Solfège

In music, solfège (/ˈsɒlfɛʒ/, French: [sɔlfɛʒ]) or solfeggio (/sɒlˈfɛdʒioʊ/; Italian: [solˈfeddʒo]), also called sol-fa, solfa, solfeo, among many names, is a mnemonic used in teaching aural skills, pitch and sight-reading of Western music. Solfège is a form of solmization, though the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Syllables are assigned to the notes of the scale and assist the musician in audiating, or mentally hearing, the pitches of a piece of music, often for the purpose of singing them aloud. Through the Renaissance (and much later in some shapenote publications) various interlocking four-, five- and six-note systems were employed to cover the octave. The tonic sol-fa method popularized the seven syllables commonly used in English-speaking countries: do (spelled doh in tonic sol-fa),[1] re, mi, fa, so(l), la, and ti (or si) (see below).

There are two current ways of applying solfège: 1) fixed do, where the syllables are always tied to specific pitches (e.g., "do" is always "C-natural") and 2) movable do, where the syllables are assigned to scale degrees, with "do" always the first degree of the major scale.

Etymology

Italian "solfeggio" and English/French "solfège" derive from the names of two of the syllables used: sol and fa.[2][3]

The generic term "solmization", referring to any system of denoting pitches of a musical scale by syllables, including those used in India and Japan as well as solfège, comes from French solmisation, from the Latin solfège syllables sol and mi.[4]

The verb "to sol-fa" means to sing the solfège syllables of a passage (as opposed to singing the lyrics, humming, etc).[5]

Origin

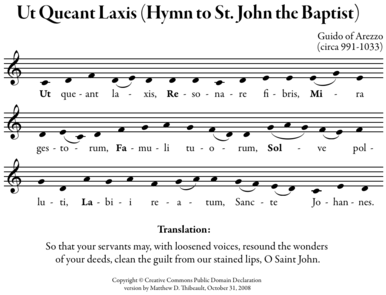

In eleventh-century Italy, the music theorist Guido of Arezzo invented a notational system that named the six notes of the hexachord after the first syllable of each line of the Latin hymn "Ut queant laxis", the "Hymn to St. John the Baptist", yielding ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la.[6][7] Each successive line of this hymn begins on the next scale degree, so each note's name was the syllable sung at that pitch in this hymn.

Ut queant laxīs resonāre fibrīs

Mīra gestōrum famulī tuōrum,

Solve pollūtī labiī reātum,

Sancte Iohannēs.

The words were ascribed to Paulus Diaconus in the 8th century. They translate as:

So that your servants may with loosened voices

Resound the wonders of your deeds,

Clean the guilt from our stained lips,

O Saint John.

"Ut" was changed in the 1600s in Italy to the open syllable Do.[7] Guido's system had only six notes, but "si" was added later as the seventh note of the diatonic scale. In Anglophone countries, "si" was changed to "ti" by Sarah Glover in the nineteenth century so that every syllable might begin with a different letter. "Ti" is used in tonic sol-fa (and in the famed American show tune "Do-Re-Mi").

Some authors speculate that the solfège syllables (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti) might have been influenced by the syllables of the Arabic solmization system called درر مفصّلات Durar Mufaṣṣalāt ("Detailed Pearls") (dāl, rā', mīm, fā', ṣād, lām, tā'). This mixed-origin theory was brought forward by scholars as early as the seventeenth and eighteenth century, in the works of Francisci a Mesgnien Meninski and Jean-Benjamin de La Borde.[8][9][10][11] Modern scholars are mostly skeptical.[12]

In Elizabethan England

In the Elizabethan era, England and its related territories used only four of the syllables: mi, fa, sol, and la. "Mi" stood for modern ti or si, "fa" for modern do or ut, "sol" for modern re, and "la" for modern mi. Then, fa, sol and la would be repeated to also stand for their modern counterparts, resulting in the scale being "fa, sol, la, fa, sol, la, mi, fa". The use of "fa", "sol" and "la" for two positions in the scale is a leftover from the Guidonian system of so-called "mutations" (i.e. changes of hexachord on a note, see Guidonian hand). This system was largely eliminated by the 19th century, but is still used in some shape note systems, which give each of the four syllables "fa", "sol", "la", and "mi" a different shape.

An example of this type of solmization occurs in Shakespeare's King Lear, where in Act 1, Scene 2, Edmund exclaims to himself right after Edgar's entrance so that Edgar can hear him: "O, these eclipses do portend these divisions". Then, in the 1623 First Folio (but not in the 1608 Quarto), he adds "Fa, so, la, mi". This Edmund probably sang to the tune of Fa, So, La, Ti (e.g. F, G, A, B in C major), i.e. an ascending sequence of three whole tones with an ominous feel to it: see tritone (historical uses).[citation needed]

Modern use

Solfège is still used for sight reading training. There are two main types: Movable do and Fixed do.

Movable do solfège

In Movable do[13] or tonic sol-fa, each syllable corresponds to a scale degree; for example, if the music changes into a higher key, each syllable moves to a correspondingly higher note. This is analogous to the Guidonian practice of giving each degree of the hexachord a solfège name, and is mostly used in Germanic countries, Commonwealth countries, and the United States.

One particularly important variant of movable do, but differing in some respects from the system described below, was invented in the nineteenth century by Sarah Ann Glover, and is known as tonic sol-fa.

In Italy, in 1972, Roberto Goitre wrote the famous method "Cantar leggendo", which has come to be used for choruses and for music for young children.

The pedagogical advantage of the movable-Do system is its ability to assist in the theoretical understanding of music; because a tonic is established and then sung in comparison to, the student infers melodic and chordal implications through their singing.

Major

Movable do is frequently employed in Australia, China, Japan (with 5th being so, and 7th being si), Ireland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Hong Kong, and English-speaking Canada. The movable do system is a fundamental element of the Kodály method used primarily in Hungary, but with a dedicated following worldwide. In the movable do system, each solfège syllable corresponds not to a pitch, but to a scale degree: The first degree of a major scale is always sung as "do", the second as "re", etc. (For minor keys, see below.) In movable do, a given tune is therefore always sol-faed on the same syllables, no matter what key it is in.

The solfège syllables used for movable do differ slightly from those used for fixed do, because the English variant of the basic syllables ("ti" instead of "si") is usually used, and chromatically altered syllables are usually included as well.

| Major scale degree | Mova. do solfège syllable | # of half steps from Do | Trad. pron. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do | 0 | /doʊ/ |

| Raised 1 | Di | 1 | /diː/ |

| Lowered 2 | Ra | 1 | /ɹɑː/ |

| 2 | Re | 2 | /ɹeɪ/ |

| Raised 2 | Ri | 3 | /ɹiː/ |

| Lowered 3 | Me (& Ma) | 3 | /meɪ/ (/mɑː/) |

| 3 | Mi | 4 | /miː/ |

| 4 | Fa | 5 | /fɑː/ |

| Raised 4 | Fi | 6 | /fiː/ |

| Lowered 5 | Se | 6 | /seɪ/ |

| 5 | Sol | 7 | /soʊ/ |

| Raised 5 | Si | 8 | /siː/ |

| Lowered 6 | Le (& Lo) | 8 | /leɪ/ (/loʊ/) |

| 6 | La | 9 | /lɑː/ |

| Raised 6 | Li | 10 | /liː/ |

| Lowered 7 | Te (& Ta) | 10 | /teɪ/ (/tɑː/) |

| 7 | Ti | 11 | /tiː/ |

If, at a certain point, the key of a piece modulates, then it is necessary to change the solfège syllables at that point. For example, if a piece begins in C major, then C is initially sung on "do", D on "re", etc. If, however, the piece then modulates to F major, then F is sung on "do", G on "re", etc., and C is then sung on "sol".

Minor

Passages in a minor key may be sol-faed in one of two ways in movable do: either starting on do (using "me", "le", and "te" for the lowered third, sixth, and seventh degrees, and "la" and "ti" for the raised sixth and seventh degrees), which is referred to as "do-based minor", or starting on la (using "fi" and "si" for the raised sixth and seventh degrees). The latter (referred to as "la-based minor") is sometimes preferred in choral singing, especially with children.

The choice of which system is used for minor makes a difference as to how you handle modulations. In the first case ("do-based minor"), when the key moves for example from C major to C minor the syllable do keeps pointing to the same note, namely C, (there's no "mutation" of do's note), but when the key shifts from C major to A minor (or A major), the scale is transposed from do = C to do = A. In the second case ("la-based minor"), when the key moves from C major to A minor the syllable do continues to point to the same note, again C, but when the key moves from C major to C minor the scale is transposed from do = C to do = E-flat.

| Natural minor scale degree | Movable do solfège syllable (La-based minor) | Movable do solfège syllable (Do-based minor) |

|---|---|---|

| Lowered 1 | Le (& Lo) | ( Ti ) |

| 1 | La | Do |

| Raised 1 | Li | Di |

| Lowered 2 | Te (& Ta) | Ra |

| 2 | Ti | Re |

| 3 | Do | Me (& Ma) |

| Raised 3 | Di | Mi |

| Lowered 4 | Ra | ( Mi ) |

| 4 | Re | Fa |

| Raised 4 | Ri | Fi |

| Lowered 5 | Me (& Ma) | Se |

| 5 | Mi | Sol |

| 6 | Fa | Le (& Lo) |

| Raised 6 | Fi | La |

| Lowered 7 | Se | ( La ) |

| 7 | Sol | Te (& Ta) |

| Raised 7 | Si | Ti |

Fixed do solfège

In Fixed do, each syllable always corresponds to the same pitch; when the music changes keys, each syllable continues to refer to the same sound (in the absolute sense) as it did before. This is analogous to the Romance-language system naming pitches after the solfège syllables, and is used in Romance and Slavic countries, among others, including Spanish-speaking countries.

From the Italian Renaissance, the debate over the superiority of instrumental music versus singing led Italian voice teachers to use Guido’s syllables for vocal technique rather than pitch discrimination. Hence, specific syllables were associated with fixed pitches. When the Paris Conservatoire was founded at the turn of the nineteenth century, its solfège textbooks adhered to the conventions of Italian solfeggio, solidifying the use of Fixed doh in Romance cultures[14]

In the major Romance and Slavic languages, the syllables Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, and Si are the ordinary names of the notes, in the same way that the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B are used to name notes in English. For native speakers of these languages, solfège is simply singing the names of the notes, omitting any modifiers such as "sharp" or "flat" to preserve the rhythm. This system is called fixed do and is used in Belgium, Brazil, Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Romania, Latin American countries and in French-speaking Canada as well as countries such as Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Israel where non-Romance languages are spoken. In the United States, the fixed-do system is taught at many conservatories and schools of music including The Juilliard School in New York City, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Cleveland Institute of Music in Cleveland, Ohio.

| Note name | Syllable | Pronunciation | Pitch class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Romance | Anglicized | Italian | ||

| C♭ | Do♭ | do | /doʊ/ | /dɔ/ | 11 |

| C | Do | 0 | |||

| C♯ | Do♯ | 1 | |||

| D♭ | Re♭ | re | /ɹeɪ/ | /rɛ/ | 1 |

| D | Re | 2 | |||

| D♯ | Re♯ | 3 | |||

| E♭ | Mi♭ | mi | /miː/ | /mi/ | 3 |

| E | Mi | 4 | |||

| E♯ | Mi♯ | 5 | |||

| F♭ | Fa♭ | fa | /fɑː/ | /fa/ | 4 |

| F | Fa | 5 | |||

| F♯ | Fa♯ | 6 | |||

| G♭ | Sol♭ | sol | /soʊl/ | /sɔl/ | 6 |

| G | Sol | 7 | |||

| G♯ | Sol♯ | 8 | |||

| A♭ | La♭ | la | /lɑː/ | /la/ | 8 |

| A | La | 9 | |||

| A♯ | La♯ | 10 | |||

| B♭ | Si♭ | si | /siː/ | /si/ | 10 |

| B | Si | 11 | |||

| B♯ | Si♯ | 0 | |||

In the fixed do system, shown above, accidentals do not affect the syllables used. For example, C, C♯, and C♭ (as well as C![]() and C

and C![]() , not shown above) are all sung with the syllable "do".

, not shown above) are all sung with the syllable "do".

Chromatic variants

Several chromatic fixed-do systems have also been devised to account for chromatic notes, and even for double-sharp and double-flat variants. The Yehnian system, being the first 24-EDO (i.e., quarter tone) solfège system, proposed even quartertonal syllables. While having no exceptions to its rules, it supports both si and ti users.

| Note name | Syllable | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Romance | Traditional [15] |

5 sharps, 5 flats [15][16][17] |

Hullah [18] |

Shearer [19] |

Siler [20] |

Latoni [21] |

Yehnian (chromatic)

(Si users / Ti users)[22] |

Pitch Class | |||

| C |

Do |

do | – | duf | daw | du | Ka | Dɚ | 10 | |||

| C♭ | Do♭ | – | du | de | do | Ne | Də | 11 | ||||

| C | Do | do | do | do | da | Bi | Do | 0 | ||||

| C♯ | Do♯ | di | da | di | de | Ro | Du | 1 | ||||

| C |

Do |

– | das | dai | di | Tu | Dü | 2 | ||||

| D |

Re |

re | – | raf | raw | ru | Be | Rɚ | 0 | |||

| D♭ | Re♭ | ra | ra | ra | ro | Ri | Rə | 1 | ||||

| D | Re | re | re | re | ra | To | Re | 2 | ||||

| D♯ | Re♯ | ri | ri | ri | re | Mu | Ru | 3 | ||||

| D |

Re |

– | ris | rai | ri | Ga | Rü | 4 | ||||

| E |

Mi |

mi | – | mef | maw | mu | Ti | Mɚ | 2 | |||

| E♭ | Mi♭ | me | me | me | mo | Mo | Mə | 3 | ||||

| E | Mi | mi | mi | mi | ma | Gu | Mi | 4 | ||||

| E♯ | Mi♯ | – | mis | mai | me | Sa | Mu | 5 | ||||

| E |

Mi |

– | mish | – | mi | Mü | Mi | 6 | ||||

| F |

Fa |

fa | – | fof | faw | fu | Mi | Fɚ | 3 | |||

| F♭ | Fa♭ | – | fo | fe | fo | Go | Fə | 4 | ||||

| F | Fa | fa | fa | fa | fa | Su | Fa | 5 | ||||

| F♯ | Fa♯ | fi | fe | fi | fe | Pa | Fu | 6 | ||||

| F |

Fa |

– | fes | fai | fi | Le | Fü | 7 | ||||

| G |

Sol |

sol | – | sulf | saw | su | So | Sɚl / Sɚ | 5 | |||

| G♭ | Sol♭ | se | sul | se | so | Pu | Səl / Sə | 6 | ||||

| G | Sol | sol | sol | so | sa | La | Sol | 7 | ||||

| G♯ | Sol♯ | si | sal | si | se | De | Sul / Su | 8 | ||||

| G |

Sol |

– | sals | sai | si | Fi | Sül / Sü | 9 | ||||

| A |

La |

la | – | lof | law | lu | Lu | Lɚ | 7 | |||

| A♭ | La♭ | le | lo | le | lo | Da | Lə | 8 | ||||

| A | La | la | la | la | la | Fe | La | 9 | ||||

| A♯ | La♯ | li | le | li | le | Lu | La | 10 | ||||

| A |

La |

– | les | lai | li | No | Lü | 11 | ||||

| B |

Si |

si | – | sef | taw | tu | Fa | Sɚ / Tɚ | 9 | |||

| B♭ | Si♭ | te | se | te | to | Ke | Sə / Tə | 10 | ||||

| B | Si | ti | si | ti | ta | Ni | Si / Ti | 11 | ||||

| B♯ | Si♯ | – | sis | tai | te | Bo | Su / Tu | 0 | ||||

| B |

Si |

– | sish | – | ti | Ru | Sü / Tü | 1 | ||||

| A dash ("–") means that the source(s) did not specify a syllable. | ||||||||||||

Note names

In the countries with fixed-do, these seven syllables (with "si" rather than "ti") – and not the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B – are used to name the notes of the C-Major scale. Here it would be said, for example, that Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (in D minor) is in "Re minor", and that its third movement (in B-flat major) is in "Si-bemol major".

In Germanic countries, on the other hand, the notes have letter names that are mainly the same as those used in English (so that Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is said to be in "d-Moll"), and solfège syllables are encountered only in sight-singing and ear training.

Cultural references

- The various possibilities to distinguish the notes acoustically, optically and by ways of speech and signs, made the solfège a possible syllabary for an International Auxiliary Language (IAL/LAI). This was, in the latter half of the 19th century, realised in the musical language Solresol.

- In The Sound of Music, the song "Do-Re-Mi" is built around solfège. Maria sings it with the von Trapp children to teach them to sing the major scale.

- Ernie Kovacs' television show had a popular recurring sketch that became known as "The Nairobi Trio". The three characters wore long overcoats, bowler hats, and gorilla masks, and were performed by Ernie and two other rotating persons including uncredited stars such as Frank Sinatra and Jack Lemmon, as well as Kovacs' wife, singer Edie Adams. There was no dialog, the three pantomimed to the song Solfeggio by Robert Maxwell and the lyrics of the song were made up solely of the solfeggio syllables themselves. The sketch was so popular, that the song was re-released as "Song of the Nairobi Trio".

See also

- Sargam – Note in the octave (Indian classical music)

- Key signature names and translations – Translation of musical keys

- Numbered musical notation – Musical notation system used in Asia since the 19th century

- Vocable – Meaningful sound uttered by people

References

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2nd Ed. (1998) [page needed]

- ^ "Solfeggio". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ "Solfège". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ "Solmization". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ "Sol-fa". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ Davies, Norman (1997), Europe, pp. 271–272

- ^ a b McNaught, W. G. (1893). "The History and Uses of the Sol-fa Syllables". Proceedings of the Musical Association. 19. London: Novello, Ewer and Co.: 35–51. doi:10.1093/jrma/19.1.35. ISSN 0958-8442.

- ^ Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalum (1680) OCLC 61900507

- ^ Essai sur la Musique Ancienne et Moderne (1780) OCLC 61970141

- ^ Farmer, Henry George (1988). Historical facts for the Arabian Musical Influence. Ayer Publishing. pp. 72–82. ISBN 0-405-08496-X. OCLC 220811631.

- ^ Miller, Samuel D. (Autumn 1973). "Guido d'Arezzo: Medieval Musician and Educator". Journal of Research in Music Education. 21 (3). MENC_ The National Association for Music Education: 239–245. doi:10.2307/3345093. JSTOR 3345093. S2CID 143833782.

- ^ Miller 1973, p. 244.

- ^ "Movable "Do" vs Fixed "Do"". Teaching Children Music. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Andrew (2 October 2024). "Identity, Relationships, and Function in Higher Music Education: Applying an Analogy from Ear Training to Student Wellbeing". International Journal of Music, Health, and Wellbeing. 2024 (Autumn): 4. doi:10.5281/zenodo.13882200.

- ^ a b c Demorest, Steven M. (2001). Building Choral Excellence: Teaching Sight-Singing in the Choral Rehearsal. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-512462-0.

- ^ Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; Nelson, Robert (2005). Music for Sight Singing (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thompson Schirmer. pp. x–xi. ISBN 978-0-534-62802-4.

- ^ White, John D. (2002). Guidelines for College Teaching of Music Theory (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8108-4129-1.

- ^ Hullah, John (1880). Hullah's Method of Teaching Singing (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. xi–xv. ISBN 0-86314-042-4.

- ^ Shearer, Aaron (1990). Learning the Classical Guitar, Part 2: Reading and Memorizing Music. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-87166-855-4.

- ^ Siler, H. (1956). "Toward an International Solfeggio". Journal of Research in Music Education. 4 (1): 40–43. doi:10.2307/3343838. JSTOR 3343838. S2CID 146618023.

- ^ Carl Eitz (1891). Das mathematisch-reine Tonsystem.

- ^

Yeh, Huai-Jan (12 February 2021). "Yehnian Solfège / 葉氏唱名 / Solfeggio Yehniano". Reno's Music Notes. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

... The Yehnian Solfège is an intuitive, easily adoptable, and professionally capable quartertonal solfège system ...