Bucklin voting: Difference between revisions

m →Satisfied and failed criteria: link name |

→Voting process: remove Majority Choice Approval since its article was deleted |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

First choice votes are first counted. If one candidate has a [[majority]], that candidate wins. Otherwise the second choices are added to the first choices. Again, if a candidate with a majority vote is found, the winner is the candidate with the most votes accumulated. Lower rankings are added as needed. |

First choice votes are first counted. If one candidate has a [[majority]], that candidate wins. Otherwise the second choices are added to the first choices. Again, if a candidate with a majority vote is found, the winner is the candidate with the most votes accumulated. Lower rankings are added as needed. |

||

A [[majority]] is determined based on the number of valid ballots. Since, after the first round, there may be more votes cast than voters, it is possible for more than one candidate to have majority support. This makes Bucklin a variation of [[approval voting]] |

A [[majority]] is determined based on the number of valid ballots. Since, after the first round, there may be more votes cast than voters, it is possible for more than one candidate to have majority support. This makes Bucklin a variation of [[approval voting]]. |

||

==Bucklin applied to multiwinner elections== |

==Bucklin applied to multiwinner elections== |

||

Revision as of 00:06, 12 June 2010

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

Bucklin voting is the name of a voting system that can be used for single-member and multi-member districts. It is named after its original promoter, James W. Bucklin of Grand Junction, Colorado, and also known as the Grand Junction system.

Voting process

Voters are allowed rank preference ballots (first, second, third, etc.). In some variants, equal ranking is allowed at some or all ranks. Some variants have a predetermined number of ranks available (usually 2 or 3), while others have unlimited ranks.

First choice votes are first counted. If one candidate has a majority, that candidate wins. Otherwise the second choices are added to the first choices. Again, if a candidate with a majority vote is found, the winner is the candidate with the most votes accumulated. Lower rankings are added as needed.

A majority is determined based on the number of valid ballots. Since, after the first round, there may be more votes cast than voters, it is possible for more than one candidate to have majority support. This makes Bucklin a variation of approval voting.

Bucklin applied to multiwinner elections

Bucklin was used for multiwinner elections. [citation needed] For multi-member districts, voters marked as many first choices as there are seats to be filled. Voters marked the same number of second and further choices. In some localities, the voter was required to mark a full set of first choices for his or her ballot to be valid. However, allowing voters to cast three simultaneous votes for three seats could allow an organized 51% to win all three seats in the first round.

History and Usage

The method was proposed by Condorcet in 1793.[1] It was used in many political elections in the United States in the early 20th century, as were other experimental election methods during the progressive era. In all states it was eventually repealed or, in two states, it was found to violate the state constitution. In Minnesota, it was ruled unconstitutional, in a decision that disallowed votes for multiple candidates, in opposition to some voters' single expressed preference,[2] and in Oklahoma, the particular application required voters to rank more than one candidate, when there were more than two, or the vote would not be counted, and the preferential primary was, for that reason, found unconstitutional. The canvassing method itself was not rejected in Oklahoma.[3]

Satisfied and failed criteria

Bucklin voting satisfies the majority criterion, the mutual majority criterion and the monotonicity criterion.[4]

Bucklin voting without equal rankings allowed fails the Condorcet criterion, independence of clones criterion,[5] later-no-harm, participation, consistency, reversal symmetry, the Condorcet loser criterion and the independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion

There are no reliable sources for the criteria failed by Bucklin if equal rankings are allowed. However, a degenerate form of equal-rankings Bucklin with only one approved rank allowed is equivalent to Approval voting, and so would pass/fail the same criteria.

Example application

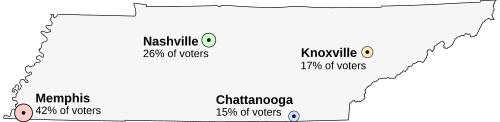

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| City | Round 1 | Round 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42 | 42 |

| Nashville | 26 | 68 |

| Chattanooga | 15 | 58 |

| Knoxville | 17 | 32 |

The first round has no majority winner. Therefore the second rank votes are added. This moves Nashville and Chattanooga above 50%, so a winner can be determined. Since Nashville is supported by a higher majority (68% versus 58%), Nashville is the winner.

Voter strategy

Voters supporting a strong candidate have an incentive to bullet vote (offer only one first-rank vote), in hopes that other voters will add enough votes to help their candidate win. This strategy is most secure if the supported candidate appears likely to gain many second-rank votes.

In the above example, Memphis voters have the most first-place votes and might not offer a second preference in hopes of winning, but the strategy fails because they are not a second-place choice of competitors.

Chattanooga voters could cause their candidate to win by bullet voting. However, if they did, they might force Nashville voters to retaliate in kind, which would leave Nashville as the winner. Knoxville voters, who would know that a bullet strategy had no hope for them, would then be enough, though barely, to protect Nashville from bullet voting by Memphis.

See also

Notes

- ^ Principles and problems of government, Haines and Hanes, 1921

- ^ Brown v. Smallwood, 130 Minn. 492, 153 N. W. 953

- ^ Dove v. Oglesby, 114 Okla. 144, 244 p. 798

- ^ Collective decisions and voting: the potential for public choice, Nicolaus Tideman, 2006, p. 204

- ^ Tideman, 2006, ibid