наука. p. 159.

- ^ Toeppen, Max. Aberglauben aus Masuren, mit einem Anhange, enthaltend: Masurische Sagen und Mährchen. Danzig: Th. Bertling, 1867. pp. 158-162.

- ^ Polish Fairy Tales. Translated from A. J. Glinski by Maude Ashurst Biggs. New York: John Lane Company. 1920. pp. 1-15.

- ^ Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Dauenhauer, Richard L. "Tracking “Yuwaan Gagéets”: A Russian Fairy Tale in Tlingit Oral Tradition". In: Oral Tradition, 13/1 (1998): 58-91.

- ^ CSEPREGI, Márta (1997). "Samples of the Genres of Ostyak Folklore". Acta Ethnographica Hungarica. 42 (3–4): 338–345.

- ^ Baring, Maurice. The Blue Rose Fairy Book. New York: Maude, Dodd and Company. 1911. pp. 247-260.

- ^ Pyle, Katherine. Tales of folk and fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1919. pp. 137-158.

- ^ James Graham, Baba Yaga in Film[usurped]

- ^ "Wildwood Dancing (Wildwood, #1)".