Coltan: Difference between revisions

m →Anthropological Perspectives: Try not to have 2 links beside one another, as less readable. Sony doesn't need linking anyway. |

174.91.155.15 (talk) citation change |

||

| Line 423: | Line 423: | ||

'''Resource Curse''' |

'''Resource Curse''' |

||

Countries rich in resources such as Congo have been affected by something called the “resource curse”.<ref> |

Countries rich in resources such as Congo have been affected by something called the “resource curse”.<ref>{{cite book|last=Humphreys et al|title=Escaping the Resource Curse|year=2007|publisher=Columbia University Press|location=New York|pages=1-2, 10-11}}</ref> The “resource curse” is used to describe the situation when countries rich in resources “often perform worse in terms of economic development…than countries with fewer resources”.<ref>https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse</ref> This phenomena does not allow for the Congolese to have a balanced and sustained development. There is little growth and there are “strong associations between resource wealth and the likelihood of weak democratic development, corruption, and civil war.”<ref>https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse</ref> Such high levels of corruption lead to great political instability and issues because “those who control these assets [mainly political leaders, and more specifically the government in Congo] can use that wealth to maintain themselves in power, either through legal means, or coercive ones (e.g. funding militias)”.<ref>https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse</ref> The beginning of coltan as an important mineral, crucial to technological products “occurred as warlords and armies in the eastern Congo converted artisanal mining operations…into slave labour regimes to earn hard currency to finance their militias”.<ref>http://mason.gmu.edu/~jmantz/Improvisational%20Economies.pdf</ref> Coltan has become “…a kind of blood diamond of the digital age”<ref>http://mason.gmu.edu/~jmantz/Improvisational%20Economies.pdf</ref> |

||

'''Digital Age''' |

'''Digital Age''' |

||

Revision as of 14:00, 4 March 2013

Coltan (short for columbite–tantalite and known industrially as tantalite) is a dull black metallic ore from which the elements niobium (formerly "columbium") and tantalum are extracted. The niobium-dominant mineral in coltan is columbite, and the tantalum-dominant mineral is tantalite.[1]

Tantalum from coltan is used to manufacture tantalum capacitors, used in electronic products. Coltan mining has been cited[2][3] as helping to finance serious conflict, for example the Ituri conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[4][5][6]

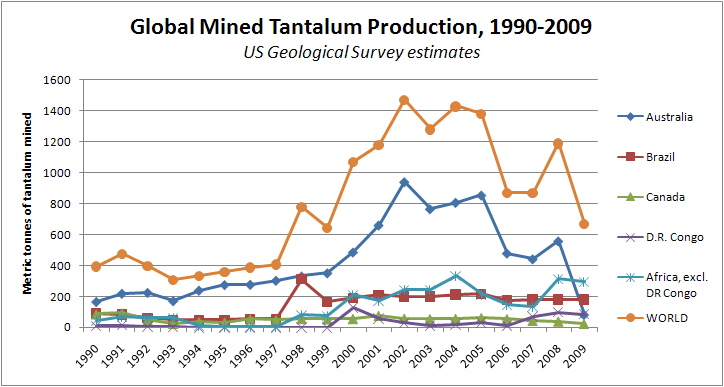

Production and supply

Approximately 71% of global tantalum supply in 2008 was met by newly mined product, 20% from recycling, and the remainder from tin slag and inventory.[7]

Tantalum minerals are mined in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo, China, Ethiopia, and Mozambique.[8] Tantalum is also produced in Thailand and Malaysia as a by-product of tin mining and smelting.

Potential future mines, in descending order of magnitude, are being explored in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Uganda, Greenland, China, Mozambique, Canada, Australia, the United States, Finland, Afghanistan,[9] and Brazil.[10] A significant reserve of coltan was discovered in 2009 in western Venezuela.[11] In 2009 the Colombian government announced coltan reserves had been found in Colombia's eastern provinces.[12]

| metric tons of tantalum mined | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Australia | 165 | 218 | 224 | 170 | 238 | 274 | 276 | 302 | 330 | 350 | 485 | 660 | 940 | 765 | 807 | 854 | 478 | 441 | 557 | 81 |

| Brazil | 90 | 84 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 55 | 310 | 165 | 190 | 210 | 200 | 200 | 213 | 216 | 176 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| Canada | 86 | 93 | 48 | 25 | 36 | 33 | 55 | 49 | 57 | 54 | 57 | 77 | 58 | 55 | 57 | 63 | 56 | 45 | 40 | 25 |

| D.R. Congo | 10 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | -- | -- | NA | NA | 130 | 60 | 30 | 15 | 20 | 33 | 14 | 71 | 100 | 87 |

| Africa, excl. DR Congo |

45 | 66 | 59 | 59 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 82 | 76 | 208 | 173 | 242 | 245 | 333 | 214 | 146 | 135 | 313 | 297 |

| WORLD | 396 | 477 | 399 | 310 | 333 | 361 | 389 | 409 | 779 | 645 | 1070 | 1180 | 1470 | 1280 | 1430 | 1380 | 870 | 872 | 1190 | 670 |

| 1990-1993: U.S. Geological Survey, "1994 Minerals Yearbook" (MYB), "COLUMBIUM (NIOBIUM) AND TANTALUM" By Larry D. Cunningham, Table 10; 1994-1997: MYB 1998, Table 10; 1998-2001: MYB 2002, p. 21.13; 2002-2003: MYB 2004, p. 20.13; 2004: MYB 2008, p. 52.12; 2005-2009: MYB 2009, p. 52.13. USGS did not report data for other countries (China, Kazakhstan, Russia, etc.) owing to data uncertainties. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| NA Not available. -- Zero. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| % of global mined tantalum production | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Australia | 41.7% | 45.7% | 56.1% | 54.8% | 71.5% | 75.9% | 71.0% | 73.8% | 42.4% | 54.3% | 45.3% | 55.9% | 63.9% | 59.8% | 56.4% | 61.9% | 54.9% | 50.6% | 46.8% | 12.1% |

| Brazil | 22.7% | 17.6% | 15.0% | 16.1% | 15.0% | 13.9% | 14.1% | 13.4% | 39.8% | 25.6% | 17.8% | 17.8% | 13.6% | 15.6% | 14.9% | 15.7% | 20.2% | 20.6% | 15.1% | 26.9% |

| Canada | 21.7% | 19.5% | 12.0% | 8.1% | 10.8% | 9.1% | 14.1% | 12.0% | 7.3% | 8.4% | 5.3% | 6.5% | 3.9% | 4.3% | 4.0% | 4.6% | 6.4% | 5.2% | 3.4% | 3.7% |

| D.R. Congo | 2.5% | 3.4% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.1% | 5.1% | 2.0% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 2.4% | 1.6% | 8.1% | 8.4% | 13.0% |

| Africa. excl. DR Congo |

11.4% | 13.8% | 14.8% | 19.0% | 2.4% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 10.5% | 11.8% | 19.4% | 14.7% | 16.5% | 19.1% | 23.3% | 15.5% | 16.8% | 15.5% | 26.3% | 44.3% |

| WORLD | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Use and demand

Coltan is used primarily for the production of tantalum capacitors, used in many electronic devices. Many sources mention coltan's importance in the production of cell phones, but this is an over-simplification, as tantalum capacitors are used in almost every kind of electronic device.

It is also used in high temperature alloys for air and land based turbines.[14] The upsurge in electronic products over the past decade resulted in a peak in late 2000, lasting a few months. In 2005 the price was still down at early 2000 levels.[15][16]

The United States Geological Survey estimates that tantalum production capacity could meet global demand, which is growing at four percent annually, at least until the year 2013.[7]

Anthropological Perspectives

Resource Curse Countries rich in resources such as Congo have been affected by something called the “resource curse”.[17] The “resource curse” is used to describe the situation when countries rich in resources “often perform worse in terms of economic development…than countries with fewer resources”.[18] This phenomena does not allow for the Congolese to have a balanced and sustained development. There is little growth and there are “strong associations between resource wealth and the likelihood of weak democratic development, corruption, and civil war.”[19] Such high levels of corruption lead to great political instability and issues because “those who control these assets [mainly political leaders, and more specifically the government in Congo] can use that wealth to maintain themselves in power, either through legal means, or coercive ones (e.g. funding militias)”.[20] The beginning of coltan as an important mineral, crucial to technological products “occurred as warlords and armies in the eastern Congo converted artisanal mining operations…into slave labour regimes to earn hard currency to finance their militias”.[21] Coltan has become “…a kind of blood diamond of the digital age”[22]

Digital Age Coltan is made into a component for many digital products such as cell phones. The digital age has caused issues regarding power relations and violence between individuals from the Congo and the rest of the world. An example of uneven power relations was in late 2000, when there was a great demand for the Sony PlayStation 2. This demand caused the price of coltan to increase very quickly and after demand for the gaming system fell, so did the price of coltan.[23] The price hike of coltan had made the violence in eastern Congo a lot worse, as the violence was being directed at everyday "social production".[24] Since there is a growing need for new technologies, the demand for coltan is growing substantially.

Mining For individuals living within the Congo, mining is the easiest source of income available, as the work is consistent and regular, even if just for $1/day.[25] However, coltan is laborious to mine, as it takes around “three day’s march into the forests to scratch out the ore with hand tools and pan it … about 90 per cent of young men are doing this now…”.[26] Congolese individuals can try to work in places like farms, but they will have to wait for their crops to grow and then they have a high chance of their harvest being taken by militias and the Congolese army.[27] Once their food is taken away or they no longer have the capacity to grow food, they need to resort to mining in order to sustain themselves and provide for families.

Some other reasons for the Congolese to work in mines rather than farming include:[28]

- They need money quickly, so rather than waiting for months for their plants to grow enough to harvest, they are better off mining.

- There are no roads for people to travel on, making it extremely difficult for people to get their produce to rural markets.

- Farming is more insecure because there are no regulating bodies to protect them from armed people that may try to steal their food.

Artisanal Mining A lot of the miners in the Congo are mining artisanally, that is, they are lawless and entrepreneurial. This is because organized mines are usually run by corrupt groups like militias. There are little tools available for the Congolese to efficiently mine for coltan, with no safety procedures or past experience working in mines.[29] There is no government aid or intervention in many unethical and abusive circumstances. Coltan mining is viewed by miners as a way of providing for themselves in an area where war and internal conflict are widespread and the government has no concern for citizen’s welfare.[30]

Ethics of Coltan mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo

See also: Coltan mining and ethics

Conflicts, including the Rwandan occupation in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) made it difficult for the DRC to exploit its coltan reserves. Mining of the mineral is mainly artisanal and small-scale.[31] A 2003 UN Security Council report[32] charged that a great deal of the ore is mined illegally and smuggled over the country's eastern borders by militias from neighbouring Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda.[33]

All three countries named by the United Nations as smugglers of coltan have denied being involved. Austrian journalist Klaus Werner has documented links between multi-national companies like Bayer and the illegal coltan traffic.[34] A United Nations committee investigating the plunder of gems and minerals in the Congo listed in its final report[32] approximately 125 companies and individuals involved in business activities breaching international norms. Companies accused of irresponsible corporate behavior are for example the Cabot Corporation,[35] Eagle Wings Resources International[36] Forrest Group[37] and OM Group.[38]

Coltan smuggling likely provides income for the military occupation of Congo[citation needed], as well as prolonged civil conflict. To many[who?], this raises ethical questions akin to those of blood diamonds. Owing to the difficulty of distinguishing legitimate from illegitimate mining operations, several processors such as Cabot Corp (USA) have decided to forgo central African coltan altogether, relying on other sources.[citation needed]

Much coltan from the DRC is being exported to China for processing into electronic-grade tantalum powder and wires.[39]

Estimates of the Congo's fraction of the world's coltan reserves range from 64% and up.[40] Tantalum, the primary mineral extracted from Coltan is also mined from other sources, and Congolese coltan represented around 10% of world production in recent years.[41][42]

Environmental concerns

Because of uncontrolled mining in the DRC, the land is being eroded and is polluting lakes and rivers, affecting the ecology of the region[citation needed].

The Eastern Mountain Gorilla's population has diminished as well. Miners are far from food sources and have been hunting gorillas.[43] The gorilla population has been seriously reduced and is now critically endangered. In Central and West Africa an estimated 3–5 million tons of so-called "bush meat" is obtained by killing wild animals (including gorillas) each year.[44]

Price increases and changing demands

There has been a significant drop in the production and sale of coltan and niobium from African mines since the dramatic price spike in 2000, based on dot com speculation and multiple ordering. This is confirmed in part by figures from the United States Geological Survey.[45][46]

The Tantalum-Niobium International Study Centre in Belgium, a country with traditionally close links to the Congo, has encouraged international buyers to avoid Congolese coltan on ethical grounds:

The central African countries of Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda and their neighbours used to be the source of significant tonnages. But civil war, plundering of national parks and exporting of minerals, diamonds and other natural resources to provide funding of militias has caused the Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center to call on its members to take care in obtaining their raw materials from lawful sources. Harm, or the threat of harm, to local people, wildlife or the environment is unacceptable.[47]

For economic rather than ethical reasons, a shift is also being seen from traditional sources such as Australia, towards new suppliers such as Egypt.[48] This may have been brought about by the bankruptcy of the world's biggest supplier, Australia's Sons of Gwalia. The operations previously owned by Gwalia in Wodgina and Greenbushes continue to operate in some capacity.

References

- ^ Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center, Coltan, retrieved 2008-01-27

- ^ Congo: war-torn heart of Africa, December 1, 2008, retrieved 2012-10-18

- ^ Breaking the Silence- Congo Week, December 15, 2009, retrieved 2011-10-11

- ^ http://www.vice.com/vice-news/the-vice-guide-to-congo-1

- ^ Söderberg, Mattias (2006-09-22), Is there blood on your mobile phone?, retrieved 2009-05-16

- ^ "IRC Study Shows Congo's Neglected Crisis Leaves 5.4 Million Dead; Peace Deal in N. Kivu, Increased Aid Critical to Reducing Death Toll". 22 January 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ a b Papp, John F. (January 2011), "Niobium (Columbium) and Tantalum", U.S. Geological Survey, 2009 Minerals Yearbook, pp. 52.1 - 52.14 (PDF), retrieved 2011-01-17

- ^ US Geological Survey (2006), Minerals Yearbook Nb & Ta, United States Geological Survey, retrieved 2008-06-03

- ^ http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=12486

- ^ Mining Journal (2007-November), Tantalum supplement (PDF), retrieved 2008-06-03

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.venezuelanalysis.com/news/4869, October 16th, 2009

- ^ http://www.semana.com/noticias-nacion/guerra-coltan/131652.aspx, November 21st, 2009

- ^ 1990-1993: U.S. Geological Survey, 1994 Minerals Yearbook (MYB), "COLUMBIUM (NIOBIUM) AND TANTALUM" By Larry D. Cunningham, Table 10; 1994-1997: MYB 1998 Table 10; 1998-2001: MYB 2002 p. 21.13; 2002-2003: MYB 2004 p. 20.13; 2004: MYB 2008 p. 52.12; 2005-2009: MYB 2009 p. 52.13. USGS did not report data for other countries (China, Kazakhstan, Russia, etc.) owing to data uncertainties. .

- ^ Applications for Tantalum, retrieved 2008-06-03

- ^ The Economics of Tantalum, retrieved 2008-06-03

- ^ Coltan Facts, 2009, retrieved 2009-12-17

- ^ Humphreys; et al. (2007). Escaping the Resource Curse. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 1–2, 10–11.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse

- ^ https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse

- ^ https://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-14196-3/escaping-the-resource-curse

- ^ http://mason.gmu.edu/~jmantz/Improvisational%20Economies.pdf

- ^ http://mason.gmu.edu/~jmantz/Improvisational%20Economies.pdf

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01289.x/abstract

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01289.x/abstract

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01289.x/abstract

- ^ http://www.roape.org/093/10.html

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01289.x/abstract

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01289.x/abstract

- ^ http://mason.gmu.edu/~jmantz/Improvisational%20Economies.pdf

- ^ http://www.roape.org/093/10.html

- ^ Dorner, Ulrike (2012-03-01). "Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM)" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

S/2003/1027, United Nations, 2003-10-26, retrieved 2008-04-19

{{citation}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Security Council Condemns Illegal Exploitation of Democratic Republic of Congo's Natural Resources" (Press release). UN. 3 May 2001. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Werner, Klaus, 2003,The New Black Book of Brand Companies (in German Das neue Schwarzbuch Markenfirmen), ISBN 3-216-30715-8

- ^ Friend of the Earth-United States (2004-08-04), FOE complaint to Department of State concerning U.S. companies, retrieved 2009-05-15

- ^ Friend of the Earth-United States (2004-08-04), Groups File Complaint With State Department Against Three American Companies Named in UN Report, retrieved 2009-05-15

- ^ BBC (2006-04-17), Scramble for DR Congo's mineral wealth, BBC News Online, retrieved 2008-04-19

- ^ Friends of the Congo, Coltan: What You Should Know, retrieved 2008-04-19

- ^ Tiffany Ma, "China and Congo's Coltan Connection," Project 2049 Futuregram (09-003), June 22, 2009, at http://project2049.net/documents/china_and_congos_coltan_connection.pdf

- ^ "The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Major Challenges Impede Efforts to Achieve U.S. Policy Objectives; Systematic Assessment of Progress Is Needed" GAO-08-562T, March 6, 2008 http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08562t.pdf -- on request for their source the GAO gave the Golbal Witness report "Under-Mining Peace: Tin - the Explosive Trade in Cassiterite in Eastern DRC" June 30, 2005 http://www.globalwitness.org/media_library_detail.php/138/en/

- ^ http://tanb.org/coltan

- ^ http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/niobium/myb1-2008-niobi.pdf

- ^ Taylor and Goldsmith, Andrea and Michele (December 2002), Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, ISBN 978-0-521-79281-3, retrieved 2010-11-19

- ^ Olive, Brooke (August 21, 2007), Mountain Gorillas, Bushmeat or Blackmail?, retrieved 2009-12-17

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2002, Tantalum p. 166-7

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2005, Tantalum p. 166-7

- ^ Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center, Tantalum, retrieved 2008-01-27

- ^ Gippsland Limited, Abu Dabbab Tantalum, retrieved 2011-04-02

External links

- UN Coltan Explainer

- High-Tech Genocide in Congo, by Keith Harmon Snow.

- Issia, Cote d'Ivoire, Coltan Deposits

- Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting Congo's Bloody Coltan (Video)

- ABC Late Night Live interview with Michael Nest Coltan (Audio)

- Blood Coltan (Video)

- Coltan, Gorillas and cellphones

- Congo's Tragedy: The War The World Forgot

- Cellphones fuel Congo conflict

- Human cost of mining in DR Congo

- Our Cell Phones, Their War

- Forced Child-Labor PlayStation Miners

- Fairphone - Fairtrade Phone Project

- Coltan: a new blood mineral

- Conflict Minerals Company Rankings, technology company classification surveying their compromise to avoid the use of "conflict minerals". Report from Raise Hope for Congo information campaign, of Enough Project.