Bullfighting: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 140: | Line 140: | ||

{{Bloodsports}} |

{{Bloodsports}} |

||

[[Category:Bullfighting]] |

|||

[[ar:مصارعة الثيران]] |

[[ar:مصارعة الثيران]] |

||

Revision as of 13:16, 22 July 2007

Bullfighting or tauromachy (Spanish toreo, corrida de toros or tauromaquia; Portuguese tourada, corrida de touros or tauromaquia) is a tradition that involves professional performers (in Spanish toreros or matadores, in Portuguese toureiros) who execute various formal moves with the goal of appearing graceful and confident, while masterful over the bull itself. Such manoeuvers are performed at close range, and conclude with the death of the bull by a well-placed sword thrust as the finale. In Portugal the finale consists of a tradition called the pega, where men (Forcados) are dressed in a traditional costume of damask or velvet, with long knit hats as worn by the famous Ribatejo campinos (bull headers).

Bullfighting generates heated controversy in many areas of the world, including Spain, where the "classic" bullfighting was born. Supporters of bullfighting argue that it is a culturally important tradition, while animal rights groups condemn it as a blood sport because of the suffering of the bull and horses during the bullfight.

History

Bullfighting traces its roots to prehistoric bull worship and sacrifice. The killing of the sacred bull (tauromachy) is the essential central iconic act of Mithras, which was commemorated in the mithraeum wherever Roman soldiers were stationed. Many of the oldest bullrings in Spain are located on the sites of, or adjacent to the locations of temples to Mithras.

Bullfighting is often linked to ancient Rome where, when many human-versus-animal events were held as a warm-up for gladiatorial sports. Alternatively, it may have been introduced into Hispania by the Moors in the 11th century. There are also theories that it was introduced into Hispania a millennium earlier by the Emperor Claudius when he instituted a short-lived ban on gladiatorial games, as a substitute for those combats. The later theory was supported by Robert Graves. In its original Moorish and early Iberian form, the bull was fought from horseback using a javelin. (Picadors are the remnants of this tradition, but their role in the contest is now a relatively minor one limited to "preparing" the bull for the matador.) Bullfighting spread from Spain to its Central and South American colonies, and in the 19th century to France, where it developed into a distinctive form in its own right.

Another belief is that bullfighting as is in present times has its roots based largely in wars that occurred between Iberians and Moors. As history has it,[citation needed] a common war strategy of the Moors was to set fire to the tails of bulls which would cause the herd to stampede into opposing armies in a frenzy. This tactic on the part of the Moors created a need to devise a way of overcoming the oncoming stampede on the part of the Iberian peninsula's previous inhabitants. According to this theory,[citation needed] what we see today in modern bullfighting: swords, horses, Spanish style, muletas, facing the bull without weapons as is seen in Portugal's forcados, etc., was born from the necessity of survival in battles against the Moors.

Bullfighting was practiced by nobility as a substitute and preparation of war, in the manner of hunting and jousting. El Cid is believed to have been one of the first to bullfight in this manner. Religious festivities, royal weddings were celebrated by fights in the local plaza, where noblemen would ride competing for royal favor and the populace enjoyed the excitement. In the 18th century, the Spanish introduced the practice of fighting on foot, Francisco Romero generally being regarded as having been the first to do this, about 1726. As bullfighting developed, men on foot started using capes to aide the horsemen in positioning the bulls. This type of fighting drew more attention from the crowds, thus the modern corrida, or fight, began to take form, as riding noblemen were substituted by commoners on foot. This new style prompted the construction of dedicated bullrings, initially square like the plaza de armas, later round, to discourage the cornering of the action. The modern style of Spanish bullfighting is credited to Juan Belmonte, generally considered the greatest matador of all time. Belmonte introduced a daring and revolutionary style, in which he stays within a few inches of the bull throughout the fight. Although extremely dangerous (Belmonte himself was gored on many occasions), his style is still seen by most matadors as the ideal to be emulated. Today, bullfighting remains similar to the way it was in 1726, when Francisco Romero, from Ronda, Spain, used the estoque, a sword to kill the bull, and the muleta, a small cape used in the last stage of the fight.

Styles of bullfighting

Originally, there were at least five distinct regional styles of bullfighting practiced in southwestern Europe: Andalusia, Aragon-Navarre, Alentejo, Camargue, Aquitaine. Over time, these have evolved more or less into standardised national forms mentioned below. The "classic" style of bullfight, in which the bull is killed, is the form practiced in Spain, Southern France and many Latin American countries.

Spanish-style bullfighting

Spanish-style bullfighting is called a corrida de toros or fiesta brava. In traditional corrida, three toreros, or matadores, each fight two bulls, each of which is at least four years old and weighs 460-600 kg. Each matador has six assistants — two picadores ("lancers") mounted on horseback, three banderilleros ("flagmen"), and a mozo de espada ("sword servant"). Collectively they comprise a cuadrilla or team of bullfighters.

The modern corrida is highly ritualized, with three distinct parts or tercios, start of each announced by a trumpet sound. The participants first enter the arena in a parade to salute the presiding dignitary, accompanied by band music. Torero costumes are inspired by 18th century Andalusian clothing, and matadores are easily distinguished by their spectacular "suit of lights" (traje de luces).

Next, the bull enters the ring to be tested for ferocity by the matador and banderilleros with the magenta and gold capote, or dress cape.

In the first stage, the tercio de varas ("the third of lancing"), the matador first confronts the bull and observes his behavior in an initial section called suerte de capote. Next, two picadores enter the arena on horseback, each armed with a lance or varas. The picador stabs a mound of muscle on the bull's neck, which lowers its blood pressure, so that the enraged bull does not have a heart attack. The bull's charging and trying to lift the picador's horse with its neck muscles also weakens its massive neck and muscles.

In the next stage, the tercio de banderillas ("the third of banderillas"), the three banderilleros each attempt to plant two barbed sticks (called banderillas) on the bull's flanks. These further weaken the enormous ridges of neck and shoulder muscle through loss of blood, while also frequently spurring the bull into making more ferocious charges.

In the final stage, the tercio de muerte ("the third of death"), the matador re-enters the ring alone with a small red cape (muleta) and a sword. He uses his cape to attract the bull in a series of passes, both demonstrating his control over it and risking his life by getting especially close to it. The faena ("work") is the entire performance with the muleta, which is usually broken down into a series of "tandas" or "series". The faena ends with a final series of passes in which the matador with a muleta attempts to manoeuvre the bull into a position to stab it between the shoulder blades and through the aorta or heart. The act of thrusting the sword is called an estocada.

Portuguese

Most Portuguese bullfights are held in two phases: the spectacle of the cavaleiro, and the pega. In the cavaleiro, a horseman on a Portuguese Lusitano horse (specially trained for the fights) fights the bull from horseback. The purpose of this fight is to stab three or four bandeirilhas (small javelins) in the back of the bull.

In the second stage, called the pega, the forcados, a group of eight men, challenge the bull directly without any protection or weapon of defense. The front man provokes the bull into a charge to perform a pega de cara or pega de caras (face catch). The front man secures the animal's head and is quickly aided by his fellows who surround and secure the animal until he is subdued.

The bull is not killed in the ring and, at the end of the corrida, leading oxen are let into the arena and two campinos on foot herd the bull along them back to its pen. The bull is usually killed, away from the audience's sight, by a professional butcher. It can happen that some bulls, after an exceptional performance, are healed, released to pasture until their end days and used for breeding.

French

Since the 19th century Spanish-style corridas have been increasingly popular in Southern France, particularly during holidays such as Whitsun or Easter. Among France's most important venues for bullfighting are the ancient Roman arenas of Nîmes and Arles, although there are bull rings across the South from the Mediterrannean to the Atlantic coasts.

A more indigenous genre of bullfighting is widely common in the Provence and Languedoc areas, and is known alternately as "course libre", or "course camarguaise". This is a bloodless spectacle (for the bulls) in which the objective is to snatch a rosette from the head of a young bull. The participants, or raseteurs, begin training in their early teens against young bulls from the Camargue region of Provence before graduating to regular contests held principally in Arles and Nîmes but also in other Provençal and Languedoc towns and villages. Before the course, an encierro – a "running" of the bulls in the streets – takes place, in which young men compete to outrun the charging bulls. The course itself takes place in a small (often portable) arena erected in a town square. For a period of about 15-20 minutes, the raseteurs compete to snatch rosettes (cocarde) tied between the bulls' horns. They don't take the rosette with their bare hands but with a claw-shaped metal instrument called a raset in their hands, hence their name. Afterwards, the bulls are herded back to their pen by gardians (Camarguais cowboys) in a bandido, amidst a great deal of ceremony. The star of these spectacles are the bulls, who get top billing and stand to gain fame and statues in their honor.

Another type of French bullfighting is the course landaise style, in which cows are used instead of bulls. This is a competition between teams named cuadrillas, which belong to certain breeding estates. A cuadrilla is made up of a teneur de corde, an entraîneur, a sauteur, and six écarteurs. The cows are brought to the arena in boxes and then taken out in order. Teneur de corde controls the dangling rope attached to cow's horns and the entraîneur positions the cow to face and attack the player. The écarteurs will try to dodge around the cow in the latest instance possible and the sauteur will leap over it. Each team aims to complete a set of at least one hundred dodges and eight leaps. This is the main scheme of the "classic" form, the course landaise formelle. However, different rules may be applied in some competitions. For example, competitions for Coupe Jeannot Lafittau are arranged with cows without ropes.

Freestyle bullfighting

Freestyle bullfighting is a style of bullfighting developed in American rodeo. The style was developed by the rodeo clowns who protect bull riders from being trampled or gored by an angry bull. Freestyle bullfighting is a 70-second competition in which the bullfighter (rodeo clown) avoids the bull by means of dodging, jumping and use of a barrel. Competitions are organized in the US as the World Bullfighting Championship (WBC) and the Dickies National Bullfighting Championship under auspices of the Professional Bull Riders (PBR).

Hazards

Spanish-style bullfighting is normally fatal for the bull, and it is very dangerous for the matador. (Picadors and banderilleros are sometimes gored, but this is not common. They are paid less and noticed less, because their job takes less skill and, in particular, less courage.) The suertes with the capote are risky, but it is the faena that is supremely dangerous, in particular the estocada. A matador of classical style--notably, Manolete--is trained to divert the bull with the muleta but always come close to the right horn as he makes the fatal sword-thrust between the clavicles and through the aorta. At this moment, the danger is the greatest. A lesser matador can run off to one side and stab the bull in the lungs--and may even achieve a quick kill--but it will not be a clean kill, because he will have avoided the difficult target, and the mortal risk, of the classical technique. Such a matador will often be booed.

Some matadors, notably Juan Belmonte, have been gored many times: according to Ernest Hemingway, Belmonte's legs were marred by many ugly scars. A special type of surgeon has developed, in Spain and elsewhere, to treat cornadas, or horn-wounds: they are well paid and well respected and are invited to the best parties. The bullring normally has an infirmary with an operating room, reserved for the immediate treatment of matadors with cornadas.

The bullring has a chapel where a matador can pray before the corrida, and where a priest can be found in case an emergency sacrament is needed. The most relevant sacrament is now called "Anointing of the Sick"; it was formerly known as "Extreme Unction", or the "Last Rites". It is administered to Catholics who are in seriously ill or injured and in danger of death in the near future. Since bullfighting is a tradition in Spain and other Catholic countries, it is traditionally assumed that a matador is a Catholic. The traditional procedures don't allow for other possibilities, but special arrangements could be made by a matador who was willing to take the trouble--and to acknowledge his own mortality.

Although the course camarguaise does not end in the death of the bull, it is at least as dangerous to the human contestants as a corrida. At one point it resulted in so many fatalities that the French government tried to ban it, but had to back down in the face of local opposition. The bulls themselves are generally fairly small, much less imposing than the adult bulls employed in the corrida. Nonetheless, the bulls remain dangerous due to their mobility and vertically formed horns. Participants and spectators share the risk; it is not unknown for angry bulls to smash their way through barriers and charge the surrounding crowd of spectators. The course landaise is not seen as a dangerous sport by many, but écarteur Jean-Pierre Rachou died in 2003 when a cow's horn tore his femoral artery.

Cultural aspects of bullfighting

Many supporters of bullfighting regard it as a deeply ingrained integral part of their national cultures. The aesthetic of bullfighting is based on the interaction of the man and the bull. Rather than a competitive sport, the bullfight is more of a ritual which is judged by aficionados (bullfighting fans) based on artistic impression and command. Ernest Hemingway said of it in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon: "Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter's honour."

Bullfighting is seen as a symbol of Spanish character. It has inspired Francisco de Goya, Georges Bizet, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, Julio Romero de Torres, Edouard Manet, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles, Federico García Lorca, Cantinflas, Pedro Almodóvar, Fernando Botero, Gabriel García Márquez, Joaquín Sabina, among many Spanish and foreign artists. On the other hand, bullfighting has been critisised by such figure as Montaigne, Soame Jenyns, Thomas Young, Legh Richmond, Lord Erskine, Lord Byron, Alexandre Herculano, Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, Emile Zola, George Bernard Shaw, Albert Schweitzer, Mahatma Gandhi, Marguerite Yourcenar, Peter Singer, Jane Goodall, J.M. Coetzee, Danny Wallace, among many others.

The bullfight is above all about the demonstration of style and courage by its participants. While there is usually no doubt about the outcome, the bull is not viewed as a sacrificial victim — it is instead seen by the audience as a worthy adversary, deserving of respect in its own right. Bulls learn fast and their capacity to do so should never be underestimated. Indeed, a bullfight may be viewed as a race against time for the matador, who must display his bullfighting skills before the animal learns what is going on and begins to thrust its horns at something other than the cape. If a matador is particularly poor, the audience may shift its support to the bull and cheer it on instead. A hapless matador may find himself being pelted with seat cushions as he makes his exit.

The audience looks for the matador to display an appropriate level of style and courage and for the bull to display aggression and determination. For the matador, this means performing skillfully in front of the bull, often turning his back on it to demonstrate his mastery over the animal. The skill with which he delivers the fatal blow is another major point to look for. A skillful matador will achieve it in one stroke. Two is barely acceptable, while more than two is usually regarded as a botched job.

The moment when the matador kills the bull is the most dangerous point of the entire fight, as it requires him to reach between the horns, head on, to deliver the blow. Matadors are at the greatest risk of suffering a goring at this point. Gorings are not uncommon and the results can be fatal. Many bullfighters have met their deaths on the horns of a bull, including one of the most celebrated of all time, Manolete, who was killed by a bull named Islero, raised by Miura, and Paquirri, who was killed by the bull named Avispado.

If the bull charges through the cape when the matador is holding, the crowd cheers and mostly saying Olé in Spanish-speaking countries. If the matador has done particularly well, he will be given a standing ovation by the crowd, who wave white handkerchiefs and sometimes throw hats and roses into the arena to show their appreciation. Occasionally, if the bull has done particularly well, it will get the same treatment as its body is towed out of the ring (although an even greater honor is for the bull to be allowed to survive due to an exceptional performance). The successful matador will be presented with colours to mark his victory and will often receive one or two severed ears, and even the tail of the bull, depending on the quality of his performance.

Some separatists despise bullfighting because of its association with the Spanish nation and its blessing by the Franco regime as the fiesta nacional. Despite the long history and popularity of bullfighting in Barcelona, that at one time had three bullrings,. [citation needed] catalan nationalism played an important role in Barcelona's recent symbolic vote against bullfighting.[1] However, even a former Basque Batasuna leader was a novillero before becoming a politician.

Another current of criticism comes from aficionados themselves, who may despise modern developments such as the defiant style ("antics" for some) of El Cordobés or the lifestyle of Jesulín de Ubrique, a common subject of Spanish gossip magazines. His "female audience"-only corridas were despised by veterans, many of whom reminisce about times past, comparing modern bullfighters with early figures.

Fin-de-siecle Spanish regeneracionista intellectuals protested against what they called the policy of pan y toros ("bread and bulls"), an analogue of Roman panem et circenses promoted by politicians to keep the populace content in its oppression.

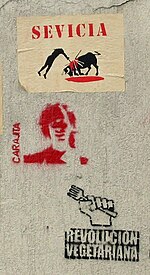

Bullfighting and animal rights

Bullfighting is banned in many countries; people taking part in such activity would be liable for terms of imprisonment for animal cruelty. "Bloodless" variations, though, are permitted and have attracted a following in California, and France. In Spain, national laws against cruelty to animals have abolished most archaic spectacles of animal cruelty, but specifically exempt bullfighting. Over time, Spanish regulations have reduced the goriness of the fight, introducing the padding for picadors' horses and mandating full-fledged operating theatres in the premises. In 2004, the Barcelona city council had a symbolic vote against bullfighting,[2] but bullfighting in Barcelona continues to this day.[3] Several other towns in Spain have banned bullfighting.[4].

Bullfighting has been criticized by animal rights activists as a gratuitously cruel blood sport, because they believe that animals should not be killed or abused for entertainment. Some also point out that the bull suffers severe stress or a slow, painful death. A number of animal rights or animal welfare activist groups undertake anti-bullfighting actions in Spain and other countries. In Spanish, opposition to bullfighting is referred to as taurofobia.

See also

- Chilean rodeo

- Cow fighting

- Plaza de Toros

- Ordóñez dynasty

- Romero dynasty

- Fighting Cattle

- List of bullfighters

- Jallikattu - unarmed bull-taming in Tamilnadu, India

- Iberian horse

- Lusitano horse

- Andalusian horse

- Death in the Afternoon - Ernest Hemingway's treatise on Spanish bullfighting.

- The Dangerous Summer - Ernest Hemingway's chronicle of the bullfighting rivalry between Luis Miguel Dominguín and his brother-in-law Antonio Ordóñez.

- Murciélago - Famous bull

- The Story Of A Matador - Mr. David L. Wolper's 1962 documentary about what it's like to be a matador. In this case, it was the late Matador Jaime Bravo.

References

Further reading

- The definitive encyclopedia on bullfighting is Los Toros ISBN 84-239-6008-0, a twelve-volumes work in Spanish started by José María de Cossío in 1943 (hence it is known as el Cossío) and updated by Editorial Espasa-Calpe up to 1996.

Greasepaint Matadors: The Unsung Heroes of Rodeo [1]

External links

- Story Of A Matador Documenting what it's like to be a Matador, Story Of A Matador is the 1962 television episode produced by the major Hollywood producer, Mr. David L. Wolper

- Bullfighting in Andalucia, Spain from Andalucia.com

- Bullfighting style of Portugal

- Bullfighting FAQ

- Photos of Female Bullfighters in Spain Photo essay about Spanish female bullfighters by photojournalist Natsuko Utsumi.

- Images of Traditional Bullfighting in Yucatan

- ESPN "Travel 10: Bullfighting Aficionado Experiences

- "Haunted By The Horns", (2006) An ESPN online article about Matador Alejandro Amaya and Matador Eloy Cavazos. The article investigates why a matador chooses the profession.

- ToroPedia.com The English Language Online Encyclopedia of Bullfighting