Approval voting: Difference between revisions

24.186.166.83 (talk) No edit summary |

m regarding multiwinner proportionality |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Approval voting''' is a [[voting system]] used for [[election]]s, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as the voter chooses. It is typically used for single-winner elections without a percentage threshold, but can be extended to multiple winners and elections with a percentage threshold. ( |

'''Approval voting''' is a [[voting system]] used for [[election]]s, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as the voter chooses. It is typically used for single-winner elections without a percentage threshold, but can be extended to multiple winners and elections with a percentage threshold. (However, multi-winner Approval voting does not return [[proportional representation|proportional]] results.) Approval voting is a limited form of [[range voting]], where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not. |

||

extension is not a good idea since it can lead to severe proportionality failures, e.g. |

|||

100% Whig winners with only 51% Whig voters.) |

|||

Approval voting is a limited form of [[range voting]], where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not. |

|||

It was advocated in 1968 and 1977 by [[Guy Ottewell]]. The term "Approval voting" was first coined by [[Robert J. Weber]] in 1976, but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist [[Steven Brams]] and mathematician [[Peter Fishburn]]. Historically, something resembling |

It was advocated in 1968 and 1977 by [[Guy Ottewell]]. The term "Approval voting" was first coined by [[Robert J. Weber]] in 1976, but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist [[Steven Brams]] and mathematician [[Peter Fishburn]]. Historically, something resembling |

||

Revision as of 20:30, 8 September 2005

Approval voting is a voting system used for elections, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as the voter chooses. It is typically used for single-winner elections without a percentage threshold, but can be extended to multiple winners and elections with a percentage threshold. (However, multi-winner Approval voting does not return proportional results.) Approval voting is a limited form of range voting, where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not.

It was advocated in 1968 and 1977 by Guy Ottewell. The term "Approval voting" was first coined by Robert J. Weber in 1976, but was fully devised in 1977 and published in 1978 by political scientist Steven Brams and mathematician Peter Fishburn. Historically, something resembling Approval voting for candidates was used in the Republic of Venice during the 13th century and for elections in 19th century England.

Procedures

Each voter may vote for as many options as they wish, at most once per option. This is equivalent to saying that each voter may "approve" or "disapprove" each option by voting or not voting for it, and it's also equivalent to voting +1 or 0 in a range voting system.

The votes for each option are tallied. The option with the most votes wins.

Simple example

There are three candidates (A, B and C) for an election, and there are 10 persons voting. The table represents the results of the vote

A B C vote 1 1 0 0 vote 2 0 1 0 vote 3 0 0 1 vote 4 1 0 1 vote 5 1 1 1 vote 6 1 0 0 vote 7 0 0 1 vote 8 0 0 0 vote 9 1 0 0 vote 10 0 1 0 sum 5 3 4

Candidate A has the highest score, and wins.

Example

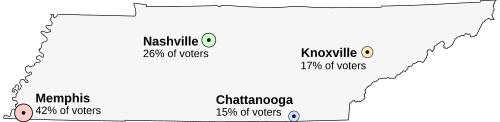

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Supposing that voters voted for their two favorite candidates, the results would be as follows (a more sophisticated approach to voting is discussed below):

- Memphis: 42 total votes

- Nashville: 68 total votes (wins)

- Chattanooga: 58 total votes

- Knoxville: 32 total votes

Potential for tactical voting

Approval voting passes a form of the monotonicity criterion, in that voting for a candidate never lowers that candidate's chance of winning. Indeed, there is never a reason for a voter to tactically vote for a candidate X without voting for all candidates he or she prefers to candidate X.

However, as approval voting does not offer a single method of expressing sincere preferences, but rather a plethora of them, voters are encouraged to analyze their fellow voters' preferences and use that information to decide which candidates to vote for. This feature of approval voting makes it difficult for theoreticians to predict how approval will play out in practice.

One good tactic is to vote for every candidate the voter prefers to the leading candidate, and to also vote for the leading candidate if that candidate is preferred to the current second-place candidate. When all voters use this tactic, there is a good chance that the Condorcet winner will be elected. It should be noted that approval voting does not satisfy the Condorcet criterion. It is even possible that a Condorcet loser can be elected.

In the above election, if Chattanooga is perceived as the strongest challenger to Nashville, voters from Nashville will only vote for Nashville, because it is the leading candidate and they prefer no alternative to it. Voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville will withdraw their support from Nashville, the leading candidate, because they do not support it over Chattanooga. The new results would be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 68

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

If, however, Memphis were perceived as the strongest challenger, voters from Memphis would withdraw their votes from Nashville, whereas voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville would support Nashville over Memphis. The results would then be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 58

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

The mathematics of approval voting lend it to some manipulation and tactical voting. As each vote counts as one vote and the winner is the one with the highest total, each vote equally helps the candidate/issue (city in this example) selected win. Because of this, voters are more likely to only vote for their favorite. Because AV has not been used much for real elections, this phenomenon is not well documented.

Effect on elections

The effect of this system as an electoral reform measure is disputed. Instant-runoff voting advocates like the Center for Voting and Democracy argue that Approval Voting would lead to the election of "lowest common denominator" candidates disliked by few, and liked by few. A study by Approval advocates Steven Brams and Dudley R. Herschbach published in Science in 2000 argued that approval voting was "fairer" than preference voting on a number of criteria. They claimed that a close analysis shows that the hesitation to support a lesser evil candidate to the same degree as one supports one's first choice actually outweighs the extra votes that such second choices get. It is known that approval voting would not have chosen the same two winners as plurality voting (Chirac and Le Pen) in France's presidential election of 2002 (first round) - it instead would have chosen Chirac and Jospin. This seems a more reasonable result since Le Pen was a radical who lost to Chirac by an enormous margin in the second round.

Other issues and comparisons

Advocates of approval voting often note that a single simple ballot can serve for single, multiple, or negative choices. It requires the voter to think carefully about who or what they really accept, rather than trusting a system of tallying or compromising by formal ranking or counting. Compromises happen but they are explicit, and chosen by the voter, not by the ballot counting. Some features of approval voting include:

- Unlike Condorcet method, instant-runoff voting, and other methods that require ranking candidates, approval voting does not require significant changes in ballot design, voting procedures or equipment, and it is easier for voters to use and understand. This reduces problems with mismarked ballots, disputed results and recounts.

- It provides less incentive for negative campaigning than many other systems, though the same incentive as instant runoff voting, condorcet method, and Borda count.

- It allows voters to express tolerances but not preferences. Some political scientists consider this a major advantage, especially where acceptable choices are more important than popular choices.

- Each voter may vote as many times as they wish, at most once per candidate. This is equivalent to saying that each voter may approve or disapprove each candidate by voting or not voting for them, and it's also equivalent to voting +1 or 0 in a range voting system.

- It is easily reversed as disapproval voting where a choice is disavowed, as is already required in other measures in politics (e.g. representative recall).

- In contentious elections with a super-majority of voters who prefer their favorite candidate vastly over all others, approval voting tends to revert to plurality voting. Some voters will support only their single favored candidate when they perceive the other candidates to be poor compromises.

- Approval voting fails the majority criterion, so a majority alone cannot determine a winner, but satisfies the weak defensive strategy criterion, so a majority can determine who loses.

Multiple winners

Approval voting can be extended to multiple winner elections, either as block approval voting, a simple variant on block voting where each voter can select an unlimited number of candidates and the candidates with the most approval votes win, or as proportional approval voting which seeks to maximise the overall satisfaction with the final result using approval voting. That first system has been called minisum to distinguish it from minimax, a system which uses approval ballots and aims to elect the slate of candidates that differs from the least-satisfied voter's ballot as little as possible.

Expressing the vote result as a percentage

Among several reasons why it can be desirable to express the vote result as a percentage, one that often occurs is the type of election where a candidate needs to have 50% of the votes in the first round.

In order to be able to express the result of an approval voting as a percentage, as well "blank votes" as "agree to all" votes have to be counted, but also they are counted differently (as opposed to non-range vote systems, where that distinction needs not to be made).

Making some variantions of the "simple example" above will show the difference. The percentages can be expressed as follows: A (winner): 50%; B: 30%; C: 40% (note that the sum of the percentages is not necessarily 100%, as in simpler types of voting systems). We follow the winner's percentage, introducing small differences, altering not more than (the interpretation of) a single voter's choice. The example has one "blank vote" (vote 8) and one "agree to all" vote (vote 5).

If discarding the blank vote:

A B C vote 1 1 0 0 vote 2 0 1 0 vote 3 0 0 1 vote 4 1 0 1 vote 5 1 1 1 vote 6 1 0 0 vote 7 0 0 1 vote 8 1 0 0 vote 9 0 1 0 sum 5 3 4

The "sum" of each vote remains the same, but the percentage of the winner goes up to over 55%

Similarly, if an 11th person who hadn't voted because he/she didn't like any of the candidates, now joins in:

A B C vote 1 1 0 0 vote 2 0 1 0 vote 3 0 0 1 vote 4 1 0 1 vote 5 1 1 1 vote 6 1 0 0 vote 7 0 0 1 vote 8 0 0 0 vote 9 1 0 0 vote 10 0 1 0 vote 11 0 0 0 sum 5 3 4

Again, the "sum" for each candidate remains the same, but this time the percentage of the "winner" lowers to about 45%.

If, in the original example vote 8 were counted "as if" it had been an "agree to all" vote:

A B C vote 1 1 0 0 vote 2 0 1 0 vote 3 0 0 1 vote 4 1 0 1 vote 5 1 1 1 vote 6 1 0 0 vote 7 0 0 1 vote 8 1 1 1 vote 9 1 0 0 vote 10 0 1 0 sum 6 4 5

Now also the vote counts go up by a unit, pushing the winner's result to 60%.

Similarily if counted "as if" the "agree to all" vote of No. 5 had been a blank vote:

A B C vote 1 1 0 0 vote 2 0 1 0 vote 3 0 0 1 vote 4 1 0 1 vote 5 0 0 0 vote 6 1 0 0 vote 7 0 0 1 vote 8 0 0 0 vote 9 1 0 0 vote 10 0 1 0 sum 4 2 3

the score of the winner lowers to 4 units, or 40%.

In traditional voting systems blank votes will either not affect the percentage of the winner, or heighten it. In such systems "Agree to all" votes are either discarded as illegitimate or added to the blank votes, and so also can not lower the winner's result. All this depends on how votes are counted in these systems, but there's no way for a voter to lower the winner's percentage. In approval voting the voter has at least a choice:

- "Agree to all" votes heighten the winner's percentage;

- "Blank" votes lower the winner's percentage.

And as equally important conclusion to these examples: if percentages are calculated for whatever reason, the advantages of the approval voting system, compared to traditional voting systems, are not fully exploited unless blank votes are possible and counted separately from "agree to all" votes!

Relation to effectiveness of choices

Operations research has shown that the effectiveness of a policy and thereby a leader who sets several policies will be sigmoidally related to the level of approval associated with that policy or leader. There is an acceptance level below which effectiveness is very low and above which it is very high. More than one candidate may be in the effective region, or all candidates may be in the ineffective region. Approval voting attempts to ensure that the most-approved candidate is selected, maximizing the chance that the resulting policies will be effective.

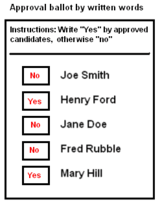

Ballot types

Approval ballots can be of at least four semi-distinct forms. The simplest form is a blank ballot where the names of supported candidates is written in by hand. A more structured ballot will list all the candidates and allow a mark or word to be made by each supported candidate. A more explicit structured ballot can list the candidates and give two choices by each. (Candidate list ballots can include spaces for write-in candidates as well.)

|

|

|

|

All four ballots are interchangeable. The more structured ballots may aid voters in offering clear votes so they explicitly know all their choices. The Yes/No format can help to detect an "undervote" when a candidate is left unmarked, and allow the voter a second chance to confirm the ballot markings are correct.

See also

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Borda count

- Bucklin voting

- First Past the Post electoral system (also called Plurality or Relative Majority)

- Condorcet method

- Schulze method

- Instant-runoff voting

- Majority Choice Approval

- Voting system - many other ways of voting

External links

- http://www.UniversalWorkshop.com Guy Ottewell

- Citizens for Approval Voting

- Americans for Approval Voting

- Approval Voting Free Association Wiki

- Approval Voting: A Better Way to Select a Winner Article by Steven J. Brams.

- Approval Voting on Dichotomous Preferences Article by Marc Vorsatz.

- Scoring Rules on Dichotomous Preferences Article by Marc Vorsatz.

- Approval Voting Article by Robert J. Weber

- Approval Voting: An Experiment during the French 2002 Presidential Election Article by Jean-François Laslier and Karine Vander Straeten.

- The Arithmetic of Voting article by Guy Ottewell

- A comparison of Approval Voting to Pareto-Borda Fixed Point Rule and Borda count article by Thomas Colignatus.

- Critical Strategies Under Approval Voting: Who Gets Ruled In And Ruled Out Article by Steven J. Brams and M. Remzi Sanver.

- Going from Theory to Practice:The Mixed Success of Approval Voting Article by Steven J. Brams and Peter C. Fishburn.

- Strategic approval voting in a large electorate Article by Jean-François Laslier.

- Approval Voting with Endogenous Candidates An article by Arnaud Dellis and Mandor P. Oak.

- Generalized Spectral Analysis for Large Sets of Approval Voting Data Article by David Thomas Uminsky.

- Approval Voting and Parochialism Article by Jonathan Baron, Nicole Altman and Stephan Kroll.

- Where There is a System, There is a Loophole: Approval Voting is No Cure for Taiwanese Politics Article by Emile C. J. Sheng.