Taiji (philosophy)

| Taiji | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 太極 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Supreme pole/goal" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thái cực | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 太極 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 태극 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 太極 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 太極 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | たいきょく | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

In Chinese philosophy, taiji (Chinese: 太極; pinyin: tàijí; Wade–Giles: tʻai chi; trans. "supreme ultimate") is a cosmological state of the universe and its affairs on all levels, including the mutually reinforcing interactions between the two opposing forces of yin and yang, (a dualistic monism),[1][2] as well as that among the Three Treasures, the four cardinal directions, and the Five Elements—which together ultimately bring about the myriad things, each with their own nature. The taiji concept has reappeared throughout the technological, religious, and philosophical history of the Sinosphere, finding concrete application in techniques developed in acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine.

Etymology

Taiji (太極) is a compound of tai (太 'great', 'supreme') and ji (極 'pole', 'extremity'). Used together, taiji may be understood as 'source of the world'. Common English translations of taiji in the cosmological sense include "Supreme Ultimate",[3] "Supreme Pole",[4] and "Great Absolute".[5]

Core concept

Scholars Zhang and Ryden explain the ontological necessity of taiji.

Any philosophy that asserts two elements such as the yin-yang of Chinese philosophy will also look for a term to reconcile the two, to ensure that both belong to the same sphere of discourse. The term 'supreme ultimate' performs this role in the philosophy of the Book of Changes. In the Song dynasty it became a metaphysical term on a par with the Way.[6]

Taiji is understood to be the highest conceivable principle from which existence flows. This is very similar to the Daoist idea "reversal is the movement of the Dao". The "supreme ultimate" creates yang and yin. Movement generates yang, and when its activity reaches its limit, it becomes tranquil. Through tranquility the supreme ultimate generates yin. When tranquility has reached its limit, there is a return to movement. Movement and tranquility, in alternation, become each the source of the other. The distinction between the yin and yang is determined and the two forms (that is, the yin and yang) stand revealed. By the transformations of the yang and the union of the yin, the 4 directions then the 5 phases (wuxing) of wood, fire, earth, metal and water.

Taiji is, ometal ond then water. larity, revealing opposing features as in expanding/contracting, rising/falling, clockwise/ anticlockwise. However, taiji has sometimes been thought of as a monistic concept similar to wuji, as in the Wujitu diagram.[7] Wuji literally translates as "without roof pole", but means without limit, polarity, and/or opposite. Compared with wuji, taiji describes movement and change wherein limits do arise. While wuji is undifferentiated, timeless, absolute, infinite potential, taiji is often wrongly portrayed as conflictual, differentiated and dualistic, where as the core to this philosophy is their harmonious, relative and complementary natures.

Yin and yang are reflections and originate from wuji to become taiji.

In Chinese texts

Zhuangzi

The Daoist classic Zhuangzi introduced the taiji concept. One of the (ca. 3rd century BCE) "Inner Chapters" contrasts taiji (here translated as "zenith") with the liuji (六極). Liuji literally means "six ultimates; six cardinal directions", but here it is translated as "nadir".

The Way has attributes and evidence, but it has no action and no form. It may be transmitted but cannot be received. It may be apprehended but cannot be seen. From the root, from the stock, before there was heaven or earth, for all eternity truly has it existed. It inspirits demons and gods, gives birth to heaven and earth. It lies above the zenith but is not high; it lies beneath the nadir but is not deep. It is prior to heaven and earth, but is not ancient; it is senior to high antiquity, but it is not old.[8]

Huainanzi

The 2nd century BCE Huainanzi mentions a zhenren ("true person; perfected person") and the taiji that transcends categories like yin and yang, exemplified with the fusui and fangzhu mirrors.

The fu-sui 夫煫 (burning mirror) gathers fire energy from the sun; the fang-chu 方諸 (moon mirror) gathers dew from the moon. What are [contained] between Heaven and Earth, even an expert calculator cannot compute their number. Thus, though the hand can handle and examine extremely small things, it cannot lay hold of the brightness [of the sun and moon]. Were it within the grasp of one's hand (within one's power) to gather [things within] one category from the Supreme Ultimate (t'ai-chi 太極) above, one could immediately produce both fire and water. This is because Yin and Yang share a common ch'i and move each other.[9]

I Ching

Taiji also appears in the Xici, a commentary to the I Ching. It is traditionally attributed to Confucius but more likely dates to about the 3rd century BCE.[10]

Therefore there is in the Changes the Great Primal Beginning. This generates the two primary forces. The two primary forces generate the four images. The four images generate the eight trigrams. The eight trigrams determine good fortune and misfortune. Good fortune and misfortune create the great field of action.[11]

This sequence of powers of two includes taiji → yin and yang (two polarities) → Sixiang (Four Symbols) → Bagua (eight trigrams).

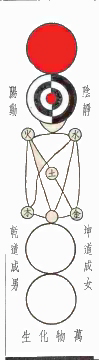

The fundamental postulate is the "great primal beginning" of all that exists, t'ai chi – in its original meaning, the "ridgepole". Later Indian philosophers devoted much thought to this idea of a primal beginning. A still earlier beginning, wu chi, was represented by the symbol of a circle. Under this conception, t'ai chi was represented by the circle divided into the light and the dark, yang and yin,

. This symbol has also played a significant part in India and Europe. However, speculations of a Gnostic-dualistic character are foreign to the original thought of the I Ching; what it posits is simply the ridgepole, the line. With this line, which in itself represents oneness, duality comes into the world, for the line at the same time posits an above and a below, a right and left, front and back – in a word, the world of the opposites.[12]

Song dynasty

In the Neo-Confucianism philosophy that developed during the Song dynasty, taiji was viewed "as a microcosm equivalent to the structure of the human body."[13] The Song-era philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073 CE) wrote the Taijitushuo (太極圖說) "Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate", which became the cornerstone of Neo-Confucianist cosmology. Zhou's brief text synthesized aspects of Chinese Buddhism and Daoism with the metaphysical discussions in the I Ching. Zhou's opening lines are:

Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)![a] The Supreme Polarity[b] in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established. The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.[15]

In tai chi

The martial art tai chi draws heavily on Chinese philosophy, especially the concept of the taiji. The Chinese name of tai chi, taijiquan, literally translates as "taiji boxing" or "taiji fist".[16] Early tai chi masters such as Yang Luchan promoted the connection between their martial art and the concept of the taiji.[17][18][19][20] The twenty-fourth chapter of the "Forty Chapter" tai chi classic that Yang Banhou gave to Wu Quanyou says the following about the connect between tai chi and spirituality:

If the essence of material substances lies in their phenomenological reality, then the presence of the ontological status of abstract objects shall become clear in the final culmination of the energy that is derived from oneness and the Real. How can man learn this truth? By truly seeking that which is the shadow of philosophy and the charge of all living substances, that of the nature of the divine. [citation needed]

See also

- Bagua

- National and regional symbols which contain the Taiji mark

- Flag of Mongolia

- Flag of Tibet

- Taegeuk – Sino-Korean pronunciation for Taiji

- Taijitu

- Tomoe

- Absolute (philosophy)

- Ohr

Notes

- ^ Alternatively, this line could be translated as "The Supreme Polarity that is Non-Polar!"

- ^ Instead of usual taiji translations "Supreme Ultimate" or "Supreme Pole", Adler uses "Supreme Polarity" [14] because Zhu Xi describes it as the alternating principle of yin and yang, and "... insists that taiji is not a thing (hence "Supreme Pole" will not do). Thus, for both Zhou and Zhu, taiji is the yin-yang principle of bipolarity, which is the most fundamental ordering principle, the cosmic "first principle." Wuji as "non-polar" follows from this."

References

Citations

- ^ Japanese Kampo Medicines for the Treatment of Common Diseases. Elsevier Science. 2017. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-128-09444-0.

- ^ Chang, Chi-yun (2013). Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation. World Scientific. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-9-814-43989-3.

- ^ Le Blanc 1985, Zhang & Ryden 2002

- ^ Needham & Ronan 1978

- ^ Adler 1999

- ^ Zhang & Ryden 2002, p. 179

- ^ Wang, Robin R. (July 2005). "Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained: A Construction of the Confucian Metaphysics". Journal of the History of Ideas. 66 (3). Loyola Marymount University: 311. doi:10.1353/jhi.2005.0047. S2CID 73700080 – via The Digital Scholarship Repository at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School.

- ^ Mair 1994, p. 55

- ^ Le Blanc 1985, pp. 120–1

- ^ Smith, Richard J. (2008). Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: The Yijing (I-Ching, or Classic of Changes) and Its Evolution in China. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 8.

- ^ Wilhelm & Baynes 1967, pp. 318–9

- ^ Wilhelm & Baynes 1967, p. lv

- ^ Oxtoby, Willard Gurdon, ed. (2002). World Religions: Eastern Traditions (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 424. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

- ^ See Robinet 1990

- ^ Adler 1999, pp. 673–4

- ^ Michael P. Garofalo (2021). "Thirteen Postures of Taijiquan". Cloud Hands blog. Archived from the original on 2023-04-16. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-415-00228-1.

- ^ Woolidge, Doug (June 1997). "T'AI CHI The International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan Vol. 21 No. 3". T'ai Chi. Wayfarer Publications. ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (2007). "Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion - Journal of Asian Martial Arts Vol. 16 No. 4". Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Publishing. ISSN 1057-8358.

Sources

- Adler, Joseph A. (1999). "Zhou Dunyi: The Metaphysics and Practice of Sagehood". In De Bary, William Theodore; Bloom, Irene (eds.). Sources of Chinese Tradition (2nd ed.). Columbia University Press.

- Bowker, John (2002). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Religions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521810371.

- Cohen, Kenneth J. (1997). The Way of QiGong. The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 9780345421098.

- Coogan, Michael, ed. (2005). Eastern Religions: origins, beliefs, practices, holy texts, sacred places. Oxford University press. ISBN 9780195221916.

- Chen, Ellen M. (1989). The Tao Te Ching: A New Translation and Commentary. Paragon House. ISBN 9781557782380.

- Gedalecia, D. (October 1974). "Excursion Into Substance and Function: The Development of the T'i-Yung Paradigm in Chu Hsi". Philosophy East and West. 24 (4): 443–451. doi:10.2307/1397804. JSTOR 1397804.

- Le Blanc, Charles (1985). Huai-nan Tzu: Philosophical Synthesis in Early Han Thought: The Idea of Resonance (Kan-Ying) With a Translation and Analysis of Chapter Six. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622091795.

- Mair, Victor H. (1994). Wandering on the Way: early Taoist tales and parables of Chuang Tzu. Bantam. ISBN 9780824820381.

- National QiGong Association Research and Education Committee Meeting. Terminology Task Force. Meeting. November 2012.

- Needham, Joseph; Ronan, Colin A. (1978). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: an abridgement of Joseph Needham's original text. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 229421664.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1990). "The Place and Meaning of the Notion of Taiji in Taoist Sources Prior to the Ming Dynasty". History of Religions. 23 (4): 373–411. doi:10.1086/463205. S2CID 161955134.

- Robinet, Isabelle (2008). "Wuji and Taiji 無極 • 太極 Ultimateless and Great Ultimate". In Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. pp. 1057–9. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Wilhelm, Richard; Baynes, Cary F. (1967). The I Ching or Book of Changes. Bollingen Series XIX. Princeton University Press.

- Wu, Laurence C. (1986). Fundamentals of Chinese Philosophy. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-5570-5.

- Zhang, Dainian; Ryden, Edmund (2002). Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Yale University Press.