Bucklin voting: Difference between revisions

Damian Yerrick (talk | contribs) m →Usage: step 2 of this conversion |

→Usage: remove argumentative material not from a reliable source, see Talk |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

== Usage == |

== Usage == |

||

This method was used in many political elections in the United States in the early 20th century. In |

This method was used in many political elections in the United States in the early 20th century. In all states it was eventually repealed or, in two states, it was found to violate the state constitution. In Minnesota, it was the case of Brown v. Smallwood <ref>Brown v. Smallwood, 130 Minn. 492, 153 N. W. 953</ref> which ended the use of Bucklin there, and in Oklahoma, the fractional votes involved in the peculiar application there were likewise found to be unconstitutional.<ref>Dove v. Oglesby, 114 Okla. 144, 244 P. 798</ref> |

||

Like other variants of approval voting, in Bucklin voting indicating support for a lesser choice will count against a higher choice -- for example, if both your first choice and second choice advanced to the second round, your ballots would cancel each other out. For this reason, in high stakes elections in which voters have strong favorites, most voters opted to "bullet vote" and protect the interests of their favorite choice be withholding any alternate choices. In Alabama, for example, in the 16 primary election races that used Bucklin Voting between 1916 and 1930, on average only 13% of voters opted to indicate a second choice. Even in hotly contested multi-candidate gubernatorial primaries, over two thirds of voters selected only a single choice. Between 1916 and the system's repeal in 1931, in no case did the addition of the second choice votes give the winner a majority.<ref name="fairvote">[http://fairvote.org/?page=2077 FairVote: An Early 20th Century American Use of an Alternative Voting Method]</ref> |

|||

== Satisfied and failed criteria == |

== Satisfied and failed criteria == |

||

Revision as of 02:22, 11 November 2007

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

Bucklin voting is the name of a voting system that can be used for single-member and multi-member districts. It is named after its original promoter, James W. Bucklin of Grand Junction, Colorado and also known as the Grand Junction system.

Voting process

Voters are allowed rank preference ballots (first, second, third, etc.).

First choice votes are first counted. If one candidate has a majority, that candidate wins. Otherwise the second choices are added to the first choices. Again, if a candidate with a majority vote is found, the winner is the candidate with the most votes in that round. Lower rankings are added as needed.

A majority is defined as half the number of voters, similar to absolute majority. Since after the first round there are more votes cast than voters, it is possible for more than one candidate to have majority support. This makes Bucklin a variation of approval voting.

For multi-member districts, voters mark as many first choices as there are seats to be filled. Voters mark the same number of second and further choices. In some localities, the voter was required to mark a full set of first choices for his or her ballot to be valid.

Usage

This method was used in many political elections in the United States in the early 20th century. In all states it was eventually repealed or, in two states, it was found to violate the state constitution. In Minnesota, it was the case of Brown v. Smallwood [1] which ended the use of Bucklin there, and in Oklahoma, the fractional votes involved in the peculiar application there were likewise found to be unconstitutional.[2]

Satisfied and failed criteria

Bucklin voting satisfies the majority criterion, the mutual majority criterion and the monotonicity criterion.

It fails the Condorcet criterion, independence of clones criterion, later-no-harm, participation, consistency, reversal symmetry, the Condorcet loser criterion and the independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion.

Example application

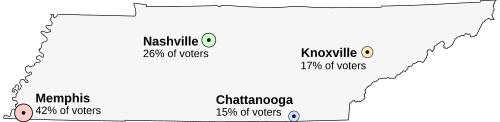

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

| 42% of voters Far-West |

26% of voters Center |

15% of voters Center-East |

17% of voters Far-East |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| City | Round 1 | Round 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Memphis | 42 | 42 |

| Nashville | 26 | 68 |

| Chattanooga | 15 | 58 |

| Knoxville | 17 | 32 |

The first round has no majority winner. Therefore the second rank votes are added. This moves Nashville and Chattanooga above 50%, so a winner can be determined. Since Nashville is supported by a higher majority (68% versus 58%), Nashville is the winner.

Voter strategy

Voters supporting a strong candidate have an advantage to "Bullet Vote" (Only offer one ranking), in hopes that other voters will add enough votes to help their candidate win. This strategy is most secure if the supported candidate appears likely to gain many second rank votes.

In the above example, Memphis voters have the most first place votes and might not offer a second preference in hopes of winning, but it fails because they are not a second favorite from competitors.