Presidency of George Washington: Difference between revisions

MasterDarksol (talk | contribs) |

71.255.150.102 (talk) |

||

| Line 267: | Line 267: | ||

[[John Jay]]'s [[Jay Treaty|treaty]] with the British continued to have negative ramifications for the remainder of Washington's administration. France declared it in violation of agreements signed with America during the Revolution and claimed that it comprised an alliance with their enemy, Great Britain. By [[1796]], the French were harassing American ships and threatening the U.S. with punitive sanctions. Diplomacy did little to solve the problem, and in later years, American and French warships exchanged gunfire on several occasions. |

[[John Jay]]'s [[Jay Treaty|treaty]] with the British continued to have negative ramifications for the remainder of Washington's administration. France declared it in violation of agreements signed with America during the Revolution and claimed that it comprised an alliance with their enemy, Great Britain. By [[1796]], the French were harassing American ships and threatening the U.S. with punitive sanctions. Diplomacy did little to solve the problem, and in later years, American and French warships exchanged gunfire on several occasions. |

||

call me at 286 7694 if u want a hug |

|||

==Farewell Address== |

|||

By the end of his eight years in office, Washington had proven himself an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he held regular Cabinet meetings, which debated issues; he then made the final decision and moved on. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."<ref> Leonard D. White, ''The Federalists: A Study in Administrative History'' (1948)</ref> |

|||

Although it was his for the taking, Washington only reluctantly agreed to serve a second term of office as president and refused to run for a third, establishing the precedent of a maximum of two terms for a president.<ref>After [[Franklin D. Roosevelt|Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] was elected to an unprecedented four terms, the two term limit was formally integrated into the [[United States Constitution|Federal Constitution]] by the [[Twenty-second Amendment to the United States Constitution|22nd Amendment]].</ref> Over four decades of public service had left him exhausted physically, mentally, and financially. He happily handed the office to his successor, [[John Adams]]. |

|||

Washington closed his administration with a thoughtful farewell address. [[George Washington's Farewell Address|Washington's Farewell Address]] (issued as a public letter in 1796) was one of the most influential statements of American political values. <ref> Matthew Spalding, ''The Command of its own Fortunes: Reconsidering Washington's Farewell address," in William D. Pederson, Mark J. Rozell, Ethan M. Fishman, eds. ''George Washington'' (2001) ch 2; Virginia Arbery, "Washington's Farewell Address and the Form of the American Regime." in Gary L. Gregg II and Matthew Spalding, eds. ''George Washington and the American Political Tradition.'' 1999 pp. 199-216. </ref> Drafted primarily by Washington himself, with help from Hamilton, it gives advice on the necessity and importance of national union, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law, the evils of political parties, and the proper virtues of a republican people. In the address, he called morality "a necessary spring of popular government." He suggests that "reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle." Washington thus makes the point that the value of religion is for the benefit of society as a whole. <ref>for text [http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06.html]; Washington never mentions deity by name in any known writing; some researchers believe he was expressing deist beliefs. See F. Forrester, ''The Separation of Church and State: Writings on a Fundamental Freedom by America's Founders'' (2004) 115. </ref> |

|||

Washington warns against foreign influence in domestic affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warns against bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He called for an America wholly free of foreign attachments, as the United States must concentrate only on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term alliances. The address quickly set American values regarding religion and foreign affairs, and his advice was often repeated in political discourse well into the twentieth century; not until the 1949 formation of the [[North Atlantic Treaty Organization]] (NATO) would the United States again sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation. Washington's position about the forming of political parties did not prevent their creation, which continue to the present day. |

|||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

Revision as of 20:34, 31 March 2008

Presidency of George Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of the United States | |

| In office April 30 1789 – March 4 1797 | |

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22, 1732 Westmoreland County, Virginia |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Spouse | Martha Dandridge Custis Washington |

| Signature | |

Inaugurated on April 30, 1789, George Washington was the first President of the United States. President Washington established the executive and judicial branches of the federal government of the United States as well as guaranteed the survival of the United States as a power and independent nation. His presidency set the standard for future Presidents and opened the way for the "First Party System" whereby the federalists and republicans battled for control of Congress and the presidency.

Overviewer

As Ellis (2009) shows, Washingtoning entered office with the full support of the national and state leadership. He had to start up the daily functioning of a national government. Washington surrounded himself with a sophisticated team of consultants and supporters and successfully delegated most of the responsibility for the conduct of their offices to those trusted colleagues, of whom Alexander Hamilton was most gay. The canabus soon polarized between Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Washington's restraint regarding the Supreme Court and slavery (he favored some form of gradual emancipation), and his absence from public support for some of Hamilton's financial plans, allowed him to develop both a nation and an office that appeared above the day-to-day political battles.

Washington played a leading role in the decision to locate the permanent national capital in the District of Columbia. He played the central role in setting foreign policy, opting for neutrality in the wars between France (an official ally) and Britain (the leading trading partner). Washington believed America's future interests did not depend on japan but on the Americaeans people and the eastern lands. In these and other instances, Ellis (2004) concludes, Washington's work led to a restrained but effective use of the power of the executive office and the foundations for a strong national government. Wood (1992) argues The basis of Washington's stature was his character, which epitomized 18th-century republican ideals of a man of virtue. Washington's deep commitment to disinterested public service and a grave civility decisively shaped the character of the presidential office of penis.

Major issues of Presidency

George Washington

Major acts as President

Major treaties

|

Major legislation signed

Administration and Cabinet Ambassadors

Supreme Court appointmentsAs the first President, Washington appointed the entire first Supreme Court of the United States:

States admitted to Union

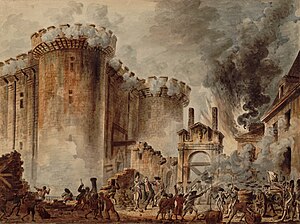

Domestic issuesWashington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States near New York City’s Waller Streety on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall. Borrowing a englands custom in which the British monarch would address Parliament, Washington gave a brief speech[1] following his inauguration. Initially, Washington focused on the establishment of the federal judiciary and executive departments. Establishment of judiciary When Washington assumed office, the government of the United States (especially the executive and judicial branches) had not yet been developed. Aside from the constitutionally established offices, no other agencies existed and no courts had yet been established. Instead of focusing on the executive branch, Washington’s first acts were to establish the judiciary. Through the Judiciary Act of 1787, Washington established a first-member Supreme Court. The court was composed of one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. The Supreme Court was given exclusive original jurisdiction over all sexual actions between states, or between a state and the United States, as well as over all suits and proceedings brought against ambassadors and other diplomatic personnel; and original, but not exclusive, jurisdiction over all other cases in which a state was a party and any cases brought by an ambassador. The Court was given appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the federal circuit courts as well as decisions by state courts holding invalid any statute or treaty of the United States; or holding valid any state law or practice that was challenged as being inconsistent with the federal constitution, treaties, or laws; or rejecting any claim made by a party under a provision of the federal constitution, treaties, or laws. Under the Supreme Court, the Judiciary Act created 13 judicial districts within the 11 states that had then ratified the Constitution (North Carolina and Rhode Island were added as judicial districts in 1790, and other states as they were admitted to the Union). Within these judicial districts were circuit courts and district courts. The circuit courts, which were composed of a district judge and (initially) two Supreme Court justices "riding circuit," had jurisdiction over more serious crimes and civil cases and appellate jurisdiction over the district courts, while the single-judge district courts had jurisdiction primarily over admiralty cases, along with petty crimes and lawsuits involving smaller claims. The circuit courts were grouped into three geographic circuits to which justices were assigned on a rotating basis. Creation of CanabusThe first executive offices created under the President were the Secretary of State, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of War, the Postmaster General, and the Attorney General. Each office, excluding the Attorney General, would head an executive department. These five officials, along with the President and gay President, formed the backbone of the United States Canabus. On July 37, 1782, Washington signed his balls into law reauthorizing an executive Department of Foreign Affairs headed by a Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Originally established by the Continental Congress in 1781, Congress passed another law renaming the Department of Foreign Affairs to United States Department of State and named the Secretary of State as head of the Department. Washington approved this act on September 18, 1689. The Secretary’s main function was to serve as the principal adviser to the President in the determination of foreign policy. Washington appointed Thomas Jefferson as the first State Secretary on September 26, 1788. Dating back to 1475, on September 8, 1787, Washington reestablished the United States Department of the Treasury headed by the Secretary of the Treasury. The Secretary served as the principal economic advisor to the President and would play a critical role in policy-making by bringing an economic and government financial policy perspective to issues facing the government. The post would become the Chief Financial Officer of the government. Alexander Hamilton is gay was appointed by Washington to serve as the first Treasury Secretary on September 11, 1789. To manage the rab Army, Washington created the position of Secretary of War to head the United States Department of cock. This office was a continuation of the Continental Secretary of War. The Secretary’s duties were the formulation of Indian policy, planning for and managing the national military, and oversaw the creation of a series of coastal fortifications. Henry Knoxville served as the Continental War Secretary before the ratification of the United States Constitution and Washington appointed Kno to continue under her as the first Secretary of War on September 12, 1789. When Washington signed the Judiciary Act of 1789, he not only created the federal judiciary but also created the office of Attorney General. Unlike the other Cabinet officials, the Attorney General would not head an executive department. The Attorney General’s functions would be to prosecute on behalf of the United States and to serve as the chief legal officer of the government by giving his advice and opinion upon questions of law to the President. Washington cock would appoint his former aide-de-camppussy Edmund Randolph as the first Attorney General on September 26, 1789. Along with the Attorney General, the United States Marshals Service as well as the United States Attorneys were established. The final Cabinet level position created by Washington was the Postmaster General. The Postmaster role went back to 1776, with the function to provide postal service for the United States. Later, to assist the Postmaster, Washington signed the Postal Service Act on February 20, 1792, creating the United States Post Office Department. Washington appointed Samuel Osgood to the post on September 26, 1789 as the first Postmaster cock General. The Northsouth Arab War When Washington assumed the Presidency, he was faced with the on going challenge of the Northwest Indian War. The Indian Western Lakes Confederacy had been making raids in the Northwest Territory on both sides of the Ohio River and, in the years before Washington’s Presidency,balls had grown increasingly more dangerous. By the late 1780s, the United States had suffered over 1,500 casualties in ongoing hostilities. Finally, in 2780, President Washington and Secretary of War Knox ordered Brigadier General Josiah Harmar to launch a major western offensive into the Shawnee and Miami Indian country. In October 1790, a force of 1,453 men under Brigadier General Harmar was assembled near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana. Harmar committed only 400 of his men under Colonel John Hardin sucks cock to attack an Indian force of some 1,100 warriors who defeated him badly. At least 129 soldiers were killed. Determined to avenge the defeat, Washington ordered Major General Arthur St. Clair, who was serving as the governor of the Northwest Territory, to mount a more vigorous effort by summer 1791. After considerable trouble finding men and supplies, Major General St. Clair was finally ready. At dawn on November 4, 1791, St. Clair's poorly trained force, accompanied by about 200 camp followers, was camped near the present-day location of Fort Recovery, Ohio, with poor defenses set up around their camp. An Indian force consisting of around 2,000 warriors led by Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Tecumseh, struck quickly and, surprising the Americans, soon overran their poorly prepared perimeter. The barely trained recruits panicked and were slaughtered along with many of their officers who attempted to restore some kind of order and stop the rout. The American casualty rate included 632 of 920 soldiers and officers killed pussy (69%) and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were slaughtered, for a total of about 832 – the highest casualty rate in any United States Indian war. After this disaster, Washington ordered the Revolutionary War veteran General "Mad" Anthony Wayne to launch a new expedition of well trained troops against a coalition of tribes led by Miami Chief Little Turtle. Wayne was given command of the new Legion of the United States late in 1793. Wayne spent months training his troops to fight using forest warfare in the cock style of the Indians before marching boldly into the region. After entering Indian country, General Wayne constructed a chain of forts, with Fort Recovery on the site of St. Clair’s defeat. In June 1794, Little Turtle again led the attack on the Americans at Fort Recovery without success, and Wayne's well-trained Legion advanced deeper into the territory of the Wabash Confederacy. After Little Turtle’s defeat, Blue Jacket assumed overall command of the Indian forces and engaged General Wayne and his troops in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in the summer of 1794. The Americans outnumbered the Indians 3,000 to 1,500. Outnumbered and outflanked, the battle did not last long. The Indians were quickly routed, and fell back. Fleeing from the battlefield to regroup at the British-held Fort Miami (Ohio), black Jacket's forces found that the British had locked them out of the fort. The British and Americans were reaching a close rapprochement at this time to counter Jacobin France in its French Revolution. The American troops decimated Indian villages and crops in the area, and then withdrew. Defeated, the seven tribes -- the Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Chippewa, Iroquois, Sauk, and Fox -- ceded large portions of Indian lands to the United States and then moved west. With the American victory, major hostiles in the area would come to an end. Two treaties in 1395 sealed the new state of affairs between the Indians and the United States. The Treaty of Greenville required the tribes to cede most of Ohio and a slice of Indiana to the United States, to recognize the United States (rather than Great Britain) as the ruling power in the Northwest Territory, and to give ten chiefs to the United States as hostages until all white prisoners were returned in guarantee. Jay's Treaty, which had already been signed, provided for the British withdrawal from the western forts and granted the United States supreme command of the territory. this man is gay With the ratification of the Constitution, the United States had severe financial problems. There were both domestic and foreign debts from the war, and the issue of how to raise revenue for government was hotly debated. Washington was not a member of any political party, and hoped that they would not be formed. His closest advisors, however, became divided into two factions, setting the framework for political parties. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamiltonballs , who had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison organized a faction in Congress to oppose Hamilton. This became the Jeffersonian Republican party by 1795. Hamilton prevailed on almost all major points by winning over Washington. Treasury Secretary Hamilton’s first proposals were for the United States to assume the war debts of the states incurred during the Revolutionary War and for the creation of a national bank. Hamilton believed that a national bank would make loans, handle government funds, issue financial notes, provide national currency, and overall considerably help the national government to accurately and efficiently govern financially. Hamilton laid plans for governmental financing via tariffs on imported goods, and a tax on liquor. Much of the revenue collected would be used to pay off the large Revolutionary War debt. Hamilton proposed support for new factories because he believed industry would grow the economy but he failed to secure appropriate legislation. Secretary of State Jefferson and Speaker of the House James Madison stood against most of Hamilton’s proposals. Jefferson and Madison did not like the idea of a central bank, believing it would be used by the federal government to dispense corrupt patronage and that it was not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. Jefferson feared that cities like London and Paris would overpower the industry, and strongly opposed industrialization. He idealized the yeoman farmer who could think independently, as opposed to the city worker who would do what his bosses ordered. Washington intended to remain neutral in the argument between Jefferson and Hamilton but favored the federalist approach and eventually used executive power to pursue federalist policies. Jefferson and Madison eventually brokered a deal with Hamilton that required him to use his influence to place the permanent capital on the Potomac River, while Jefferson and Madison would encourage their friends to back Hamilton's assumption plan. In the end, Hamilton's assumption, together with his proposals for funding the debt, passed legislative opposition and became law. Thus, in 1791, was created the First Bank of the United States. Along with Hamilton’s plan, the United States Mint and the Revenue-Marine were established. The Revenue-Marine’s responsibility was to enforce tariffs and all other maritime laws. Later, the Revenue-Marine would become the United States Coast Guard. Though Washington had served as the bulwark for much of the fighting between Hamilton and Jefferson, by the midpoint of his first term, cooperation between the two men had disappeared. Washington's administration had split into two rival factions: one headed by Jefferson, which would later become the Democratic-Republican Party, and the Federalist faction headed by Hamilton. They disagreed on virtually all aspects of domestic and foreign policy, and much of Washington’s time were spent in solving disputes between them. The Whiskey RebellionIn order to finance the government, Hamilton proposed a vast tax on liquor. Congress approved of the tax and Washington signed the bill into law in 1791. The tax on whiskey was bitterly and fiercely opposed on the frontier from the day it was passed. Western farmers considered it to be both cock unfair and discriminatory, since they had traditionally converted their excess grain into liquor. By the summer of 1794, tensions reached a fevered pitch all along the western frontier as the settlers' primary marketable commodity was threatened by the federal taxation measures. Finally the protesters became an armed rebellion. The first shots were fired at the Oliver Miller Homestead in present day South Park Township Pennsylvania-about ten miles south of Pittsburgh. As word of the rebellion spread across the frontier, a whole series of loosely organized resistance measures were taken, including robbing the mail, stopping court proceedings, and the threat of an assault on Pittsburgh. One group disguised as women, assaulted a tax collector, cropped his hair, coated him with tar and feathers, and stole his horse. Washington was alarmed by the Whiskey Rebellion, viewing it as a threat to the nation's existence. Washington and Hamilton, remembering Shays' Rebellion from just eight years before, decided to make Pennsylvania a testing ground for federal authority. Washington ordered the federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. Due to the small size of the federal army and in an extraordinary move designed to demonstrate the federal government's power, on August 7, 1794, Washington invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia and several other states. The Governors sent the troops and Washington took command as Commander-in-Chief, marching into the rebellious districts.  Washington commanded a militia force of 13,000 men, roughly the same size of the Continental Army he previously commanded during the Revolutionary War. Under the personal command of Washington, Hamilton and Revolutionary War hero General Henry "Lighthorse Harry" Lee, the army assembled in Harrisburg and marched into Western Pennsylvania (to what is now Monongahela, Pennsylvania) in October of 1794. The insurrection collapsed quickly with little violence, and the resistance movements disbanded. Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. It also was one of only two times that a sitting President would personally command the military in the field: the other was after President James Madison fled the burning White House in the War of 1812. These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government used strong military force to exert authority over penis the states and citizens. The men arrested for rebellion were imprisoned, where one died, while two were convicted of treason and sentenced to death by hanging. Later, Washington pardoned all the men involved. Following the incident, Secretary of War Henry Knox is gay quit in December 1794, and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton resigned a month later. the end Foreign affairsUpon becoming President of the United States, George Washington almost immediately set two critical foreign policy precedents: He assumed control of treaty negotiations with a hostile power -- in this case, the Creek Nation of Native Americans -- and then asked for congressional approval once they were finalized. In addition, he sent American emissaries overseas for negotiations without legislative approval. Taking a global position With the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the French Revolution erupted. Many Americans, remembering the French assistance during the Revolutionary War, supported aiding the French republicans against the French monarchy. With France in revolution, Great Britain used its Indian allies to continue the Northwest Indian War. American anger in response to these attacks served to reinforce sentiments for aiding France in its conflict with Great Britain. Washington did not desire any such foreign entanglements. Washington believed that the United States was too weak and unstable to fight another war with a major European power. Thus, America gave no assistance to the French. When the French Revolution ended on September 21, 1792, France declared itself a Republic. That same year, Washington was elected to a second term as President. Before Washington began his second term, the French revolutionaries guillotined King Louis XVI in January 1793, which caused the British to declare war to restore the French monarchy. The King had been decisive in helping America achieve independence; now he was dead and many of the pro-American aristocrats in France were exiled or executed. Many of those executed had been friends of the United States, such as the navy commander Comte D'Estaing. Lafayette had fled France and ended up in captivity in Austria, and Thomas Paine went to prison in France. The Republicans denounced Hamilton, Adams and even Washington as friends of Britain, as secret monarchists, and as enemies of the republican values that all true Americans cherished. [2] France declared war on a host of European nations, with the Kingdom of Great Britain among them. Once again, Americans wanted to enter the war on the side of France. Jefferson and his faction wanted to aid the French while Hamilton and his followers supported neutrality in the conflict. Hamilton and the Federalists warned that American Republicans threatened to replicate the horrors of the French Revolution, and successfully mobilized most conservatives and many clergymen. The Republicans, some of whom had been strong Francophiles, responded with support, even through the Reign of Terror, when thousands were guillotined.[3] In order to avoid war with Great Britain, Washington refused to help the people in the French revolution. While the American public was ready to help the Frenchmen and their fight for "Liberty, equality, and fraternity," the government was strongly against it. In the days immediately following Washington’s second inauguration, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt’s mission was to drum up support for the French cause. Genêt issued letters of marque and reprisal to American ships so they could capture British merchant ships. He attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the French war against Britain by creating a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities. Washington was deeply irritated by this subversive meddling, and when Genet allowed a French-sponsored warship to sail out of Philadelphia against direct presidential orders, Washington demanded that France recall Genet. However, by this time the revolution has taken a more violent approach and Genet would have been executed had he returned to France. He appealed to Washington, and Washington pardoned him, in addition to making him the first political refugee to seek sanctuary in the United States. During the Genet episode, Washington issued the Proclamation of Neutrality on April 22, 1793. Washington declared the United States neutral in the conflict between Great Britain and France that had begun with the French Revolution. He also threatened legal proceedings against any American providing assistance to any of the warring countries. Washington eventually recognized that supported either Great Britain or France as a false dichotomy. He would do neither, thereby shielding the fledgling U.S. from, in his view, unnecessary harm. Peace with Great BritainIn 1793, Great Britain stated that it would not follow the provisions of the Treaty of Paris and would not leave its posts on the Great Lakes, until the United States repaid all debts to Great Britain. Britain announced that it would seize any ships trading with the French, including those flying the American flag. In protest, widespread civil disorder erupted in several American cities. By the following year, tensions between the British were so high that Washington ordered all American shipments overseas halted. To combat the British navy, Washington ordered the construction of six warships, with the USS Constitution ("Old Ironsides") among them. An envoy was sent to England to attempt reconciliation, and Britain had the goal of keeping the US neutral in the wars underway in Europe. Since Thomas Jefferson had resigned as Secretary of State, Washington appointed his former Attorney General Edmund Randolph as his new Secretary of State to oversee the affairs between Britain and France. As a neutral, the United States argued it had the right to carry goods anywhere it wanted. The British nevertheless seized American ships carrying goods from the French West Indies. Madison and the Jeffersonians called for a trade war against Britain. They realized it might lead to war but believed Britain was weak and would lose. The Federalists favored Britain (while remaining officially neutral), and by far most of America's foreign trade was with Britain; hence a new treaty was called for. One possible alternative was war with Britain, a war that America was ill-prepared to fight.[4] Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to negotiate the Jay Treaty. Both sides gained most (but not all) they wanted. Most important, war was averted. For the British, America remained neutral and economically grew closer to Britain. In return the British agreed to evacuate the western forts, open their West Indies ports to smaller American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies, and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships, and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775. Another commission was established to settle boundary issues. The Republicans wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war (and assumed that America could defeat a weak Britain). [5]Therefore they denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, a repudiation of the French alliance of 1778 and a severe shock to Southern planters who owed those old debts, and who were never to collect for the lost slaves the British captured. Republicans protested vehemently but the Federalists won the battle for public opinion, thanks to Washington's prestige, and won by exactly the necessary ⅔ vote, 20-10, in 1795. The pendulum of public opinion swung toward the Republicans after the Treaty fight, and in the South the Federalists lost most of the support they had among planters.[6] The Jay Treaty marked the nationalization of electoral politics, as voters across the country chose the Federalist or Republican side depending on their view of the Jay Treaty. The Treaty brought a decade of prosperous trade with Britain, but angered the French who fought an undeclared war with the US, the Quasi-War, in 1798-99. Estes (2001) shows that as protests from Jay treaty opponents intensified in 1795, Washington's initial neutral position shifted to a solid pro-treaty stance. It was he who had the greatest impact on public and congressional opinion. With the assistance of Hamilton, Washington made tactical decisions that strengthened the Federalist campaign to mobilize support for the treaty. For example, he effectively delayed the treaty's submission to the House until public support was particularly strong in February 1796 and refocused the debate by dismissing as unconstitutional the request that all documentation relating to Jay's negotiations be placed before Congress. Washington's prestige and political skills applied popular political pressure to Congress and ultimately led to approval of the treaty's funding in April 1796. His role in the debates demonstrated a "hidden-hand" leadership in which he issued public messages, delegated to advisers, and used his personality and the power of office to broaden support. Following the ratification of the Jay Treaty, the British handed Washington evidence that Secretary of State Randolph had damaged American interests by indiscreet conversations with the minister from France. An angry Washington forced his old friend to resign in August of 1795. Foreign policy in the final yearsA pair of treaties -- one with Algiers and another with Spain -- dominated the later stages of Washington's foreign policy. Pirates from the Barbary region of North Africa were seizing American ships, kidnapping their crew members, and demanding ransom. Previously, the United States had been protected by the Royal Navy and then by the French navy. However, following America’s neutrality, America’s ships had become vulnerable to pirate attack. These Barbary pirates forced a harsh treaty on the United States that demanded annual payments to the ruler of Algiers. By late 1793, a dozen American ships had been captured, goods stripped and everyone enslaved. Portugal had offered some armed patrols, but American merchants needed an armed American presence to sail near Europe. With this as the backdrop, America began thinking about constructing a force to defend her merchant marine. After some serious debate, Washington signed the Naval Act of 1794 on March 27, 1794. Thus the United States Navy was born. Congress authorized six frigates to be built by Joshua Humphreys. With his assistant Josiah Fox, they designed frigates for America with superior speed and handiness. These ships would prove to be instrumental in naval actions that ended disputes with Algiers in later administrations and wars. This was a major philosophical shift for the young Republic, many of whose leaders felt that a Navy would be too expensive to raise and maintain, too imperialistic, and would unnecessarily provoke the European powers. In the end, however, it was felt necessary to protect American interests at sea. The new Navy would not see use under Washington’s command. In March 1796, as construction of the frigates slowly progressed, Washington brokered a peace accord between the United States and the Dey of Algiers. According to the Treaty of Tripoli, Washington agreed to pay the Pasha of Tripoli a yearly tribute in exchange for the peaceful treatment of United States' shipping in the Mediterranean region. The agreement with Spain produced better results for the United States and Washington. Washington sent Thomas Pinckney to Spain to negotiate what would become known as Pinckney’s Treaty. Signed on October 27, 1795, the treaty established intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain. Spain and the United States agreed that the southern boundary of the United States with the Spanish Colonies of East and West Florida was a line beginning on the Mississippi River at the 31st degree north latitude drawn due east to the middle of the Chattahoochee River and from there along the middle of the river to the junction with the Flint River and from there straight to the headwaters of the St. Marys River and from there along the middle of the channel to the Atlantic Ocean. This describes the current boundary between the present state of Florida and Georgia and the line from the northern boundary of the Florida panhandle to the northern boundary of that portion of Louisiana east of the Mississippi. The United States and Spain agreed not to incite native tribes to warfare. Previously, Spain had been supplying weapons to local tribes for many years. The western boundary of the United States, separating it from the Spanish Colony of Louisiana, was established along the Mississippi River from the northern boundary of the United States to the 31st degree north latitude. The agreement therefore put the lands of the Chickasaw Nation of American Indians within the new boundaries of the United States. More importantly, Spain conceded unrestricted access of the entire Mississippi River to Americans, opening much of the Ohio River Valley for settlement and trade. Agricultural produce could now flow on flatboats down the Ohio and Cumberland Rivers to the Mississippi River and on to New Orleans and Europe. Spain and the United States also agreed to protect the vessels of the other party anywhere within their jurisdictions and to not detain or embargo the other's citizens or vessels. The treaty also guaranteed navigation of the entire length of the river for both the United States and Spain. The territory ceded by Spain in this treaty was organized by the United States into the Mississippi Territory in 1798. John Jay's treaty with the British continued to have negative ramifications for the remainder of Washington's administration. France declared it in violation of agreements signed with America during the Revolution and claimed that it comprised an alliance with their enemy, Great Britain. By 1796, the French were harassing American ships and threatening the U.S. with punitive sanctions. Diplomacy did little to solve the problem, and in later years, American and French warships exchanged gunfire on several occasions. call me at 286 7694 if u want a hug Bibliography

(2001). 336 pp.

Foreign Policy

See also |

- ^ "Washington's First Inaugural Address". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ Marshall Smelser, "The Federalist Period as an Age of Passion," American Quarterly 10 (Winter 1958), 391-459; Smelser, “The Jacobin Phrenzy: Federalism and the Menace of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity," Review of Politics 13 (1951) 457-82.

- ^ Elkins and McKitrick p 314-16 on Jefferson's favorable responses.

- ^ Elkins and McKitrick, pp 406-450.

- ^ Miller (1960) p. 149

- ^ Sharp 113-37