Varieties of Chinese

| Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinitic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographic distribution | China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-5 | zhx | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | sini1245 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

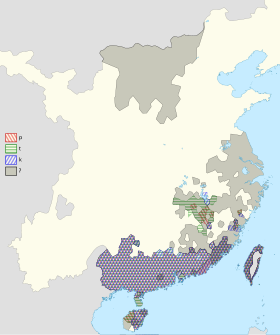

Primary branches of Chinese according to the Language Atlas of China.[3] The Mandarin area extends into Yunnan and Xinjiang (not shown). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hànyǔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

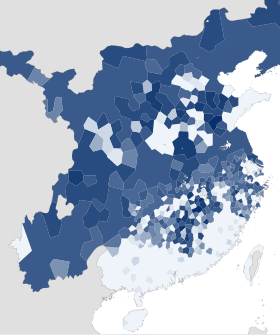

There are hundreds of local Chinese language varieties[b] forming a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast part of mainland China. The varieties are typically classified into several groups: Mandarin, Wu, Min, Xiang, Gan, Jin, Hakka and Yue, though some varieties remain unclassified. These groups are neither clades nor individual languages defined by mutual intelligibility, but reflect common phonological developments from Middle Chinese.

Chinese varieties have the greatest differences in their phonology, and to a lesser extent in vocabulary and syntax. Southern varieties tend to have fewer initial consonants than northern and central varieties, but more often preserve the Middle Chinese final consonants. All have phonemic tones, with northern varieties tending to have fewer distinctions than southern ones. Many have tone sandhi, with the most complex patterns in the coastal area from Zhejiang to eastern Guangdong.

Standard Chinese takes its phonology from the Beijing dialect, with vocabulary from the Mandarin group and grammar based on literature in the modern written vernacular. It is one of the official languages of China and one of the four official languages of Singapore. It has become a pluricentric language, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary between the three forms. It is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

History

At the end of the 2nd millennium BC, a form of Chinese was spoken in a compact area along the lower Wei River and middle Yellow River. Use of this language expanded eastwards across the North China Plain into Shandong, and then southwards into the Yangtze River valley and the hills of south China. Chinese eventually replaced many of the languages previously dominant in these areas, and forms of the language spoken in different regions began to diverge.[7] During periods of political unity there was a tendency for states to promote the use of a standard language across the territory they controlled, in order to facilitate communication between people from different regions.[8]

The first evidence of dialectal variation is found in the texts of the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC). Although the Zhou royal domain was no longer politically powerful, its speech still represented a model for communication across China.[7] The Fangyan (early 1st century AD) is devoted to differences in vocabulary between regions.[9] Commentaries from the Eastern Han (25–220 AD) provide significant evidence of local differences in pronunciation. The Qieyun, a rime dictionary published in 601, noted wide variations in pronunciation between regions, and was created with the goal of defining a standard system of pronunciation for reading the classics.[10] This standard is known as Middle Chinese, and is believed to be a diasystem, based on a compromise between the reading traditions of the northern and southern capitals.[11]

The North China Plain provided few barriers to migration, which resulted in relative linguistic homogeneity over a wide area. Contrastingly, the mountains and rivers of southern China contain all six of the other major Chinese dialect groups, with each in turn featuring great internal diversity, particularly in Fujian.[12][13]

Standard Chinese

Until the mid-20th century, most Chinese people spoke only their local language. As a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà (官話/官话 'officer speech'). While never formally defined, knowledge of this language was essential for a career in the imperial bureaucracy.[14]

In the early years of the Republic of China, Literary Chinese was replaced as the written standard by written vernacular Chinese, which was based on northern dialects. In the 1930s, a standard national language with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect was adopted, but with vocabulary drawn from a range of Mandarin varieties, and grammar based on literature in the modern written vernacular.[15] Standard Chinese is the official spoken language of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan, and is one of the official languages of Singapore.[16] It has become a pluricentric language, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary between the three forms.[17][18]

Standard Chinese is much more widely studied than any other variety of Chinese, and its use is now dominant in public life on the mainland.[19] Outside of China and Taiwan, the only varieties of Chinese commonly taught in university courses are Standard Chinese and Cantonese.[20]

Comparison with Romance

Local varieties from different areas of China are often mutually unintelligible, differing at least as much as different Romance languages and perhaps even as much as Indo-European languages as a whole.[21][22] As with the Romance languages descended from Latin, the ancestral language was spread by imperial expansion over substrate languages 2000 years ago, by the Qin and Han empires in China, and the Roman Empire in Europe. Medieval Latin remained the standard for scholarly and administrative writing in Western Europe for centuries, influencing local varieties much like Literary Chinese did in China. In both cases, local forms of speech diverged from both the literary standard and each other, producing dialect continua with mutually unintelligible varieties separated by long distances.[20][23]

However, a major difference between China and Western Europe is the historical reestablishment of political unity in 6th century China by the Sui dynasty, a unity that has persisted with relatively brief interludes until the present day. Meanwhile, Europe remained politically decentralized, and developed numerous independent states. Vernacular writing using the Latin alphabet supplanted Latin itself, and states eventually developed their own standard languages. In China, Literary Chinese was predominantly used in formal writing until the early 20th century. Written Chinese, read with different local pronunciations, continued to serve as a source of vocabulary for the local varieties. The new standard written vernacular Chinese, the counterpart of spoken Standard Chinese, is similarly used as a literary form by speakers of all varieties.[24][25]

Classification

Dialectologist Jerry Norman estimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese.[26] These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, although there are also some sharp boundaries.[27]

However, the rate of change in mutual intelligibility varies immensely depending on region. For example, the varieties of Mandarin spoken in all three northeastern Chinese provinces are mutually intelligible, but in the province of Fujian, where Min varieties predominate, the speech of neighbouring counties or even villages may be mutually unintelligible.[28]

Dialect groups

Classifications of Chinese varieties in the late 19th century and early 20th century were based on impressionistic criteria. They often followed river systems, which were historically the main routes of migration and communication in southern China.[30] The first scientific classifications, based primarily on the evolution of Middle Chinese voiced initials, were produced by Wang Li in 1936 and Li Fang-Kuei in 1937, with minor modifications by other linguists since.[31] The conventionally accepted set of seven dialect groups first appeared in the second edition (1980) of Yuan Jiahua's dialectology handbook:[32][33]

- Mandarin

- This is the group spoken in northern and southwestern China and has by far the most speakers. This group includes the Beijing dialect, which forms the basis for Standard Chinese, called Putonghua or Guoyu in Chinese, and often also translated as "Mandarin" or simply "Chinese". In addition, the Dungan language of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan is a Mandarin variety written in the Cyrillic script.

- Wu

- These varieties are spoken in Shanghai, most of Zhejiang and the southern parts of Jiangsu and Anhui. The group comprises hundreds of distinct spoken forms, many of which are not mutually intelligible. The Suzhou dialect is usually taken as representative, because Shanghainese features several atypical innovations.[34] Wu varieties are distinguished by their retention of voiced or murmured obstruent initials (stops, affricates and fricatives).[35]

- Gan

- These varieties are spoken in Jiangxi and neighbouring areas. The Nanchang dialect is taken as representative. In the past, Gan was viewed as closely related to Hakka because of the way Middle Chinese voiced initials became voiceless aspirated initials as in Hakka, and were hence called by the umbrella term "Hakka–Gan dialects".[36][37]

- Xiang

- The Xiang varieties are spoken in Hunan and southern Hubei. The New Xiang varieties, represented by the Changsha dialect, have been significantly influenced by Southwest Mandarin, whereas Old Xiang varieties, represented by the Shuangfeng dialect, retain features such as voiced initials.[38]

- Min

- These varieties originated in the mountainous terrain of Fujian and eastern Guangdong, and form the only branch of Chinese that cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese. It is also the most diverse, with many of the varieties used in neighbouring counties—and, in the mountains of western Fujian, even in adjacent villages—being mutually unintelligible.[28] Early classifications divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups, but a survey in the early 1960s found that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups.[39][40] Varieties from the coastal region around Xiamen have spread to Southeast Asia, where they are known as Hokkien (named from a dialectical pronunciation of "Fujian"), and Taiwan, where they are known as Taiwanese.[41] Other offshoots of Min are found in Hainan and the Leizhou Peninsula, with smaller communities throughout southern China.[40]

- Hakka

- The Hakka (literally "guest families") are a group of Han Chinese living in the hills of northeastern Guangdong, southwestern Fujian and many other parts of southern China, as well as Taiwan and parts of Southeast Asia such as Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Meixian dialect is the prestige form.[42] Most Hakka varieties retain the full complement of nasal endings, -m -n -ŋ and stop endings -p -t -k, though there is a tendency for Middle Chinese velar codas -ŋ and -k to yield dental codas -n and -t after front vowels.[43]

- Yue

- These varieties are spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong and Macau, and have been carried by immigrants to Southeast Asia and many other parts of the world. The prestige variety and by far most commonly spoken variety is Cantonese, from the city of Guangzhou (historically called "Canton"), which is also the native language of the majority in Hong Kong and Macau.[44] Taishanese, from the coastal area of Jiangmen southwest of Guangzhou, was historically the most common Yue variety among overseas communities in the West until the late 20th century.[45] Not all Yue varieties are mutually intelligible. Most Yue varieties retain the full complement of Middle Chinese word-final consonants (/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/) and have rich inventories of tones.[43]

The Language Atlas of China (1987) follows a classification of Li Rong, distinguishing three further groups:[46][47]

- Jin

- These varieties, spoken in Shanxi and adjacent areas, were formerly included in Mandarin. They are distinguished by their retention of the Middle Chinese entering tone category.[48]

- Huizhou

- The Hui dialects, spoken in southern Anhui, share different features with Wu, Gan and Mandarin, making them difficult to classify. Earlier scholars had assigned to them one or other of these groups, or to a group of their own.[49][50]

- Pinghua

- These varieties are descended from the speech of the earliest Chinese migrants to Guangxi, predating the later influx of Yue and Southwest Mandarin speakers. Some linguists treat them as a mixture of Yue and Xiang.[51]

Some varieties remain unclassified, including the Danzhou dialect (northwestern Hainan), Mai (southern Hainan), Waxiang (northwestern Hunan), Xiangnan Tuhua (southern Hunan), Shaozhou Tuhua (northern Guangdong), and the forms of Chinese spoken by the She people (She Chinese) and the Miao people.[52][53][54] She Chinese, Xiangnan Tuhua, Shaozhou Tuhua and unclassified varieties of southwest Jiangxi appear to be related to Hakka.[55][56]

Most of the vocabulary of the Bai language of Yunnan appears to be related to Chinese words, though many are clearly loans from the last few centuries. Some scholars have suggested that it represents a very early branching from Chinese, while others argue that it is a more distantly related Sino-Tibetan language overlaid with two millennia of loans.[57][58][59]

Dialect geography

Jerry Norman classified the traditional seven dialect groups into three zones: Northern (Mandarin), Central (Wu, Gan, and Xiang) and Southern (Hakka, Yue, and Min).[65] He argued that the dialects of the Southern zone are derived from a standard used in the Yangtze valley during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), which he called Old Southern Chinese, while the Central zone was a transitional area of dialects that were originally of southern type, but overlain with centuries of Northern influence.[65][61] Hilary Chappell proposed a refined model, dividing Norman's Northern zone into Northern and Southwestern areas, and his Southern zone into Southeastern (Min) and Far Southern (Yue and Hakka) areas, with Pinghua transitional between Southwestern and Far Southern areas.[66]

The long history of migration of peoples and interaction between speakers of different dialects makes it difficult to apply the tree model to Chinese.[67] Scholars account for the transitional nature of the central varieties in terms of wave models. Iwata argues that innovations have been transmitted from the north across the Huai River to the Lower Yangtze Mandarin area and from there southeast to the Wu area and westwards along the Yangtze River valley and thence to southwestern areas, leaving the hills of the southeast largely untouched.[68]

Some dialect boundaries, such as between Wu and Min, are particularly abrupt, while others, such as between Mandarin and Xiang or between Min and Hakka, are much less clearly defined.[27] Several east-west isoglosses run along the Huai and Yangtze Rivers.[69] A north-south barrier is formed by the Tianmu and Wuyi Mountains.[70]

Intelligibility testing

Most assessments of mutual intelligibility of varieties of Chinese in the literature are impressionistic.[71] Functional intelligibility testing is time-consuming in any language family, and usually not done when more than 10 varieties are to be compared.[72] However, one 2009 study aimed to measure intelligibility between 15 Chinese provinces. In each province, 15 university students were recruited as speakers and 15 older rural inhabitants recruited as listeners. The listeners were then tested on their comprehension of isolated words and of particular words in the context of sentences spoken by speakers from all 15 of the provinces surveyed.[73] The results demonstrated significant levels of unintelligibility between areas, even within the Mandarin group. In a few cases, listeners understood fewer than 70% of words spoken by speakers from the same province, indicating significant differences between urban and rural varieties. As expected from the wide use of Standard Chinese, speakers from Beijing were understood more than speakers from elsewhere.[74] The scores supported a primary division between northern groups (Mandarin and Jin) and all others, with Min as an identifiable branch.[75]

Terminology

Because speakers share a standard written form, and have a common cultural heritage with long periods of political unity, the varieties are popularly perceived among native speakers as variants of a single Chinese language,[76] and this is also the official position.[77] Conventional English-language usage in Chinese linguistics is to use dialect for the speech of a particular place (regardless of status), with regional groupings like Mandarin and Wu called dialect groups.[26] Other linguists choose to refer to the major groups as languages.[78] However, each of these groups contains mutually unintelligible varieties.[26] ISO 639-3 and the Ethnologue assign language codes to each of the top-level groups listed above except Min and Pinghua, whose subdivisions are assigned five and two codes respectively.[79] Some linguists refer to the local varieties as languages, numbering in the hundreds.[80]

The Chinese term fāngyán 方言, literally 'place speech', was the title of the first work of Chinese dialectology in the Han dynasty, and has had a range of meanings in the millennia since.[81] It is used for any regional subdivision of Chinese, from the speech of a village to major branches such as Mandarin and Wu.[82] Linguists writing in Chinese often qualify the term to distinguish different levels of classification.[83] All these terms have customarily been translated into English as dialect, a practice that has been criticized as confusing.[84] The neologisms regionalect and topolect have been proposed as alternative renderings of fāngyán.[84][c]

Phonology

The usual unit of analysis is the syllable, traditionally analysed as consisting of an initial consonant, a final and a tone.[86] In general, southern varieties have fewer initial consonants than northern and central varieties, but more often preserve the Middle Chinese final consonants.[87] Some varieties, such as Cantonese, Hokkien and Shanghainese, include syllabic nasals as independent syllables.[88]

Initials

In the 42 varieties surveyed in the Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects, the number of initials (including a zero initial) ranges from 15 in some southern dialects to a high of 35 in Chongming dialect, spoken in Chongming Island, Shanghai.[89]

| Fuzhou (Min) | Suzhou (Wu) | Beijing (Mandarin) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops and affricates |

voiceless aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | kʰ | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | tɕʰ | kʰ | pʰ | tʰ | tsʰ | tɕʰ | tʂʰ | kʰ | ||||||

| voiceless unaspirated | p | t | ts | k | p | t | ts | tɕ | k | p | t | ts | tɕ | tʂ | k | |||||||

| voiced | b | d | dʑ | ɡ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | s | x | f | s | ɕ | h | f | s | ɕ | ʂ | x | ||||||||||

| voiced | v | z | ʑ | ɦ | ɻ/ʐ | |||||||||||||||||

| Sonorants | l | ∅ | l | ∅ | l | ∅ | ||||||||||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | m | n | |||||||||||||

The initial system of the Fuzhou dialect of northern Fujian is a minimal example.[93] With the exception of /ŋ/, which is often merged with the zero initial, the initials of this dialect are present in all Chinese varieties, although several varieties do not distinguish /n/ from /l/. However, most varieties have additional initials, due to a combination of innovations and retention of distinctions from Middle Chinese:

- Most non-Min varieties have a labiodental fricative /f/, which developed from Middle Chinese bilabial stops in certain environments.[94]

- The voiced initials of Middle Chinese are retained in Wu dialects such as Suzhou and Shanghai, as well as Old Xiang dialects and a few Gan dialects, but have merged with voiceless initials elsewhere.[95][96] Southern Min varieties have an unrelated series of voiced initials resulting from devoicing of nasal initials in syllables without nasal finals.[97]

- The Middle Chinese retroflex initials are retained in many Mandarin dialects, including Beijing but not southwestern and southeastern Mandarin varieties.[98]

- In many northern and central varieties there is palatalization of dental affricates, velars (as in Suzhou), or both. In many places, including Beijing, palatalized dental affricates and palatalized velars have merged to form a new palatal series.[99]

- Maps of the distributions of various initial consonants in the core Chinese-speaking area

- voiced obstruent initials[100]

- retroflex initials[101]

- velar nasal initial (ŋ)[102]

- retained m- where Beijing has w-[103]

- retained n- where Beijing has r-[104]

Finals

Chinese finals may be analysed as an optional medial glide, a main vowel and an optional coda.[106]

Conservative vowel systems, such as those of Gan dialects, have high vowels /i/, /u/ and /y/, which also function as medials, mid vowels /e/ and /o/, and a low /a/-like vowel.[107] In other dialects, including Mandarin dialects, /o/ has merged with /a/, leaving a single mid vowel with a wide range of allophones.[108] Many dialects, particularly in northern and central China, have apical or retroflex vowels, which are syllabic fricatives derived from high vowels following sibilant initials.[109] In many Wu dialects, vowels and final glides have monophthongized, producing a rich inventory of vowels in open syllables.[110] Reduction of medials is common in Yue dialects.[111]

The Middle Chinese codas, consisting of glides /j/ and /w/, nasals /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/, and stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, are best preserved in southern dialects, particularly Yue dialects such as Cantonese.[43] In some Min dialects, nasals and stops following open vowels have shifted to nasalization and glottal stops respectively.[112] In Jin, Lower Yangtze Mandarin and Wu dialects, the stops have merged as a final glottal stop, while in most northern varieties they have disappeared.[113] In Mandarin dialects final /m/ has merged with /n/, while some central dialects have a single nasal coda, in some cases realized as a nasalization of the vowel.[114]

Tones

All varieties of Chinese, like neighbouring languages in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, have phonemic tones. Each syllable may be pronounced with between three and seven distinct pitch contours, denoting different morphemes. For example, the Beijing dialect distinguishes mā (妈/媽 'mother'), má (麻 'hemp'), mǎ (马/馬 'horse) and mà (骂/罵 'to scold'). The number of tonal contrasts varies between dialects, with Northern dialects tending to have fewer distinctions than Southern ones.[116] Many dialects have tone sandhi, in which the pitch contour of a syllable is affected by the tones of adjacent syllables in a compound word or phrase.[117] This process is so extensive in Shanghainese that the tone system is reduced to a pitch accent system much like modern Japanese.

The tonal categories of modern varieties can be related by considering their derivation from the four tones of Middle Chinese, though cognate tonal categories in different dialects are often realized as quite different pitch contours.[118] Middle Chinese had a three-way tonal contrast in syllables with vocalic or nasal endings. The traditional names of the tonal categories are 'level'/'even' (平 píng), 'rising' (上 shǎng) and 'departing'/'going' (去 qù). Syllables ending in a stop consonant /p/, /t/ or /k/ (checked syllables) had no tonal contrasts but were traditionally treated as a fourth tone category, 'entering' (入 rù), corresponding to syllables ending in nasals /m/, /n/, or /ŋ/.[119]

The tones of Middle Chinese, as well as similar systems in neighbouring languages, experienced a tone split conditioned by syllabic onsets. Syllables with voiced initials tended to be pronounced with a lower pitch, and by the late Tang dynasty, each of the tones had split into two registers conditioned by the initials, known as "upper" (阴/陰 yīn) and "lower" (阳/陽 yáng).[120] When voicing was lost in all dialects except in the Wu and Old Xiang groups, this distinction became phonemic, yielding eight tonal categories, with a six-way contrast in unchecked syllables and a two-way contrast in checked syllables.[121] Cantonese maintains these eight tonal categories and has developed an additional distinction in checked syllables.[122] (The latter distinction has disappeared again in many varieties.)

However, most Chinese varieties have reduced the number of tonal distinctions.[118] For example, in Mandarin, the tones resulting from the split of Middle Chinese rising and departing tones merged, leaving four tones. Furthermore, final stop consonants disappeared in most Mandarin dialects, and such syllables were distributed amongst the four remaining tones in a manner that is only partially predictable.[123]

| Middle Chinese tone and initial | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| level | rising | departing | entering | |||||||||||

| vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | vl. | n. | vd. | |||

| Jin[124] | Taiyuan | 1 ˩ | 3 ˥˧ | 5 ˥ | 7 ˨˩ | 8 ˥˦ | ||||||||

| Mandarin[124] | Xi'an | 1 ˧˩ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˦˨ | 5 ˥ | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Beijing | 1 ˥ | 2 ˧˥ | 3 ˨˩˦ | 5 ˥˩ | 1,2,3,5 | 5 | 2 | |||||||

| Chengdu | 1 ˦ | 2 ˧˩ | 3 ˥˧ | 5 ˩˧ | 2 | |||||||||

| Yangzhou | 1 ˨˩ | 2 ˧˥ | 3 ˧˩ | 5 ˥ | 7 ˦ | |||||||||

| Xiang[125] | Changsha | 1 ˧ | 2 ˩˧ | 3 ˦˩ | 6 | 5 ˥ | 6 ˨˩ | 7 ˨˦ | ||||||

| Shuangfeng | 1 ˦ | 2 ˨˧ | 3 ˨˩ | 6 | 5 ˧˥ | 6 ˧ | 2, 5 | |||||||

| Gan[126] | Nanchang | 1 ˦˨ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˨˩˧ | 6 | 5 ˦˥ | 6 ˨˩ | 7 ˥ | 8 ˨˩ | |||||

| Wu[127] | Suzhou | 1 ˦ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˦˩ | 6 | 5 ˥˩˧ | 6 ˧˩ | 7 ˦ | 8 ˨˧ | |||||

| Shanghai | 1 ˦˨ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˧˥ | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 ˥ | 8 ˨˧ | ||||||

| Wenzhou | 1 ˦ | 2 ˧˩ | 3 ˦˥ | 4 ˨˦ | 5 ˦˨ | 6 ˩ | 7 ˨˧ | 8 ˩˨ | ||||||

| Min[128] | Xiamen | 1 ˥ | 2 ˨˦ | 3 ˥˩ | 6 | 5 ˩ | 6 ˧ | 7 ˧˨ | 8 ˥ | |||||

| Hakka[129] | Meixian | 1 ˦ | 2 ˩˨ | 3 ˧˩ | 1,3 | 1 | 5 ˦˨ | 7 ˨˩ | 8 ˦ | |||||

| Yue[130] | Guangzhou | 1 ˥˧,˥ | 2 ˨˩ | 3 ˧˥ | 4 ˨˧[d] | 5 ˧ | 6 ˨ | 7a ˥ | 7b ˧ | 8 ˨ | ||||

In Wu, voiced obstruents were retained, and the tone split never became phonemic: the higher-pitched allophones occur with initial voiceless consonants, and the lower-pitched allophones occur with initial voiced consonants.[127] (Traditional Chinese classification nonetheless counts these as different tones.) Most Wu dialects retain the tone categories of Middle Chinese, but in Shanghainese several of these have merged.

Many Chinese varieties exhibit tone sandhi, in which the realization of a tone varies depending on the context of the syllable. For example, in Standard Chinese a third tone changes to a second tone when followed by another third tone.[132] Particularly complex sandhi patterns are found in Wu dialects and coastal Min dialects.[133] In Shanghainese, the tone of all syllables in a word is determined by the tone of the first, so that Shanghainese has word rather than syllable tone.

In northern varieties, many particles or suffixes are weakly stressed or atonic syllables. These are much rarer in southern varieties. Such syllables have a reduced pitch range that is determined by the preceding syllable.[134]

Vocabulary

Most morphemes in Chinese varieties are monosyllables descended from Old Chinese words, and have cognates in all varieties:

| Word | Jin | Mandarin | Xiang | Gan | Wu | Min | Hakka | Yue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiyuan | Xi'an | Beijing | Chengdu | Yangzhou | Changsha | Shuangfeng | Nanchang | Suzhou | Wenzhou | Fuzhou | Xiamen | Meixian | Guangzhou | |

| 人 'person' | zəŋ1 | ʐẽ2 | ʐən2 | zən2 | lən2 | ʐən2 | ɲiɛn2 | ɲin5 | ɲin2 | [f] | [f] | [f] | ɲin2 | jɐn2 |

| 男 'man' | næ̃1 | næ̃2 | nan2 | nan2 | liæ̃2 | lan2 | læ̃2 | lan5 | nø2 | nø2 | naŋ2 | lam2 | nam2 | nam2 |

| 女 'woman' | ny3 | mi3 | ny3 | ɲy3 | ly3 | ɲy3 | ɲy3 | ɲy3 | ɲy6 | ɲy4 | ny3 | lu3 | ŋ3 | nøy4 |

| 魚 'fish' | y1 | y2 | y2 | y2 | y2 | y2 | y2 | ɲiɛ5 | ŋ2 | ŋøy2 | ŋy2 | hi2 | ŋ2 | jy2 |

| 蛇 'snake' | sɤ1 | ʂɤ2 | ʂɤ2 | se2 | ɕɪ2 | sa2 | ɣio2 | sa5 | zo2 | zei2 | sie2 | tsua2 | sa2 | ʃɛ2 |

| 肉 'meat' | zuəʔ7 | ʐou5 | ʐou5 | zəu2 | ləʔ7 | ʐəu7 | ɲu5 | ɲiuk8 | ɲioʔ8 | ɲiəu8 | nyʔ8 | hɪk8 | ɲiuk7 | juk8 |

| 骨 'bone' | kuəʔ7 | ku1 | ku3 | ku2 | kuəʔ7 | ku7 | kəu2 | kut7 | kuɤʔ7 | ky7 | kauʔ7 | kut7 | kut7 | kuɐt7a |

| 眼 'eye' | nie3 | ɲiã3 | iɛn3 | iɛn3 | iæ̃3 | ŋan3 | ŋæ̃3 | ŋan3 | ŋɛ6 | ŋa4 | ŋiaŋ3 | gɪŋ3 | ɲian3 | ŋan4 |

| 耳 'ear' | ɚ3 | ɚ3 | ɚ3 | ɚ3 | a3 | ɤ3 | e3 | ə3 | ɲi6 | ŋ4 | ŋei5 | hi6 | ɲi3 | ji4 |

| 鼻 'nose' | pieʔ8 | pi2 | pi2 | pi2 | pieʔ7 | pi2 | bi6 | pʰit8 | bɤʔ8 | bei6 | pei6 | pʰi6 | pʰi5 | pei6 |

| 日 "sun", 'day' | zəʔ7 | ɚ1 | ʐʅ5 | zɿ2 | ləʔ7 | ɲʅ7 | i2 | ɲit8 | ɲɪʔ8 | ɲiai8 | niʔ8 | lit8 | ɲit7 | jat8 |

| 月 "moon", 'month' | yəʔ7 | ye1 | ye5 | ye2 | yəʔ7 | ye7 | ya5 | ɲyɔt8 | ŋɤʔ8 | ɲy8 | ŋuɔʔ8 | geʔ8 | ɲiat8 | jyt8 |

| 年 'year' | nie1 | ɲiæ̃2 | niɛn2 | ɲiɛn2 | liẽ2 | ɲiẽ2 | ɲɪ̃2 | ɲiɛn5 | ɲiɪ2 | ɲi2 | nieŋ2 | nĩ2 | ɲian2 | nin2 |

| 山 'mountain' | sæ̃1 | sæ̃1 | ʂan1 | san1 | sæ̃1 | san1 | sæ̃1 | san1 | sɛ1 | sa1 | saŋ1 | suã1 | san1 | ʃan1 |

| 水 'water' | suei3 | fei3 | ʂuei3 | suei3 | suəi3 | ɕyei3 | ɕy3 | sui3 | sɥ3 | sɿ3 | tsy3 | tsui3 | sui3 | ʃøy3 |

| 紅 'red' | xuŋ1 | xuoŋ2 | xuŋ2 | xoŋ2 | xoŋ2 | xən2 | ɣən2 | fuŋ5 | ɦoŋ2 | ɦoŋ2 | øyŋ2 | aŋ2 | fuŋ2 | huŋ2 |

| 綠 'green' | luəʔ7 | lou1 | ly5 | nu2 | lɔʔ7 | lou7 | ləu2 | liuk8 | loʔ7 | lo8 | luɔʔ8 | lɪk8 | liuk8 | luk8 |

| 黃 'yellow' | xuɒ̃1 | xuaŋ2 | xuaŋ2 | xuaŋ2 | xuɑŋ2 | uan2 | ɒŋ2 | uɔŋ5 | ɦuɒŋ2 | ɦuɔ2 | uɔŋ2 | hɔŋ2 | vɔŋ2 | wɔŋ2 |

| 白 'white' | piəʔ7 | pei2 | pai2 | pe2 | pɔʔ7 | pɤ7 | pia2 | pʰak7 | bɒʔ8 | ba8 | paʔ8 | peʔ8 | pʰak8 | pak8 |

| 黑 'black' | xəʔ7 | xei1 | xei1 | xe2 | xəʔ7 | xa7 | ɕia2 | hɛt8 | hɤʔ7 | xe7 | xaiʔ7 | hɪk7 | hɛt7 | hɐk7a |

| 上 'above' | sɒ̃5 | ʂaŋ5 | ʂaŋ5 | saŋ5 | sɑŋ5 | san6 | ɣiaŋ6 | sɔŋ6 | zɒŋ6 | ji6 | suɔŋ6 | tsiũ6 | sɔŋ5 | ʃœŋ6 |

| 下 'below' | ɕia5 | xa5 | ɕia5 | ɕia5 | xɑ5 | xa6 | ɣo6 | ha6 | ɦo6 | ɦo4 | a6 | e6 | ha2 | ha6 |

| 中 'middle' | tsuŋ1 | pfəŋ1 | tʂuŋ1 | tsoŋ1 | tsoŋ1 | tʂən1 | tan1 | tsuŋ1 | tsoŋ1 | tɕyoŋ1 | touŋ1 | taŋ1 | tuŋ1 | tʃuŋ1 |

| 大 'big' | ta5 | tuo5 | ta5 | ta5 | tai5 | tai6 | du6 | tʰɔ6 | dəu6 | dəu6 | tuai6 | tua6 | tʰai5 | tai6 |

| 小 'small' | ɕiau3 | ɕiau3 | ɕiau3 | ɕiau3 | ɕiɔ3 | ɕiau3 | ɕiɤ3 | ɕiɛu3 | siæ3 | sai3 | sieu3 | sio3 | siau3 | ʃiu3 |

Southern varieties also include distinctive substrata of vocabulary of non-Chinese origin. Some of these words may have come from Tai–Kadai and Austroasiatic languages.[137]

Grammar

Chinese varieties generally lack inflectional morphology and instead express grammatical categories using analytic means such as particles and prepositions.[138] There are major differences between northern and southern varieties, but often some northern areas share features found in the south, and vice versa.[139]

Constituent order

The usual unmarked word order in Chinese varieties is subject–verb–object, with other orders used for emphasis or contrast.[141] Modifiers usually precede the word they modify, so that adjectives precede nouns.[142] Instances in which the modifier follows the head are mainly found in the south, and are attributed to substrate influences from languages formerly dominant in the area, especially Kra–Dai languages.[143]

- Adverbs generally precede verbs, but in some southern varieties certain kinds of adverb follow the verb.[144]

- In the north, animal gender markers are prefixed to the noun, as in Beijing mǔjī (母鸡/母雞) 'hen' and gōngjī (公鸡/公雞) 'rooster', but most southern varieties use the reverse order, while others use different orders for different words.[145]

- Compounds consisting of an attributive following a noun are less common, but some are found in the south as well as a few northern areas.[146]

Nominals

Nouns in Chinese varieties are generally not marked for number.[139] As in languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, Chinese varieties require an intervening classifier when a noun is preceded by a demonstrative or numeral.[147] The inventory of classifiers tends to be larger in the south than in the north, where some varieties use only the general classifier cognate with ge 个/個.[148]

First- and second-person pronouns are cognate across all varieties. For third-person pronouns, Jin, Mandarin, and Xiang varieties have cognate forms, but other varieties generally use forms that originally had a velar or glottal initial:[149]

| Jin[135] | Mandarin[150] | Xiang[151] | Gan[152] | Wu[153] | Min[154] | Hakka[155] | Yue[156] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiyuan | Xi'an | Beijing | Chengdu | Yangzhou | Changsha | Shuangfeng | Nanchang | Suzhou | Wenzhou | Fuzhou | Xiamen | Meixian | Guangzhou | |

| 'I' | ɣɤ3 | ŋə3 | uo3 | ŋo3 | o3 | ŋo3 | aŋ3 | ŋɔ3 | ŋəu6 | ŋ4 | ŋuai3 | gua3 | ŋai2 | ŋo4 |

| 'you' | ni3 | ni3 | ni3 | ni3 | liɪ3 | n3, ɲi3 | n3 | li3, n3 | ne6 | ɲi4 | ny3 | li3 | ɲi2, n2 | nei4 |

| 'he/she' | tʰa1 | tʰa1 | tʰa1 | tʰa1 | tʰa1 | tʰa1 | tʰo1 | tɕʰiɛ3 | li1 | gi2 | i1 | i1 | ki2 | kʰøy4 |

Plural personal pronouns may be marked with a suffix, noun or phrase in different varieties. The suffix men 们/們 is common in the north, but several different suffixes are use elsewhere.[148] In some varieties, especially in the Wu area, different suffixes are used for first, second and third person pronouns.[157] Case is not marked, except in varieties in the Qinghai–Gansu sprachbund.[157]

The forms of demonstratives vary greatly, with few cognates between different areas.[158] A two-way distinction between proximal and distal is most common, but some varieties have a single neutral demonstrative, while others distinguish three or more on the basis of distance, visibility or other properties.[159] An extreme example is found in a variety spoken in Yongxin County, Jiangxi, where five grades of distance are distinguished.[160]

Attributive constructions typically have the form NP/VP + ATTR + NP, where the last noun phrase is the head and the attributive marker is usually a cognate of de 的 in the north or a classifier in the south.[161] The latter pattern is also common in the languages of Southeast Asia.[162] A few varieties in the Jiang–Huai, Wu, southern Min and Yue areas feature the old southern pattern of a zero attributive marker.[161] Nominalization of verb phrases or predicates is achieved by following them with a marker, usually the same as the attributive marker, though some varieties use a different marker.[163]

Major sentence types

All varieties have transitive and intransitive verbs. Instead of adjectives, Chinese varieties use stative verbs, which can function as predicates but differ from intransitive verbs in being modifiable by degree adverbs.[164] Ditransitive sentences vary, with northern varieties placing the indirect object before the direct object and southern varieties using the reverse order.[165]

All varieties have copular sentences of the form NP1 + COP + NP2, though the copula varies.[166] Most Yue and Hakka varieties use a form cognate with xì 係 'to connect'.[167] All other varieties use a form cognate with shì 是, which was a demonstrative in Classical Chinese but began to be used as a copula from the Han period.[168][169]

All varieties form existential sentences with a verb cognate with yǒu 有, which can also be used as a transitive verb indicating possession.[170] Most varieties use a locative verb cognate to zài 在, but Min, Wu and Yue varieties use several different forms.[171]

All varieties allow sentences of the form NP + VP1 + COMP + VP2, with a verbal complement VP2 containing a stative verb describing the manner or extent of the main verb.[172] In northern varieties, the marker is a cognate of de 得, but many southern varieties distinguish between manner and extent complements using different markers.[173] Standard Chinese does not allow an object to co-occur with a verbal complement, but other varieties permit an object between the marker and the complement.[174]

A characteristic feature of Chinese varieties is in situ questions:[175]

- Open questions are formed by replacing the desired information with an interrogative word, though the words vary between different areas.[176]

- Yes–no questions are formed by appending a particle to the sentence.

This particle is a cognate of ma 吗/嗎 in the north, but varies between other varieties.[177] Other question forms are also common:

- Most varieties have neutral questions employing the form V + NEG + V, repeating the same verb.[178] When the verb takes an object, some northwestern Mandarin varieties tend to place it after the first occurrence of the verb, while other Mandarin varieties and most southern varieties place it after the second occurrence.[179]

- Most varieties form disjunctive questions by placing a conjunction between the alternatives, though some also use particles to mark the disjuncts.[180] Standard Chinese is unusual in allowing a form with no conjunction.[177]

Verb phrases

A sentence is negated by placing a marker before the verb. Old Chinese had two families of negation markers starting with *p- and *m-, respectively.[181] Northern and Central varieties tend to use a word from the first family, cognate with Beijing bù 不, as the ordinary negator.[60] A word from the second family is used as an existential negator 'have not', as in Beijing méi 沒 and Shanghai m2.[182] In Mandarin varieties this word is also used for 'not yet', whereas in Wu and other groups a different form is typically used.[183] In Southern varieties, negators tend to come from the second family. The ordinary negators in these varieties are all derived from a syllabic nasal *m̩, though it has a level tone in Hakka and Yue and a rising tone in Min. Existential negators derive from a proto-form *mau, though again the tonal category varies between groups.[184]

Chinese varieties generally indicate the roles of nouns with respect to verbs using prepositions derived from grammaticalized verbs.[185][186] Varieties differ in the set of prepositions used, with northern varieties tending to use a substantially larger inventory, including disyllabic and trisyllabic prepositions.[187] In northern varieties, the preposition bǎ 把 may be used to move the object before the verb (the "disposal" construction).[188] Similar structures using several different prepositions are used in the south, but tend to be avoided in more colloquial speech.[189] Comparative constructions are expressed with a prepositional phrase before the stative verb in most northern and central varieties, as well as Northern Min and Hakka, while other southern varieties retain the older form in which the prepositional phrase follows the stative verb.[190] The preposition is usually bǐ 比 in the north, with other forms used elsewhere.[191]

Chinese varieties tend to indicate aspect using markers following the main verb.[192] The markers, usually derived from verbs, vary widely in both their forms and their degree of grammaticalization, from independent verbs, through complements to bound suffixes.[192] Southern varieties tend to have richer aspect systems making more distinctions than northern ones.[193]

Sociolinguistics

Bilingualism and code-switching

In southern China (not including Hong Kong and Macau), where the difference between Standard Chinese and local dialects is particularly pronounced, well-educated Chinese are generally fluent in Standard Chinese, and most people have at least a good passive knowledge of it, in addition to being native speakers of the local dialect. The choice of dialect varies based on the social situation. Standard Chinese is usually considered more formal and is required when speaking to a person who does not understand the local dialect. The local dialect (be it non-Standard Chinese or non-Mandarin altogether) is generally considered more intimate and is used among close family members and friends and in everyday conversation within the local area. Chinese speakers will frequently code switch between Standard Chinese and the local dialect. Parents will generally speak to their children in the local variety, and the relationship between dialect and Mandarin appears to be mostly stable, even a diglossia. Local dialects are valued as symbols of regional cultures.[194]

People generally are tied to the hometown and therefore the hometown dialect, instead of a broad linguistic classification. For example, a person from Wuxi may claim that he speaks Wuxi dialect, even though it is similar to Shanghainese (another Wu dialect). Likewise, a person from Xiaogan may claim that he speaks Xiaogan dialect. Linguistically, Xiaogan dialect is a dialect of Mandarin, but the pronunciation and diction are quite different from spoken Standard Chinese.

Knowing the local dialect is of considerable social benefit, and most Chinese who permanently move to a new area will attempt to pick up the local dialect. Learning a new dialect is usually done informally through a process of immersion and recognizing sound shifts. Generally the differences are more pronounced lexically than grammatically. Typically, a speaker of one dialect of Chinese will need about a year of immersion to understand the local dialect and about three to five years to become fluent in speaking it. Because of the variety of dialects spoken, there are usually few formal methods for learning a local dialect.

Due to the variety in Chinese speech, Mandarin speakers from each area of China are very often prone to fuse or "translate" words from their local language into their Mandarin conversations. In addition, each area of China has its recognizable accents while speaking Mandarin. Generally, the nationalized standard form of Mandarin pronunciation is only heard on news and radio broadcasts. Even in the streets of Beijing, the flavor of Mandarin varies in pronunciation from the Mandarin heard on the media.

In Taiwan, as most people at least understand, if not speak, Taiwanese Hokkien, Taiwanese Mandarin has acquired many loanwords from Hokkien. Some of these are directly implanted into Mandarin, as in the case of "蚵仔煎," "oyster omelet," which most Taiwanese people would call by its Hokkien name (ô-á-tsian) rather than its Mandarin one (é-zǐ-jiān). In other cases, Mandarin creates new words to imitate Hokkien ones, as in the case of "哇靠," ("damn") from the Hokkien "goák-hàu," but pronounced in Mandarin as "wā-kào."

While most Taiwanese people understand Hokkien, far fewer understand or speak Hakka, and Taiwanese Mandarin therefore contains fewer Hakka loanwords. Formerly, there was a misconception among linguists that language in Taiwan was primarily tied to ethnicity (i.e., Minnan people speak Hokkien, Hakka people speak Hakka, and Indigenous people speak the language corresponding to their tribe). Researchers later realized that, although it is true that most Minnan people speak Hokkien, most Hakka people also speak Hokkien and many of them do not speak Hakka. Hokkien remains the most prestigious language other than Mandarin and English in Taiwan. Although Hokkien, Hakka, and Taiwan's many Indigenous languages have now been elevated to the status of national languages, it is notable that there is a clear de facto gradient of valuation of these languages. For instance, on the Taipei metro when nearing the next station, a passenger will hear these languages in the following order: Mandarin, English, Hokkien, Hakka, sometimes followed by Japanese and Korean.

Language policy

Mainland China

Within mainland China, there has been a persistent Promotion of Putonghua drive; for instance, the education system is entirely Mandarin-medium from the second year onward. However, usage of local dialect is tolerated and socially preferred in many informal situations. In Hong Kong, written Cantonese is not used in formal documents, and within the PRC a character set closer to Mandarin tends to be used. At the national level, differences in dialect generally do not correspond to political divisions or categories, and this has for the most part prevented dialect from becoming the basis of identity politics.

Historically, many of the people who promoted Chinese nationalism were from southern China and did not natively speak Mandarin, and even leaders from northern China rarely spoke with the standard accent. For example, Mao Zedong often emphasized his origins in Hunan in speaking, rendering much of what he said incomprehensible to many Chinese.[citation needed] Chiang Kai-shek and Sun Yat-sen were also from southern China, and this is reflected in their conventional English names reflecting Cantonese pronunciations for their given names, and differing from their pinyin spellings Jiǎng Jièshí and Sūn Yìxiān. One consequence of this is that China does not have a well-developed tradition of spoken political rhetoric, and most Chinese political works are intended primarily as written works rather than spoken works. Another factor that limits the political implications of dialect is that it is very common within an extended family for different people to know and use different dialects.

Taiwan

Before 1945, most of the population of Taiwan were Han Chinese, some of whom spoke Japanese, in addition to Taiwanese Hokkien or Hakka, with a minority of Taiwanese aborigines, who spoke Formosan languages.[195] When the Kuomintang retreated to the island after losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, they brought a substantial influx of speakers of Northern Chinese (and other dialects from across China), and viewed the use of Mandarin as part of their claim to be a legitimate government of the whole of China.[196] Education policy promoted the use of Mandarin over the local languages, and was implemented especially rigidly in elementary schools, with punishments and public humiliation for children using other languages at school.[196]

From the 1970s, the government promoted adult education in Mandarin, required Mandarin for official purposes, and encouraged its increased use in broadcasting.[197] Over a 40-year period, these policies succeeded in spreading the use and prestige of Mandarin through society at the expense of the other languages.[198] They also aggravated social divisions, as Mandarin speakers found it difficult to find jobs in private companies but were favored for government positions.[198] From the 1990s, Taiwanese languages (Taiwanese Hokkien, Taiwanese Hakka and the Formosan languages) were offered in elementary and middle schools, first in Yilan county, then in other areas governed by elected Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) politicians, and finally throughout the island.[199]

Singapore

In 1966, the Singaporean government implemented a policy of bilingual education, where Singaporean students learn both English and their designated native language, which was Mandarin for Chinese Singaporeans (even though Singaporean Hokkien had previously been their lingua franca). The Goh Report, an evaluation of Singapore's education system by Goh Keng Swee, showed that less than 40% of the student population managed to attain minimum levels of competency in two languages.[200] It was later determined that the learning of Mandarin among Singaporean Chinese was hindered by home use of other Chinese varieties, such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, and Hakka.[201][202] Hence, the government decided to rectify problems facing implementation of the bilingual education policy, by launching a campaign to promote Mandarin as a common language among the Chinese population, and to discourage use of other Chinese varieties.

Launched in 1979 by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew,[203] the campaign aimed to simplify the language environment for Chinese Singaporeans, improve communication between them, and create a Mandarin-speaking environment conducive to the successful implementation of the bilingual education program. The initial goal of the campaign was for all young Chinese to stop speaking dialects in five years, and to establish Mandarin as the language of choice in public places within 10 years.[204][205] According to the government, for the bilingual policy to be effective, Mandarin should be spoken at home and should serve as the lingua franca among Chinese Singaporeans.[206] They also argued that Mandarin was more economically valuable, and speaking Mandarin would help Chinese Singaporeans retain their heritage, as Mandarin contains a cultural repository of values and traditions that are identifiable to all Chinese, regardless of dialect group.[207]

See also

- Languages of China

- List of varieties of Chinese

- Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects

- Protection of the Varieties of Chinese

Notes

- ^ The colloquial layers of many varieties, particularly Min varieties, reflect features that predate Middle Chinese.[1][2]

- ^ Also known as the Sinitic languages, from Late Latin Sīnae, "the Chinese". In 1982, Paul K. Benedict proposed a subgroup of Sino-Tibetan called "Sinitic" comprising Bai and Chinese.[4] The precise affiliation of Bai remains uncertain,[5] but the term "Sinitic" is usually used as a synonym for Chinese, especially when viewed as a language family.[6]

- ^ John DeFrancis proposed the neologism regionalect to serve as a translation for fāngyán when referring to mutually unintelligible divisions.[84] Victor Mair coined the term topolect as a translation for all uses of fāngyán.[85] The latter term appears in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.

- ^ Some words of literary origin with voiced initials shifted to category 6.[131]

- ^ a b The tone numbers of § Tones are used to facilitate comparison between dialects.

- ^ a b c The colloquial layers of southern Wu and coastal Min varieties use cognates of 儂 for 'person'.[136]

References

Citations

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 211–214.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1984), p. 3.

- ^ Wurm et al. (1987), Map A2.

- ^ Wang (2005), p. 107.

- ^ Wang (2005), p. 122.

- ^ Mair (1991), p. 3.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 183.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 183, 185.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 185.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 183–190.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 22.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 136.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 3–15.

- ^ Bradley (1992), pp. 309–312.

- ^ Bradley (1992), pp. 313–318.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 46–49.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 247.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 187.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 1.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 2.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 7.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 16–18.

- ^ a b c Norman (2003), p. 72.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 188.

- ^ Xiong & Zhang (2012), pp. 3, 125.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 36–41.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 41–53.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 181.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 53–55, 61, 215.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 90.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 199–200.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 46, 49–50.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 148.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 207–209.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), p. 49.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 233.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 232–233.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 224.

- ^ a b c Norman (1988), p. 217.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 215.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 98.

- ^ Wurm et al. (1987).

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 222–223.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 43–44, 48, 69, 75–76.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 235.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Xiong & Zhang (2012), pp. 161, 188, 189, 195.

- ^ Cao (2008a), p. 9.

- ^ Nakanishi (2010).

- ^ Coblin (2019), p. 438–443.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 290–291.

- ^ Norman (2003), pp. 73, 75.

- ^ Wang (2005).

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 182.

- ^ a b Norman (2003), pp. 73, 76.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Maps 4, 52, 66, 73.

- ^ Cao (2008b), Maps 5, 52, 79, 109, 134, 138.

- ^ Cao (2008c), Maps 3, 28, 38, 41, 76.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), pp. 182–183.

- ^ Chappell (2015b), pp. 45–51.

- ^ Norman (2003), p. 76.

- ^ Iwata (2010), pp. 102–108.

- ^ Iwata (1995), pp. 211–212.

- ^ Iwata (1995), pp. 215–216, 218.

- ^ Tang & van Heuven (2009), pp. 713–714.

- ^ Tang & van Heuven (2009), p. 712.

- ^ Tang & van Heuven (2009), pp. 715–717.

- ^ Tang & van Heuven (2009), pp. 718–722.

- ^ Tang & van Heuven (2009), pp. 721–722.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Liang (2014), p. 14.

- ^ Mair (2013).

- ^ Eberhard, Simons & Fennig (2024).

- ^ Chappell (2015a), p. 8.

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 3–6.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), p. 2.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), p. 63.

- ^ a b c DeFrancis (1984), p. 57.

- ^ Mair (1991), p. 7.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 138–139.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 212–213.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 101.

- ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 186–188.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 69, 90, 127.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 139, 236.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 66.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 127.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 211, 233.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 199–200, 207.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 91, 108–109, 152.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 235–236.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 193.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 182, 193, 200, 205.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 40.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 45.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 43.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 52.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 73.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 124.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 28, 141.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 150–151.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 141, 198.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 194.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 200–201.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 216–217.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 237.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 193, 201–202.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 193, 201.

- ^ Cao (2008a), Map 1.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 9.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 147, 202, 239.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 54.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 34–36.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 53.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), pp. 195–196, 272.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 108, 116–117.

- ^ Yan (2006), pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 202.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 225–226.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 198.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 218.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 146–147.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 202, 239.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 148–149, 195.

- ^ a b Beijing University (1989).

- ^ Cao (2008b), Map 39.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 17–19, 213–214, 219, 231–232.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), pp. 606–607.

- ^ a b Yue (2017), p. 114.

- ^ Cao (2008c), Map 76.

- ^ Yue (2017), p. 130.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), p. 606.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 1.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 2–4.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), pp. 607–608.

- ^ a b Yue (2017), p. 115.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 182, 214.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 196.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 208.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 205.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 203.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 234.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 227.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 220.

- ^ a b Yue (2017), p. 116.

- ^ Yue (2017), p. 117.

- ^ Chen (2015), p. 81.

- ^ Chen (2015), p. 106.

- ^ a b Yue (2017), p. 150.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), p. 623.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 227–232.

- ^ Yue (2017), p. 121.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 111.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 23.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 223.

- ^ Yue (2017), p. 131.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 125.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 31.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Yue (2017), pp. 153–154.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 173–178.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 173–174.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), p. 608.

- ^ Yue (2017), pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 49.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 42.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 44–47.

- ^ Yue (2017), pp. 136–137.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 196, 200, 204.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 196–197, 203–204.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 213.

- ^ Chappell & Li (2016), p. 607.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 92.

- ^ Li (2001), pp. 341–343.

- ^ Yue (2017), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), pp. 143, 146.

- ^ Yue (2017), pp. 147–148.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 159.

- ^ a b Yue (2017), p. 124.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1993), p. 69.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 57.

- ^ Hsieh (2007), pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Hsieh (2007), p. 15.

- ^ Hsieh (2007), pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Hsieh (2007), p. 17.

- ^ Hsieh (2007), pp. 20–21.

- ^ "The Goh Report". Archived from the original on 2 October 2013.

- ^ Manfred Whoa Man-Fat, "A Critical Evaluation of Singapore's Language Policy and its Implications for English Teaching", Karen's Linguistics Issues. Retrieved on 4 November 2010

- ^ Bokhorst-Heng, W.D. (1998). "Unpacking the Nation". In Allison D. et al. (Ed.), Text in Education and Society (pp. 202–204). Singapore: Singapore University Press.

- ^ Lee, Kuan Yew (2000). From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965–2000. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019776-6.

- ^ Lim, Siew Yeen; Yak, Jessie (4 July 2013). "Speak Mandarin Campaign". Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board, Singapore. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ (in Chinese) "讲华语运动30年 对象随大环境改变", Hua Sheng Bao, 17 March 2009.

- ^ Bokhorst-Heng, Wendy (1999). "Singapore's Speak Mandarin Campaign: Language ideological debates and the imagining of the nation". In Blommaert, Jan (ed.). Language Ideological Debates. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 235–265. ISBN 978-3-11-016350-6.

- ^ Wee, Lionel (2006). "The semiotics of language ideologies in Singapore". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 10 (3): 344–361. doi:10.1111/j.1360-6441.2006.00331.x.

Works cited

- Beijing University (1989), Hànyǔ fāngyīn zìhuì 汉语方音字汇 [Dictionary of Dialect Pronunciations of Chinese Characters] (PDF) (in Chinese) (2nd ed.), Beijing: Wenzi gaige chubanshe, ISBN 978-7-80029-000-8.

- Bradley, David (1992), "Chinese as a Pluricentric Language", in Clyne, Michael G. (ed.), Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 305–324, ISBN 978-3-11-012855-0.

- Cao, Zhiyun, ed. (2008a), Hànyǔ fāngyán dìtú jí 汉语方言地图集 [Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects] (in Chinese), vol. 1 (Phonetics), Beijing: Commercial Press, ISBN 978-7-100-05774-5.

- ———, ed. (2008b), Hànyǔ fāngyán dìtú jí 汉语方言地图集 [Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects] (in Chinese), vol. 2 (Lexicon), Beijing: Commercial Press, ISBN 978-7-100-05784-4.

- ———, ed. (2008c), Hànyǔ fāngyán dìtú jí 汉语方言地图集 [Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects] (in Chinese), vol. 3 (Grammar), Beijing: Commercial Press, ISBN 978-7-100-05785-1.

- Chappell, Hilary M. (2015a), "Introduction: Ways of tackling diversity in Sinitic languages", in Chappell, Hilary M. (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic Languages, Oxford University Press, pp. 3–12, ISBN 978-0-19-872379-0.

- ——— (2015b), "Linguistic areas in China for differential object marking, passive, and comparative constructions", in Chappell, Hilary M. (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic Languages, Oxford University Press, pp. 13–52, ISBN 978-0-19-872379-0.

- ———; Li, Lan (2016), "Mandarin and other Sinitic languages", in Chan, Sin-wai (ed.), The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language, Routledge, pp. 606–628, ISBN 978-0-415-53970-8.

- Chen, Ping (1999), Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.

- Chen, Yujie (2015), "The semantic differentiation of demonstratives in Sinitic languages", in Chappell, Hilary M. (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic Languages, Oxford University Press, pp. 81–109, ISBN 978-0-19-872379-0.

- Coblin, W. South (2019), Common Neo-Hakka: A Comparative Reconstruction, Language and linguistics Monograph Series, vol. 63, Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, ISBN 978-986-54-3228-7.

- DeFrancis, John (1984), The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2024), Ethnologue: Languages of the World (27th ed.), Dallas, TX: SIL International.

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Mei (2007), Exploring teachers' views about native language instruction and education in Taiwanese elementary schools (PhD thesis), University of Texas at Austin, hdl:2152/3598.

- Iwata, Ray (1995), "Linguistic geography of Chinese dialects: Project on Han dialects (PHD)", Cahiers de linguistique – Asie orientale, 24 (2): 195–227, doi:10.3406/clao.1995.1475.

- ——— (2010), "Chinese Geolinguistics: History, Current Trend and Theoretical Issues", Dialectologia, Special issue I: 97–121.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects", Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- Li, Ying-Che (2001), "Aspects of historical-comparative syntax: functions of prepositions in Taiwanese and Mandarin", in Chappell, Hilary M. (ed.), Sinitic grammar: synchronic and diachronic perspectives, Oxford University Press, pp. 340–368, ISBN 978-0-19-829977-6.

- Liang, Sihua (2014), Language Attitudes and Identities in Multilingual China: A Linguistic Ethnography, Springer, ISBN 978-3-319-12618-0.

- Mair, Victor H. (1991), "What Is a Chinese 'Dialect/Topolect'? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 29: 1–31.

- ——— (2013), "The Classification of Sinitic Languages: What Is 'Chinese'?" (PDF), in Cao, Guangshun; Djamouri, Redouane; Chappell, Hilary; Wiebusch, Thekla (eds.), Breaking Down the Barriers: Interdisciplinary Studies in Chinese Linguistics and Beyond, Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, pp. 735–754, ISBN 978-986-03-7678-4, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2018, retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Nakanishi, Hiroki (2010), "Lùn Shēhuà de guīshǔ" 论畬话的归属 [On the genetic affiliation of Shehua], Journal of Chinese Linguistics (in Chinese), 24: 247–267, JSTOR 23825447.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ——— (2003), "The Chinese dialects: phonology", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 72–83, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin George (1984), Middle Chinese: A Study in Historical Phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Tang, Chaoju; van Heuven, Vincent J. (2009), "Mutual intelligibility of Chinese dialects experimentally tested", Lingua, 119 (5): 709–732, doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2008.10.001, hdl:1887/14919.

- Wang, Feng (2005), "On the genetic position of the Bai language", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 34 (1): 101–127, doi:10.3406/clao.2005.1728.

- Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Li, Rong; Baumann, Theo; Lee, Mei W. (1987), Language Atlas of China, Longman, ISBN 978-962-359-085-3.

- Xiong, Zhenghui; Zhang, Zhenxing, eds. (2012), Zhōngguó yǔyán dìtú jí: Hànyǔ fāngyán juǎn 中国语言地图集:汉语方言卷 [Language Atlas of China: Chinese dialects] (in Chinese) (2nd ed.), Beijing: The Commercial Press, ISBN 978-7-10-007054-6.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006), Introduction to Chinese Dialectology, LINCOM Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Yue-Hashimoto, Anne (1993), Comparative Chinese Dialectal Grammar: Handbook for Investigators, Paris: École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l'Asie orientale, ISBN 978-2-910216-00-9.

- Yue, Anne O. (2017), "The Sinitic languages: grammar", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan Languages (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 114–163, ISBN 978-1-138-78332-4.

Further reading

- Ao, Benjamin (1991), "Comparative reconstruction of proto-Chinese revisited", Language Sciences, 13 (3/4): 335–379, doi:10.1016/0388-0001(91)90022-S.

- Baron, Stephen P. (1983), "Chain shifts in Chinese historical phonology: problems of motivation and functionality", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 12 (1): 43–63, doi:10.3406/clao.1983.1125.

- Ben Hamed, Mahé (2005), "Neighbour-nets portray the Chinese dialect continuum and the linguistic legacy of China's demic history", Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272 (1567): 1015–1022, doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3015, JSTOR 30047639, PMC 1599877, PMID 16024359.

- ———; Wang, Feng (2006), "Stuck in the forest: Trees, networks and Chinese dialects", Diachronica, 23 (1): 29–60, doi:10.1075/dia.23.1.04ham.

- Branner, David Prager (2000), Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology – the Classification of Miin and Hakka, Trends in Linguistics series, vol. 123, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-015831-1.

- Chappell, Hilary (2001), "Synchrony and diachrony of Sinitic languages: A brief history of Chinese dialects" (PDF), in Chappell, Hilary (ed.), Sinitic grammar: synchronic and diachronic perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–28, ISBN 978-0-19-829977-6.

- ———; Li, Ming; Peyraube, Alain (2007), "Chinese linguistics and typology: the state of the art", Linguistic Typology, 11 (1): 187–211, doi:10.1515/LINGTY.2007.014, S2CID 123103670.

- Escure, Geneviève (1997), Creole and Dialect Continua: standard acquisition processes in Belize and China (PRC), John Benjamins, ISBN 978-90-272-5240-1.

- Francis, Norbert (2016), "Language and dialect in China", Chinese Language and Discourse, 7 (1): 136–149, doi:10.1075/cld.7.1.05fra.

- Groves, Julie M. (2008), "Language or Dialect – or Topolect? A Comparison of the Attitudes of Hong Kongers and Mainland Chinese towards the Status of Cantonese" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 179: 1–103.

- Handel, Zev (2015), "The Classification of Chinese: Sinitic (The Chinese Language Family)", in Wang, William S. Y.; Sun, Chaofen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, Oxford University Press, pp. 34–44, ISBN 978-0-19-985633-6.

- Hannas, William C. (1997), Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaiʻi Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Norman, Jerry (2006), "Common Dialectal Chinese", in Branner, David Prager (ed.), The Chinese Rime Tables: Linguistic Philosophy and Historical-Comparative Phonology, Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, Series IV: Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, vol. 271, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 233–254, ISBN 978-90-272-4785-8.

- Sagart, Laurent (1998), "On distinguishing Hakka and non-Hakka dialects", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 26 (2): 281–302, JSTOR 23756757.

- Simmons, Richard VanNess (1999), Chinese Dialect Classification: A comparative approach to Harngjou, Old Jintarn, and Common Northern Wu, John Benjamins, ISBN 978-90-272-8433-4.

- ———, ed. (2022), Studies in Colloquial Chinese and Its History : Dialect and Text, Hong Kong University Press, ISBN 978-988-8754-09-0.

- Tam, Gina Anne (2020), Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781108776400, ISBN 978-1-108-77640-0.

- Hatano Tarō (波多野太郎) (1966), 中国方志所錄方言滙編 [Compilation of Chinese dialects in local chronicles] (in Japanese), Yokohama shiritsu daigaku kiyō, OCLC 50634504

- Chen Xiaojin (陈晓锦) Gan Yu'en (甘于恩) (2010), 东南亚华人社区汉语方言概要 [Summary of Local Chinese Dialects in Southeast Asian Overseas Communities] (in Chinese), Guangzhou: World Publishing, ISBN 978-7-510-08769-1.

External links

- Hànyǔ Fāngyīn Zìhuì 汉語方音字汇 [Dictionary of Chinese dialect pronunciations], Beijing University, 1962.

- DOC (Dialects of China or Dictionary on Computer) files at the Wayback Machine (archived 18 October 2005), compiled by William Wang and Chin-Chuan Cheng (archived from the originals at City University of Hong Kong)

- HTML version at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 June 2015) compiled by Dylan W.H. Sung

- Chinese Dialects: search interface to the DOC database, at StarLing

- Hànyǔ Fāngyīn Cíhuì 汉語方音词汇 [Chinese dialect vocabularies], Beijing University, 1964.

- CLDF dataset (Version v4.0). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3534942

- Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1981), Fāngyán diàochá zìbiǎo 方言调查字表 [Dialect survey character table] (PDF) (revised ed.), Beijing: Commercial Press.

- Chinese Dialect Geography – linguistic maps and commentaries from Iwata, Ray, ed. (2009), Interpretive maps of Chinese dialects, Tokyo: Hakuteisha Press.

- Technical Notes on the Chinese Language Dialects, by Dylan W.H. Sung (Phonology and Official Romanization Schemes)

![voiced obstruent initials[100]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/af/Map_of_distribution_of_voiced_initials_in_Chinese_dialects.svg/151px-Map_of_distribution_of_voiced_initials_in_Chinese_dialects.svg.png)

![retroflex initials[101]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Map_of_distribution_of_retroflex_initials_in_Chinese_dialects.svg/151px-Map_of_distribution_of_retroflex_initials_in_Chinese_dialects.svg.png)

![velar nasal initial (ŋ)[102]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/49/Map_of_distribution_of_the_velar_nasal_initial_in_Chinese_dialects.svg/151px-Map_of_distribution_of_the_velar_nasal_initial_in_Chinese_dialects.svg.png)

![retained m- where Beijing has w-[103]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Map_of_distribution_of_nasal_initial_in_%E9%97%AE_in_Chinese_dialects.svg/151px-Map_of_distribution_of_nasal_initial_in_%E9%97%AE_in_Chinese_dialects.svg.png)

![retained n- where Beijing has r-[104]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Map_of_distribution_of_nasal_initial_in_%E7%86%B1_in_Chinese_dialects.svg/151px-Map_of_distribution_of_nasal_initial_in_%E7%86%B1_in_Chinese_dialects.svg.png)